Sri Lanka

On the map, the island located off the southern shores of India looks like a drop. Reference books and travel guides also note that Ceylon resembles a drop of rain dropped by the monsoons of the Indian Ocean, but I have heard another interpretation — for many, its outlines are associated with the tears of a people who have borne 450 long and bitter years of humiliation and slavery on their shoulders.

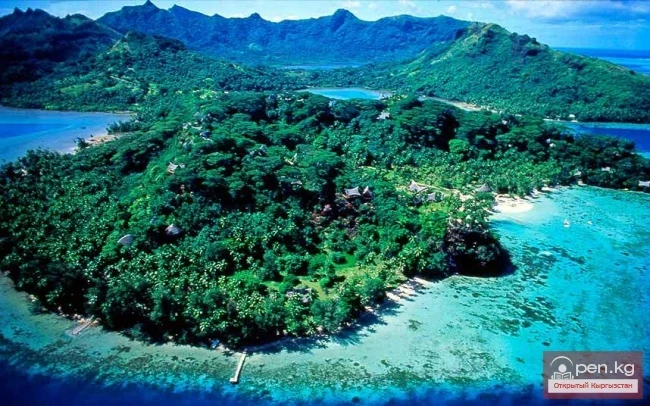

In brochures and booklets for tourists, the name of the island is invariably supplemented with colorful and flattering epithets: "earthly paradise," "promised land," "island of eternal tranquility," "pearl in the green necklace of the equator." Ceylon, or Lanka (as the locals call it), is indeed remarkably beautiful. Its shores are embraced by coconut groves like an emerald border, the crowns of palm trees are reflected in the blue waters of the lagoon, the mountain peaks are veiled in a bluish haze, and waterfalls cascade down from the heights of the clouds like white lace.

This is how the island appears to numerous tourists. But you will see it with different eyes if you spend a few years here.

Ceylon is rich: it ranks among the top producers of tea, rubber, and coconut products in the world. Its forests are home to ebony, teak, rosewood, satinwood, and silkwood. High-quality graphite deposits have been discovered on the island, and precious stones — topazes, rubies, moonstones, amethysts, alexandrites, and finally, the famous Ceylon sapphires — have been mined here since ancient times. It is no wonder that in ancient times it was called "Ratnadwipa" ("Island of Gems").

And yet, Ceylon is poor: it lacks its own industry. Annually, around one hundred thousand tons of natural rubber are harvested here, but no more than a thousand tons are processed in semi-handicraft factories. The state pays significant amounts in foreign currency for tires and tubes, which are often made from local rubber.

Colonizers, who dominated the island for several centuries, sought to place it in complete economic dependence on themselves. Even now, out of the sixteen largest banks in the country, fourteen are owned by financial trusts or financiers from foreign powers. More than forty percent of the land under tea plantations (including the best and most fertile) belongs to the English.

The results of the colonizers' activities are reflected in statistics — the annual income per capita here is approximately eleven times lower than in England. A Ceylonese consumes milk twelve times less, sugar ten times less, and fats five times less than an Englishman.

Contrary to the claims of travel guides for tourists, Ceylon has never been an "island of eternal tranquility." Almost all coastal cities have preserved Portuguese, Dutch, and English forts and fortresses, behind the walls of which foreign oppressors sheltered from the revolting islanders. In the central part of the country, not far from the city of Kandy, you can still be shown a place called "Red Sand." There, the fiercest battle once took place between heavily armed English punitive forces and freedom-loving Ceylonese.

After World War II, the powerful rise of the national liberation movement in Asian countries and the collapse of the entire colonial system of imperialism forced colonizers to grant independence to many of their colonies. Ceylon also received the status of an independent dominion within the British Commonwealth of Nations. On February 4, 1948 (this date is celebrated as a national holiday), the national flag depicting a lion holding a sword was solemnly raised over the country.

In the late 15th century, goods from Ceylon — pepper and cinnamon, peacock feathers and precious stones, gold, silver, and wooden products — were in great demand in the East. Merchants from many countries traded with the island. They called it by different names: Indians called it "Sinhaladwipa," Arabs called it "Serendib," and Greeks called it "Taprobane."

The West had heard of Ceylon's riches, but here they did not know where the "island of wonders" was located. Even F. D'Almeida — the Viceroy of Portuguese possessions in India — did not know, although the distance from India to Ceylon across the Palk Strait is less than a hundred kilometers. Indian merchants evidently knew how to keep their "trade" secrets.

It was not only the island's wealth that attracted the attention of the rulers of Western states, particularly Portugal, the most powerful maritime power of that time. Once the approximate coordinates of Ceylon became known, Europeans quickly understood the advantages of its location. There was no doubt that whoever seized the island would be able, with a sufficient fleet, to control all communications in the Indian Ocean.

The thought of conquering Ceylon seemed very tempting to the Portuguese King Manuel, and its implementation appeared to be an easy task. There was no need to outfit an expensive expedition: the natives, according to reports from informants, were poorly armed, and therefore D'Almeida would not require assistance from the metropolis.

Soon a special messenger delivered a royal decree to the Viceroy of Goa in India, proposing that he approach Ceylon, build a fortress there, and leave men and ships for its protection. However, it fell to not F. D'Almeida, but his son Lorenzo D'Almeida, a "gentleman of fortune," to carry out this order. One day he was sent by his father to intercept sailing ships carrying goods from Moorish traders from the Moluccas to the shores of the Persian Gulf. Usually, on the way, the sailing ships would stop at the Maldives to replenish their supplies of water and food. It was here that the Portuguese set an ambush for them.

This time, the prolonged monsoons carried the caravels away from the Maldives to somewhere else. The crews began to grumble. Instead of the promised loot, they faced the same old salt pork, moldy hardtack, stale water, and, worst of all, uncertainty.

But then the loud voice of the lookout announced: "I see land." Carefully maneuvering between the reefs, the fleet entered an unknown port. Sailing vessels were docked at the piers. Don Lorenzo D'Almeida stepped ashore. He was the first European to set foot on Ceylon. This happened on November 15, 1505.

Local traders met the uninvited guests rather cautiously. Following the advice of their overseas colleagues — Arab and Chinese merchants, who were also not too pleased with the arrival of the Portuguese — they, without entering into negotiations about possible trade relations, recommended that the newcomers go to Kotte. Today, the only reminder of this city is the name of one of the districts of Colombo. At that time, it was the capital of the most powerful and developed of the Ceylonese states — Kotte. Colombo, located nine kilometers from the capital, was merely a modest port with a few warehouses.

D'Almeida sent a messenger to the ruler of Kotte requesting an audience, while he began to instruct his subordinates. All sailors and soldiers were forbidden, under the threat of death, to offend the local population, and the gunners were ordered to fire a few "random" shots with cannonballs.

In the medieval Ceylonese chronicle "Rajavaliya," there is a text of a report to the ruler of the kingdom about the arrival of the Portuguese. It stated: "Here, in the harbor of Colombo, appeared people with white skin... They wear clothes and hats made of iron, eat stones, and drink blood... They give two or even three gold or silver coins for one fish or lemon. The roar of their cannon is louder than the thunderclaps in the mountains. Their cannons fire balls that shake stone fortresses...".

In Kotte, this report caused concern and led to the convening of the Grand Council. It was clear that the Portuguese would propose establishing trade relations. On one hand, this promised benefits: foreigners paid generously in gold and silver for fish and fruits, which were abundant on the island, so they would not spare money for the goods that had brought fame to Ceylon in many countries; on the other hand, the Europeans were too well armed.

What if the Sinhalese would hear the sound of Portuguese swords more often than the sound of gold?

The council met for several days, but no consensus was reached. Meanwhile, D'Almeida continued to send new messengers, and each time his requests for an audience became more insistent. The council agreed that they could not delay any longer.

The courtier had already left the palace in Kotte and was heading to Colombo to deliver the Portuguese an official invitation for a royal audience when a breathless messenger handed him an urgent order to return immediately. The ruler commanded the courtier... More than 450 years have passed since the Europeans landed in Ceylon, but even now, when the Sinhalese want to say that someone was led astray or deceived, they say: "He was led the same way as the Portuguese from Colombo to Kotte." The fact is that from Colombo to Kotte (only nine kilometers) they were led for three whole days.

During the audience, D'Almeida assured the Sinhalese that the Portuguese had no hostile intentions, that they only wanted to trade honestly with Ceylon and therefore requested permission to build several warehouses and a small fortress in Colombo to protect their goods from the Moors, whose treachery, they say, is known to the whole world.

The ruler of Kotte did not deliberate for long. He concluded an agreement with the Portuguese, hoping that their gold, and if necessary their weapons, would help him retain his throne and protect him from the claims of petty feudal lords and tribal chiefs who had long ceased to recognize his authority.

In 1517, a whole Portuguese fleet of nineteen ships approached Colombo under the command of Lopez-Suarez Alvarengo. Immediately, the construction of a factory and an earthen fortress began. At first, everything was calm. The Sinhalese were perhaps only disturbed by the fact that only armed soldiers, masters familiar with fortress construction, and Franciscan monks in black robes arrived; merchants and the promised goods were nowhere to be seen.

Doubts intensified when the Portuguese began to construct a fort in Colombo with deep moats, drawbridges, and steep stone walls, and not a "small" one, as had been agreed, but one of unprecedented size for the Sinhalese.

Some advisers to the ruler of Kotte tried to convince him of the need to put an end to the construction of the fort while it was not too late. However, other courtiers and tribal leaders, with whom Alvarengo had managed to establish "friendly relations," argued that the Portuguese were building the fortress not so much for their own safety as for the safety of the state.

While all these issues were being discussed, an impressive fort with high bastions, embrasures, and watchtowers, where sentries in shining armor and helmets were stationed, grew on the shore of the Indian Ocean.

Having established themselves on Ceylonese soil, the Portuguese ceased to play the role of peaceful traders and protectors of the ruler of Kotte. When their demands for free provision of food for the garrison of the fortress and goods for shipment to Portugal were not met, punitive detachments began to act. They burned villages, killed men, and raped women.

The people's indignation reached its peak, and soon a twenty-thousand-strong Sinhalese army besieged the fort in Colombo. The odds were unequal — cannons and muskets against spears and arrows, forged armor against woven shields. Yet the Portuguese had a hard time. The siege lasted more than five months. Only reinforcements that arrived from the Indian port of Kochi saved the besieged from destruction, and the fort from annihilation.

After the victory, the colonizers dictated the ruler of Kotte the terms of a servile agreement. From now on, the Sinhalese were obliged to harvest wild cinnamon and deliver it to the ships, as well as to clear jungles for cinnamon plantations.

Over time, the Portuguese built fortifications and stationed garrisons in many coastal cities of Ceylon, particularly in Galle — in the south, Jaffna — in the north, and Negombo — in the west of the country. To consolidate their dominance on the island, they resorted to the help of the church. Franciscan missionaries engaged in vigorous activities to convert the local population to Catholicism. Those who did not wish to convert to the Christian faith were baptized by force, guided by the principle: "Start with prayer; if it does not achieve its goal, let the sword decide."

The rule of foreigners, the spread of Catholicism, and the increase in the tax burden caused outrage among the people. The discontented were united by the ruler of the state of Sitawaka, Rajasinghe I. Not far from Colombo, near the village of Muleriyawa, he fought the Europeans and achieved a significant victory. In this battle, according to the chronicler, more than a hundred battle elephants participated, a thousand Portuguese perished; "blood flowed like water across the fields of Muleriyawa."

Then the king of Sitawaka captured Kotte and began the siege of Colombo, where the remnants of the Portuguese troops managed to reach. Using blackmail, bribery, slander, and intrigue, the colonizers incited feudal lords against Rajasinghe, and with their help, they defeated him. But the people rose against the foreign oppressors many more times.

The Portuguese held on to Ceylon for about 150 years, and during all this time they essentially controlled only the coastal areas. They only occasionally dared to undertake punitive expeditions into the interior of the country. They did not have enough strength to establish themselves in the central part of the island and conquer the large state of Kandy located there. After several unsuccessful attempts, they were forced to finally abandon this idea.

The rulers of Kandy played a significant role in expelling the Portuguese from Ceylon, but they made the same mistake that the king of Kotte had made at one time. Desperate to rid themselves of the Portuguese at any cost, they decided to rely on other Europeans.

In early 1602, the Dutch ship "Brebes" dropped anchor near the port city of Batticaloa on the eastern coast of Ceylon. The admiral Spilberg, who arrived on this ship, went ashore and made his way to Kandy. He could easily have become a prisoner of the Portuguese or their loyal Sinhalese soldiers, and the "Brebes," which stood alone at anchor, could have been the prey of sailors. However, failure to carry out the personal order of the Governor of Holland and Zealand, Prince Maurice of Nassau, threatened even greater troubles.

The king of Kandy, Vimala Dharma (Surya I), received Spilberg with honor. He expressed his readiness to conclude an agreement for joint military action against the Portuguese and granted permission to build a naval fortress near Trincomalee. The agreement also contained another clause granting the Dutch East India Company the right to export cinnamon and pepper from Ceylon freely. In fact, this was the main goal of the admiral's expedition.

Later, the Dutch managed to change the wording of this clause. It was no longer just about a right, but about an "exclusive and monopolistic right" to all trade with Ceylon. The conditions of the military alliance were also clarified — the Dutch would provide troops, and all military expenses would be paid by the Kandy state. For the merchants of the Dutch East India Company, conducting military operations now cost them virtually nothing. The foreign soldiers guarding the interests of the company on Ceylonese soil and fighting for it were essentially funded by the Kandy rulers. The latter imposed additional taxes on their subjects to cover military expenses, who now not only had to pay new taxes but also work on harvesting cinnamon bark or establishing pepper plantations.

Such advantageous terms of the agreement allowed the Dutch to begin the liquidation of Portuguese strongholds in Ceylon. By 1640, the troops of the East India Company had seized all Portuguese fortresses on the eastern coast of the island, besieged, and stormed Galle. In 1644, the same fate befell the naval fortress of Negombo.

In 1656, a twenty-thousand-strong Sinhalese army under the command of the Kandy king Rajasinghe II, acting in conjunction with Dutch troops, captured Colombo — the main stronghold of Portuguese forces in Ceylon; two years later, their last fortress Jaffna fell. Thus ended the Portuguese occupation of the island.

Even before the Portuguese were expelled from Ceylon, disagreements began between the Dutch and Rajasinghe II. Despite the agreement that the fortresses taken from the Portuguese would be handed over to the Kandy state, this condition, like many others, was ignored. Disagreements increasingly turned into armed clashes. The refusal of the Dutch to hand over the fort in Colombo, in which Sinhalese troops played a decisive role and suffered heavy losses during its capture, caused particularly deep resentment.

With the Portuguese rule in Ceylon over, the Dutch troops had no intention of leaving the country. On the contrary, having fortified themselves in the main coastal cities of the island, they began to advance inland, building fortresses and leaving garrisons along their route. Like the Portuguese, they demanded more and more privileges for themselves, reinforcing these demands with weapons. Now the East India Company was no longer satisfied with just exporting cinnamon and pepper. They needed labor and land for establishing areca palm plantations, the nuts of which were in high demand in Asian countries. They also attempted to establish plantations of new crops, particularly coffee. Coastal lagoons were turned into pools where sea water was evaporated to produce salt, bringing significant profits to the merchants of the East India Company.

Uprisings frequently broke out in the country, brutally suppressed by the colonizers. Holland, an ally of the Kandy kings in the fight against the Portuguese conquerors, embarked on a path of war against the Kandy state.

In 1763, a ten-thousand-strong army of Europeans advanced on Kandy. At the cost of significant losses, the Dutch managed to capture the city and hold it for almost nine months. However, the Sinhalese troops surrounded them in a tight ring, cutting them off from coastal fortifications. Medical supplies for the wounded and sick, ammunition for those still able to bear arms, and food for both were running out.

The Dutch command decided to return to Colombo. The journey was not easy. The sick and wounded hampered the movement of combat columns. Heavy cannons, rendered useless due to a lack of gunpowder, became a burden. In every gorge, at every crossing, an ambush awaited the retreating troops. In one of the battles that broke out on the way to Colombo, more than four hundred Dutch soldiers fell.

The costly campaign for the East India Company long dampened the colonizers' appetite for punitive expeditions. Military actions took on a stable character. The Dutch now felt relatively safe only behind fortress walls. But such a retreat did not suit the East India Company at all. They had to pay for the maintenance of troops out of their own pockets. Profits were falling — each campaign cost many soldiers' lives while bringing in very little.

Troops were needed, but Amsterdam needed them more than ever. Holland was almost continuously at war with Spain, France, and England. Literally every soldier counted.

In an attempt to hold on to the island at all costs, the company made concessions, concluding an unfavorable agreement for itself with the Kandy ruler in 1766. The Sinhalese could buy salt from the Dutch at the cheapest price in exchange for permission to harvest cinnamon on certain plantations as agreed. But this, of course, could not save the Dutch East India Company, and the Netherlands itself, weakened by prolonged wars, had no time for distant overseas possessions.

In the second half of the 18th century, the struggle between England and Holland for colonial, trade, and maritime dominance intensified. On August 23, 1795, English Colonel Stewart, commander of a landing party that landed near the city of Trincomalee on the eastern coast of Ceylon, ordered his gunners to open fire on the Dutch fort Frederick.

This marked the beginning of military actions by the English against the Dutch, the beginning of the struggle for the right to plunder the island's wealth and exploit its population. On August 26, the white flag flew over the fort, signifying the capitulation of the Dutch garrison. The losses of the English during the capture of the fort amounted to fifteen killed.

Less than a year later, on February 12, 1796, English troops under the command of the same Stewart captured the fortress of Negombo without a single shot. Three days later, Colombo was occupied. Almost simultaneously, Dutch fortresses in Galle, Kalutara, Matara, and Jaffna capitulated.

In 1802, Ceylon came under the protection of the English crown and became a colony of Great Britain. The metropolis began systematically extracting wealth from the enslaved country. The experience gained in India, a significant part of which had already been conquered and "mastered" by English colonizers by that time, proved useful. Officials arriving from there brought new laws and regulations to Ceylon, primarily affecting the tax system. Unlike the Portuguese and Dutch, who collected levies from the rulers of states or tribal chiefs (who in turn passed this burden onto their subjects), the English taxed the population directly. Old taxes were increased, and new ones were introduced — on every coconut palm, fruit trees, tobacco cultivation, fishing, salt extraction, and precious stones, and these taxes had to be paid in cash.

All power in Ceylon was concentrated in the hands of the English governor-general. At the local level, it was exercised by officials of the East India Company, who displaced elected representatives. They stripped the island's population bare, not forgetting to pocket part of the loot for themselves, encouraged bribery, disregarded the customs of the country, and humiliated the dignity of its inhabitants.

Even Harry Williams, the author of the book "Ceylon — the Pearl of the East," an Englishman who never tired of listing the "benefits" bestowed upon Ceylon by his compatriots, was forced to write: "The Sinhalese clearly understood that this new type of representative of the white race was the worst of those they had ever encountered."

In the initial period of their establishment in Ceylon, the English primarily controlled the coastal areas. The Kandy state, occupying the central part of the island, still retained its independence. Neither the Portuguese nor the Dutch managed to conquer it. For the English, however, the conquest of this state became the main task. They hoped either to eliminate the ruler of Kandy and, by dividing his lands, secure themselves forever from possible hostile actions, or to turn the king into a submissive executor of the governor-general's orders. In this case, the colonizers would act as the sole masters of the entire territory of the island. Moreover, they intended to expand and strengthen the port of Trincomalee, turning it into their main base in the East. To quickly and efficiently move troops and transfer military supplies, a short land route connecting Trincomalee with Colombo was needed. This shortest route passed through the territory of Kandy.

The English closely monitored the situation in this state, waiting for a convenient moment to attack it. One day, a messenger with a secret message arrived at the residence of Governor Norse. In it, one of the king of Kandy's close associates reported that he had prepared a conspiracy to overthrow the current ruler and suggested placing a man on the throne who would obediently carry out the orders of the governor-general.

This plan appealed to Norse, especially since there were not many hopes for success in the war with Kandy. The population would undoubtedly support the ruler and resist the invaders if they decided on open military action.

Norse appointed General McDowell as his personal representative, and he, accompanied by a strong detachment of troops, headed for Kandy. It seemed that everything was going well. McDowell's detachment arrived safely in the capital, and Norse only had to wait for a messenger with news of the successful execution of the conspiracy. But the arriving messenger brought completely unexpected news. The author of the secret message demanded the Kandy throne for the services rendered and asked for the help of "brave English troops." Accepting these conditions would mean war against the king of Kandy, which Norse did not want, and he ordered the immediate return of McDowell's detachment to Colombo.

The "cloak-and-dagger" diplomacy failed. Repeated attempts by the English governor to conclude a "peaceful, equal, and mutually beneficial treaty" with the Kandyans also yielded nothing.

Meanwhile, London insisted on active actions. The question was increasingly raised before Norse — how long would Kandy be recognized as having the right to act as a "state within a state"?

In January 1803, English troops moved towards Kandy and soon approached the capital. They were met by an empty city: all the inhabitants had left and taken refuge in the mountains. From there, they continuously launched raids, exterminating small groups of enemy soldiers. The colonial troops remained inactive, but their losses were increasing. The situation was complicated by supply difficulties.

In June 1803, the Kandyans began the assault on their own capital. Now the English had nothing to hope for. They had no choice but to break through to Colombo. However, very few managed to return: the Kandyans relentlessly pursued them.

They troubled the English garrisons in Matara, Puttalam, Jaffna, Batticaloa, and on September 6, they besieged Colombo. The English had to start peace negotiations.

The colonizers took a long time to recover from the blow dealt by the Kandy troops. Only in January 1815, having previously called up solid reinforcements from India, did they dare to embark on a new campaign against the Kandy state.

Scouts sent ahead of the army spread a proclamation from the governor-general, which hypocritically stated that the English considered it their duty to protect the population from the tyranny of the ruler. Peasants were promised land, tribal leaders — the preservation of all privileges, and the clergy — freedom of worship.

In February, the heavily armed invaders entered Kandy. The king was deposed and exiled to India along with all his male relatives. The representatives of the Kandy nobility were read the so-called Governance Act, by which Ceylon was proclaimed a part of the British Empire.

Thus, on March 2, 1815, the sovereign rights of the last stronghold of the independence of the Sinhalese people were transferred to the English crown.

In their economic policy in Ceylon, the colonizers followed the principle of developing only those sectors of the economy that were profitable for them and building only what was needed for them.

As soon as prices for cinnamon, the main export crop of Ceylon, fell on the world market and demand for coffee increased, local peasants were forced to cut down cinnamon trees and establish coffee plantations. English officers, missionaries, judges, clerks of all ranks, not to mention those in power, rushed to buy land, as prices for land plots were set at minimal — five shillings per acre.

Almost free labor, the favorable climate and soil, and favorable market conditions contributed to a rapid increase in the area under coffee plantations; by 1897, it reached 250 thousand acres.

In the 1990s, a disaster unexpectedly struck. In a short period of time, almost all coffee bushes on the island died from a plant disease. But a way out was found: a new crop — tea — replaced coffee. The development of tea cultivation here was even more rapid. If in 1873 tea plantations occupied only 280 acres, by 1947 they had reached 550 thousand.

At the end of the 19th century, rubber plantations began to emerge. The developing automobile industry at that time required tires, and the slopes of Ceylon's hills and highlands became covered with rubber trees.

Every pound of tea, rubber, and coconut oil was transformed by the shrewd English into pounds and shillings, carefully tucked away in the safes of banking magnates, and pennies, carelessly tossed into the hands of Ceylonese laborers. But even these pennies then returned to English merchants. Tea and rubber plantations left no room for rice cultivation — the staple food of the Ceylonese, which could only be purchased through English merchants. Clothing and footwear also had to be obtained from the same merchants, who sold off surplus goods at high prices.

To replenish their treasury, the colonizers imposed new and new taxes on the island's population. Tax officials seemed to compete with each other to see who could remember what else had not been taxed. Do Ceylonese love to wear jewelry? Introduce a tax on jewelry. Is it customary to build houses with verandas in cities? Introduce a tax on verandas.

The English take pride in building a wide network of roads in Ceylon; it would be more accurate to say "a wide network of military-strategic communications." (It is noteworthy that the first railway connected Colombo and Kandy, the capital of the state, which the English spent so much effort conquering). These communications were laid during the tenure of Governor Barnes, who cannot be denied knowledge of military affairs: he was an aide-de-camp to Wellington, who defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo. It is said that almost immediately upon arriving on the island, he said: "First — roads, second — roads, and third — roads." Barnes considered the construction of roads, which would allow troops to be quickly moved to "dangerous" zones, more important and profitable than building and maintaining fortresses for English garrisons. Plantation owners did not object to this either. After all, the "dangerous" areas primarily referred to plantation regions, where uprisings of workers often broke out. Moreover, goods from the plantations were delivered along the same roads to the port cities, from where they were exported from the country.

Only for themselves, for their own benefits did the colonizers build railways, seaports, airfields, banks, and fashionable hotels in Ceylon.

The English love to say that their rule was a "happy" time for the Ceylonese. The latter, according to English historians, harbor "gratitude and respect" for the English, who introduced them to "civilization." However, this "civilizing" mission actually brought the Ceylonese colonial order, enslavement, and national humiliation. Not a year went by without some part of the country witnessing uprisings against foreign occupiers. The memory of the uprisings of 1803, 1818, and 1848, when the entire population of the country rose as one against the invaders, still lives on among the people. These uprisings are hardly mentioned in English literature, and if they are mentioned, of course, nothing is said about how punitive detachments burned villages, trampled fields, destroyed reservoirs, and cut down coconut palms and fruit trees, condemning peaceful residents to starvation.

The colonizers did not "grant" Ceylon independence, as bourgeois politicians claim. They were forced to leave the island by the growing democratic and national liberation movement, the economic and political struggle of the working people. After World War II, a wave of strikes by dock workers, bank employees, and plantation workers swept across the country, and in 1947, under the leadership of the Communist Party of Ceylon, a general strike was held. The people's struggle was crowned with success — on February 4, 1948, Ceylon was proclaimed an independent state.

Read also:

Christmas Island

CHRISTMAS ISLAND Located in Oceania, in the southeastern part of the Indian Ocean, 2623 km...

Pitcairn

PITCAIRN A volcanic island in Oceania, in the southeastern part of the Pacific Ocean. This British...

"Closed" Islands Where Tourist Entry is Prohibited

Ten Islands Where Tourists Are Prohibited from Entering Despite all modern technological...

Aruba

ARUBA A territory of the Netherlands in the southern part of the Caribbean Sea, on the island of...

Saint Helena Island

SAINT HELENA ISLAND A British territory in the southern part of the Atlantic Ocean, located 1900...

Niue

NIUE An island in Oceania, in the central part of the Pacific Ocean. Area - 262.6 km²....

Norfolk

NORFOLK An island in Oceania, in the south-western part of the Pacific Ocean, located 1676 km...

The Smallest Inhabited Islands in the World

The Smallest Inhabited Islands An island is considered to be a piece of land surrounded by water...

Country Names and Their Origins. D-J

Dominican Republic — from Latin dies Dominica, "day of God" ("Sunday"). The...

Coconut (Keeling) Islands

COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS Located in the Indian Ocean, consisting of 2 atolls (27 small coral...

Countries of the World - Amazing Etymology

UZBEKISTAN. "Land of the Uzbeks." Possibly derived from the name of the Golden Horde...

Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

SRI LANKA. Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka A country located in South Asia on the...

Republic of Nauru

NAURU. Republic of Nauru A state in Oceania, located on the eponymous coral island in the...

Island of Tourism and Entertainment

We flew from Cebu to Boracay by plane. There was cloud cover, firstly. Secondly, the windows of...

Unusual Beaches of the World

The Most Exotic, Beautiful, and Unusual Beaches in the World When you hear the word beach, your...

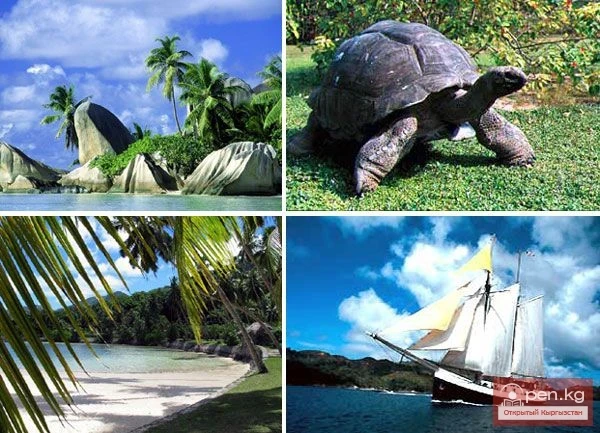

Republic of Seychelles

SEYCHELLES. Republic of Seychelles A state on the islands of the Seychelles archipelago (a total...

What the Names of the Countries of the World Mean. V-G

EAST TIMOR In Malay, "timur" means "east". The island is located at the...

What Do the Names of Some Countries Mean? N-R

Nauru — Pleasant Island On November 8, 1798, British captain John Fern landed on a remote island...

Guam

GUAM A U.S. territory in the western part of the Pacific Ocean on the island of the same name in...

Colombo — "Crossroads of Asia"

On a February evening in 1961, we took off from Sheremetyevo Airport on a "Super...

The State of Saint Lucia

SAINT LUCIA A state on the island of the same name in the group of Windward Islands of the Lesser...

The title translates to "The Entertaining Planet."

The clearest water is found in the Sargasso Sea (Atlantic Ocean). There are over 1300 types of...

What the Names of Countries Mean. L-M

Laos. From the ethnonym "Lao" — the most numerous people in the country. Lebanon. From...

56 Interesting Facts About Geography

56 Interesting Facts About Geography 1. The Kingdom of Tonga is the only monarchy in Oceania. 2....

Evergreen Plants of Kyrgyzstan: Juniper

Who hasn’t heard of juniper? Or cedar? Or cypress? Evergreens — in the literal sense of the word:...

Sary-Chelek Nature Reserve

The Sary-Chelek Nature Reserve is referred to as a realm of magical beauty, located on the...

Sarybulun Bead

Little Guest Such finds are not anticipated. They come from a fairy-tale land and are always...

Kyrgyzstan Included in the Top 10 Countries to Travel to in 2019 According to Lonely Planet Publishing

The authoritative international publisher Lonely Planet has included Kyrgyzstan in the list of the...

Irina Rashitovna Romanovskaya - on her love for nature and her passion for marine exoticism

While reading the science fiction novel by A. Belyaev, many dreamed of swimming with the amphibian...

Beautiful Places on Planet Earth

Amazing Places on the Planet There are various places in the world that differ in their natural...

Chocolate Hills

The airport in Manila is as crowded as an anthill. There are a huge number of flights. The...

Greenland

GREENLAND The largest island in the world. Located in the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans,...

Wallis and Futuna Islands

WALLIS AND FUTUNA (ISLANDS) An overseas territory of France, located in Oceania, in the central...

Arslanbob – the "Earthly Paradise" of Kyrgyzstan

Extensive areas of fruit and nut forests in the Arslanbob valley are the largest in the world. The...

From Chuvashia, 6.9 thousand tons of grain were exported in 2025, including a batch of flour to Kyrgyzstan.

- According to data as of October 22, since the beginning of 2025, employees of the...

Lake Köl-Suu

Lake Köl-Suu translates as "coming water" The lake is located in the Naryn region,...

Tokelau Islands

TOKELAU Islands in Oceania, in the center, part of the Pacific Ocean (atolls - Atafu, Nukunono,...

Etymology of State Names

SAUDI ARABIA . The kingdom was formed within its current borders in 1926. The name was adopted in...

Balancing Stones and Rocks

A balancing stone is a natural geological formation where a large stone, sometimes of enormous...

Rice Terraces of Banaue

It is very hot and stuffy on the plane, and outside the window, it is deep night. We are flying...

The Origin of the Names of the Countries of the World. K-K

Kazakhstan. “Land of the Kazakhs.” From the name of the people, which, according to one version,...

The Scariest Places on Earth

The Creepiest Places in the World Despite the fact that abandoned cities and eerie corners of the...

The Least Explored Places on Earth

The Most Unexplored Places on Our Planet Climate and human factors constantly affect the Earth. It...

Several Interesting Facts About Planet Earth

Unique Planet Earth Planet Earth is just one of eight (according to the latest data) planets in...

Express Facts about Earth

Air pollution in China is so severe that it can be seen from space. A cubic meter of the...