The State of Timur's Emirate

Foundation of the Great State. In the 1370s, a powerful state was established in Central Asia under the rule of Emir (Ruler) Timur.

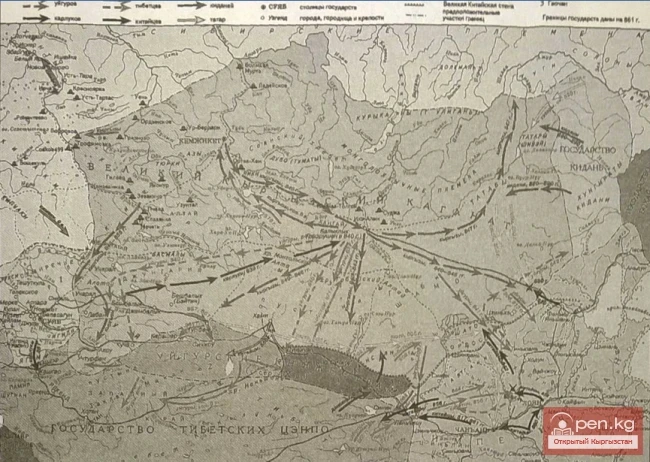

Aiming for world domination, Timur gathered a strong army and conquered neighboring countries one after another. By the end of the 14th century, Emir Timur had annexed the main territories of Central Asia and waged a relentless war to conquer Afghanistan, Iran, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, and the Volga region.

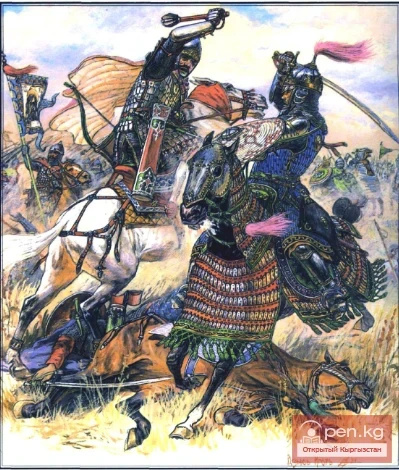

Through Semirechye, he conducted raids into Moghulistan. The armies of Emir Timur invaded the lands of the Kyrgyz multiple times—in 1370-1371, 1375, 1377, and 1389. The last time they reached the Irtysh River. The armies of the Kyrgyz tribes, united in the face of a formidable enemy, were defeated in battle against Timur's numerous forces in the interfluve of the Ili and Irtysh rivers.

The strengthening of Emir Timur's dominance prompted the rulers of neighboring states in the 1380s to unite in a single alliance to resist the invasion of the enemy. This alliance included the Khan of the White Horde Tokhtamysh, the ruler of Kashgar, the Mongol Khan Khizr-Khodja, the ruler of the Mongols Kamar ad-Din, and the leader of the Kyrgyz Baymurat-toro.

In 1387-1388, taking advantage of the fact that Timur's forces were directed to Iran, the allies invaded Mawarannahr and plundered and destroyed some areas of the emir's possessions. However, their attempts to seize the economic and political centers—the cities of Samarkand, Bukhara, and Urgench—were unsuccessful.

Timur's Campaigns Against the Kyrgyz. After returning from the Iranian campaign, Timur unexpectedly attacked Moghulistan in 1389. Khan Tokhtamysh, who had the strongest army, did not assist his allies. The Mongols were unable to timely join forces with the Kyrgyz. The main blow of Timur's numerous army fell on the Kyrgyz forces led by Baymurat. A bloody battle between the opponents took place at the foot of the Tarbagatai Mountains in the valley of the Kobuk River. The undeniable superiority of Timur's troops determined the outcome of the battle: the Kyrgyz were forced to retreat to the other bank of the Irtysh.

Another part of the Kyrgyz army, primarily composed of the Bulghachi tribe, fought against Timur's forces twice: the first time in the Beykut area in eastern Pre-Tianshan, and the second time in the Chichkan-Daban area. The first battle was particularly bloody. According to sources, "the fire of that battle raged for a whole day." Again, the Kyrgyz, not receiving timely reinforcements from their allies, suffered defeat. The surviving Kyrgyz were ordered by Timur to be resettled to Andijan, Fergana, and Pamir-Alai.

After defeating the Kyrgyz, Timur's army moved towards the Mongol Khanate. In the Turfan region of Eastern Turkestan, the troops of Omar-Sheikh, Timur's son, defeated the forces of Khizr-Khodja.

As a result of these conquests, Kyrgyzstan became part of Timur's vast empire. Northern Kyrgyzstan, given by Timur to his grandson Ulugh Beg, was governed through his viceroy in Tashkent. Southern Kyrgyzstan passed to Timur's other grandson—Iskander—and was governed through the viceroy of Fergana.

Timur's military campaigns in Moghulistan and other states led to the death and devastation of thousands of people. The conquerors stole the livestock of the Kyrgyz, for whom war was a means of enrichment.

The state created as a result of the conquest wars began to disintegrate after Timur's death, as economic and political ties were not established between its numerous possessions. The ongoing feudal infighting during the reign of Timur's descendants accelerated this process. After Timur's death, Moghulistan and Kyrgyzstan regained independence. The Timurids continued the policy of subjugating Moghulistan but were unable to consolidate their power.

Timur's Supreme Council. The golden tent of Emir Timur shines. In the center of the tent rises a golden throne, turned southwest. The Supreme Council is convened. Around the throne, in a semicircle, sit his sons, grandsons, and brothers according to age and rank. To the right of the throne sit the relatives of the godlike emir—sayyids, judges, theologians, elders, and noble dignitaries. To the left sit the supreme commander (military minister), khans, akims (rulers of possessions), tumenbashi (commanders of ten thousand warriors), thousand commanders, and hundred commanders. Opposite the throne sits the head of the Supreme Council (divan), viziers, and behind them, in the second row, seats for lower-ranking dignitaries. Behind the throne, on the right side, are the commanders of the light cavalry units.

The sound of drums is heard. To the sounds of the zurna, four enormous slaves bring in a litter and lower it before the throne. Timur slowly rises from the litter and approaches the throne. Before sitting down, he raises his right hand, greeting all those gathered. At that moment, the commander of the vanguard forces takes a seat opposite the throne, and on both sides of the entrance to the tent are the commanders of the personal guard.

Such a Council is always held before the start of a new campaign or in honor of a significant victory. They all proceeded in the same way. Emir Timur congratulated everyone on the victory, noted and rewarded those who distinguished themselves, conferred titles, and distributed possessions, and resolved current matters. The ceremony of the Supreme Council concluded with a lavish feast.

Another governing body of Timur was the Small Council. It included only sons, grandsons, relatives, viziers, emirs, tumenbashi, and thousand commanders. The meetings of the divan also ended with a meal. Those local rulers, emirs, and military leaders who did not participate in the council but were in the camp were given "gifts": they were sent food from the table.

Those close to Timur, whom he lost trust in, were initially removed from participation in campaigns and then not invited to his camp or to council meetings.

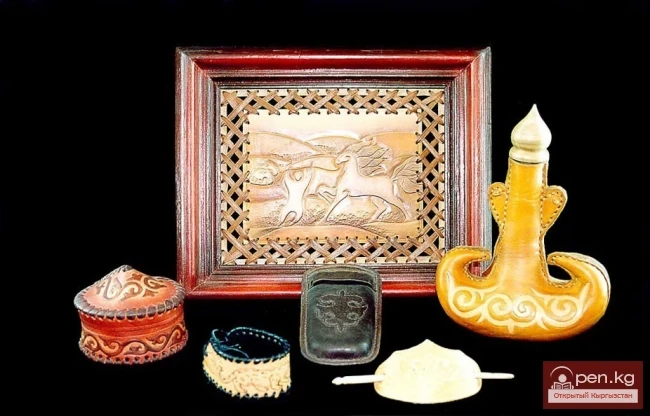

Timur was particularly attentive to his own appearance and comforts. Perhaps, for him, the clothing and adornments of the conquered peoples served as a reminder of victories and an opportunity to remind others of his greatness. Emir Timur always wore a wide long silk robe. If in the robe he resembled a Chinese emperor, then in a pointed cap adorned with rubies, emeralds, and other precious stones, he looked like a mountaineer, and with massive earrings studded with gems, he resembled a Mongol. Despite having embraced Islam and keeping sayyids, sheikhs, and spiritual advisors, he did not wear a turban.

Such splendor also reigned in the camp. Clothing was made from silk, velvet, and satin. Some details reflected Arab style, but it was mainly characteristic of nomads.

Viziers, emirs, and other noble dignitaries demonstrated their status through the elegance and luxury of their attire: they preferred rich clothing, belts decorated with embossing and precious stones, and wore sabers and daggers made by renowned master craftsmen. Women wore high conical headdresses—shokulye—and long silk dresses. The collar and front of the dress up to the waist were adorned with embroidery, while the back hem was longer. Such dresses were worn in ancient times by the queens of the Saka, Iranians, and Khwarezmians. Women covered their faces with silk veils. Maids wore dresses with ruffles and long trousers.

Read also:

Khizr-Khodja Khan of Moghulistan

The Rule of Khizr-Khodja in Moghulistan There is no data in written sources about when...

The Campaigns of Timur 1383-1389.

Timur's Campaigns In 785/1383-84, Timur sent Emir-zade Ali with an army to search for Kamar...

The Fourth Campaign of Timur to Moghulistan Due to the Invasion of Kamar ad-Din in Fergana

Timur's Campaign to Moghulistan In 1376, before the campaign to Khwarezm, Timur sent an army...

The Campaigns of Timur in Moghulistan in 1370-1375.

Campaigns in Moghulistan in 1370-1375 Nizam ad-Din Shami reported on the raids of the Mongol emirs...

The First Khans of Moghulistan. Ilyas-Khodja

Ilyas-Khodja In 764/1362—63, the emirs Shiraman, Khodja, Tunam, Kamar ad-Din, Shams ad-Din, and...

Timur's Victories in Moghulistan

Moghulistan Under the Raids of Timur's Troops After a halt in Kara-Guchur, Timur sent 30,000...

The Ruler of Fergana Iskander, Grandson of Timur

Campaigns of Iskander Khyzr-Khodja died in 1399, and immediately after his death, a struggle for...

Mogulistan in 1407 - 1417 Years

Mogulistan in the First Quarter of the 15th Century As already noted, after the death of...

The State of Tugluk-Timur or Moghulistan

Division of the Descendants of Genghis Khan into Two Warring Factions Abd ar-Razzaq al-Samarqandi,...

Zahir al-Din Muhammad Babur (Zahiruddin Babur)

The Timurid ruler and scholar - Zahir ad-Din Muhammad Babur (1483-1530), was the founder of the...

Bekchik (bikchik) — a Turkic tribe

Lake Bekchiks Bekchik (bikchik) — a Turkic tribe. V. P. Yudin and K. A. Pishulina identify them...

Itardji, Yarki, Kaluchi

Itardji, Yarki, Kaluchi Itardji (Itarchi) have been known since the time of Khizr-Khodja-khan....

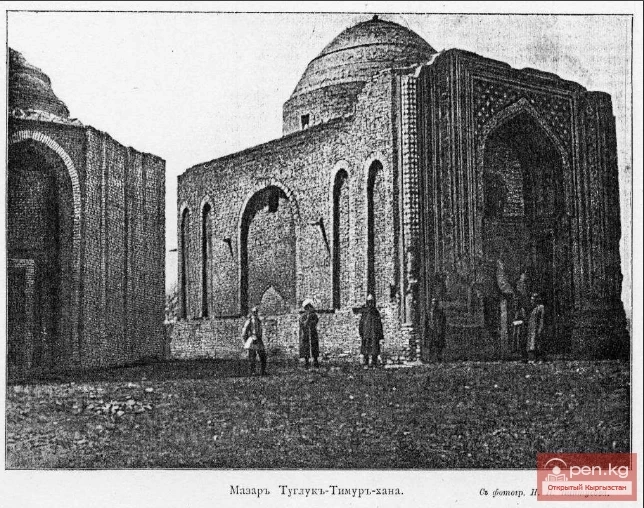

The First Khans of Moghulistan. Toghluk-Timur

The First Khans of Moghulistan After the assassination of Khan Kazan in the eastern part of the...

The Territory of the Kyrgyz in the VI—XVIII Centuries

All political entities of the Middle Ages in the territory of Central Asia somehow affected the...

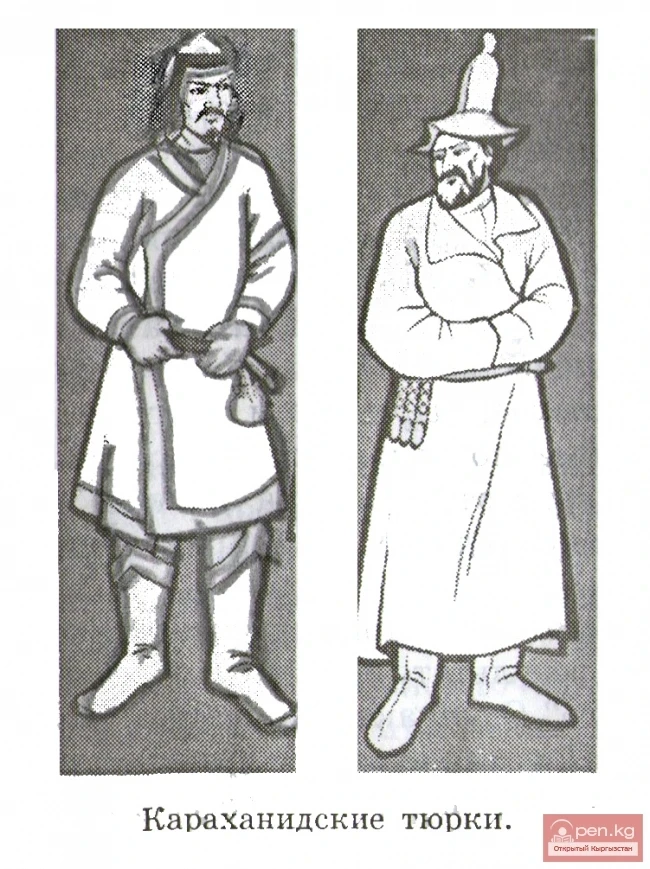

The State of the Karakhanids (940—1212)

Karakhanid State (940—1212 years). From the mid-10th century to the early 13th century, the Turkic...

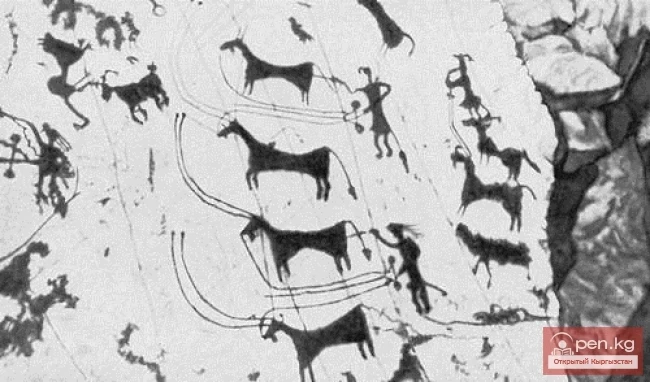

Military Forces of the Kyrgyz from Ancient Times to the 6th Century

The military art that prevailed during the ancient and medieval periods among the nomadic tribes...

The title translates to "Khoja Ahmed Yasawi."

The 12th century is associated with the name of the steppe poet, thinker, and major representative...

Protoichiliks, a part of the Kyrgyz people

Muhammad Haider refers to the Kyrgyz as "the forest (wild) lions of Moghulistan." It is...

Foreign Policy of the Kyrgyz in the 18th - Early 20th Century

During the period in question, Kyrgyzstan was unable to conduct any foreign policy. However,...

Ulugh Beg Muhammad Taragay

Southern Kyrgyzstan was fully integrated into the world of science and culture during the Timurid...

The Reign of Esen-Buka

The Ascension of Esen-Buka to the Throne In 1309, at the initiative of Kebek, a kurultai was...

Muhammad Kyrgyz

The situation in Central Asia. In the early 16th century, feudal fragmentation intensified not...

Esin-Buka and Other Emirs

Esan-Buka Esan-Buka, his ulusbek (Seiid Ali), and his court continued to pursue the supporters of...

Inclusion of Eastern Tianshan into the State of Haidu

Kublai's Struggle Against Haidu The uprising of Shireki and Tuk-Timur is also mentioned in...

Eastern Turkestan in the 17th Century

Eastern Turkestan in the 17th Century. At the end of Muhammad Khan's reign, his younger...

Military Forces of the Kyrgyz in the 6th to 18th Centuries

The structure, organization, and supply of the armed forces of the Kyrgyz during that period were...

Osh. In the Composition of Moghulistan

In the early 15th century, Osh is mentioned in eastern chronicles in connection with the campaign...

Popular Movements in Central Asia in the 19th Century

The Kyrgyz people, defending their freedom and land, alongside other peoples of Eastern Tian Shan...

Battles for Eastern Turkestan

Stories of Rashid ad-Din In 1275, Duva and Busma surrounded the city of Kara-Khodja, near Turfan,...

The Geopolitical Environment of the Kyrgyz Before the 6th Century

Since the Sakas did not have a centralized state, they did not conduct a specific foreign policy....

The Beginning of Haidu's Political Career

Haidu Jemal Karshi met with Haidu twice and received valuable gifts from him. The author speaks of...

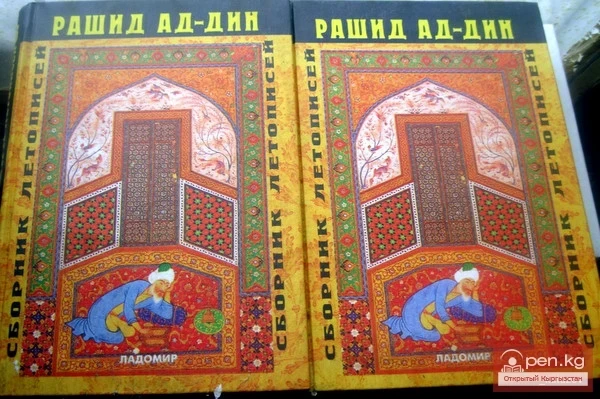

The Collection of Chronicles of Rashid ad-Din

Rashid ad-Din. Collection of Chronicles. Vol. I. M.-L., 1952 Rashid ad-Din (1247—1318) was the...

Ancient Kyrgyz — the Earliest West Turkic Tribes

Ancient People — Kyrgyz The Kyrgyz, whose roots go deep into antiquity, lost in the darkness of...

Kyrgyz Khaganate: The Leading Nomadic State in Central Asia from the Mid-9th to the First Quarter of the 10th Century

Kyrgyz Great Power During the VI-VIII centuries, when the Kyrgyz state existed only in the...

How the Kyrgyz Entered the Kokand Khanate

The Birth and Change of Dynasties of the Future Alay Queen Before delving into the era in which...

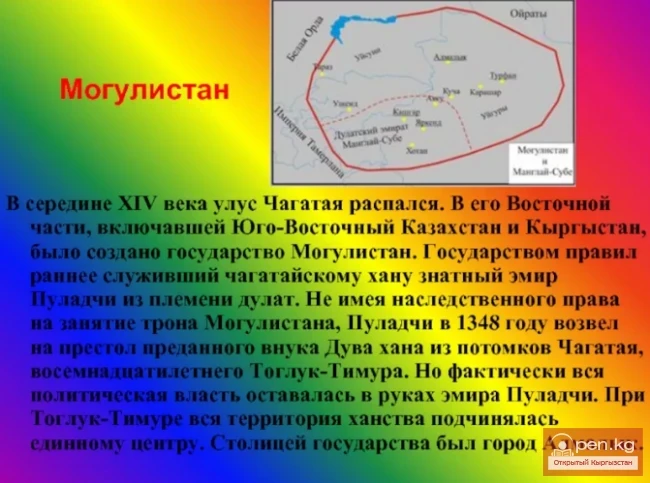

The Formation of the State of Moghulistan

THE STATE OF MOGULISTAN Since the formation of the empire of Genghis Khan, his descendants—the...

The Role of the Moghulistan State in the Formation of the Kyrgyz People

Formation of the Kyrgyz People The Kyrgyz people were formed on the basis of two ethnic masses:...

Valuable Sources on the History of the Kyrgyz in the 16th-17th Centuries. Part - 6

Works of Medieval Authors The work "Shajaray-i Turk va Mogul" ("Genealogy of the...

Kyrgyz of the 19th Century in the Sketches of a British Traveler

Writer Thomas Witlam Atkinson traveled through Central Asia in the mid-19th century. Throughout...

Population of Mogulistan

Arkanuts, Arlats, Barlasses The problem being studied is one of the complex and poorly researched...

Ethnic Origins and Stages of Formation of the Kyrgyz Nationality

The formation of the Kyrgyz people is connected with ethnic processes in ancient and medieval...

This is Our Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan is a beautiful country! The video was created by Antares Creative Group on behalf of...

The First Kurultai in Central Asia "on the Meadows of Talas and Kendzhik"

Kurultai under the Leadership of Haidu. According to Rashid al-Din, in the spring of 1269, the...

Ethnopolitical Connections of the Altai Kyrgyz in the 13th to 15th Centuries

Movement of the Altai Kyrgyz to the Western Regions of Mogolistan In the study of the...

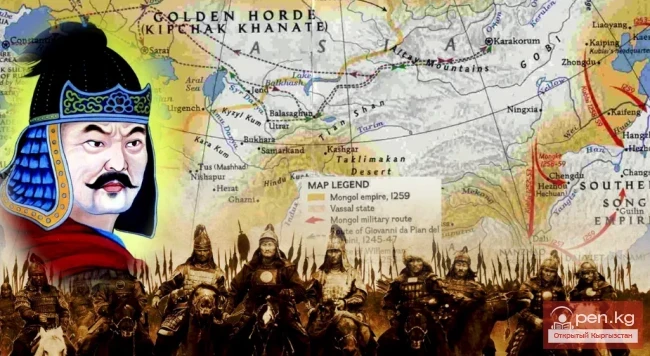

The Conquest Campaigns of Genghis Khan

The First Conquests of Genghis Khan. In the 12th and 13th centuries, on the vast territory of...

The State Structure of Mogulistan

State Structure In written sources, the state of Mogulistan or its regions, occupied by tribes and...