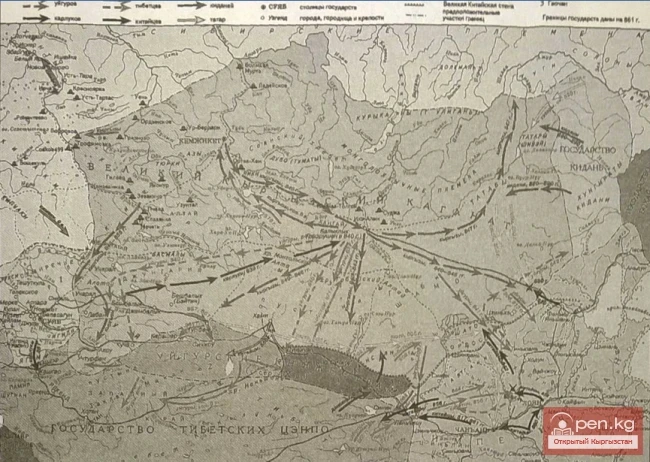

Movement of the Altai Kyrgyz to the Western Regions of Mogolistan

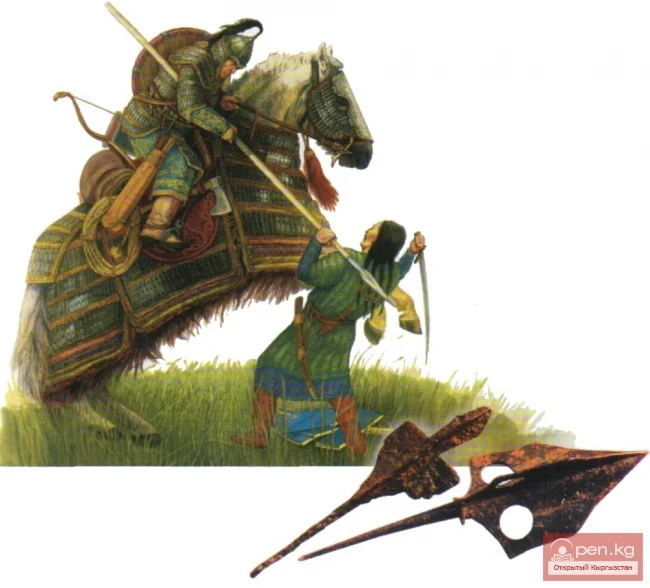

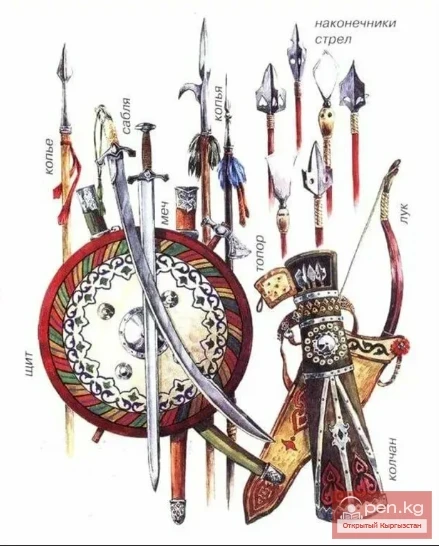

In the study of the ethnopolitical history of Southern Siberia at the beginning of the 13th century, an important place is occupied by the question of the conquest of the Kyrgyz and the forest peoples of Southern Siberia by Genghis Khan. However, the issues of the relationship between the Mongols and the Kyrgyz during this period remain insufficiently developed in the scientific literature due to the fragmentary and contradictory nature of the sources. The study of this issue is still based only on information from the "Secret History," Rashid al-Din's "Jami'at al-Tawarikh," and "Yuan Shi" (Bartold, 1963. Pp. 505-508; Kyzlasov, 1969. Pp. 131-138; Khudyakov, 1986. Pp. 72—75). As recently discovered reports from "Muqaddimah-i Zafar-name" show, contrary to the established position in historical science regarding the peaceful nature of the Kyrgyz's submission to Genghis Khan, the Kyrgyz princes (inal) were forced to express submission only as a result of a bloody battle when they realized that their forces were clearly insufficient to repel the Mongols (Mokeev, 2010. Pp. 85-90; Muqaddimah-i Zafar-name. Pp. 393. L. 27b-47a). According to another report from "Muqaddimah-i Zafar-name," the Altai Kyrgyz revolted against the Mongol yoke during the Mongol troops' campaign against the Khwarezm Shahs in the autumn of 1219. Genghis Khan was forced to send a punitive detachment to suppress it, as it could spread to other regions of Southern Siberia (Mokeev, 2010. Pp. 82-91). Thus, unlike the rulers of the Uyghurs, Karluks, and other vassals of Genghis Khan, the Kyrgyz military leaders did not actively participate in the Mongol troops' campaign to Central Asia in 1219, for which they were severely punished by the troops of Juchi, Genghis Khan's eldest son.

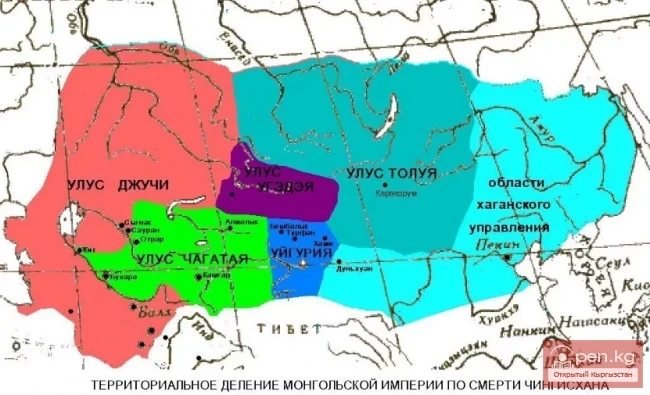

The Kyrgyz represented a serious threat to the security of the Yuan dynasty on the northern and northwestern borders of the empire. As a result of punitive operations by the troops of Khan Kublai, the Yenisei and Altai Kyrgyz were divided and dispersed by relocating them to the northeastern regions of Mongolia, China, and Manchuria (Kychanov, 2003. Pp. 237-240). It is evident that these groups were subsequently assimilated by the numerically predominant local population of these regions and merged into the Mongolian and Chinese peoples. The hostile policy of the Yuan dynasty towards the Altai Kyrgyz forced them to orient themselves towards the state of Haidu, and after its collapse in the first half of the 14th century, towards the state of Mogolistan.

After the conquest of the Kyrgyz by the Mongols, not only did the status of their principalities change, but the state-administrative system was also transformed in accordance with the military-political interests of Genghis Khan's state. During military campaigns in the land of the Kyrgyz, as well as through forced deportations of their most rebellious part, the Mongols completely exterminated the political elite of the Yenisei and Altai Kyrgyz - the inals, who were the bearers of the ancient tradition of statehood.

One of the main directions of the ethnic and political relations of the Altai Kyrgyz in the 14th-15th centuries was their relationship with the Oirat. The state union of the Oirat first appeared on the political scene of Southern Siberia after the fall of the Yuan Empire in the second half of the 14th century (Sanchirov, 2005. Pp. 158-189). It represented a conglomerate of Mongolic and Turkic-speaking tribes of the Sayan-Altai region and initially consisted of four tribes, which in Mongolian were called "dorben oy-rat" (four Oirat).

Among the first four tribes that created the Oirat state were the Kyrgyz (The Mongol Chronicle... 1955. P. 161; Pelliot, 1960. P. 6. Note 66; Beyshenaliev, 2001. Pp. 22-25).

By the end of the 14th century, power over this union of four Oirat tribes was in the hands of Ugechi-kashka from the Kyrgyz tribe, who in 1399, after killing the heir of the Mongol khans Elbek, subordinated not only the Oirat but also a significant part of the Mongols and began to rule as a sovereign ruler in the city of Karakorum (Documents. 1969. P. 185; Beyshenaliev, 1991. Pp. 78-84). During this period, the ancient title of the Kyrgyz rulers of the Sayan-Altai highlands from the time of Genghis Khan, inals, completely disappeared. The ruler of the Kyrgyz of Altai within the Oirat union acquired a new title - kashka. This indicates the complete extermination of the previous elite - direct descendants of the khans from the era of "Kyrgyz great power" by the Mongols in the 13th century.

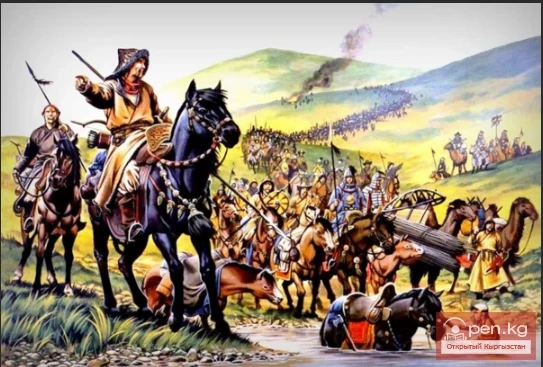

Even before the mid-15th century, the Altai Kyrgyz actively participated in the internal political events of the Oirat union. In particular, during the fierce struggle for power over the Oirat union between Esen-taishi and Akbarchi in 1451-1452, the Kyrgyz supported Akbarchi. However, after Akbarchi's defeat, Esen-taishi subjected all his supporters, including the Kyrgyz, to severe persecution. It was then that the process of resettlement of the Altai Kyrgyz in a western direction began, but according to some scholars, the final resettlement of the Altai Kyrgyz to the Tian Shan occurred 20 years later, during the mass invasion of the Oirat into Mogolistan in 1470-1473 (Akmedov, 1961. P. 33).

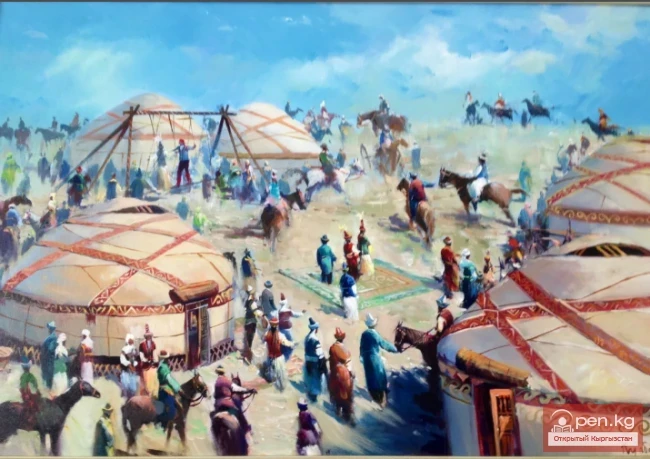

As noted above, a significant part of the Altai Kyrgyz avoided deportation and remained in their former territory under the rule of Haidu. In the mid-14th century, all northeastern possessions of the Haidu state, including the lands of the Altai Kyrgyz, became part of Mogolistan. The Kyrgyz of Mogolistan were referred to by Muslim authors of the 14th-15th centuries predominantly by the general political names "Mogols" or "Chagatai," which greatly complicates the study of their ethnic history. The unification of Mogolistan under the power of the Chagatai khans and the transformation of the cities of Eastern Turkestan into administrative, trade, and political centers of the country contributed to the development of economic, political, and cultural ties between individual Mongolian tribes. Under these conditions, a process of forming a new ethnic community based on local Turkic-speaking tribes was underway in the territory of this state (Yudin, 1965. P. 61).

However, due to the significant remoteness of the Kyrgyz tribes from the center of the state, their integration processes with the Mongolian tribes proceeded very slowly. Moreover, the consolidation of all tribes of Mogolistan was hindered in the second half of the 14th - early 15th centuries by the devastating, continuous campaigns of Timur and the Timurids, and the resulting exacerbation of internecine feudal struggles weakened the political unity of the state.

All this led to the departure of many Mongolian tribes to the Dasht-i Qipchaq, Mawarannahr, Khorasan, and even Mongolia.

Thus, there was a regrouping of the Mongols. Formerly powerful tribes (Dughlats, Arkenuts, Kangly, Bekchik, etc.) lost their former significance, while some previously secondary tribal unions rose to prominence. It is during this period that the strengthening of Kyrgyz tribal unions occurred, around which part of the Mongolian tribes began to consolidate. With the growth of influence within the country, the foreign political activities of the rulers of the Kyrgyz tribes of Altai and Priirtysh intensified. Sources contain information about military conflicts between the Kyrgyz and the Ak-Orda state in the early 15th century.

Therefore, at this time, the Altai Kyrgyz were close neighbors of the Ak-Orda state in the Priirtysh region (Muin ad-Din Natanzi. 1957. P. 89; Mahmud ibn Wali. FV 337. L. 27a, 286). A wide range of materials indicates the ethnic, political, and cultural similarities between the populations of Southwestern Altai and Eastern Dasht-i Qipchaq during this period (Potapov, 1953. P. 151).

Some sources mention Kyrgyz tribes living in the northeastern regions of Mogolistan: in the upper reaches of the Irtysh and in Southwestern Altai. In "Majmu'at al-Tawarikh," these areas are referred to as Shamal-i Jete (northern Mogolistan), and its population is called Altai-Mogol, i.e., Altai Mogols (Majmu'at al-Tawarikh. 1960. L. 51 ob).

Thus, in the 14th-15th centuries, a significant part of the Altai Kyrgyz lived in Mogolistan, inhabiting the least accessible mountainous and forested areas of this state (Tarikh-i Rashidi. No. 1430. L. 105a).

It is evident that the Altai Kyrgyz, under pressure from the Oirat, began to move to the southern and western regions of Mogolistan as early as the first half of the 15th century.

Before that, the peripheral Kyrgyz tribes preserved their strength during the invasion of Timur and the Timurids and now occupied the central regions of Mogolistan. After the weakening of the Dughlats and other Mongolian tribes, the Kyrgyz had the opportunity to occupy the rich pasture lands of the mountainous and forested areas of Semirechye and Tian Shan.

Probably, one of the main reasons for the resettlement of the Kyrgyz to Tian Shan can be considered the desire of their rulers to establish strong contacts with the settled agricultural population of Eastern Turkestan and Central Asia to ensure a constant influx of necessary products and goods, primarily grain, fabrics, and luxury items. This opportunity arose in the second half of the 15th century when Mogolistan fell into final disarray during intertribal and internecine wars, as well as devastating invasions by the Dzungar Kalmyks (Tarikh-i Abu-l-Khayr-khan. P. 478. L. 237a-239a; Tarikh-i Rashidi. V 648. L. 486). It was then that the majority of Kyrgyz tribes finally left Altai and Priirtysh for the rich pastures of Central Tian Shan, from where they could control a significant part of the Great Silk Road.

Common Origin of the Ancestors of the Modern Kyrgyz People and the Ancient Kyrgyz of Yenisei and Altai