Ethnocultural Connections Between the Kyrgyz and the Kipchaks

The significance and political role of the Yenisei Kyrgyz in the formation of a new ethnic community in Altai and the Irtysh region are reflected in "Ta-bai al-hayavan" by al-Marwazi (12th century), "Nuzhat al-mushtak" by al-Idrisi (12th century), and "Behjat at-tavarikh" by Shukrallah (15th century). According to the information from these sources, the rite of cremation, initially characteristic only of the Yenisei Kyrgyz, began to spread among the Kimak-Kipchak and other Turkic-speaking tribes of Altai and the Irtysh region after they established their political dominance over these tribes (Minorsky, 1942. P. 32, 108, 109; Kumekov, 1972. P. 109; Behjat at-tavarikh. P. 785. L. 29b-30a).

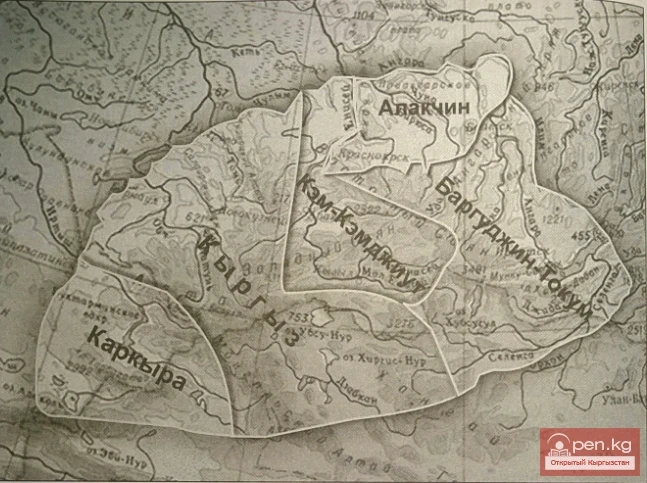

The ethnocultural connections between the Kyrgyz and the Kipchaks influenced the formation of the eastern Kazakhstan variant of the material culture of the Kyrgyz. Geographically, it is limited to the Upper Irtysh region, and to the south, it reaches the Dzungar Alatau, as indicated by the accompanying inventory items from burials near the city of Tekeli (Savinov, 1984. P. 93, 94). The materials from the burial mounds of the Zevakino necropolis, with cremation burials, testify to the interaction of local Kimak and incoming Kyrgyz tribes, which occupied a dominant position here (Archaeological monuments. 1987. P. 243-246).

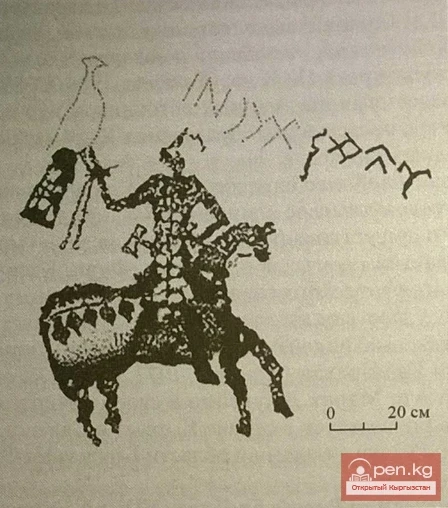

Research by Siberian archaeologists of several burial grounds in Southwestern Altai also showed that in the 9th-10th centuries, the Yenisei Kyrgyz not only penetrated the southern and western regions of Altai but also actively mixed with local Kimak and other Turkic tribes (Alekhin, 1985. P. 190). As a result, there was a convergence of the cultures of the Turkic tribes of Altai and the incoming Kyrgyz: numerous monuments testify to significant changes in the material culture of the local population, which adopted elements of zoomorphic and plant ornaments of the "Kyrgyz" style, associated with the emergence of the third stage of the Kuray culture in Altai (Savinov, 1984. P. 67; Tishkin 2007. P. 7).

During this same period, very close contacts were established between the Kyrgyz and the Toguz-Oguz or Uighur tribes of Tuva, Mongolia, and Eastern Turkestan. To expand their expansion across Central Asia, the Kyrgyz khans, after their victory over the Uighurs in 840, successively moved their camps from the northern foothills of the Sayan Mountains southward: first to the southern side of Tannu-Ola, and then to the city of Kemidzhiket in Central Tuva, where predominantly Toguz-Oguz (Uighur) tribes lived (Serdobov, 1971. P. 102). It seems that the legend by Gardizi about the arrival of the leader of the Kyrgyz in the settlement area of the Kimaks and Toguz-Oguz reflects these political actions of the Kyrgyz khans.

According to Chinese sources, a significant portion of the Uighurs, after the fall of their state in Mongolia, fleeing from the persecution of Kyrgyz troops, were forced to escape to other regions (Malyavkin, 1972. P. 29-35).

However, some groups of Uighurs continued to live in the territory of Tuva and Mongolia. Although they adopted the customs of the Kyrgyz, they managed to preserve their clan names: Ondar-Uighur, Saryglar, and others (Kyzlasov, 1969. P. 125). Probably, a similar fate befell another group of Uighurs, which, according to Abu'l-Ghazi Bahadur Khan, after the fall of the Uighur Khaganate, went northwest and settled in the forested areas of the Upper Irtysh (Klyashtorny, Savinov, 2005. P. 279).

Therefore, Gardizi's hints about the joining of the breakaway Toguz-Oguz from their ruler to the leader of the Kyrgyz are generally plausible and reflect the results of ethnic processes in the territory of Tuva, Altai, and the Irtysh region in the 9th-10th centuries. Ethnographic materials also show the presence of genetic connections between several Kyrgyz ethnonyms and the ethnic nomenclature of the ancient Turkic confederations of the Tele and Toguz-Oguz tribes (Abramzon, 1971. P. 52-55). The obvious connection of the ancient Turkic ethnonyms Tooles and Tardush with similar clan names of the Kyrgyz is also noted by Hungarian Turkologist K. Czegledi (Czegledy, 1972, P. 278).

In the process of mixing the Yenisei Kyrgyz with local Kimak-Kipchak and Toguz-Oguz tribes, the incoming tribes adapted to the new environment. It is evident that the local population of Altai and the Irtysh region adopted the self-name of the dominant tribal group, i.e., the Kyrgyz, which since the formation of the khanate has transformed into a political name. Gardizi's report that "to the tribe that gathered around him, he gave the name Kyrgyz" indicates the transfer of the ethnonym "Kyrgyz" into another ethnic environment and its transformation into a political name.

Thus, even before the Mongol conquest, the name "Kyrgyz" marked a heterogeneous group mainly of Kimak-Kipchak and some Toguz-Oguz tribes of Altai and the Irtysh region, gradually becoming a new ethnic community around the incoming Yenisei Kyrgyz. Therefore, there is every reason to believe that the distant echo of the changes that began on the northeastern border of the informational oikoumene of the Muslim world is the legend recorded by Gardizi about the contribution of the Kimaks and Toguz-Oguz to the formation of the Kyrgyz ethnic community on the Irtysh border of the Kyrgyz Khaganate.

The role and significance of the Altai-Teles tribes in the formation of the Kyrgyz people are reflected in its genealogy, where the mythical ancestor of all Kyrgyz tribes of the Tian Shan is Dolon-bi (Abramzon, 1971. P. 37,38). This anthroponym is closely related to the name of the Tuvan tribe Dolaans, which in turn goes back to the name of the ancient Tele tribes (Serdobov, 1971. P. 86). At the same time, the culture of the Yenisei Kyrgyz underwent certain changes under the influence of local tribes. It is precisely the Altai and eastern Kazakhstan variants that have a direct relation to the material culture of the Tian Shan Kyrgyz (Savinov, 1984. P. 89-97; Savinov, 1989. P. 81-84). These conclusions by D. G. Savinov almost completely align with the data from written sources on the history of the Kyrgyz language, ethnographic, and folklore materials.

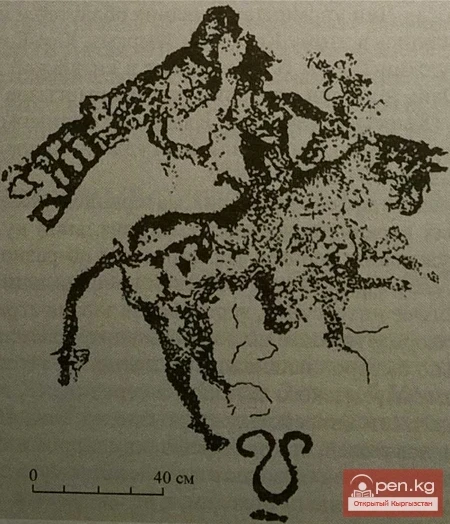

The influence of Kipchak culture is traced in the art objects of the Kyrgyz (Ivanov, 1959. P. 59-65). The presence of deep ethnogenetic ties between modern Kyrgyz and Altaians has also been confirmed in the studies of musicologists V. Vinogradov and Ch.T. Umetalieva-Bayalieva, who believe that the folk music of both is heptatonic and diatonic (Vinogradov, 1958. P. 23; Umetalieva-Bayalieva, 2008. P. 94, 95, 119, 135-137, 208). Turkologists and ethnographers also note the genetic similarity of the traditional calendar of the Kyrgyz, based on the count of the Pleiades, with the analogous calendar of the mountain Altaians and Barabin Tatars of Siberia (Bazin, 1991. P. 522).

The data provided by archaeology, ethnography, art, and evidence from written sources are also confirmed by linguists. According to specialists, it was in Altai that the Middle Kyrgyz language was formed, the speakers of which migrated to Tian Shan in the 15th century, where the process of forming a new Kyrgyz language was completed (Tenishev, 1989. P. 10, 16; Tenishev, 1997. P. 28; Oruzbaeva, 2004. P. 121).

Thus, by the beginning of the 13th century, in the Altai steppes of the Ob-Irtysh interfluve and in the foothills of Tarbagatai in Southeast Kazakhstan, there existed for over 200 years a group of Kimak-Kipchak and Toguz-Oguz (Uighur) tribes, which consolidated around the incoming Yenisei Kyrgyz and adopted the self-name "Kyrgyz".

This new ethnic group of Altai Kyrgyz inherited not only the self-name from the Yenisei Kyrgyz but also significant elements of material and spiritual culture. One of the key elements of spiritual culture is the common myth of the origin of the people from the descendants of 40 girls, which is recorded in the 15th-century Chinese chronicle "Yuan Shi" (Kychanov, 1963. P. 59). This legendary information in "Yuan Shi" is currently the only evidence from written sources about the common ancestry of the ancestors of the modern Kyrgyz people and the ancient Kyrgyz of Yenisei and Altai.

Formation of the Kyrgyz People in the IX-XVIII Centuries