Southern Kyrgyz Embroidery

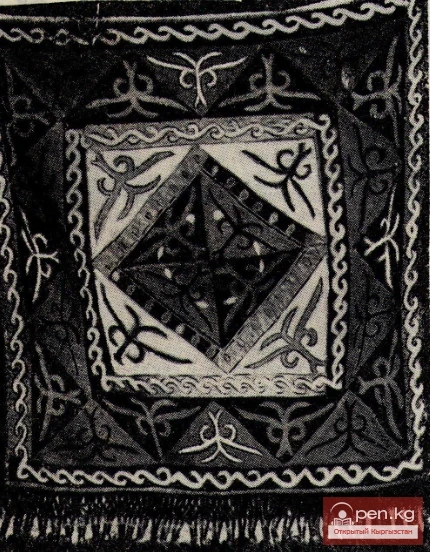

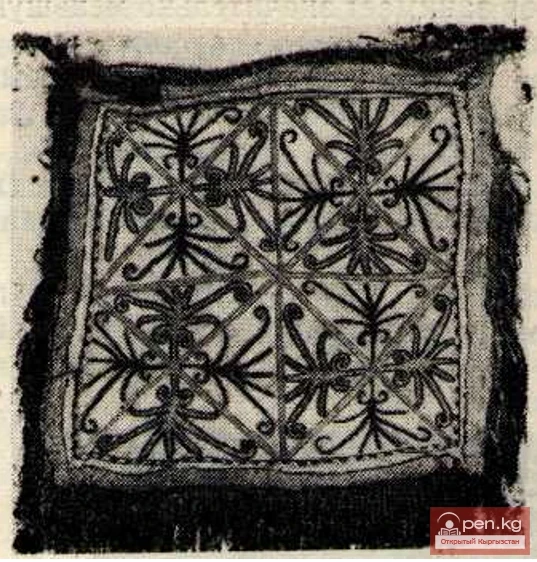

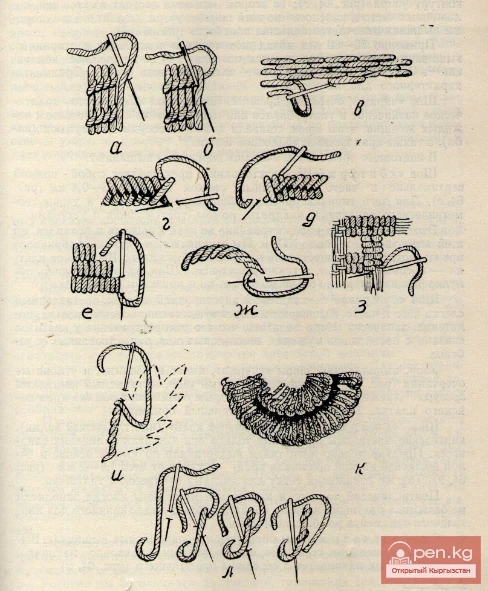

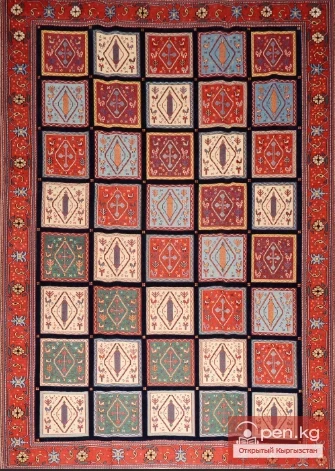

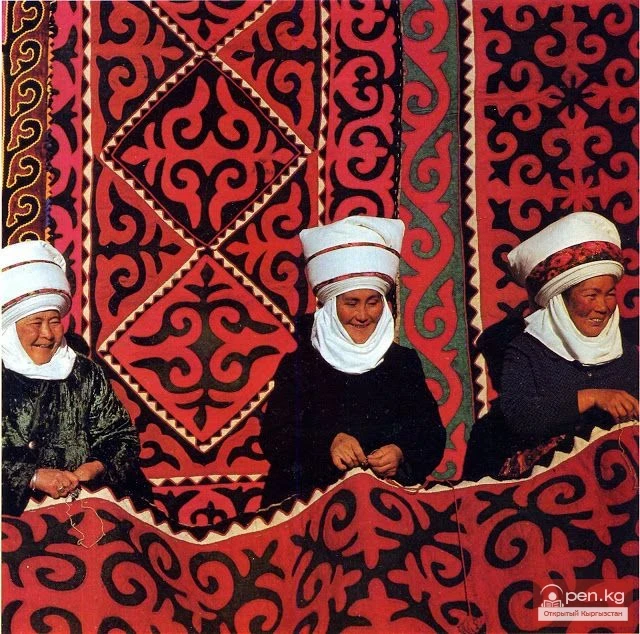

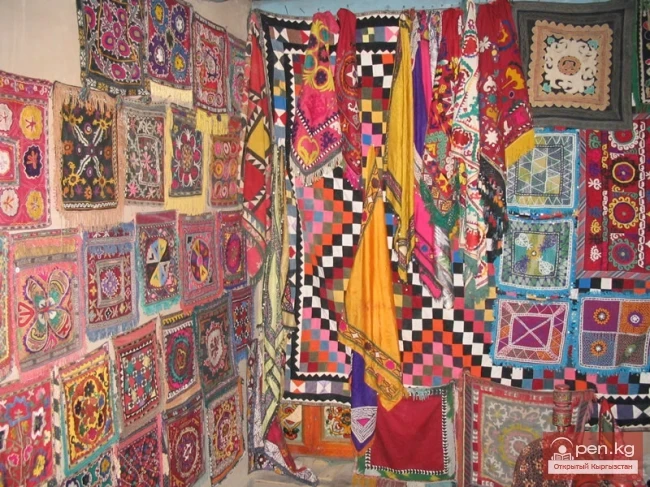

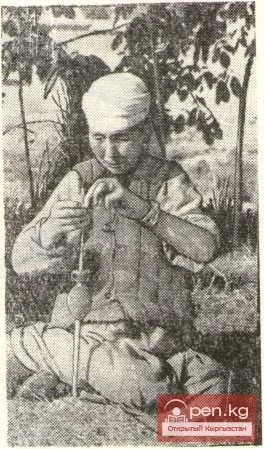

Embroidery of the Southern Kyrgyz Southern Kyrgyz embroidery is the result of centuries of artistic creativity. Its characteristic features are highly developed stylization and decorativeness. In recent years, there has been a more diverse technique here than among the northern Kyrgyz. Stitches such as "ilmidos," "duria," "mushkul," and "jormo" did not develop in northern Kyrgyz embroidery, while they are quite characteristic of the south. Among them,