Surface Stitches.

Surface stitches include the basma, buraya, chirash, kepturme, suurma, jormyo, and stem stitches.

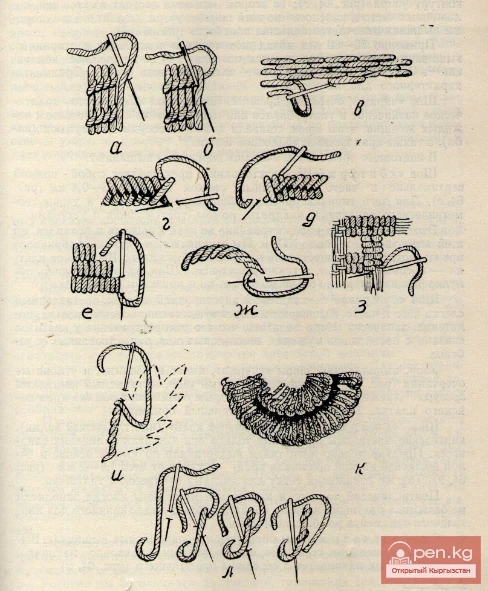

The "basma" stitch is executed by laying rows of threads across the width of the pattern. Each thread is attached to the material with stitches that are thrown over this thread in several places. The stitches create a peculiar linear (or mottled) ripple on the embroidered surface (see Fig. 64, a, b). On the reverse side of the fabric, the surface stitches leave linear gaps.

The Kyrgyz widely used the "basma" stitch in ancient times.

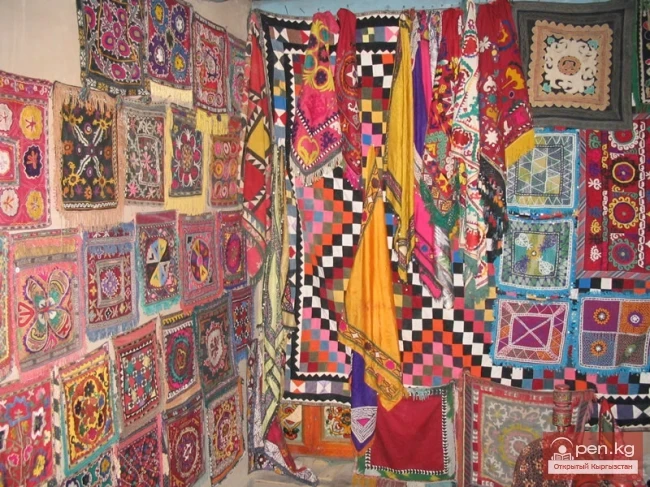

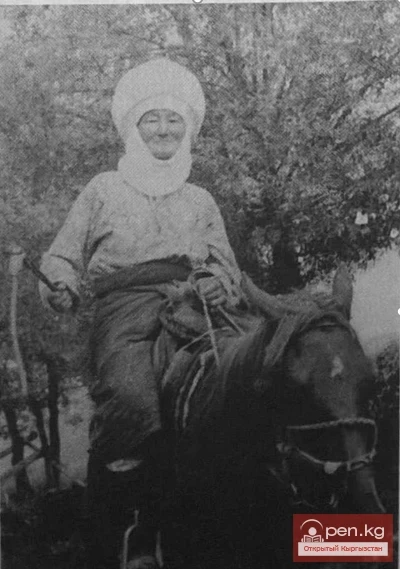

It was used in the embroidery of felt carpets, decorations on the inner side of the yurt's dome, wedding curtains, various household bags, and men's headwear "kalpak".

This stitch remains a favorite in all types of modern embroidery.

Like tambour stitches, the "basma" stitch is characteristic of Tajik and Uzbek embroideries, as well as ancient Chinese products, where it filled large areas of the pattern using brocade threads. I. N. Sobolev writes about the widespread use of this stitch in ancient times throughout the East.

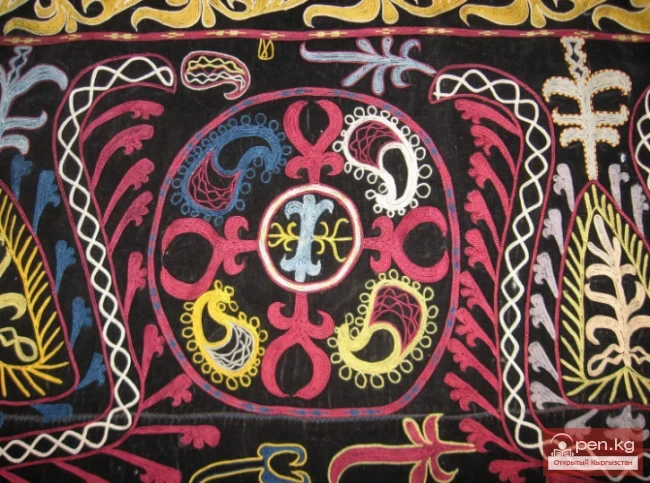

A special type of embroidery known as pat gul (see Fig. 64, k, l) is performed with the basma stitch and resembles a rosette with concentric circles of different colors. Each circle ends with a border formed by intertwining free threads, i.e., threads not sewn to the fabric. In the past, southern Kyrgyz used this type of embroidery to cover ties for women's turbans. Now, it decorates the corner of the waistband and pillowcases for the balysh.

The "pat gul" pattern is widespread in the southwestern part of the Osh region and is used by Uzbeks, who also decorate the edges of pillows and the corners of waistbands with it.

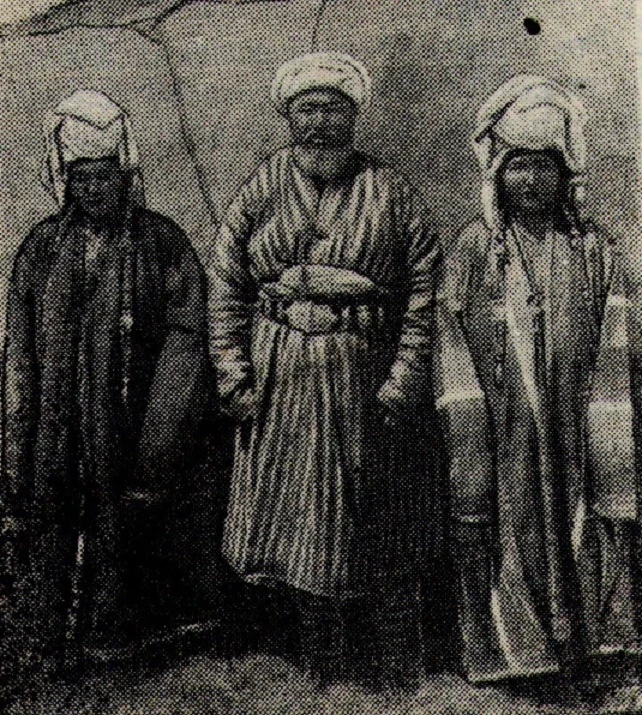

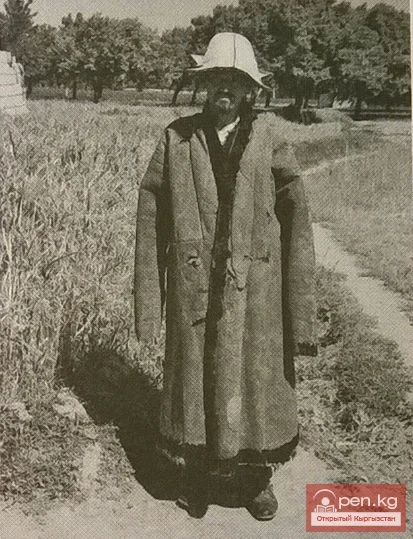

We also include the "dur and ya" stitch among surface stitches. This name is reminiscent of a decorative embroidered women's headscarf known to southern and Pamir Kyrgyz. The "duria" stitch was used to embroider these scarves, as well as decorations on women's headwear!

The "duria" stitch is double-sided, which is why some Kyrgyz artisans call it "eki juzduu". It creates a solid, dense layer of threads across the entire pattern, executed with stitches essentially using the "forward needle" technique (which is why sometimes artisans call this stitch "tepchime"), with the needle directed across the width of the pattern first in one direction, then in the opposite, using the same punctures (see Fig. 64, v). Embroiderers consider this stitch not easy, and some therefore call it "mushkul", i.e., difficult.

The limited use of the "duria" stitch, as well as the small number of embroiderers skilled in it, suggests that this stitch appeared among southern Kyrgyz under the influence of the fashion for embroidered scarves borrowed from neighboring peoples—Tajiks and Uzbeks—in the last quarter of the 19th century.

In terms of execution technique, the type of silk threads used for embroidery, their colors (red, blue, yellow, raspberry, pink), the embroidered material (thin white fabric), and the ornamentation, the "duria" embroidery is completely analogous to Tajik embroidery.

Currently, this stitch is rarely used. However, the patterns characteristic of it have fully integrated into southern Kyrgyz ornamentation.

The "chirash" stitch (cross stitch) externally resembles a dense fir tree and is formed by intersecting stitches. In terms of execution technique, this stitch has two variants: in the first, the reverse side consists of a solid line of side stitches running parallel to the contour of the pattern (see Fig. 64, g); in the second, the reverse side consists of stitches laid frequently and diagonally across the entire width of the pattern, while the front side of the embroidery shows greater density (see Fig. 64, d).

About 70-80 years ago, the "chirash" stitch was used in ancient embroideries on leather and felt, as evidenced by museum collections. The main purpose of the stitch is to fill the field of the pattern. There is no characteristic ornamentation for it.

The "chirash" stitch is evidently ancient. At one time, it had a purely practical purpose and was used for camouflage. According to elderly women's accounts, this stitch was used to sew leather vessels for kumys (saba), as well as the edges of wedges of felt hats.

Currently, Kyrgyz do not use the "chirash" stitch for embroidery.

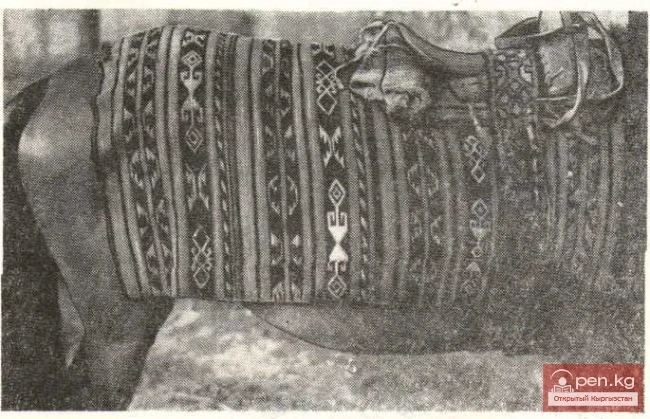

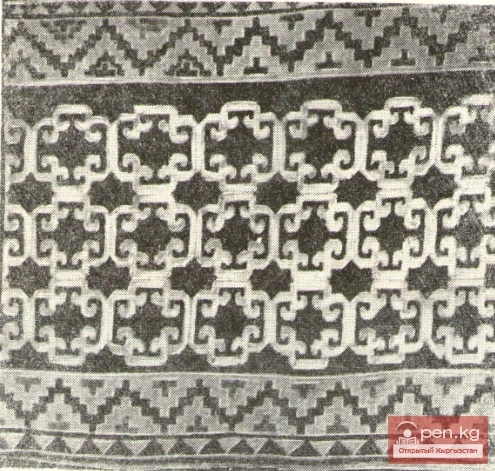

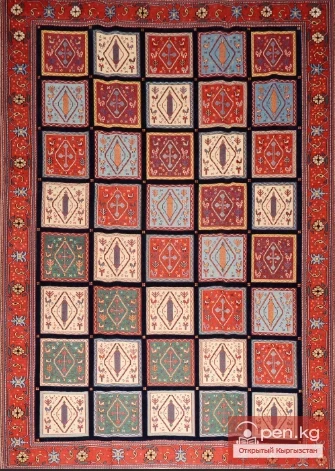

The "kopturmo" stitch is double-sided and consists of a straight vertical stitch often laid at a height of 0.3-0.4 mm (see Fig. 64, e). It is characterized by a straight arrangement and geometric patterns: squares, diamonds, triangles with steps.

This stitch has spread throughout Kyrgyzstan and likely appeared in the late 19th century. It is used for embroidery on factory-produced fabrics, predominantly cotton. It is used to embroider scarves—handkerchiefs, waistbands, as well as towels. The "kopturmo" stitch is very popular and known not only to young but also to elderly artisans.

The "suurma" stitch is a double-sided surface stitch, laid slightly diagonally and frequently. It is predominantly used for waist scarves, towels, and curtains. It is believed that its spread among Kyrgyz is associated with the appearance of men's waist scarves borrowed from Uzbeks.

The pattern executed with the "suurma" stitch has both smooth and angular outlines (see Fig. 64, zh). A characteristic zigzag pattern, called gungura (less often araa, i.e., saw) by Kyrgyz, usually borders the edges of the waist scarf.

A plant ornament is also characteristic.

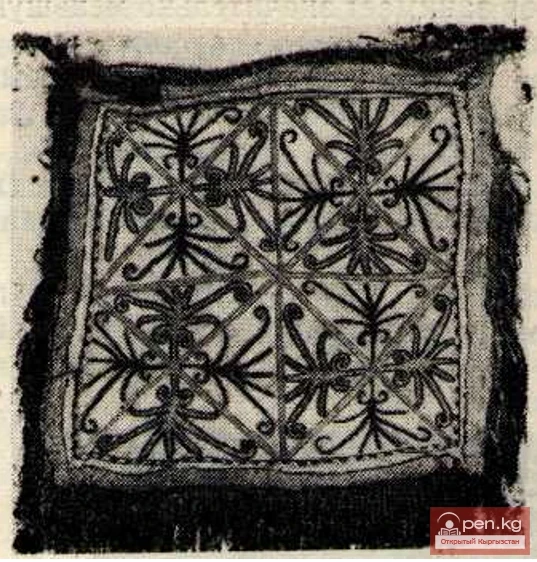

The "jormyo" stitch, i.e., the "edge stitch" (or surface roll), was used by Kyrgyz artisans only for embroidering face curtains. The threads of the fabric were initially pulled out along the weft and warp, and the edge was embroidered with white silk thread, retreating from it by 1.5-2 mm (see Fig. 64, z). Tajik women also embroidered the net for face curtains in the same way.

The center of the face curtain was sometimes filled by Kyrgyz artisans not with white but with colored threads, forming patterns in the shape of a typical Kyrgyz ornament diamond with curls.

The stem stitch is used in modern embroideries. It is executed with small stitches placed slightly diagonally. Each stitch begins from the middle of the previous one (see Fig. 64, i).

A brief overview of the stitches previously used and currently used in Kyrgyz embroidery allows us to note the changes in the embroidery art that have occurred during the time we studied. Some ancient stitches have been lost along with items characteristic of old life. Such are "terskayyk", "jermome" (small cross), half-cross, "jermyo", "chirash". The most enduring of the ancient stitches remain the looped stitches (except for overcasting), "basma", and stem stitches. They, along with the patterns accompanying these stitches, continue to be used even now. It is these that characterize the style of southern Kyrgyz embroidery, which has deep folk traditions.

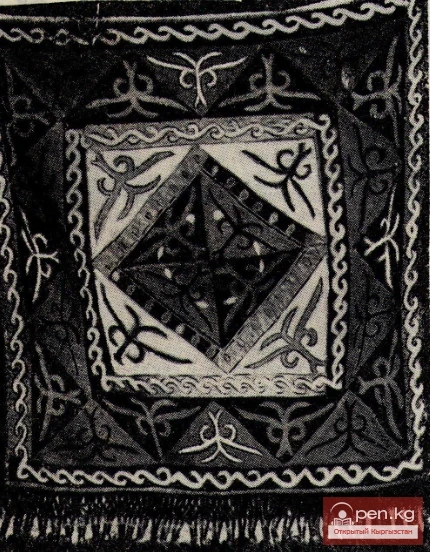

Characteristic of southern Kyrgyz embroidery are the "ilme" and "ilmedos" stitches. The first is leading, the second is filling. The "ilme" stitch, not tied to counting and based on a previously applied pattern, does not constrain the artistic creativity of the performer and provides wide opportunities for initiative.

Ancient Kyrgyz looped stitches ilme, ilmedos, tuura sayma