Kyrgyz Carpet Weaving

All three types of patterned fabrics, briefly described by us, are artistically unique and attractive. Currently, patterned weaving is in decline; primitive techniques are losing their strength literally every day. Only a transition to factory production (Jacquard machine) could preserve the age-old folk traditions and create beautiful decorative fabrics that fully meet modern tastes.

In the most substantial works related to the applied art of the peoples of Central Asia, which appeared in the first decades of our century, pile weaving is particularly well covered. This is explained by the fascination with Central Asian carpets at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries. Kyrgyz carpets are also gaining recognition.

The first serious work should be considered the albums by A. A. Bogolyubov, published in connection with the organization of a handicraft exhibition. A. A. Bogolyubov had the opportunity to collect an extensive collection of Central Asian carpets and wrote a study based on this. This was the first attempt at a scientific classification of carpets. The author focused primarily on Turkmen products.

The next study dedicated to Central Asian carpets is the work of A. Felkerzam. Providing a detailed description of Central Asian carpets, the author also introduces Kyrgyz carpets (mainly from the Ichkilik, Khyrysh, and Tiyr tribes). A. Felkerzam considers the main centers of Kyrgyz carpet production to be the Andijan and Osh districts of the Fergana region. Touching upon the products of Eastern Turkestan, the author concludes that the so-called Kashgar carpets are made by the Kyrgyz living there, who are, in the full sense of the word, artists in carpet production, and their products "belong to the best in Central Asia." The question of who made the Hotan carpets, whose style and technique differ sharply from the Kashgar ones, remains open. The author only mentions the assumption of S. M. Dudin, who attributes the production of these carpets "to one of the Uzbek tribes."

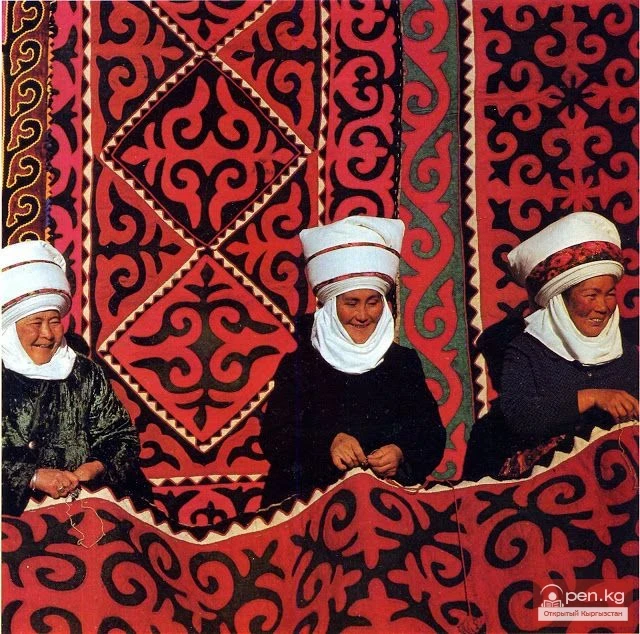

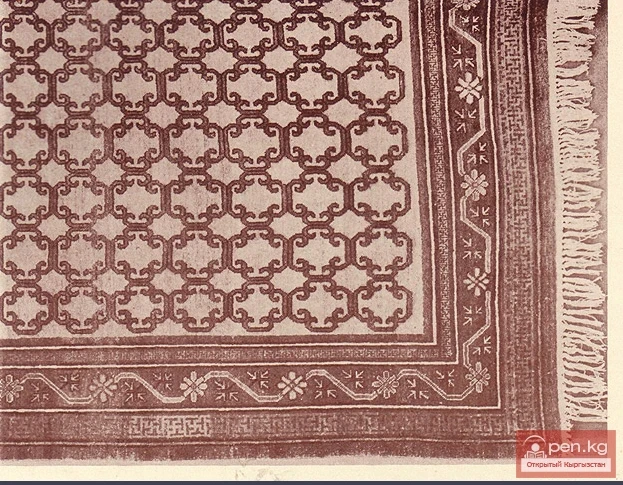

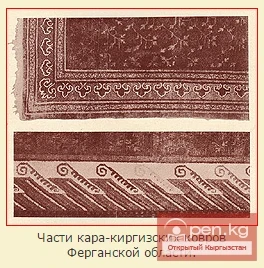

Part of a Kara-Kyrgyz carpet with a buckle pattern from the Fergana region.

A. A. Semenov's detailed work shows good knowledge of Kyrgyz carpet weaving. The author makes completely valid remarks regarding A. A. Bogolyubov's album. However, A. A. Semenov makes an inaccuracy by stating that "the Kyrgyz are engaged in carpet weaving in almost all districts."

Articles by some foreign authors are also of interest. A. Lekok, while on the Turfan expedition in 1911-1914, acquired several large Kyrgyz pile carpets, the description of which he provides with an accompanying table. The Swedish scholar Gunnar Jarring characterizes a Kyrgyz carpet acquired in Kashgar quite thoroughly.

A common feature of all the noted works on Kyrgyz carpets is that their descriptions, names of patterns, and conclusions reached by the authors were generally based on a small amount of specific material. A drawback of the early works on Kyrgyz carpets was also that most authors were forced to build their arguments on not entirely accurate materials, as they were obtained not directly from the carpet producers themselves, but from individuals "only familiar with folk life and carpet production."

A valuable contribution to the study of carpet products from Central Asia was made by S. M. Dudin. His work is based on materials he collected himself in Central Asia, as well as on critically processed studies by A. A. Bogolyubov, A. Felkerzam, and two works by German authors. Thus, S. M. Dudin systematized all the information available at that time about Central Asian carpets. Unfortunately, this work is not illustrated, but the tables provided with ornamental decorations of Central Asian carpet products, including those of the Kyrgyz, are valuable comparative material.

A valuable contribution to the study of carpet products from Central Asia was made by S. M. Dudin. His work is based on materials he collected himself in Central Asia, as well as on critically processed studies by A. A. Bogolyubov, A. Felkerzam, and two works by German authors. Thus, S. M. Dudin systematized all the information available at that time about Central Asian carpets. Unfortunately, this work is not illustrated, but the tables provided with ornamental decorations of Central Asian carpet products, including those of the Kyrgyz, are valuable comparative material.S. M. Dudin categorizes all Central Asian carpets into one general category, finding in them "something common" that sharply distinguishes them from Persian and Caucasian carpets.

Among Kyrgyz carpets, the author considers the products "Khyrysh" and "Mangit" from the Fergana region and, apparently mistakenly, from the Semirechye region.

In a brief essay by A. A. Miller, which serves as a guide to the ethnographic department of the Russian Museum exhibition, a description of carpet products from Turkestan is provided among others. Several examples of Kyrgyz pile carpets were also presented at this exhibition, in which, according to the author, Persian influence can be traced, which is hard to agree with.

Great scientific interest in Kyrgyz carpet weaving was shown by the Soviet scholar V. G. Moshkova, who collected valuable material and wrote several studies on Turkmen, Uzbek, and Kyrgyz carpet making. She also scientifically processed collections of Kyrgyz carpet products stored in the Museum of Arts of Uzbekistan.

Some other authors have also paid notable attention to Kyrgyz carpets. The range of questions related to the study of carpets is broad. Speaking about the value of the carpet as a product of folk creativity, researchers note two aspects of its study: the carpet as a historical monument, a source of knowledge about the history of the people, its character, everyday life, and connections with other peoples, and the carpet as a work of folk art, which has a tendency for further development.