A long time ago, when there was still no Issyk-Kul, and at the foot of the mountains there were no settlements, and people did not live here, as they do now, in cities and villages, legends say that there was a valley that occupied a vast territory — from modern Tyup in the east to the Boom Gorge in the west. A great river, Char, flowed through this valley, into which small rivers — Dzhergalan, Ak-Suu, Karakol, Kyzyl-Suu, Barskoon, Tamga, Kök-Terek, Ula-Khol — flowed. The waters of the river also fed numerous streams and mountain springs. Before the mountain Kyzyl-Ompol, the river Kochkor flowed into the Char — and all this avalanche of reddish-brown water rushed with a deafening roar in a wild stream through the narrow gorge of the Boom into the Chui Valley and went far beyond the mountains of Kazy-Kurt.

Thick reeds, shrubs, and trees grew along the banks of the Char River. People roamed the mountains with livestock and in those distant times set up their dwelling — a yurt, choosing a better place: the neighbor was far from the neighbor, so there was often no one to communicate with, and if someone settled on the opposite bank of the Char River, there was no way to reach him: no bridges connecting the steep banks were built.

The pastures and lands on one bank of the Char River were owned by Khan Oshpur — a cruel, unsociable, and extremely harsh man. The people say that the Khan did not spare even a mouse if it happened to cross his path at an inopportune time, and he chased flies with a long whip if they had the audacity to land on his nose while he was resting. The people feared Oshpur like fire, obeyed him unconditionally in everything, and... were astonished by his tyranny. And there was much to be astonished about.

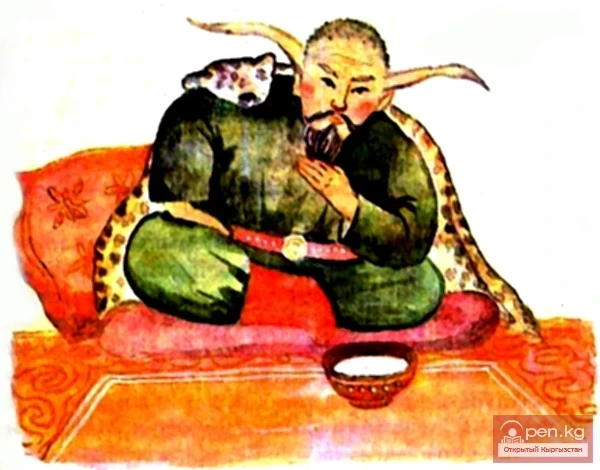

Khan Oshpur possessed great wealth and power; he had his own palace, but he hardly interacted with the courtiers, did not appear among the people, did not go hunting, and no one had ever seen him up close. If any of his tribesmen came to him with a complaint, he received the petitioner seated on his throne, and no one dared to approach him or even look at him. During mass public festivities and celebrations, the Khan watched the games and competitions from the top of his favorite hill.

The people would have forgiven the Khan his eccentricities and reclusiveness, but Oshpur was also immeasurably greedy and cruel: once every ten days, he imposed taxes on the people and, besides livestock, skins, and grain, he insisted on sending a young man to his palace; every ten days — one young man. That young man then disappeared without a trace within the walls of the Khan's palace: the parents of the youth were left to mourn the loss of their son for the rest of their lives.

Who would find such a rule of the Khan pleasing? Naturally, no one. The people whispered among themselves, discussing how to save their sons, but no one could come up with anything: the Khan dealt cruelly with those who dared to oppose him.

And in this Khan's kingdom lived an old man named Abygiy. The old man had only one son named Adyrgy — his sole support and hope... One day, it was Adyrgy's turn to go to the palace. Saying goodbye forever to his son, old Abygiy wept for a long time, and his wife Maasymkan cried bitterly as she sent her son off to uncertainty and doom. The grief of the old people was understandable — they knew there was no return from the palace. But what could the poor people do against the treacherous Khan Oshpur? They had only one means left — a spell. And that is what the old people decided to resort to: perhaps it would help...

Old Maasymkan, even in her years, was still a strong woman. From her breast, she poured half a bowl of milk and kneaded dough from it, from which she baked boorsoks.

— Take these boorsoks, my son, — said the mother at parting, — and try to feed them to the Khan. Do not eat any yourself, and if by chance you must — as soon as you eat, drink cold water. If you do otherwise — something bad may happen, and be careful — do not drop the baked goods on the ground...

The Khan's messengers brought Adyrgy to the palace, to the very chambers of Oshpur. They did not dare to enter the room themselves, leaving Adyrgy alone with the Khan. The Khan looked piercingly at the young man and said:

— Now you will shave me, so that not a single hair remains on my face or head. Just do not shave my mustache and beard, just trim them a little...

The young man was prepared for the worst, but this task seemed easy to him.

Meanwhile, Oshpur sat on his soft couch and removed his headdress. Oh, horror! The Khan had half-meter-long ears! Adyrgy saw not just long ears; they resembled both donkey and pig ears at the same time — they were of such an ugly shape. The young man examined the Khan and guessed that the tips of the ears were tied with a silk ribbon, and then neatly laid and hidden under the headdress — no one had ever seen the Khan's ears.

Adyrgy untied the ribbon, and the ears fell and hung lower than the beard. Now the Khan looked like a pig from the front.

"So that's why the Khan does not show himself to the people," thought Adyrgy, "and that's why young men disappear in the palace," he realized. "To ensure that no one learns about the Khan's ears, he kills the barbers. And he will kill me too, to prevent me from telling anyone."

But there was nothing to be done, and Adyrgy slowly began to shave the Khan's head. His heart ached with despair; he could think of nothing to even attempt to save himself, and suddenly he remembered his mother's instructions.

The nine boorsoks that his mother had given him, Adyrgy hid in his sleeve. He had already shaved the top of the Khan's head and now cautiously and discreetly tossed one boorsok directly into the Khan's hands, which were resting on his knees.

"Allah himself sends me boorsoks," thought the greedy Khan, seeing the boorsok that had appeared from nowhere, and immediately ate it. The second followed... the fifth... the eighth...

Adyrgy, busy with his task, did not remember how many boorsoks the Khan had eaten: his sleeve seemed empty when he finished shaving the head, cheeks, and trimming the mustache and beard. And only when the young man had tied up the ears with a ribbon and put the Khan's beautiful headdress on his head did he feel that one boorsok was stuck in his sleeve.

Adyrgy was genuinely frightened: the Khan had not eaten all the boorsoks, as his mother had instructed, and now he would find out how he had been mocked, and Adyrgy would not fare well.

— Well, young man, it seems you have done your job, — said Oshpur, stretching his legs that had gone numb from sitting for too long. — Now pray to the Creator and prepare for death. I will kill you myself, so that there will be no witness to what you have seen. With this saber, I will take off your head in one blow, you will not even feel anything... your death will be so light...

— No, Khan, you will not be able to kill me! — Adyrgy replied firmly.

— Why not? — The Khan did not expect such words; it was clear he had never faced resistance before.

— Because we are milk brothers! You cannot kill your own brother.

— When did I become your milk brother? — the Khan sneered harshly. — I am the Khan, and who are you? I am even older than you...

— Ah, but when I was shaving and trimming, you were eating boorsoks?

— Let’s say I did. What of it? They fell right from the sky to me. Because I am the Khan...

— No, Khan, the boorsoks did not fall from the sky by themselves. That cannot be. I was the one who threw them to you. And the dough for the boorsoks was kneaded with my mother’s breast milk. So now we are milk brothers and have no right to kill each other.

— So, you outsmarted me. Oh, how unpleasant this turned out! But what to do? Now you know my secret about my ears. No soul should know about them. Not even your own father and mother. Forget about my ears. Only you and I will know about them. From now on, you will be my only barber, but remember, if you tell anyone — do not expect mercy. I will kill you, your parents, and everyone who hears from you about my ears. Give me your word that you will remain silent, and go...

— I give it, — said Adyrgy.

— Then go, — and the Khan let the young man go.

Adyrgy joyfully went out into the courtyard. He lowered his tired hands from shaving. At that moment, the ninth boorsok fell from his sleeve to the ground. He quickly grabbed the boorsok and, looking around to see if anyone was watching, decided what to do. "Should I take it to Khan Oshpur? What will he think? He is unlikely to eat it... Most likely, he will chop off my head." To avoid catching the Khan's eye and incurring his wrath, Adyrgy took the boorsok and ate it.

His stomach immediately began to swell and grow like a balloon. In search of salvation, Adyrgy dashed around the courtyard and remembered his mother's instructions. He rushed to the well and began to drink cold water — bucket after bucket. Not knowing what he was doing, he chanted:

— Khan — donkey, pig ears! Khan — donkey, pig ears!

Finally quenching his thirst and calming down, realizing that nothing bad had happened to him, Adyrgy headed home.

His elderly parents could not believe their eyes when they saw their son alive and unharmed, but no matter how much they asked him, Adyrgy, true to his word, did not tell them anything about the Khan.

The Khan woke up the next morning to the noise in the courtyard. Never had this happened before; who dared to disturb his peace?

The Khan looked out the window. Around the well, the courtiers were gathered, laughing uproariously, holding their bellies.

Oshpur stealthily approached them, listened to what his servants were laughing about, and could not believe his ears: all the grasses, flowers, shrubs, and trees growing by the well were whispering in Adyrgy's voice: "Khan — donkey, pig ears! Khan — donkey, pig ears!"

— Ah, you son of a dog, you blabbed! — cursed the Khan and dashed around the courtyard.

"Cursed be it! — the memory of Adyrgy choked him. — Now not only people know the truth about my ears, but even the plants. Better to drown myself and drown everyone than to endure such shame, and the people will begin to take revenge on me..."

Khan Oshpur lifted the lid of the well — water gushed from it like a fountain. It quickly filled the courtyard, penetrated the palace, spilled onto the street — and flowed down the valley, ever increasing, flooding everything and everyone in its path. It is said that only the old man Abygiy, with his wife Maasymkan and son Adyrgy, managed to escape. They managed to gallop away into the mountains on a swift-footed camel. Underwater remained both the palace and the city, and the valley and the trees. The Char River ceased to flow into the Chui Valley. And it is also said: the water of the lake that formed, swallowing both the palace and the Khan himself, was warm, warm, so the lake was named Issyk-Kul — Hot Lake.