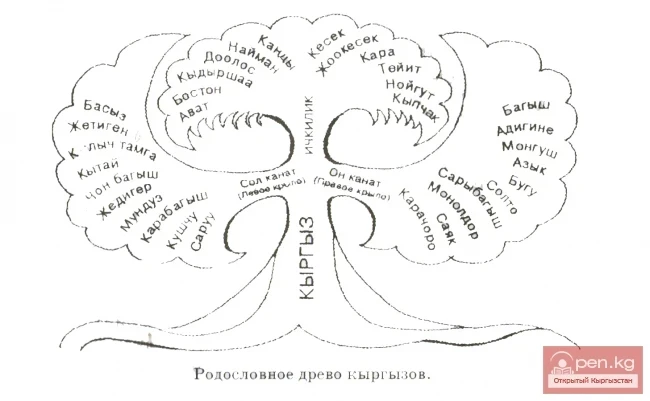

The Extermination of the Kyrgyz Tribe

This happened a long time ago. In ancient times, when there were more forests on earth than grass, and the waters in our lands were more abundant than the dry land, there lived a Kyrgyz tribe on the banks of a large and cold river. That river was called Enesai. It flows far from here, in Siberia. It takes three years and three months to ride there on horseback. Now this river is called Yenisei, but at that time it was called Enesai. That’s why there was a song like this:

Is there a river wider than you, Enesai,

Is there a land dearer than you, Enesai?

Is there sorrow deeper than you, Enesai,

Is there freedom freer than you, Enesai?

There is no river wider than you, Enesai,

There is no land dearer than you, Enesai,

There is no sorrow deeper than you, Enesai,

There is no freedom freer than you, Enesai.

Such was the river Enesai.

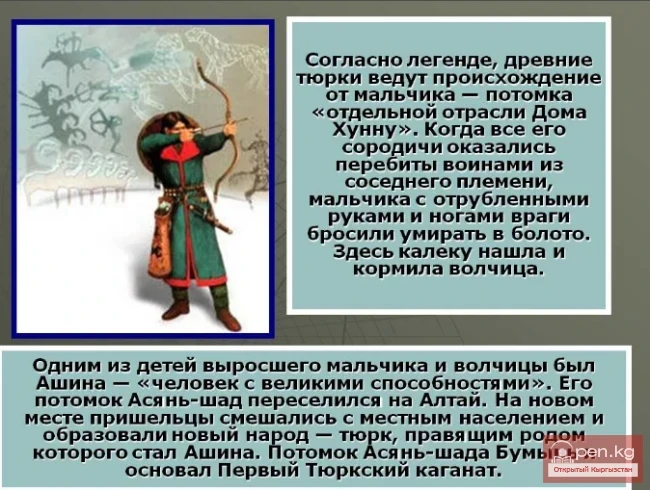

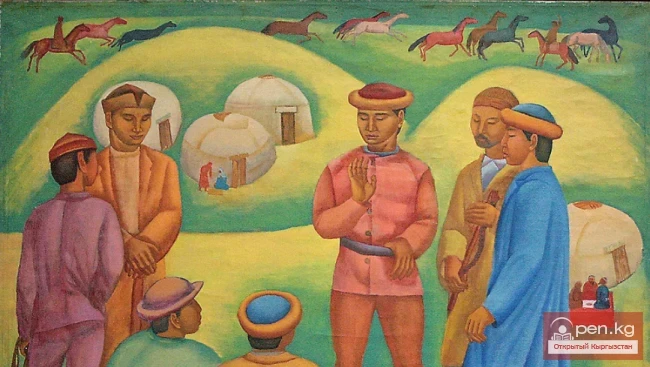

Different peoples stood by the Enesai at that time. They had a hard time because they lived in constant enmity. Many enemies surrounded the Kyrgyz tribe. Sometimes one group attacked, sometimes another, and sometimes the Kyrgyz themselves would raid others, stealing cattle, burning homes, killing people. They killed everyone they could kill — such were the times. A person did not spare another person. Man exterminated man. It got to the point where there was no one left to sow bread, multiply cattle, or go hunting.

It became easier to live by robbery: come, kill, take. And for murder, one had to pay with even more blood, and for revenge — with even greater vengeance. And the further it went, the more blood flowed. People’s minds became clouded. There was no one to reconcile the enemies. The smartest and the best were considered those who could catch the enemy by surprise, slaughter the enemy tribe to the last soul, seize herds and riches. A strange bird appeared in the taiga. It sang, wept at night with a human lamenting voice, and chirped as it flew from branch to branch: “A great disaster is coming! A great disaster is coming!” And so it happened, that terrible day arrived.

On that day, the Kyrgyz tribe by the Enesai was burying its old leader. For many years, the hero Kulche had led them, going on many campaigns and fighting in many battles. He survived in battles, but the hour of his death had come. His tribesmen mourned for two days, and on the third day, they gathered to lay the hero to rest. According to ancient custom, the leader's body was to be carried on the last journey along the bank of the Enesai over the cliffs and precipices, so that from the heights the soul of the deceased could stretch out with the mother river Enesai, for “ene” means mother, and “sai” means riverbed, river. So that his soul could sing one last song about the Enesai.

Is there a river wider than you, Enesai,

Is there a land dearer than you, Enesai?

Is there sorrow deeper than you, Enesai,

Is there freedom freer than you, Enesai?

There is no river wider than you, Enesai,

There is no land dearer than you, Enesai,

There is no sorrow deeper than you, Enesai,

There is no freedom freer than you, Enesai...

At the burial mound by the open grave, it was customary to raise the hero above their heads and show him the four cardinal directions: “Here is your river. Here is your sky. Here is your land. Here we are, born from the same root as you. We all came to see you off. Sleep peacefully.” In memory for distant descendants, a stone slab was placed on the hero's grave.

During the funeral, the yurts of the entire tribe were arranged in a chain along the bank so that each family could say goodbye to the hero at their doorstep when his body was carried for burial, bowing to the ground with a white flag of mourning, wailing and crying, and then going together to the next yurt, where they would again lament and cry and bow the white flag of mourning, and so on until the end of the way, to the very burial mound.

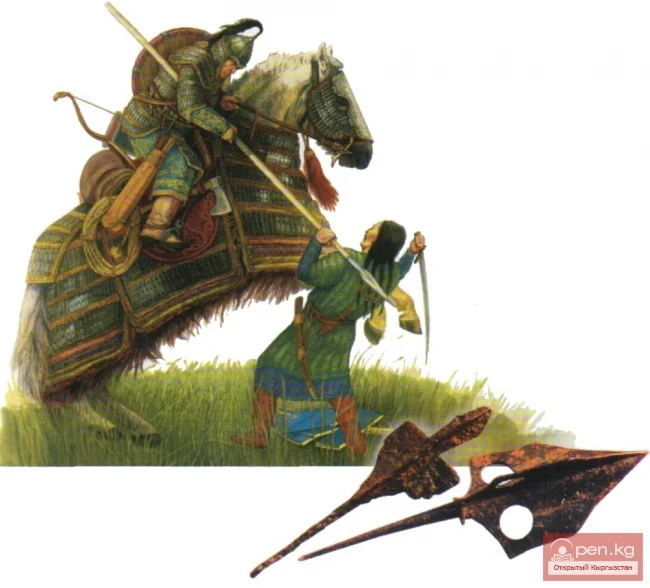

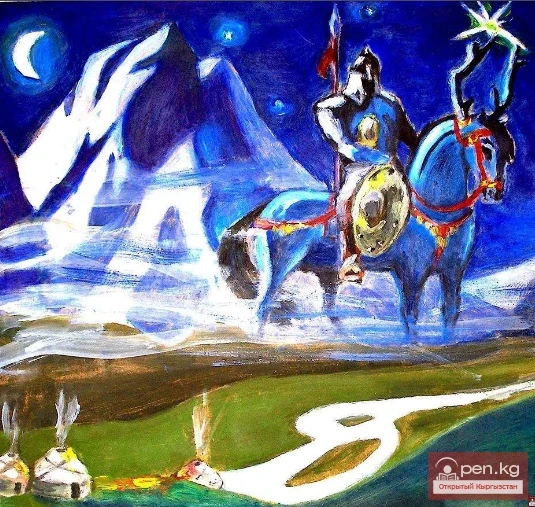

On the morning of that day, the sun was already on its daily path when all preparations were completed. The banners with horse tails on the poles were brought out, the hero's battle armor — shield and spear — were brought out. His horse was covered with a burial shroud. The trumpeters prepared to play the battle trumpets, the drummers to beat the drums — dobuls — so that the taiga would sway, so that birds would rise to the sky in flocks and swirl with noise and groans, so that beasts would run through the thickets with wild snorts, so that the grass would press to the ground, so that the echo would roar in the mountains, so that the mountains would tremble. The mourners let their hair down to sing in tears for the hero Kulche. The horsemen knelt to lift his battle body onto their strong shoulders. Everything was ready, waiting for the hero to be carried out. And at the edge of the forest stood nine sacrificial mares, nine sacrificial bulls, and nine sacrificial sheep for the memorial feast.

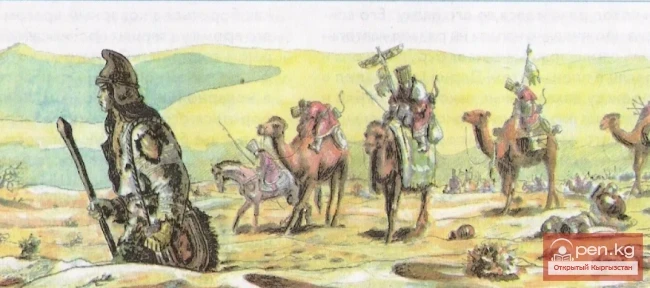

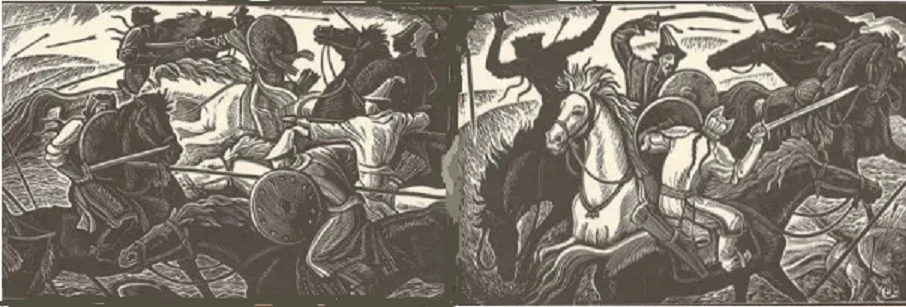

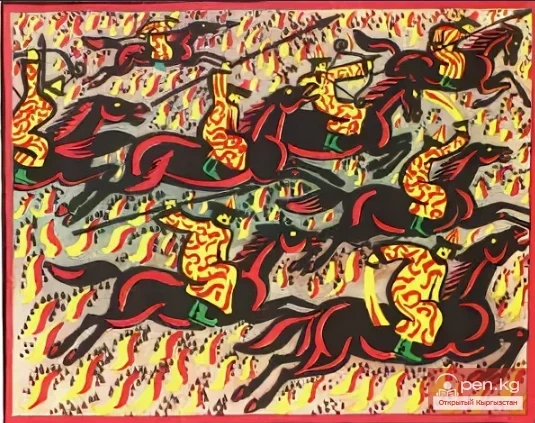

And then something unforeseen happened. No matter how much the Enesai people were at odds with each other, it was not customary to go to war against neighbors during the funerals of leaders. But now hordes of enemies, who had stealthily surrounded the sorrowful camp of the Kyrgyz at dawn, sprang from their hiding places from all sides, so that no one had time to mount their horses, no one had time to grab their weapons. And an unprecedented massacre began. They killed everyone indiscriminately. It was planned by the enemies to finish off the daring Kyrgyz tribe with one blow. They killed everyone so that no one would remember this atrocity, no one would seek revenge, so that time would cover the traces of the past with shifting sands. It was — it was not...

It takes a long time to give birth to and raise a person, but to kill is quick. Many were already lying cut down, drowning in pools of blood, many rushed into the river, escaping from swords and spears, and drowned in the waters of the Enesai. And along the bank, along the cliffs and precipices, Kyrgyz yurts burned for whole miles, engulfed in flames. No one had time to escape, no one was left alive. Everything was destroyed and burned. The bodies of the fallen were thrown from the cliffs into the Enesai. The enemies rejoiced: “Now these lands are ours! Now these forests are ours! Now these herds are ours!”

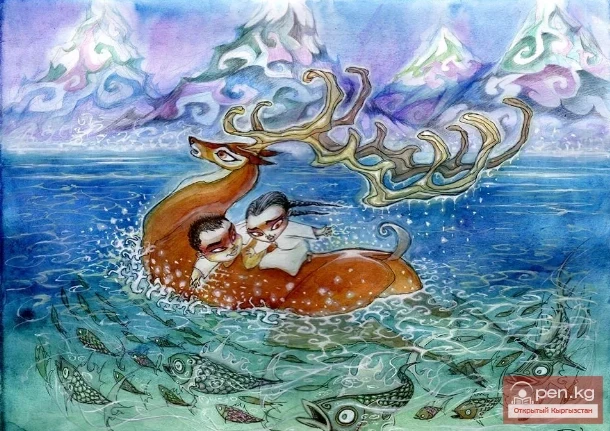

With rich spoils, the enemies left and did not notice how two children — a boy and a girl — returned from the forest.

Naughty and mischievous, they had secretly run to the nearest forest that morning to gather willow branches for baskets.

They got carried away and did not notice how deep they had gone into the thicket. And when they heard the noise and cries of the battle and rushed back, they found neither their fathers, nor their mothers, nor brothers, nor sisters alive. The children were left without kin, without tribe.

They ran weeping from ashes to ashes, and there was not a single soul anywhere. They became orphans in an instant. They were alone in the whole world. And in the distance, a cloud of dust swirled, the enemies were driving away the herds and flocks seized in the bloody raid.

The children saw the dust of hooves and set off in pursuit. They ran after the fierce enemies, crying and calling out. Only children could act this way. Instead of hiding from the killers, they set off to chase them. Just to not be left alone, just to get away from the devastated cursed place. Holding hands, the boy and girl ran after the drive, asking them to wait, asking to take them along. But where could their weak voices be heard amidst the roar, the neighing, and the thundering of the hot chase! The boy and girl ran in despair for a long time. But they never caught up. And then they fell to the ground.

They were afraid to look around, afraid to move. They were terrified. They huddled close to each other and did not notice how they fell asleep.

To be continued...