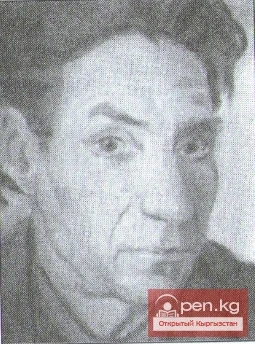

Suleiman Yunusovich Kuchukov (1889-1932)

Historically, it happened that the author of these lines learned to read at a time when all participants in the struggle against the basmachi, who survived it (and those who were killed for some reason in the following years) began to write memoirs. That is, they may have written them earlier. But in the late 50s and early 60s, they began to be published in large numbers, mainly in local publishing houses, but in mass (for those times and conditions) editions.

These books were available in any district, school, and village libraries. Sometimes they were even sold in village shops.

This was practically the only source of information about certain pages of that war, which is commonly referred to as the Civil War. Besides, of course, the stories of old people who still remembered the names of the legendary commanders of the Red Army and the Turkestan cavalry, and their opponents — the kurbashis of the basmachi detachments. Among such names is Suleiman Kuchukov, who happened to be in both roles. And before that, he was also an officer in the Russian army.

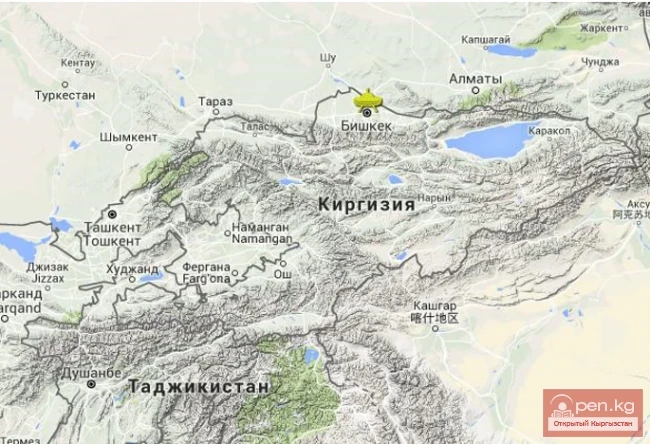

There is little reliable information about Kuchukov's biography, although there are plenty of legends. It is believed that he was born in 1889 in one of the ails near the fortress of Gulcha (now in the Osh region of Kyrgyzstan). By origin, he was a Kyrgyz or, as they said then, a kara-Kyrgyz, because the Kazakhs were referred to as Kyrgyz (or Kyrgyz-Kaisaks) at that time. At about the age of 10, he was adopted by a Tashkent merchant, Yunus Kusukov (of Bashkir or Tatar origin), from whom he inherited his surname (Kusukov and Kuchukov are variants of pronunciation) and patronymic (in Soviet sources — Yunusovich). Moreover, his adoptive father, being apparently not the last of the poor, was able to provide Suleiman with a decent education, including at the Orenburg Cadet Corps (named after "Nepluev" in honor of Ivan Ivanovich Nepluev, the "organizer" of the Orenburg region, 1693–1773).

Kuchukov graduated from the corps as a second lieutenant (in 1909). There is no information about his further service until World War I, when, as a lieutenant, he commanded the reconnaissance unit of the 1st Turkestan Rifle Regiment. By the Highest Order of April 25, 1915, he was awarded the Order of Saint George, 4th class — the name of Suleiman Kuchukov can be found in the corresponding lists.

But then the legends begin. Sources contain information that Kuchukov was a full cavalier of the Order of Saint George and a cavalier of the Order of Saint Anna. The first cannot be true because it could never be: no one had the full George ribbon during World War I.

Georgian cavaliers are also called those awarded the Military Order's Distinction — the so-called George Cross (or simply "Yegory"). And it seems that there were quite a few holders of the "full Yegory ribbon" during the First German War (judging by the fact that seven of them, including Semyon Mikhailovich Budyonny, also became Heroes of the Soviet Union). However, according to the statute, the Distinction was awarded only to lower ranks — so Officer Kuchukov could not be among them.

However, after the February Revolution, the Provisional Government amended the statute of the Distinction — now officers could also be awarded for personal bravery (by decision of the soldiers' assembly of the unit). But it is somewhat difficult to imagine a situation where, from June 1917 (the amendment of the statute) to the October Revolution, any officer was honored with such an award four (in words — four) times.

In the second fact itself — the award of the Order of Saint Anna — there is nothing incredible. Except for one thing — I could not find the name Suleiman Kuchukov in the lists of cavaliers of this order.

There is also another beautiful legend associated with Kuchukov and the orders (I could not trace it back to the primary source). It states that on one of the (unspecified) days of the First German War, Suleiman and his reconnaissance team were called to retrieve the body of a fallen Russian general from the battlefield. This was accomplished. And an English military observer, struck by Kuchukov's bravery and skill, immediately awarded him the Victoria Cross — the highest military award of Great Britain.

The beauty of this legend is overshadowed, as in the previous case, by one small detail: in the register of Victoria Cross holders, nothing resembling the name "Suleiman" or the surname "Kuchukov" can be found in any transcription. Although…

… if we recall the story of the awarding of British Orders of Saint Michael and Saint George to a certain general from Kharkov, which occurred during the Civil War, there is nothing incredible in this case either. As is known, at that time the orders, due to the absence of the named general, were awarded to Lieutenant General of the Russian service Mai-Maevsky (the same one whose adjutant served His Excellency). It is interesting whether this fact found reflection in bureaucratic documents?

However, all that has been said is purely the realization of the pedant's regime. And in no way aims to doubt the valor of Suleiman Kuchukov. Which he had plenty of occasions to confirm later.

Because later the October Revolution occurred, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. And the traces of Kuchukov disappear — until the time when in the summer of 1919 he finds himself a kurbashi of a detachment (staffed by his fellow kara-Kyrgyz) in the army of Madamin-bek — the leader of the Fergana basmachi ("amir lashkar bashi") and one of the most peculiar basmachi leaders in general. It is enough to note that, besides Kuchukov's "gang" (the composition of which can only be guessed), in Madaminbek's "super gang" was the Pamir Border Detachment of Staff Captain Plotnikov, the Wolf Hundred of the ensign Farynsky, among his military advisors were General Mukhano of the Russian service and the brother of General Kornilov, who entered history under the pseudonym "Belkin." In the sources available to me, only his initials remain — A.G. Kornilov had another brother, Pyotr, accordingly, Georgievich, who died during the First Kuban Campaign (the "Ice" one).

By the way, in the "gang" (or "government" — however you like) of Madamin-bek, there was even a Minister of Internal Affairs and Law Enforcement. This role was performed by a certain Nensberg (of nationality, as you can easily guess, a lawyer) — known even before the war as a "bandit" lawyer, who defended basmachi leaders when they were tried during the cursed tsarist regime.

The epic of Madamin-bek is a completely separate story. However, according to the memoirs of his then opponents, that is, the red commanders and commissars, Suleiman Kuchukov proved himself a worthy enemy in the service of the amir. He was not afraid, among other things, to enter into conflicts with other kurbashis of Madamin-bek, among whom were religious fanatics, outright criminals, and pathological sadists (but that is also from another opera). And for whom his "bandits," the kara-Kyrgyz, were ready to skin anyone. Which they once almost did with Khal-Khodzha — one of those very criminals and sadists.

Suleiman Kuchukov's war against the Soviet power ended in January 1920. When he, in the company of Mukhano, Kornilov-"Belkin," and Nensberg, surrendered in the Gulcha fortress under the honest word of the commander of the 6th brigade, Paramonov, a former captain of the Russian service. He surrendered along with his entire "gang" of about 600 sabers. From which, by order of the eastern man Frunze, the Kara-Kyrgyz National Regiment was formed under the command of its former kurbashi — Suleiman Kuchukov.

This regiment (in some sources — division) participated in Frunze's Bukhara campaign, in battles with Kurshirmat and Muetdin-bek, who claimed the title of "amir lashkar bashi" after Madamin-bek, who also surrendered to the Soviet power, was killed by Khal-Khodzha. According to one legend, Frunze personally awarded Kuchukov with his own Order of the Red Banner. Which, of course, is no more likely than the legend of full Georgievsky knighthood. However, Kuchukov did become a cavalier of the Order of the Red Banner, albeit later — by order of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic No. 157 in 1923.

In one of the battles with Kurshirmat, near the village of Jugara-Garbua, Kuchukov received a serious wound, which affected him a few years later — and in 1923 he was discharged. He worked at the Osh and Jalalabad horse-breeding farms — for he, like any Kyrgyz, was a born horseman. Again, according to legend, he was the initiator of the creation of the Tashkent racetrack.

In various sources, you can find different years for Kuchukov's death — 1930 or 1932. According to one version, he was killed by former "comrades in struggle" — relatives of the basmachi kurbashis. According to another — he fell victim to one of the campaigns to rid the Soviet Turkestan of "excess" participants in the struggle. Which, however, does not contradict one another: many former kurbashis somehow turned out to be prominent Soviet and party workers. But that is a completely separate topic.

That is all I managed to gather about this man over 50 years — a Russian officer, basmachi, red commander.

And it all started with this book: Mark Polyakovsky. The End of Madamin-bek. 1966, I no longer remember which Tashkent publishing house.

The author is a participant in all events starting from March 1919, with the siege of Namangan by Madamin-bek and Osipov. The book is written brilliantly — I do not know whose contribution to this is greater, the author’s or the literary editor, Ed. Arbenov.

His relative, Vladimir Polyakovsky, is a well-known Central Asian geologist, a specialist in thermobarogeochemistry.

I did not have the chance to ask about the degree of kinship; by the number of generations, he should be a grandnephew.

There is also another book: Sergey Kalmykov. "Koran and Mauser," 1968, also a Tashkent publishing house.

The author is apparently also a participant in the events (he clearly appears under a pseudonym). But, unlike the previous book, this is more of a novel than actual memoirs. The names of many active figures are changed, although the characters themselves are recognizable. In particular, the hero of this essay appears there as Osman Buchukov (if memory serves).

And you can find fragmentary information about Suleiman Kuchukov online — although far from always can they be perceived as documentary evidence.

Suleiman Kuchukov's daughter, Rafaat Kuchlikova, is an opera singer at the Alisher Navoi Theater in Tashkent.

She is famous for performing roles in a number of operas, primarily — Cio-Cio-san in "Madama Butterfly." However, nowadays, not much information can be found about her either. Except for this photograph:

P.S. "In all of history, only four people became full Georgievsky cavaliers: M.I. Goleniщev-Kutuzov, M.S. Barclay de Tolly, I.F. Paskevich, and I.I. Dibich-Zabalkansky."

Alexey Fedorchuk: 27/01/2016