Ancient Kyrgyz under the Rule of the Huns

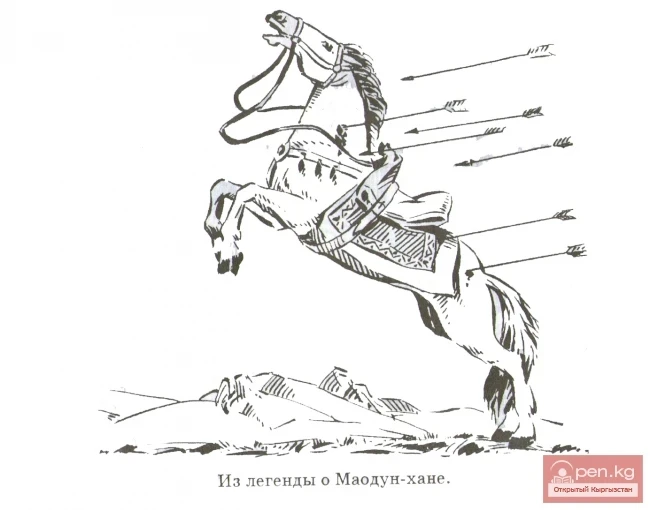

The word “Kyrgyz” is first mentioned alongside the name of the king of the Huns, Maodun-khan (Modé). According to a Chinese chronicle, in 201 BC, Maodun-khan sent a large army westward and captured the lands of the Gyanjun. Scholars have established that the Gyanjun were what the Chinese called the ancient Kyrgyz. The territory controlled by the Kyrgyz became known; it was located in the valley of the Manas River in Eastern Turkestan.

The deeds of Maodun-khan. The strengthening of the Huns is associated with the name of Maodun-khan. This is how the ancient Chinese referred to him. Turkic peoples in their legends respectfully call him Oghuz khan.

According to the oldest legend that has reached us, Maodun's father was the head of a small Hun tribe that inhabited the vast expanses in northern China. The khan did not like his elder son because of his willful and decisive character, so he gave him to a neighboring tribe as a pledge to prove that he wished to live with them in peace and harmony. After some time, the father realized that his son could be killed and decided to forcibly retrieve him. But Maodun outsmarted his treacherous father: stealing a steed, he returned home himself.

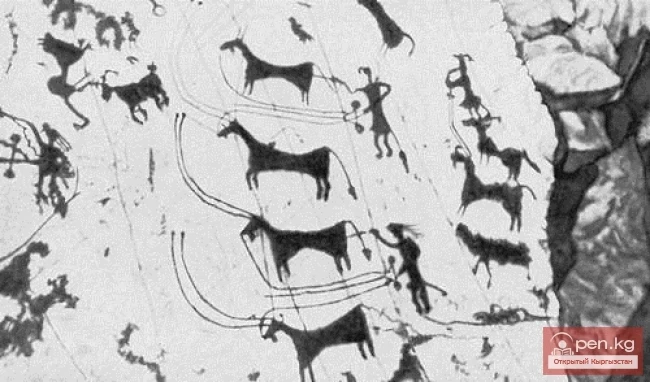

The tribesmen regarded the young man's act as a display of courage and supported him. To appease the people and atone for his guilt, the khan allocated a small cavalry unit to his son. Maodun took on their training. Clever from a young age, he invented a new arrow. The bone plates with holes located just behind the iron tip of the arrow emitted a terrifying, soul-chilling whistle in flight. Archaeologists have repeatedly found such arrows in the burials of nomads.

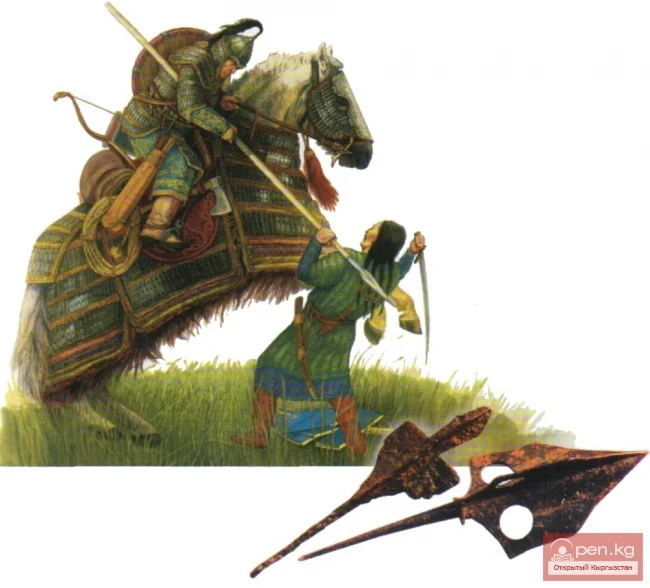

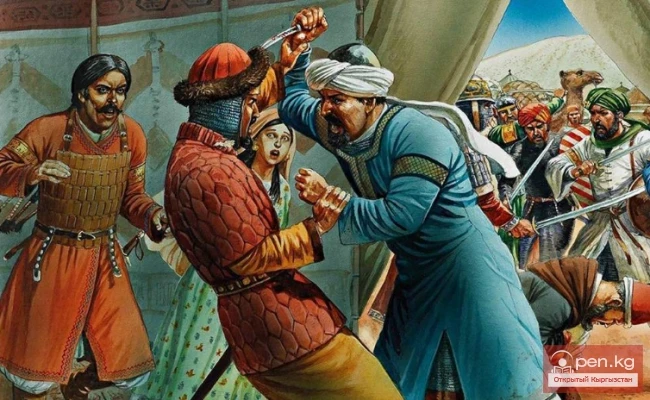

Maodun aimed to turn his subordinates into warriors who were excellent with weapons. Through exhausting training, he achieved, for example, that the warriors could instantly determine the direction of his arrow's flight and hit the target simultaneously with him. He demanded unquestioning obedience to his orders. Once, to test them, Maodun shot an arrow at his favorite steed, which had once rescued him from captivity. The horse, into whose body a hundred arrows simultaneously struck, fell dead. Several warriors refrained from shooting, considering it unnecessary to kill such a steed. Maodun immediately beheaded those who did not obey his will. On another occasion, he aimed an arrow at one of his wives. This time, no one dared to disobey. Maodun was very pleased: he was convinced that his will was law for them.

Once, during a hunt, Maodun coldly shot a whistling arrow straight into his father's back. In an instant, his body became covered with arrows, resembling a hedgehog. The old man fell lifeless, never realizing that his son had surpassed him in cruelty and treachery.

The beginning of the war. Chinese chroniclers report that this event occurred in 209 BC. The ruler of the neighboring Yuezhi (Tocharian) tribe sought a reason to quarrel with Maodun. He did not want to be associated with a leader who had killed his own father and sent a messenger to Maodun demanding that he choose the best stallion from the thousands of horses of the Huns and give it to him. The young khan gathered the leaders of the clans. They unanimously stated: “To such a shameless neighbor, not just a stallion, but even a simple horse should not be given.” Maodun listened to the wise elders and said: “For a good neighbor, a horse is not a pity,” — and gave one of the best stallions. The neighbors laughed at Maodun, and even within his own tribe, there was no shortage of condemnation.

But the neighbor did not calm down and sent another messenger, now demanding Maodun's beautiful wife. The furious advisors of the khan suggested declaring war immediately and washing away the insult with the blood of the shameless neighbor. Maodun again called the advisors to reason and, in the name of peace, gave his wife to the neighbor. His kinfolk despised him even more. For the third time, the neighbor requested lands close to the Huns. The advisors unanimously agreed: “This piece can be given away; grass does not grow there, and there is no water. Why would a nomad need such rocky land?” However, Maodun firmly disagreed: “I will never give away the land to anyone. The land is the foundation of the state.” And he issued two orders — to behead the advisors and to immediately set out on a campaign.

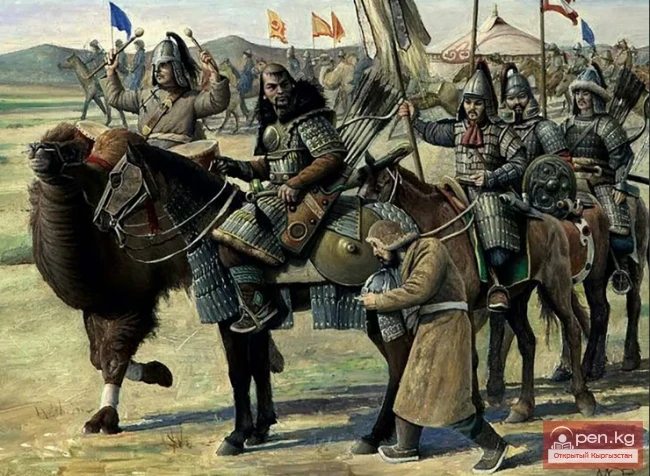

Like a flood, the Huns surged against the Yuezhi, defeated them, and drove them far to the west. Then it was the turn of others. From that time on, Maodun did not leave his horse; his whistling arrows instilled terror in the warriors of all the peoples of Central Asia. They bowed before the might of the Huns and submitted to them. In 201 BC, Maodun annexed the lands of the Kyrgyz, located in Eastern Turkestan, to his possessions. Maodun died in 174 BC. He conquered the peoples who freely lived on the territory from Transbaikalia to Tian Shan, from the Siberian taiga to the borders of China. Maodun did not manage to conquer only China. The empire fought the Huns for a long time. In the end, the Huns were defeated. The Yuezhi of Tian Shan also contributed to their defeat. Some of the Huns submitted to the victors, while others went west.

Read also:

The Era of the Great Migration of Peoples

NOMADS ARE HEADING WEST The concept of the "Great Migration of Peoples" was introduced...

Kara-Kyrgyz and Balasagun

Balasagun One of the capitals of the Karakhanid state was the city of Balasagun, located in the...

The Yenisei Kyrgyz in Antiquity

Kyrgyz-Gyangu The earliest mention of the Kyrgyz under the Chinese name “gyan-gun”, “heguni”, or...

Population of Kyrgyzstan from Ancient Times to the 6th Century

The first reliable traces of humans on the territory of Kyrgyzstan date back to the Paleolithic —...

Politics in Eastern Turkestan in the Late 50s-60s of the 18th Century.

The Defiance and Bravery of the Kyrgyz The ambitions of the Qing dynasty and their aggressive...

Ancient Kyrgyz in the 1st-2nd Centuries AD

Gyan-gun and Dinlins In the sources of the 1st-2nd centuries AD, the gyan-gun are not mentioned,...

Connection with the Information from Historical Sources about the Appearance of the Kyrgyz in the 9th-10th Centuries in the Territory of Modern Xinjiang

Facts Supporting the Statement of Prominent Soviet Ethnographer and Kyrgyz Scholar S. M. Abramzon...

The Population of Kyrgyzstan in the VI—XVIII Centuries

The ethnonyms “Turk” and “Turkut” were first mentioned in a Chinese chronicle from the year 546....

The Kingdom of the Karakhanids

The Karakhanid Kingdom...

Bulghachi, Dolony, Duglaty, Dukhutui

Bulghachi, Dolony, Duglaty, Dukhtui Bulghachi (bulghachi-dalkar, bulghachi-vilkar,...

Chagatai Khanate (13th Century)

Chagatai Chagatai declared his grandson Khara-Khulagu, son of Mutugen, as his heir. In 1241,...

Ancient Kyrgyz — the Earliest West Turkic Tribes

Ancient People — Kyrgyz The Kyrgyz, whose roots go deep into antiquity, lost in the darkness of...

Kyrgyz in the Mongolian Period

Usy, Han-Hena, and Yilanzhou In the "Yuan-Shi," in relation to the land of the Kyrgyz,...

"Central Asian" Kyrgyz

Kyrgyz Inhabitants of the Irtysh and Altai Regions? In this case, the area of "Kyrgyz"...

A new khan of the Kyrgyz has been elected in the Little Pamir

The new head of the Pamir Kyrgyz is 44 years old, named Azhybutu Abdylgani uulu. In Afghanistan,...

The State of the Yenisei Kyrgyz

Resettlement of the Kyrgyz to the Yenisei. The early medieval population of the Yenisei was...

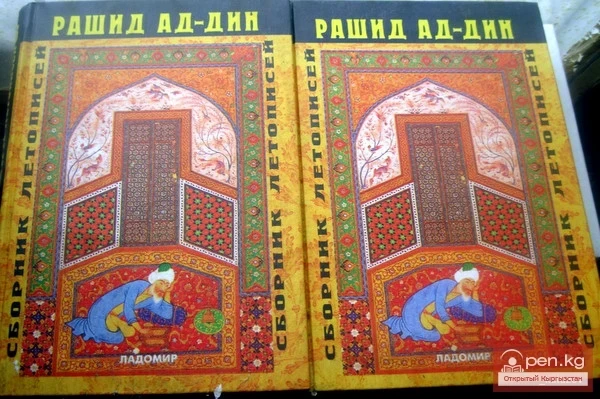

The Collection of Chronicles of Rashid ad-Din

Rashid ad-Din. Collection of Chronicles. Vol. I. M.-L., 1952 Rashid ad-Din (1247—1318) was the...

Muhammad Kyrgyz

The situation in Central Asia. In the early 16th century, feudal fragmentation intensified not...

The Entry of Kyrgyz into the Political Arena in Moghulistan

Said-Khan Against Muhammad-Kyrgyz In the early 16th century, the Kyrgyz entered the political...

"Baaryny, Baluki, Balikchi"

Baaryny (baarin, bayrin, bakhrin, naryn), balykchi (balikchi), baluki Baaryny (baarin, bayrin,...

The Religion of the Kyrgyz in Ancient Times

The foundation of marital and family relationships among the nomadic population of ancient...

The Last Years of Abdullah's Reign

The Last Campaigns of Abdullah The leader of the Khoshout omok, Galdama (son of...

Origins of Geographical Names

What science studies the origins of geographical names? Every person can easily list hundreds of...

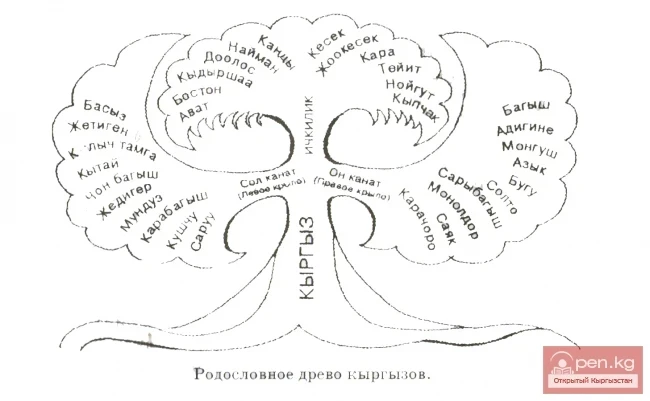

Genealogy of the Kyrgyz

Genealogy is the “tree of life” of a person. The Turks, including the Kyrgyz, who, due to their...

Karluks

Karluks...

Mogulistan from the period 906/1500–01 to 950/1543–44

Sheibani Khan, Mahmud Khan, Ahmed Khan, and Others... In 906/1500—01, Sheibani Khan, advised by...

"Talass Authority"

«Talas» beylik...

The Territory of the Kyrgyz from Ancient Times to the 6th Century

The Saka tribes were divided into three parts. In the southern regions of Kyrgyzstan lived the...

The Geopolitical Environment of the Kyrgyz in the 6th—18th Centuries

The Turkic states pursued an active foreign policy and participated in geopolitical games in the...

Aggressive-Expansionist Policy of Manchu-Qing China in Eastern Turkestan

Armed Resistance of the Kyrgyz Against Chinese Troops At the same time, Eastern Turkestan became...

Mogul-Uzbek Forces Against the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz

The Murder of Abd ar-Rashid's Son. Mahmud ibn Wali and Shah-Mahmud Churas, authors of the...

Great Khagan Ahmed

Ibrahim ibn Ahmed. This may refer to events related to the struggle of the great khan Ahmed, the...

Governance in Ancient Kyrgyzstan Before the 6th Century

Kyrgyzstan is one of the world’s centers of human emergence, statehood, and civilization. The life...

"Central Asian" Kyrgyz Nomads

Ulus Inga-Tyuri During military clashes, it appears that part of the "Central Asian"...

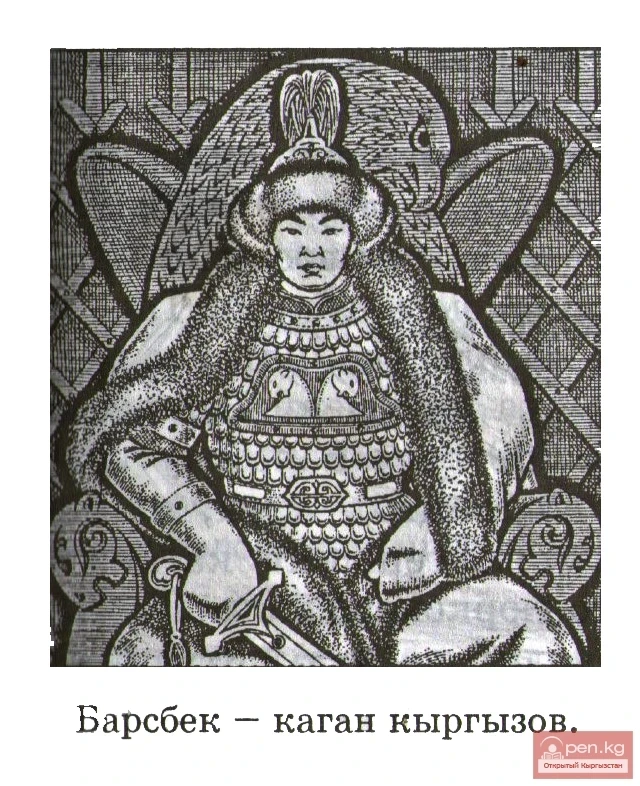

The Great Power of the Kyrgyz: Barsbek-Kagan

Kagan Barsbek. Central Asia at the end of the 7th century became the arena of significant...

Legends and Myths of the Kyrgyz

Writings of "Shajarat al-Atrak" In the anonymous work "Shajarat al-Atrak,"...

Alymbek - the Main Figure in the Khanate under Sha-Murad

The Removal of Malla-Khan by Alymbek Being a perceptive researcher, Duygamel, who closely observed...

Kyrgyz - Ancient Nomads

Kyrgyz - ancient nomads...

The Infiltration of the Yenisei Kyrgyz into the Tian Shan

The Infiltration of Yenisei Kyrgyz into the Tian Shan Our task is to examine the issues regarding...

The Joining of the Kyrgyz to Kokand in the Late 18th Century.

The Performance of Kyrgyz Tribes Against the Conquest Policy of Irdana. In the Sagymbaev version...

The title "Родник" translates to "Spring" in English.

Spring Once upon a time, in ancient times, after fierce battles with invaders, during a period of...

Choros, Suldus, Tatars, Turkmen, Uyghurs, Minalagi, Nuygut, Ordabegi

Minlaga, Noyguts, Suldus, Tatars, Turkmen, Uyghurs, Ordabegi, Churasi Minlaga (Minalaga) — their...

"Progenitor" of the Kyrgyz Ethnicity of the 12th Century

Ibrahim ibn Ahmed and Anal-Hakk Thus, the "progenitor" of the Kyrgyz ethnicity of the...

Iskak Hasan Uulu Pulat-Khan

Mulla-Iskak Asan oglu After the Battle of Khanabad, the Kyrgyz of the Adygine tribe, who were...

Turkic Khaganates

In Central Asia, the Great Turkic Khaganate (552-744 years) emerges. The Turks considered Ashina,...

Sultan Said, Takhir-Khan and Others...

Sultan Said and Tahir-khan In 1520, Rashid-Sultan raided the Kalmyks, killed their prince named...

Was the emergence of the future Alai Queen in the close circle of the political elite of Kokand accidental?

The Struggle for Power Among the Political Elite of Kokand So, was the emergence of the future...

Population of Kyrgyzstan as of January 1, 2013

Population of Kyrgyzstan Thanks to the fundamental changes that occurred in Kyrgyzstan after the...