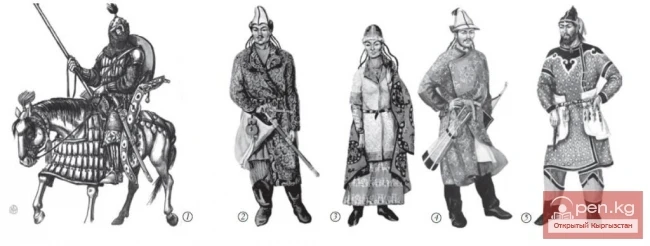

M.G. Volkova writes: “The emergence of the term ‘Circassian’, whose ethnic nature is indicated by the Turkic environment, was associated with certain political events of the 13th century... (M.G. Volkova ‘Ethnonyms and Tribal Names of the North Caucasus’, Moscow, 1974, pp. 21, 23). In Russian chronicles, the ethnonym ‘Cherkassy’ is only associated with Turkic tribes that served in the principalities. They are better known by the names: ‘black cloaks’, ‘berenids’, ‘kovuys’. Later, the term ‘Cherkassy’ became established as one of the ethnonyms of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. It should be noted that the primary core of this people consisted of the chronicled ‘black cloaks’. According to N.M. Karamzin, N.I. Berezin, P.P. Ivanov, and I.A. Samchevsky, the ‘black cloaks’ are called ‘Circassians’. Therefore, this ethnonym was used as a general name for the medieval Pecheneg-Oghuz tribes: Torks, Uzes, Pechenegs, black cloaks, Berenids, Kovuys, and Polovtsians. Prof. N.A. Aristov wrote: “It can be suspected that the ethnonym ‘Circassian’ was brought to the foothills of the Caucasus by a union of Turkic tribes.” The ethnonym ‘Circassian’ has a rather ancient origin, and its area of distribution is quite broad from Altai to the Danube, where the Adyghe peoples did not live at all. The antiquity and deep connection of the ethnonym ‘Circassian’ with Turkic peoples is confirmed by excerpts from the works of well-known scholars K.Ya. Grot and D. Ilovaisky. I.F. Blamberg wrote back in 1834: “Circassians..., whom Europeans incorrectly call, call themselves Adyga or Adyhe.” This was also noted by G.Yu. Klapot: “Circassian is of Tatar origin and is composed of the words ‘cher’ - road and ‘kesmek’ - to cut.” Summarizing these facts, it is quite obvious that the ethnogenesis of the Kabardians involved the Turkic tribe of Circassians (Western Kazakhs), who later became the feudal lords of the Kabardians. T. Lapinsky wrote about this: “In this brief overview of the history of the Circassians, I want to refute the misconception that is prevalent throughout Europe. It is completely incorrect when the peoples of the Caucasus, Abazins (Adyghe), as well as the Dagestani tribes, are designated by the name of Circassians. There is no longer a Circassian people; the remnants of it in the Caucasus no longer call themselves that and are disappearing more and more day by day...” “These Circassians still form a distinct tribe, Ezden-Tlako, and marry only among themselves; therefore, the Tatar race has remained almost pure among them” (p. 101). Here is how Lapinsky describes the appearance of the Circassian prince and his son, with whom he was personally acquainted: “Stout with a silver beard, he was one of the most beautiful elders I have ever seen. His facial features had a clear imprint of a dignified Tatar, and among 1000 Abazins (Adyghe), he could be instantly recognized as a foreigner, just like his son Karabatyr Ibrahim, who by appearance was a copy of his father... The retinue also consisted almost exclusively of Turks, Tatars, and several Circassian warriors” (p. 289). Theophil Lapinsky lived among the Adyghe for a long time but considered the Circassians a Turkic alien tribe that had dissolved into the Adyghe environment: “I always distinguish the Circassians, who in Abkhazia (Adygea) are viewed as unwelcome guests, from the Abazins and Adyghe, who are the owners of the land and make up the main mass of the population” (p. 163). In Kazakhstan, where part of the Kazakhs of the Junior Juz and Alabug Tatars still call themselves Circassians. Convincing confirmation of this is found in the “Genealogy of the Turks, Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, and Khan Dynasties” by author Shakarim Kudaiberdi-ulu. He writes: “Circassians are part of the Junior Juz of the Kazakh people” (cited work, p. 68). More precise information was discovered in the work of the well-known historian Academician V.V. Radlov: “Circassians - a subdivision of the Kazakhs-Kyrgyz of the Small Horde, the Alachin tribe” (cited work, pp. 75, 113, 287). This fact was also noted by T. Lapinsky in the 18th century, the genetic connection of the Circassians with the Kazakh people: “Circassians are called a tribe in the middle horde of the Kyrgyz, which during their winter migrations usually settles on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea” (cited work, p. 72). It has been established that the historical prototype of Inal was a real representative of the Khazar administration, performing the functions of the western viceroy of the kagan. Moreover, it is important to note that, according to oral tradition, Inal's activities date back to the 7th-8th centuries (“150 years after Muhammad”). In genealogies, Inal's father is named Khruvataya or Khurpataya, who has a khan lineage and connections with the Byzantine emperor... According to the genealogy provided by P.S. Pallas, Inal had two sons who bore the names Komuk (according to Y. Klapot) and Kazi. From the first descended the princes of the Small Kabarda, and from the second - the Big Kabarda [5].” I agree that the term “Circassians” was not always used in relation to the Adyghe, and that not all those mentioned in historical documents as Circassians (Cherkasy, Sherkess, etc.) are Adyghe. This conclusion can be drawn from the first part of your post, which goes up to the phrase: “Summarizing these facts, it is quite obvious that the ethnogenesis of the Kabardians involved the Turkic tribe of Circassians (Western Kazakhs), who later became the feudal lords of the Kabardians.”

***Who are the Circassians

“Not knowing one’s essence, a person does not understand their needs. The same goes for peoples.”

H. Mamai

Historical science is based on facts, while conclusions drawn in the absence of facts are hypotheses and myths. Unfounded conclusions only highlight their vulnerability and inadequacy. In the impenetrable depths of the centuries, it is very difficult to discern the traces of the movements of tribes and peoples, especially the Turks. The history of the Turkic mercenaries, the Mamluks, is difficult to localize territorially, as Turkic tribes at different times served as a mediating link between the West and the East. To restore the truth, irrefutable evidence is needed: data from linguistics, onomastics, ethnonymics, literature, and architecture. As is known, a people or nation is primarily defined based on a commonality of language, territory, socio-economic life, and psychological makeup, manifested in the commonality of the culture of the ethnicity.

It seems that everything is clear and understandable, all known chronologies of Mamluk dynasties and states created by Turkic mercenary warriors from India to Egypt are presented, examples of the involvement of Turkic guards by Byzantium, Persia, China, Russian principalities, Georgia, Bulgaria, Hungary, and the Arab Caliphate - all this is confirmed by historical data from medieval chronicles. But there are also opposing opinions on this issue, and we must come to a unified opinion. The author of the book “Circassian Mamluks” S.H. Khatho writes the following: “In general, the anthroponymic factor occupies a key place in the process of identifying the ethnic affiliation of a particular Mamluk. Thus, if we encounter names in the chronicles such as Barsbay, Bibars, Jakmak, Kait, Kansav, Biberd, etc., it is completely obvious to a researcher familiar with Caucasian anthroponymy that the bearers of these names are Circassians.” (p. 50).

The description of Bibars’ appearance also does not correspond to the Asian type of Kipchaks; Mamluk chroniclers used the term “Turk” in relation to Circassian sultans as a more general concept (p. 51).

Sultans Bibars and Kalaun are considered Kipchaks, despite the fact that the Burj tribe never existed (referring to S. Zakirov) (p. 51).

The name Bibars is Circassian - Pyiperes.

In the Kipchak steppes, anyone could be born, not just a Kipchak.

Circassian, emir of the hundred Ozdemir al-Hadis. He galloped off with several warriors to the Mongols, shouting that they surrendered to the mercy of Mengu-Timur. Approaching the Tatar-Mongols, he said that he wanted to convey something important to their leader (p. 68).

Circassians preserved their language, and many of them barely spoke Arabic (p. 155).

The Kosož prince Rededya had his own coat of arms. Let’s provide several quotes from another of his books “Circassian (Adyghe) Rulers of Egypt and Syria in the 13th-18th centuries.”

Apparently, the Nart name Sosruko, encountered by Ibn-Iyasa in the form of Sosruk, is the first written evidence of the existence of this name in the Circassian environment. (p. 11).

The military immigration of Circassians to Kievan Rus continued until the Mongol wars. It creates the impression that all or almost all military specialists in the service of Russian princes from the 11th to the 14th centuries were Circassians, Abazins, and Ossetians. The number of Slavic-Adyghe names is by no means limited to the provided list: Nechevich (cf. Naguch; Doman (cf. Domanuka)); Kozarin (cf. Kazhar) Kerebet; Domash Tverdislavich (or. Tomash, Tomashuk); Melik Semyon (cf. Malek'we Semen); Olbyr Shershevich; Bayandyuk (cf. Bayantyk'o); Varazko Miyuzovich, etc. (p. 38).

The anthroponymic factor has a different significance. So, let’s turn to the names of the Burjii princes: Anas - Ienës; Beshtak - Beshtek'o; Katmosa - Kaimes; Sauk - Shaauk'o; Yaroslanopa - Arslanipa (Arslan is an Alan name, and ipa is a suffix in Abkhaz and Abazin meaning “son”); Baste - Baste (Baste is a surname among the Shapsugs); Selu - Zaluk (a surname among Kabardians); Uruzoba - Uruz-ipa; Aluk - Aleko (alek'o); Asen - as name; Altunopa - Altun-ipa (a Turkic name, Abazin suffix; Asaduk; Tomzak; Kurtok; Osaluk; Tarsuk - (p. 133) Alan (ass) and Turkic names with Circassian endings. The very name of the tribe is distinctly present in the widely used surname among the Adyghe, Byrj. (p. 43).

The last ruler of the Byrj, pshi Bachman, died in 1241 along with his allies, the Circassian pshi (prince) Taukar and the Ass Kachiruko-Ale (p. 49).

The motives for Tamerlane's campaign in Circassia were largely subjective and personal: it was revenge for Circassian raids in Khorezm (p. 50).

Significant interest is presented by the data of General A. Rigelman, who wrote that the Don Cossacks of his time unanimously claimed that they descended from the Circassians. (p. 59).

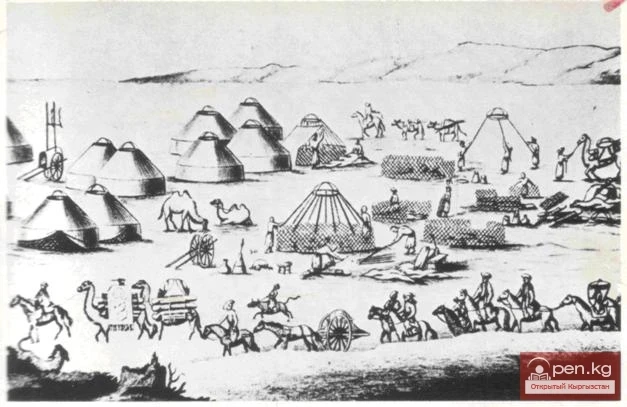

Ethnographic details brought by the Circassians to Ukraine include the form and technology of housing; heating the dwelling with kizyak; heavy wooden plows, the presence of Circassian saddles among the Zaporozhians; the custom of shaving the head while leaving a tuft of hair on the crown; the fabric “Cherkessina,” from which the former Ukrainian clothing was sewn; headgear and Circassian kaftans. (p. 59).

The term “Pasha” (pashé) is clearly borrowed by the Ottoman Turks from the Adyghe. It is possible that the first pashas of the Ottomans were among the Mamluks. The Ottoman rulers themselves were vassals of the Circassian sultans and, in this regard, could widely utilize Circassian military experience (p. 61).

In the medieval history of Crimea, Circassians appear quite often. The Armenian historian of Crimea, Ter-Abramyan, in his book lists the following settlements and areas associated with Circassian presence: the village of Cherkes, Cherkes-Eli, Cherkes Togoy, Cherkes kosh, Cherkes tyuz, Cherkes kermen.

P.S. Pallas also notes another toponym associated with Circassian presence on the peninsula, the upper part of the Belybek River named Kabarda. (p. 69).

Mamluks karanis, i.e., veteran Mamluks. And although it is quite clear that experienced warrior-veterans are meant by karanis, the etymology of the word itself has not been clarified. (p. 99).

Circassians are designated in Mamluk sources as Jarkas or Jarkasi. There are also alternative transcriptions: Charkas, Sharkas, or Sharkasia (p. 108).

Turkic Mamluks of Egypt diminished in number so much that all that remained of them consisted of a handful of surviving veterans and children. National solidarity and the monopolistic dominance of the Circassians were expressed in the use in contemporary sources of the terms “people” (al-qawm), nation (al-jans), tribe (al-ta, ifa) exclusively in reference to the Circassians. (p. 111).

Emir Alan-Karadja began his career as a page and squire to Sultan Qaitbay. The family name, nickname - ibn Karadja, indicates that this Mamluk came from the princely Ossetian clan Karadzauti. In May 1509, he was sent as an ambassador to the Ottoman Sultan.