For a proper understanding of the ethnic processes that led to the formation of the Kyrgyz nationality, the interpretation of the question regarding the ethnonym "Kyrgyz" holds significant importance. Without delving into the history and etymology of this ethnonym and the related ethnonym "Burut," associated with the Kyrgyz, it is necessary to express a few thoughts on its ethnic content. It is hardly acceptable (as some researchers have done in the past and still do) to treat the ethnonym "Kyrgyz" as having the same ethnic content throughout its existence.

The greatest difficulty in addressing this question lies in the fact that the bearers of the ethnonym "Kyrgyz" (at least in the 16th-17th centuries) lived simultaneously in Southern Siberia, Eastern Turkestan, the Tian Shan, Pamir-Alai, Central Asia, and the Kazakh steppes, in the Ural region (among the Bashkirs), i.e., in territories that were quite distant from each other. This fact alone indicates that the ethnic history of the Kyrgyz represented a long, multifaceted process closely linked to the history of the formation of many other tribes and peoples in both Central and South Asia and neighboring regions. Taken in isolation, without specific ethnic content, outside the surrounding ethnocultural environment, and without considering chronology, the name of the nationality hardly serves as a starting point for in-depth research. Researchers have repeatedly noted that the mere existence of similarly sounding ethnonyms in extremely distant territories does not provide a sufficiently strong argument in favor of asserting the common origin of their bearers.

The question of the relationship between modern Kyrgyz of the Tian Shan and Pamir-Alai and the Kyrgyz of the so-called Kyrgyz statehood of the 9th-10th centuries, as well as the question of the era of the formation of the Kyrgyz nationality, belongs to the category of the most complex issues, which continue to be debated and discussed, with opposing viewpoints existing. Attempts to establish a straightforward connection between the Kyrgyz of the Tian Shan and Pamir-Alai, on one hand, and the Kyrgyz of the Yenisei, on the other, based mainly on the coincidence of names, have not yielded any significant results and have not become a basis for a scientific solution to the problem of the origin of the Kyrgyz people. However, in a number of works until recently, the ethnonym "Kyrgyz" along with its bearers was considered as something that moved in an unchanged form, both in time and space. The Kyrgyz of the 7th-8th centuries, as well as those of the 18th-19th centuries, were approached as a homogeneous ethnic collective, a single ethnic community. The levels of development of productive forces, different political conditions, different geographical environments, different production relations, and various ethnic surroundings were insufficiently taken into account when discussing the Kyrgyz on the Yenisei and the Kyrgyz in the Tian Shan.

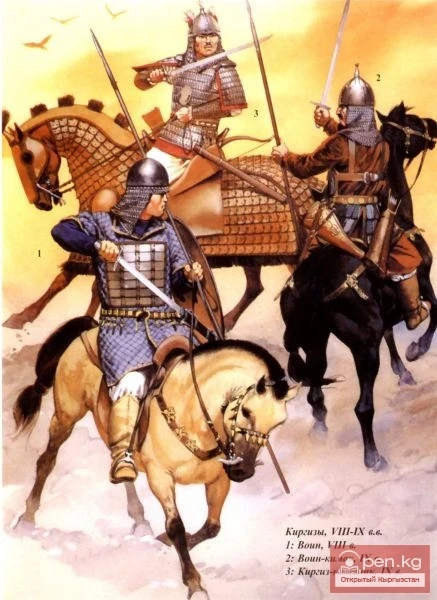

But how can we explain the fact that the name "Kyrgyz" "moved" from the upper reaches of the Yenisei far to the southwest, all the way to Ura-Tyube, to the Afghan Badakhshan? And what was hidden under this name at the end of the first millennium of our era: a political union, an administrative-territorial or military-nomadic association of tribes, or a formed nationality with its self-designation? Even if we fully trust the sources about the existence at that time (9th-10th centuries) of Kyrgyz statehood, it must still be attributed to early feudal statehood, where tribal traditions prevailed. The tribes that were part of this union-state could not help but retain their ethnonyms and their tribal self-consciousness. Therefore, it is difficult to agree with the opinion of some scholars that by the 9th-10th centuries there existed a fully formed nationality with the self-designation "Kyrgyz." The objective conditions for the emergence of a nationality had not yet matured at that time (see below), and socio-economic development had not yet reached the level at which an independent nationality could be formed. It is well known that the formation of almost all Turkic-speaking nationalities in Central Asia and Kazakhstan closely coincided in time. There are no grounds to assume that the Kyrgyz constituted any exception in this regard, although the formation of the Kyrgyz nationality undoubtedly possessed distinctive features.

However, are we not making a mistake by recognizing that the name "Kyrgyz" has always been equivalent to the ethnonym? Neither runic inscriptions, nor the testimonies of Mahmud Kashgari in his "Divan," nor the "Collection of Chronicles" by Rashid ad-Din, nor other sources provide convincing evidence that the term "Kyrgyz" was an ethnonym. V. P. Yudin is entirely correct when he writes: "It seems that in explaining the origin of the Kyrgyz people, one should abandon the desire to follow the term, which has already become the main accepted point of view regarding the Kazakhs."

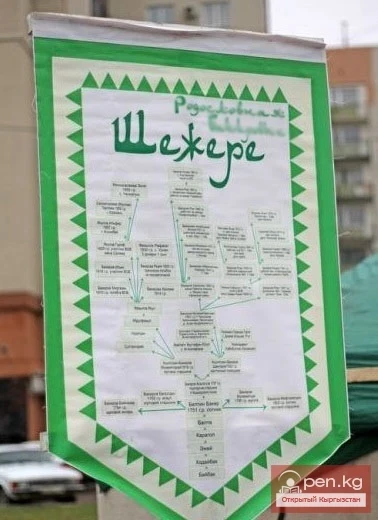

It is likely that the formation of the Kyrgyz nationality as a specific historical stage of ethnic community was much more complex. No one "adopted" the name "Kyrgyz"; it gradually established itself as an ethnic self-designation during the course of historical development and the formation of the Kyrgyz ethnos. It was not long ago that the self-designation "Kyrgyz" was necessarily accompanied by the name of the tribe to which a particular individual identified themselves.

In the early 20th century, even the small groups of Kyrgyz, far removed in the mountains of Kuen-Lun and cut off from the main mass of Kyrgyz, who called themselves Kipchaks, simultaneously identified themselves as Kyrgyz. Therefore, ethnic self-consciousness had already solidified. It can be assumed that in the distant past, a number of tribal groups, for various reasons and at different times separated from their "core," retained a clear understanding of their political unity while also maintaining their common name and tribal names.

The name "Kyrgyz" in earlier stages of history, especially during the era of the greatly exaggerated Kyrgyz "great power," had, in our opinion, not so much an ethnic as a political content. It was applied to groups of tribes of various origins living not only in the Minusinsk Basin and within the Sayan-Altaic region but also significantly further south and southwest, in the territory of Dzungaria and partially Eastern Turkestan. Sources from the 10th century confidently speak of the southern border of the Kyrgyz passing through Eastern Turkestan. Consequently, some tribes of Central Asian origin, which neighbors referred to as Kyrgyz (the self-designations of these tribes are unknown), lived near the modern territory of the settlement of the Kyrgyz, and in some places, these territories even coincided.

It is hardly necessary to speak of the resettlement of any large mass of Kyrgyz from the Yenisei, if a certain part of the Kyrgyz tribes only needed to move a few hundred kilometers from the northeast and east to the Western Tian Shan, and then further south, to find themselves on the territory of the modern Kyrgyz settlement. The materials available to researchers provide grounds to assume that the territory of modern Kyrgyzstan was predominantly populated not by Kyrgyz living on the Yenisei, but by some, mainly Turkic-speaking, tribes that previously lived within Eastern Pre-Tian Shan, partly in the Irtysh and Altai regions. For many of them, the name "Kyrgyz" was initially not an ethnonym but a designation of the political union to which they belonged.

Approaching this complex issue dialectically, it should be noted that if before the 10th-11th centuries the geographical distribution of the name "Kyrgyz" was significantly broader than the ethnic core for which this name was an ethnic self-designation, then after the 10th-11th centuries, on the contrary, the circle of tribes involved in the process of Kyrgyz ethnogenesis was significantly broader than the territory directly associated with the ethnonym "Kyrgyz." The mistake of some researchers lay in their search for the Kyrgyz only where the proper name "Kyrgyz" was found. It seemed to possess a magical power that compelled researchers to obediently follow it. Ethnic groups that were outside this name were regarded as having no relation to Kyrgyz ethnogenesis.

It is now completely clear that this problem must be approached concretely-historically, i.e., taking into account all those tribes and ethnic groups that could have participated in the formation of the Kyrgyz nationality. However, the formation of the Kyrgyz nationality itself required a number of conditions: a) the presence of a relatively stable territory, sufficiently ensuring communication between tribes; b) the existence of a dominant common language among all major tribes; c) the presence of an economic system that combines the leading economic structure with other forms of economic activity; d) the proximity of cultural and everyday characteristics that developed through exchange and cultural-historical interaction, fostering a certain inclination among individual tribes towards each other in a specific historical context; e) the presence of similar features in ideological views and elements of a common cult; f) the presence of socio-political factors uniting a group of these tribes into an alliance or confederation based on their relations with other neighboring peoples and tribes; g) the consciousness of belonging to a new, broader ethnic community — nationality.

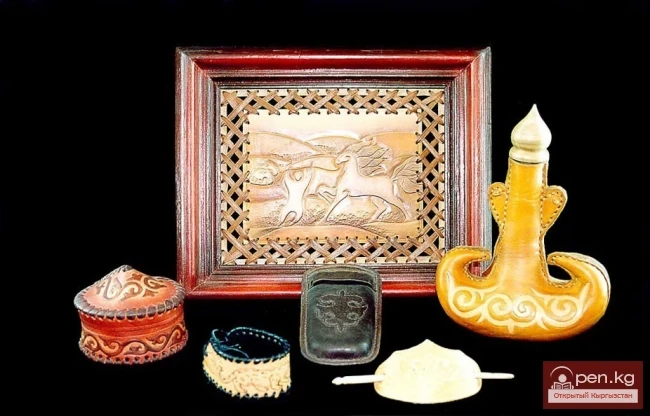

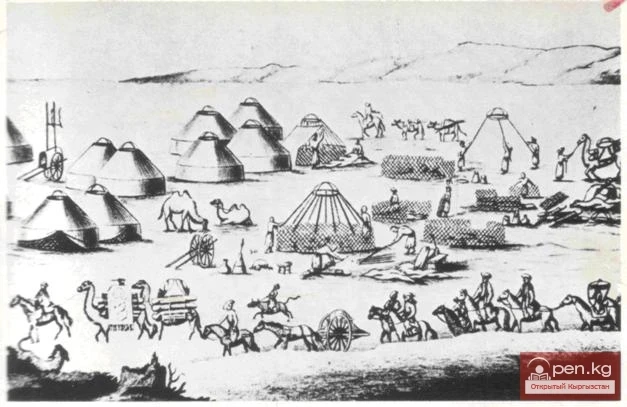

All these conditions were present. The tribes that formed the Kyrgyz nationality already had a common territory in the Middle Ages, and there existed a single language (with tribal dialects). All these tribes were already developing a common ethnic self-consciousness. They led a nomadic lifestyle, engaged in livestock breeding and hunting, and lived under patriarchal-clan customs and patriarchal-feudal social relations; they developed a common type of culture, although it retained local and tribal features. From tribal epics, a unified national epic monument "Manas" began to form. Finally, the aggressive aspirations of the Oirat feudal lords contributed to the consolidation of territorially close and largely related tribes into a single socio-political entity.

The aforementioned conditions, although each to a varying degree, ultimately ensured the formation of the Kyrgyz nationality. The beginning of this complex process can be attributed to approximately the 14th-15th centuries, but it undoubtedly progressed most intensively in the 16th-17th centuries. The completion of the process of forming the Kyrgyz nationality, by all indications, occurred in the 18th century, although in some areas this process continued partially even later. In any case, in the period preceding the incorporation of Kyrgyzstan into Russia, the Kyrgyz already represented a fully formed large nationality.

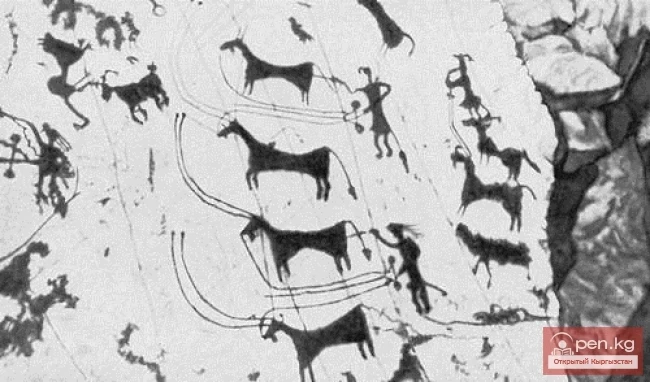

The Kyrgyz archaeological-ethnographic expedition of 1953-1955, supplemented by evidence from historical sources, allows us to answer with a considerable degree of accuracy the question about the main ethnic components that formed the Kyrgyz nationality in the form that presents itself to us in the 16th-19th centuries.