Monuments of History and Culture of Kyrgyzstan of the 18th—19th Centuries

The historical and cultural monuments of Kyrgyzstan from the 18th to 19th centuries did not arise in a vacuum; their roots go deep into the past, reflecting the centuries-old history of the people.

Historical and cultural monuments cannot be considered outside the context of the general historical background and the socio-economic situation of the local population at that specific time. The issues of political and socio-economic history of Kyrgyzstan in the late 18th to 19th centuries have already been sufficiently developed in Soviet historiography. They trace deep ancient traditions of the Kyrgyz people and the local origins of many of its elements. The examination of fortifications and cult architecture, as well as folk and mining crafts, and decorative applied arts allows us to conclude that the material culture of the Kyrgyz people has its origins in antiquity and the Middle Ages, naturally continuing the cultural traditions of numerous nomads who lived at different times on the territory of Kyrgyzstan—from the Saka, Usun, and Huns to the Turks and Mongols. At the same time, it contains a number of elements that bring it closer to the culture of the peoples of Central Asia. All of this convincingly indicates that the Kyrgyz ethnicity formed precisely in the Tian Shan mountains based on the autochthonous local tribes and tribal unions, which came into contact with and sometimes assimilated with tribes of Central Asian and Southern Siberian origin, from where the very ethnonym "Kyrgyz" was introduced, acquiring a broader ethnopolitical significance.

The material culture of the Kyrgyz people was distinctly influenced by the nomadic lifestyle and patriarchal domestic structure. Overall, in its main features, it was deeply original and unified across the entire territory inhabited by the Kyrgyz, although certain local peculiarities were present. A special examination of fortifications shows that their construction, although it intensified with the Kokand colonization in the late 18th to early 19th centuries, was by no means solely a result of it (as was believed quite recently). Recent expeditionary work and a more careful reading of archival materials and other primary sources convincingly demonstrate, firstly, that there were already fortifications in Kyrgyzstan before the Kokand fortresses, and secondly, that Kyrgyz fortresses (albeit smaller in size) existed alongside the Kokand ones, serving as residences for the Kyrgyz feudal nobility.

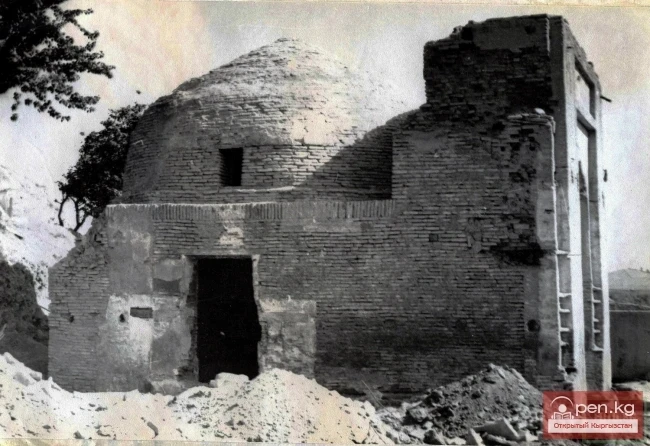

The construction of cult architecture was, on one hand, an endeavor independent of the Kokand rulers (the construction of traditional Kyrgyz burial mausoleums—gumbazes), and on the other hand, it was stimulated and even forcibly imposed by the Kokand rulers to spread and consolidate Islam in the nomadic environment of the Kyrgyz (mosques and madrasas). And while gumbazes were a widespread phenomenon throughout Kyrgyzstan, having only minor local variations, mosques and madrasas during the Kokand period were found only in the southern regions of Kyrgyzstan, closest to the Islamic centers of the khanate, while in the central regions of the Tian Shan and northern Kyrgyzstan, they were completely absent: Islam had not yet deeply rooted itself here.

The folk applied and decorative arts, housing, and clothing of the Kyrgyz people were distinctive, and the peculiarities of their habitat—the high mountain ranges of the Tian Shan—determined the local population's engagement in mining crafts.

Due to the absence of its own written literature and historical chronicles among the Kyrgyz people before the revolution, information about all this is drawn from folklore and the monumental heroic epic "Manas," as well as from Eastern narrative sources in Uzbek, Tajik, and Chinese languages. However, a certain type of source has survived, represented by material monuments—these are fortifications, architectural and cult structures, and objects of material culture that help recreate vivid pictures of the historical and cultural past of the Kyrgyz people.

One might ask: is it worth studying the Kokand fortresses, which served the purposes of suppressing the Kyrgyz population, and the mosques and madrasas that were instruments of spiritual enslavement of the local population by Islam?

It is indisputable that the monuments of fortification and cult architecture that arose and existed during the feudal period served the interests of the ruling class. They catered to khans, feudal lords, and the Muslim clergy, and often belonged to representatives of the exploiting nobility—which is generally characteristic of all unjust, class-based societies. Nevertheless, this does not exclude or diminish their historical and cultural significance as monuments of the past. They were built by the labor of ordinary people, embodying the centuries-old experience of folk craftsmen and artisans, the manifestation of reason and talent, and the spirit of the people.

While admiring the mausoleum "Gur-e Amir" and other burial sites of the feudal nobility in Samarkand, we often do not even think about or know those in whose honor they were erected. But we cannot help but bow before the labor and exquisite artistry of those simple craftsmen from the people, whose names history has not preserved, yet they themselves have maintained an unshakeable memory of themselves through majestic architectural ensembles. And the gumbaz of "Manas" attracts us not as the burial site of the obscure Kanizek-khatun—the daughter of emir Abuki—but as an architectural monument associated by the people with the memory of their hero—the defender Manas, as a creation of the popular genius.

The Kokand fortresses were a testament to the freedom-loving spirit of the Kyrgyz people, who successfully fought against the khan's oppression and the despotism of local feudal lords (otherwise, why would the conquerors have built these fortresses?). The ruined walls and towers of the fortress walls are not just clay walls and collapsed blocks—they are the result of the struggle of the Kyrgyz people against the invaders, memorial sites of our ancestors' battles for freedom and independence.

The cult structures—madrasas and mosques, which existed during the period of Kokand rule only in southern Kyrgyzstan and did not spread to the northern regions—also testify to the degree of spread and resistance to Islam among the Kyrgyz population. Created and adorned by folk architects, they represent a page in the art and architecture of the people. They reflect the artistic tastes of the people, sometimes even in contrast to the orthodox canons of Islam, which stands out as a strong point.

However, it should be remembered that despite the significance of the monuments of the past, on one hand, we should not forget that they speak of khans and feudal lords, serving as carriers of religious delusion; on the other hand, we should not fall into extremes and idealize all cultural heritage, especially in attempts to idealize the role of Islamic and other cult institutions in the development of folk culture. We should not get carried away by purely professional assessments in the promotion of monuments, nor forget the role, for example, of cult monuments in the ideological struggle of the past and present, taking into account their ideological content, utilitarian-practical orientation, and functional purpose.

All this indicates that we must approach the evaluation of ancient monuments differentially, as relics of their time, and we should neither diminish nor idealize their significance. But what truly constitutes the cultural heritage of the people requires constant study, careful attention, and widespread promotion, for "only a system that has no future does not value either the past or the present."

Every nation wants to say as much about itself as possible not only in the present but also in the past..."

"...And the past life will again arise before the eyes of the living."

Read also:

Types of Higher Plants Listed in the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985)

Species of higher plants removed from the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985) Species of...

Omuraliyev Ashymkan

Omuraliyev Ashymkan (1928), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1975), Professor (1977) Kyrgyz. Born in...

Types of Insects Listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS Not Included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan

Insect species listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS, not included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan 1....

Kenesariyev Tashmanbet

Kenesariyev Tashmanbet (1949), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1998), Professor (2000) Kyrgyz. Born...

Chorotegin (Choroev) Tynchtykbek Kadyrmambetovich

Chorotegin (Choroев) Tynchtykbek Kadyrmambetovich (1959), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1998),...

Zheenaly Sheriev

Sheriev Zheenaly (1932-2002), Candidate of Philological Sciences (1970), Professor (1991) Kyrgyz....

Zhorobekov Zholbors

Zhorobekov Zholbors (1948), Doctor of Political Sciences (1997) Kyrgyz. Born in the village of...

Prose Writer, Critic Dairbek Kazakbaev

Prose writer and critic D. Kazakbaev was born on June 20, 1940, in the village of Dzhan-Talap,...

Prose Writer, Journalist Djapar Saatov

Prose writer, journalist Dzh. Saatov was born on February 15, 1930, in the village of Alchaluu,...

Tourist Area Management Program

The project "USAID Business Development Initiative" (BGI), within the tourism...

The title translates to "Poet Soviet Urmambetov."

Poet S. Urmambetov was born on March 12, 1934, in the village of Toru-Aigyr, Issyk-Kul District,...

Poet, Critic, Literary Scholar Omor Sooronov

Poet, critic, literary scholar O. Sooronov was born in the village of Gologon in the Bazar-Kurgan...

Atkurova Altynai Razbaevna

Attykurova Altynai Razbaevna Art historian. Born on November 23, 1973, in the village of Gulcha,...

The Poet Gulsaira Momunova

Poet G. Momunova was born in the village of Ken-Aral in the Leninpol district of the Talas region...

Poet, Prose Writer Tash Miyashev

Poet and prose writer T. Miyashev was born in the village of Papai in the Karasuu district of the...

Poet, Linguist Kasym Tynystanov

Poet and linguist K. Tynystanov was born on September 9, 1901—November 6, 1938, in the village of...

Poet, Prose Writer Medetbek Seitaliev

Poet and prose writer M. Seitaliev was born in the village of Uch-Emchek in the Talas district of...

The Poet Kubanych Akaev

Poet K. Akaev was born on November 7, 1919—May 19, 1982, in the village of Kyzyl-Suu, Kemin...

Literary scholar, prose writer, poet Dzaki Tashtemirov

Literary scholar, prose writer, poet Dz. Tashtemirov was born on October 15, 1913—October 7, 1988,...

The Poet Baidilda Sarnogoev

Poet B. Sarnogoev was born on January 14, 1932, in the village of Budenovka, Talas District, Talas...

Critic, Literary Scholar Abdyldazhan Akmataliev

Critic and literary scholar A. Akmataliev was born on January 15, 1956, in the city of Naryn,...

The Poet Subayilda Abdykadyrov

Poet S. Abdykadyrova was born in the village of Sary-Bulak in the Kalinin district of the Kirghiz...

Poet, Art Historian Sarman Asanbekov

Poet and art critic S. Asanbekov was born in the village of Aral in the Talas region of Kyrgyzstan...

Poet Karymshak Tashbaev

Poet K. Tashbaev was born in the village of Shyrkyratma in the Soviet district of the Osh region...

Poet, Playwright Raikan Shukurbeков

Poet and playwright R. Shukurbeikov was born in 1913 and passed away on May 23, 1964, in the...

Zakirov Saparbek

Zakir Saparbek (1931-2001), Candidate of Philological Sciences (1962), Professor (1993) Kyrgyz....

Critic, Literary Scholar Bibi Kerimdzhanova

Critic, literary scholar B. Kerimdzhanova was born on October 30, 1920, in the village of...

Types of Insects Excluded from the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan

Insect species excluded from the Red Data Book of Kyrgyzstan Insect species excluded from the Red...

Kerimzhanova Bubu Dyikanbaevna

Kerimjanova Bubu Dyikanbaevna (1920-1993), Candidate of Philological Sciences, Corresponding...

Prose Writer Kachkynbay (KYRGYZBAI) Osmonaliev

Prose writer K. Osmonaliev was born on March 5, 1929, in the village of Chayek, Jumgal district,...

Poet Abdilda Belekov

Poet A. Belekov was born on February 1, 1928, in the village of Korumdu, Issyk-Kul District,...

Salamatov Zholdon

Salamatov Zholdon (1932), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (1995), Professor (1993)...

Critic, Literary Scholar, Poet Kachkynbai Artykbaev

Critic, literary scholar, poet K. Artykbaev was born in the village of Keper-Aryk in the Moscow...

Poet, Prose Writer Isabek Isakov

Poet and prose writer I. Isakov was born on September 1, 1933, in the village of Kochkorka,...

The Poet Akbar Toktakunov

Poet A. Toktakunov was born in the village of Chym-Korgon in the Kemin district of the Kyrgyz SSR...

The Poet Tenti Adysheva

Poet T. Adysheva was born in 1920 and passed away on April 19, 1984, in the village of...

Poet Akynbek Kuruchbekov

Poet A. Kuruchbekov was born on December 5, 1922 — November 29, 1988, in the village of Eryktu,...

Bazarbai Shamsi (1937)

Bazarbaev Shamshi (1937), Doctor of Philosophy (1993), Professor (1995). Kyrgyz. Born in the...

Poet Dzhaparkul Alybaev

Poet Dzh. Alybaev was born on October 12, 1933, in the village of Birikken, Chui region of the...

Poet, Prose Writer Mar Aliev

Poet and prose writer M. Aliev was born on July 14, 1932, in the village of Kochkorka, Kochkorka...

Oskyon Dzhusupbekovich Osmonov

Oskon Osmonov Jusupbekovich (1954), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1994), Professor (1996) Kyrgyz....

The Poet Sooronbay Jusuyev

Poet S. Dzhusuev was born in the wintering place Kyzyl-Dzhar in the current Soviet district of the...

Karymshakov Rakhym Karymshakovich

Karymshakov Rakhym Karymshakovich (1936), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (1995),...

Poet, storyteller-manaschi Urkash Mambetaliev

Poet, storyteller-manaschi U. Mambetaliev was born on March 8, 1934, in the village of Taldy-Suu,...

The Poet Jumakan Tynymseitov

The poet J. Tynymseitova was born on 11. 1929—29. 07. 1975 in the village of On-Archa in the...

Poet Abdravit Berdibaev

Poet A. Berdibaev was born on 9. 1916—24. 06. 1980 in the village of Maltabar, Moscow District,...