Historical Sources on Kyrgyz Musical Folklore

Curl error: Operation timed out after 120001 milliseconds with 0 bytes received

Curl error: Operation timed out after 120001 milliseconds with 0 bytes received

In the music for choor, sybyzgy, and other wind instruments, there is a special figurative sphere that is hard to imagine without in the national culture. It provides a sense of the eternity of existence and a mood of calm contemplation. Furthermore, wind instruments traditionally carry practical functions, serving the labor, daily life, and leisure of the Kyrgyz people. The oldest types of wind instruments, preserved to this day in certain samples, refer us to the "primordial

One of the oldest and most widespread types of Kyrgyz folk instrumental music is the kyuu for the temir ooz komuz (or temir komuz) and zhygach ooz komuz. The modest arsenal of expressive means of these instruments is compensated in the kyuu by the figurative-thematic relief and unique timbre variety.

One of the ancient layers of Kyrgyz instrumental music in the oral tradition is associated with the kyl kyak. It clearly lags behind the komuz in popularity among both performers and listeners. It is indicative that at the first All-Kyrgyz Olympiad of Folk Musical Creativity, held in the capital of the republic in 1936, out of thirteen instrumentalists, ten played the komuz, two played the temir komuz, and only one played the kyl kyak. Nevertheless, this instrument, along with the genres

In Kyrgyzstan, several regional performing schools have developed, each with distinctive stylistic features. In the 20th century, they found their leaders in the form of famous komuz players. The performance style of the Issyk-Kul musicians, "led" by Arstanbek, Murataaly, and Karamoldo, is characterized by philosophical depth and strict style. The komuz players of the Osh school have managed to preserve the ancient, archaic traditions of performance, represented honorably by

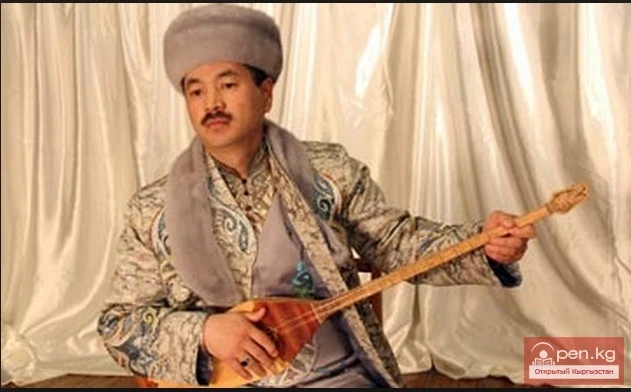

Komuz is the most popular and beloved musical instrument of the Kyrgyz people. In ancient times, the komuz was played in almost every Kyrgyz yurt, and in the 20th century, it made its way to the grand concert stage. Kyrgyz komuz players perform abroad, drawing the attention of a wide audience and specialists to the unique sound of the instrument and the distinctive genres of komuz kyuu.

The genres of Kyrgyz folk instrumental music have historically developed as specific functional systems, possessing certain properties common with the vocal genre hierarchy. These include belonging to the mass or professional sphere of creativity, to a specific type of artistic activity (public performance, ritual, play, cult act, etc.), and to a particular type of figurative content. At the same time, the genre system of the instrumental tradition has its own specifics.

The folk music of the Kyrgyz has developed over centuries. The traditions of oral folk art remain strong to this day. Kyrgyz folklore vividly and expressively reflects almost all aspects of nomadic life, historical events, and the relationships of the Kyrgyz with their surrounding environment. Modern folk groups in Kyrgyzstan, drawing on such rich material, have many opportunities for creative development.

As is known, the category of self-sounding instruments (idiophones) includes all sound-producing devices in which the source of vibrations is the body itself or part of it, rather than a string, membrane, or column of air enclosed in a channel. In Kyrgyz musical culture, this includes the so-called mouth (lip) komuz of several types, as well as instruments like jingles, bells, rattles, etc.

Kyrgyz folk percussion instruments form a small group. The arsenal of folk percussion instruments consists of three membranophones: dobulbash (in northern Kyrgyzstan — dobulbas), dool, and karsyldak. These instruments are carriers of rhythm, one of the strongest means of artistic influence on humans and animals.

The oldest instruments, which are wind instruments, were primarily given practical significance by the Kyrgyz. They performed signaling functions (calling people to public events, moving herds of livestock), and only later artistic, aesthetic functions (rest, entertainment). In ancient times, instruments of this group were included in ensembles during military battles. The epic "Manas" mentions performers on wind instruments, whose playing made a significant emotional impression on

Kyrgyz folk instruments are an essential part of the national artistic culture — both as attributes of musical creativity and as creations of applied art. In modern society, they function in various aspects and situations. They are played solo, as well as in ensembles and orchestras, during home music-making and at public concerts. Music schools, studios, and secondary and higher educational institutions introduce children and youth to instrumental performance or provide opportunities to

The creativity of the akyns has been studied since the early years of the establishment of national philology and musicology. For the first time, works of specific akyn genres were recorded by A. Zataevich. His first folklore collection (250 Kyrgyz instrumental pieces and melodies. — Moscow, 1934) contained three musical examples, two of which (No. 120 and 121) were recorded from T. Satylganov. In the second collection, prepared in 1936 but not published during the scholar's lifetime,

Based on their talent and mastery, akyins are divided into two main categories. The first category includes major improvisational akyins (tekme chots akyn, zalkar akyn). The second category consists of akyins whose improvisational skills are not as developed; they prepare their performances in advance (zhattama mayda akyn, jamakchy akyn). There is also an intermediate level: akyins occupying this level are referred to as "orto," meaning "medium." With focused and systematic

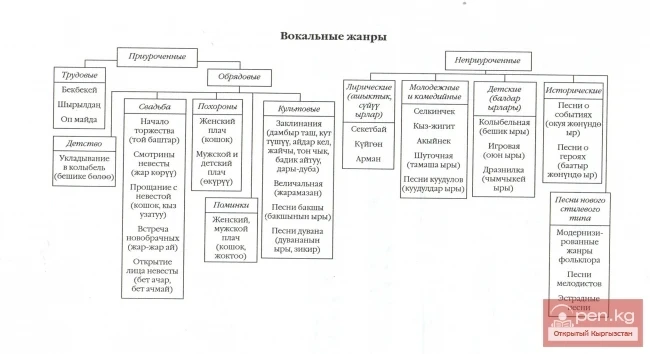

Dialogical Akyn Genres — a professional artistic form of song and poetic competitions with the general name kayym, widely spread among the people. The youth song genres "kız-jigit," "akıynek," and friendly song and poetic tournaments "sarmerden," among others, are built on the type of competitive dialogue.

In solo genres, the akyn sings or recites their own or borrowed text, accompanying themselves on the komuz or kyl kyak. In these genres, akyns of various levels and styles perform, and it serves as a specific school for novice akyns to refine their performance style. Furthermore, solo genres of akyn creativity allow the author to concentrate the listeners' attention on what personally concerns them, showcasing their creative individuality.

Akyn Creativity is a unique layer of Kyrgyz song tradition. Its significance is determined by the diverse functions performed by the carriers of this remarkable form of folk artistic creativity within national culture. The activities of akyns are the best indicator of a careful attitude toward cultural heritage. This is a living and timeless art that contains a powerful intellectual force.

The Kyrgyz epic is a professional form of oral folk musical and poetic creativity. In the epic, the richness of the people's worldview and artistic reflection of the surrounding reality is manifested more fully and vividly than in other genres. The epic captures global categories of social existence and consciousness: history, religion, material and artistic culture, and the mentality of the Kyrgyz.

Kyrgyz Folk and Mass Musical Creativity In Kyrgyz folk and mass musical creativity, songs about historical figures and events have hardly developed as an independent genre. History was widely covered in both large and small epics, but the images of legendary leaders and heroes were presented in a generalized-mythological manner. Real historical figures — such as khans Shabdan and Ormon, datkas Kurmanjan and Alymbek, heroes Balbai and Kozhomkul — more often became the subjects of akyn songs

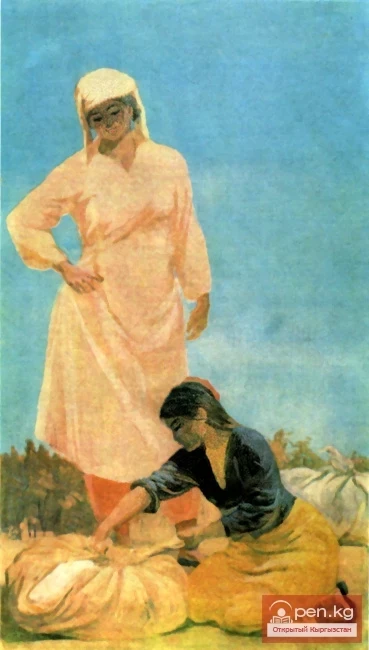

The theme of the first feature films about Kyrgyzstan, made before the war by Uzbek ("Covered Wagon," 1927) and Russian ("Aigul," 1936) filmmakers, is the slave-like, dependent position of women and their subsequent liberation.

Before 1917, there was no film production in Kyrgyzstan. To highlight the life of the peoples of Central Asia, the "Vostokkino" association was established, and the first film stories and films about Kyrgyzstan began to be released in the late 1920s. Cinematographers from Moscow came to the republic to shoot the life of the Kyrgyz people. The founder of Soviet geographical cinema, V. Shneiderov, filmed travel films "At the Foot of Death" (1928) and "At an Altitude of

The melodies of this genre group are differentiated into children's songs and songs for children. Some are created and performed by children themselves, while others are created by adults.

The Kyrgyz youth song genres include songs performed by young men (jigitter yrlary) and young women (kyzdar yrlary) aged approximately 14 to 25 years. This is the most dynamic layer of folklore culture, characterized by specific socio-psychological and artistic-aesthetic features determined by the age of the performers and listeners, the emotional mobility of their psyche, the optimism in their perception of the world, and the multifacetedness of their interests.

The genres of song lyricism are richly represented in Kyrgyz folk art, being among the most widespread, developed, and popular. Despite the variety of content, these genres share many commonalities, which give them stylistic unity and emotional kinship. Often, the same melody—“obon”—“migrates” from one lyrical song to another and is performed with new lyrics. For instance, the tune of “Oh, dear girl” (“Oy, asyl kyz”) is almost exactly used in the songs “Tea” and “To the collective farm friend”

Curl error: Operation timed out after 120001 milliseconds with 0 bytes received

In pre-class and class societies, when the ancient Turkic-speaking ancestors of the Kyrgyz lived a nomadic pastoral life, song folklore was inseparable from their labor activities.

The vocal creativity of the Kyrgyz people reflects their rich history, social and domestic relationships, spiritual and labor experiences. Song accompanies the Kyrgyz constantly and daily, and the love for singing has a truly mass character. The vocal culture of the oral tradition has formed, developed, and improved over thousands of years, resulting in its artistic-expressive and logical-constructive principles and means.

Curl error: Operation timed out after 120001 milliseconds with 0 bytes received

The concept of folk music (traditional music, musical folklore) is relative in its genesis. It emerged only when, in the process of societal evolution and its artistic culture, highly professional forms of individual creativity developed, gaining the status of academic art. In European countries, these forms were established by a number of social institutions, including specialized educational establishments (conservatories, academies). From the need to relate these professional and

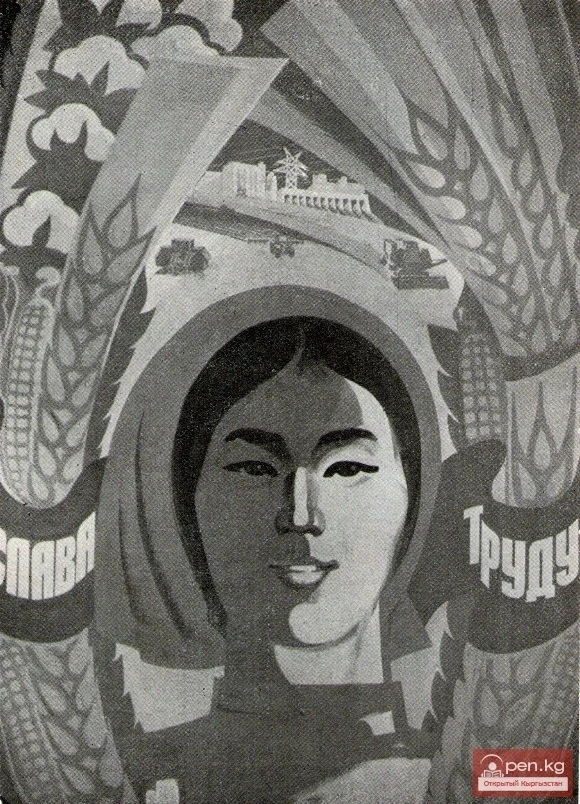

Monumental forms of art in Kyrgyzstan during the 1960s to 1980s emerged at the forefront of artistic life and actively participated in the formation of a harmonious personality of the era of developed socialism, addressing the pressing issue of environmental aestheticization. With the increasing pace of scientific and technological progress during this period, all types of ideological and educational work among the masses were mobilized, and a significant place was allocated to monumental

A. Solovyev works exclusively in medals, having grown over a decade into an experienced medal artist with serious thematic interests and an individual plastic language. From his early works of a narrative, sometimes illustrative nature, and from experiments with form influenced by modern, often contradictory searches in the field of small plastic forms, he has arrived at a strict style. His more recent medals, which are typically traditionally rounded and small in size, are substantive,

The small form of the medal today, alongside psychological depth and strictness of form, is also characterized by features of monumentalism, poster-like sharpness of thought, and bright decorativeness. All these tendencies, with their positive and negative aspects, are to some extent inherent in the developing medal art of Kyrgyzstan. Going beyond the realm of commemorative and anniversary medals, Kyrgyz medal artists widely explore a variety of themes, employing modern techniques, plastic

Medal Art. In the 1970s, medal art began to develop in Kyrgyzstan. The first enthusiasts in this field, Vyacheslav Viktorovich Kopotev and Anatoly Nikolaevich Solovyov, graduated from the Frunze Art School and mastered the laws and expressive means of this specific type of small plastic art over several years. The growing interest in medal art began in foreign and Soviet art as early as the 1960s, and in the 1970s and 1980s, this traditional branch of chamber sculpture, having received

The Union of Photojournalists was established in early 2007 as a creative collective of photographers working in the genre of reportage photography in Central Asia and beyond. Today, the Union of Photojournalists is an interregional public organization – a creative union that brings together photojournalists and specialists from various fields of photography and journalism.

Expressive genre sheets were created by S. Chokmorov ("Men Sitting," 1964), A. Ostashev ("Shashlyk," 1969), D. Jumabaev ("By the Water," 1972; "In the Room," 1972; "Gray Day," 1972), N. Evdokimov ("Dance of Steel," 1972), T. Kurmanov ("Shepherd's Children," 1981), A. Biymyrzaev ("Girl Against the Frame," 1982), Ya. Solop ("Portrait of Dzhamankulova A.," 1983; "Rest," 1983), N. Imanalieva

The watercolor creativity of A. Mikhalev, M. Omorkulov, and R. Nudel has "created a solid foundation for the development of diverse artistic personalities of the subsequent generation. The uniqueness of Kyrgyz nature, new features in the life of our republic, the heroism and romance of everyday labor, the beauty of man, the charm of his spiritual world — these are the themes of watercolor artists. In their works, they strive to find original solutions, utilizing the multifaceted nature of

Years of hard work were devoted to the watercolors of R. Nudel. His watercolors "are mainly painted from life, yet they are compositional due to the constructive clarity of forms, plastic and color integrity." He was one of the first in Kyrgyzstan to master the techniques of modern watercolor painting on wet paper, which produces effects of saturation and density of color. A well-known cycle of his from the 1960s consists of sheets painted during a trip to Uzbekistan ("Khiva.

U. Akhunov, a master of architectural and industrial landscapes, a singer of the city of Osh, has entered the history of Kyrgyz watercolor. He combines a lyrical talent with a striving for documentary accuracy and portrait-like representation. He created a series of watercolors dedicated to the monuments of medieval architecture in Central Asia (1966), depicting already disappearing cult and civil structures. In a large number of watercolors, Akhunov captured the life of the city of Osh in the

Primarily as a watercolorist, the graphic artist M. Omorkulov has developed, who, like A. Mikhalev, is close to the traditional, airy-transparent manner of painting. Working almost exclusively from nature, Omorkulov travels extensively throughout the republic. His works reflect the rhythm of modern life in Kyrgyzstan with its agriculture, new constructions, and most importantly — the people. Omorkulov is one of the few watercolorists in Kyrgyzstan who shows a persistent interest in the

During the period under consideration, watercolor has been enriched with new trends, which "in Kyrgyzstan develops in line with the visual arts of the republic, which has formed as a realistic school, primarily striving for a figurative understanding of nature, having as its ideal the expression of the artist's idea and intention in a plastically clear, cohesive form." The truthful depiction of reality, conditioned by the realistic method of creativity, lies at the heart of the

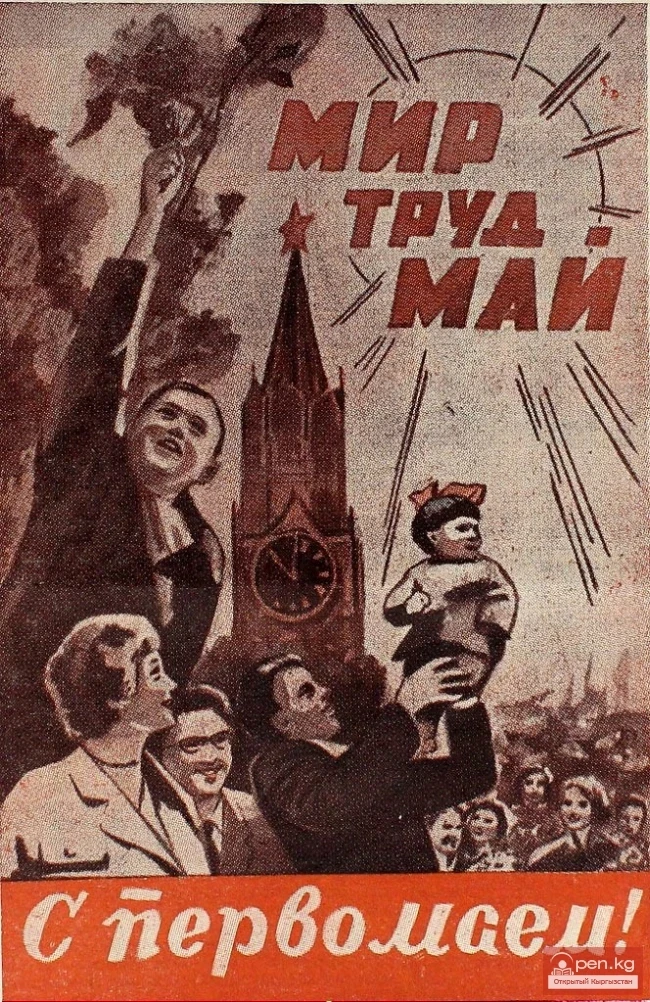

Currently, all varieties of poster art are actively developing and improving in Kyrgyzstan, but the leading type remains the political poster, particularly emphasizing the theme of the struggle for peace. This theme is addressed from various aspects — both through the positive image of the fighter for people's right to life and through the exposure of the inhumane essence of militarism. The increased ideological and artistic level of Kyrgyz posters is confirmed by the active participation

In recent years, poster artists M. Sultanaliev ("Glory to the Motherland," 1982; "Kurpsay HPP — Under Construction!," 1982; "Glory to the Heroes of Kyrgyzstan," 1985), A. Asyamov ("Olympic Moscow," 1982; "Vitamins for Europe," 1983), A. Tsyganok ("American Boomerang," 1985; "Your Labor, My Labor — For the Party, For the Motherland," 1983), S. Tokoev ("My Labor — For You, Motherland," 1983), and N. Akmatov (in

The poster artists of the country who graduated from art universities, such as U. Omurov, M. Sultanaliyev, A. Asyamov, A. Tsyganok, and others, actively shape their own themes and individual styles, with their creative paths beginning at the turn of the 70s and 80s. Their focus is on the pressing issues of the time. They celebrate the beauty of the everyday heroism of Soviet workers who are implementing the grand program for the further development of Soviet society put forth by the party,

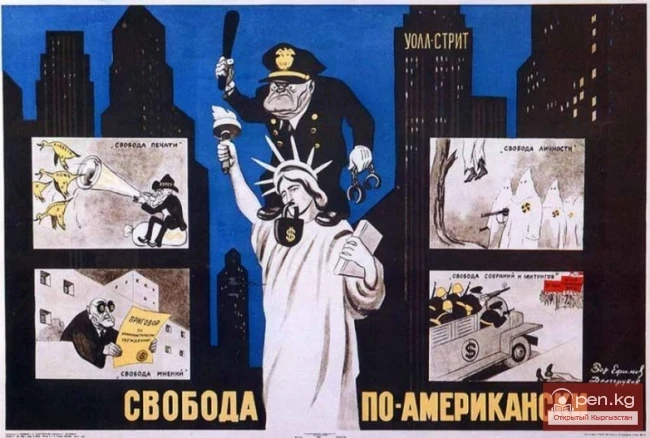

As satirical poster artists with a gift for observation, psychological accuracy in characterizing satirical figures, and their own distinctive style, V. Zhukov, A. Turumbekov, and M. Tomilov developed their craft in the 70s and 80s, representing Kyrgyz posters at republican, nationwide, and international exhibitions. Zhukov's posters are characterized by sarcasm in revealing the remaining shortcomings of everyday life, a lack of overload in compositional and color solutions, and a

In recent years, the experienced poster master F. Zubakhin has been actively working. In political posters, he developed ideas of worldview, moral, and patriotic education of the masses — “May Day — Day of Solidarity of Workers” (1972); “50 Years of the Kyrgyz SSR” (1974); “On Guard for Peace” (1974); “The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics is the state of workers and peasants” (1976); “Leninism — the banner of millions” (1977); “I Serve the Soviet Union” (1977); “Glory to the Leninist

In the 1970s and 1980s, with a trend of steadily increasing ideological and artistic levels of visual agitation, political posters became increasingly widespread. During this period, their role in the development of political and labor activity among the masses, in ideological struggle and the movement for peace, in organizing socialist competition, implementing the party's agrarian policy, spreading patriotic initiatives, strengthening production discipline, and promoting the

In the 1960s, A. Turumbekov successfully made his mark in poster art, working extensively as a master of satirical magazine drawing. His political posters from 1969, "Freedom," "Voice of America," "Junta," and "American-style Freedom," were awarded a Silver Medal at the International Exhibition "Satire in the Struggle for Peace" (Moscow, Leningrad, Sofia, 1969). They are characterized by sharp satirical focus, expressiveness of grotesque means,

In the system of any visual art, the poster occupies an important place, sharply responding to the social moods of the time, experiencing a surge during periods of restructuring life, nationwide struggle, or creation. This art, accessible to all, is intended to mobilize the people for necessary public actions, and it was the first to develop in the history of visual arts in Kyrgyzstan, attracting the attention of graphic artists and painters. It began to strengthen in the 1960s with the