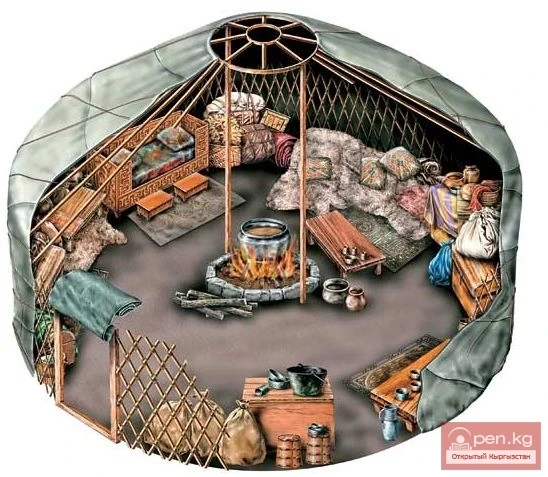

Domes and Mazars — burial mausoleums of the Kyrgyz — have their origins in the domestic architecture of earlier times. This architecture has almost not survived, but it existed. It belonged to a people who later became purely nomadic. These monuments are also the most significant evidence of the local nomadic population's involvement in agriculture, mining, and trade in the distant past. Over time, the original forms of the domes evolved, acquiring features of the typical dwelling of nomads — the yurt, elements of which can be traced in all Kyrgyz domes without exception.

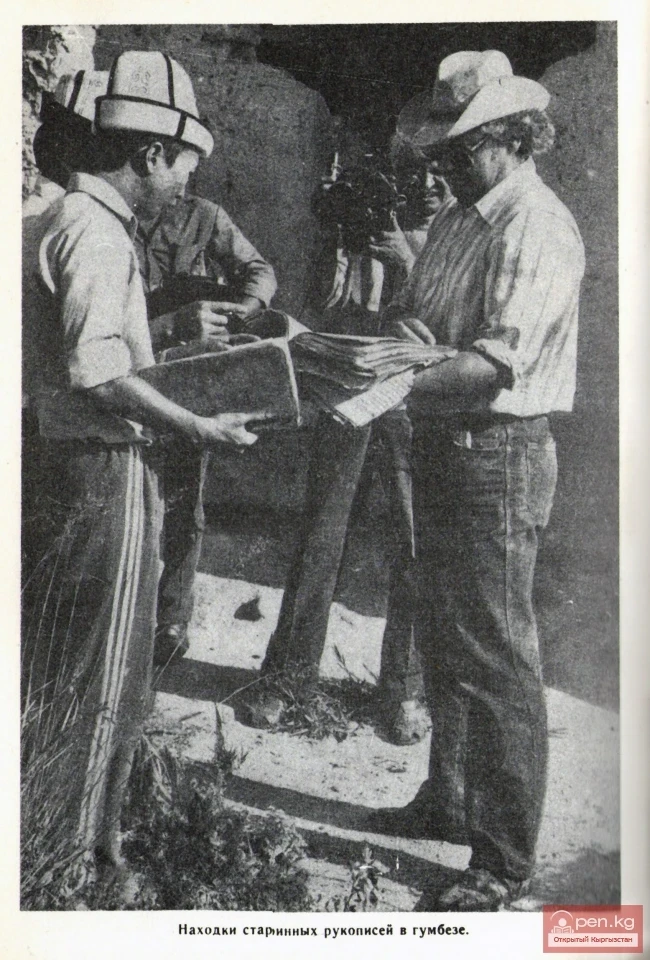

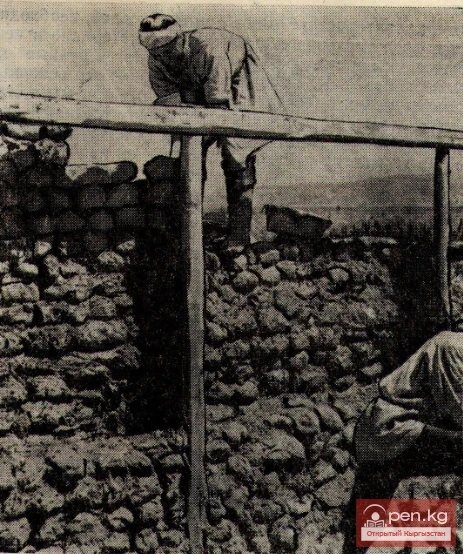

Background. A distinctive feature of monuments from the 16th to 19th centuries is their poor preservation. Kyrgyzstan's archaeology knows many monuments from earlier times and the Middle Ages that are better preserved, while later monuments made of adobe bricks or rammed earth walls (duvals) have almost completely deteriorated. An understanding of them can only be formed by combining field excavation methods with source analysis of preserved archival documents, as well as drawings by travelers and topographers from reconnaissance military-scientific expeditions of the last century.

Naturally, the question arises, what is the purpose and difference between a dome and a mazar? A dome is a typical burial structure built from adobe or burnt bricks, ranging in shape from a small stepped sagana — a gravestone — to a large mausoleum with a powerful portal adorned with decorative niches or intricate brickwork. A mazar, on the other hand, is considered a burial structure, a tree, or some water source that is or was a place of worship for believers. Not every mausoleum can be called a mazar, so this term is only applicable to the names of burial structures associated with the names of "saints" by the faithful.

Kyrgyz domes, their architecture, and the associated folklore have not yet been subjected to special study. However, archaeologists, historians, and architects have recorded these monuments whenever possible and tried to describe them. If we adhere to chronology, we should mention the famous Kazakh scholar Ch. Ch. Valikhanov, Russian travelers P. P. Semenov and M. I. Venyukov, the well-known Soviet archaeologist A. N. Bernshtein, architect V. E. Nusov, and historian V. M. Ploskih. They expressed many different viewpoints in their evaluations of such monuments; however, all these researchers noted the deep folk traditions and the rich internal content infused into them by skilled masters — historical, archaeological, architectural, art historical, etc.

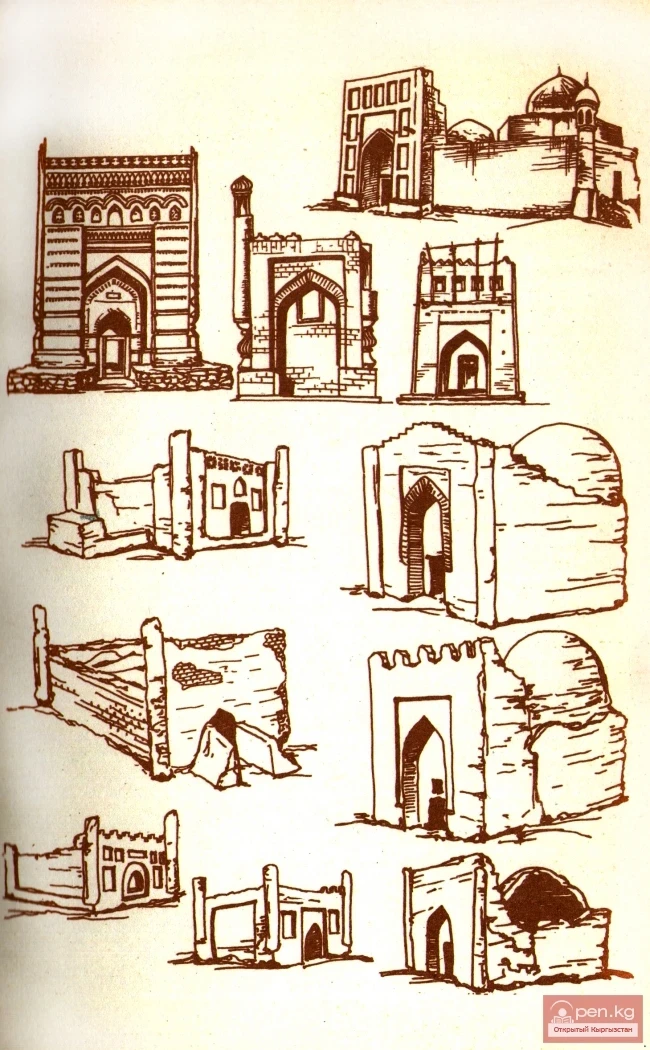

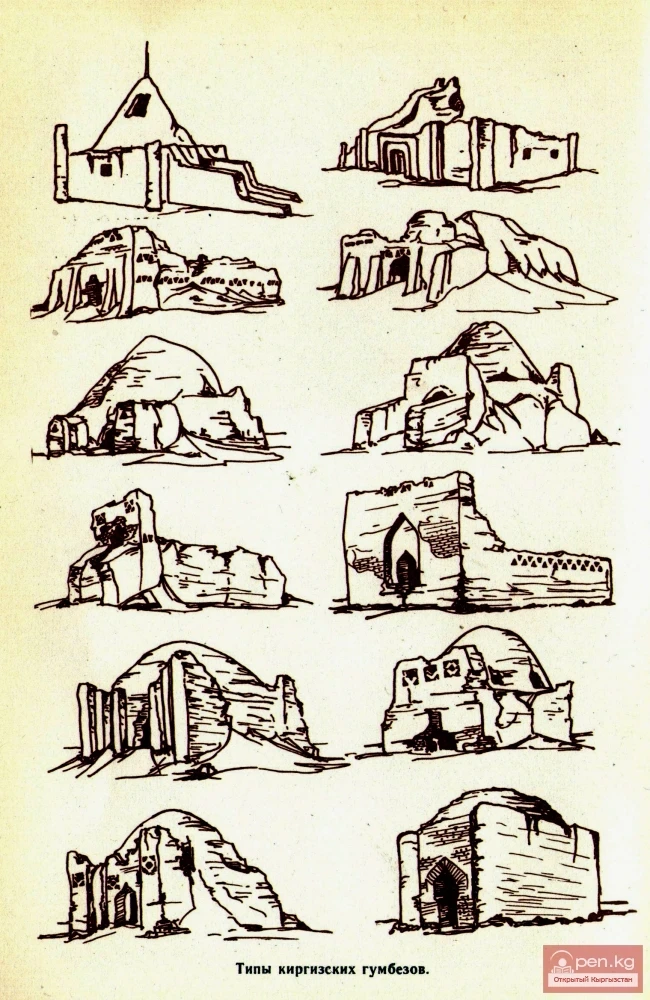

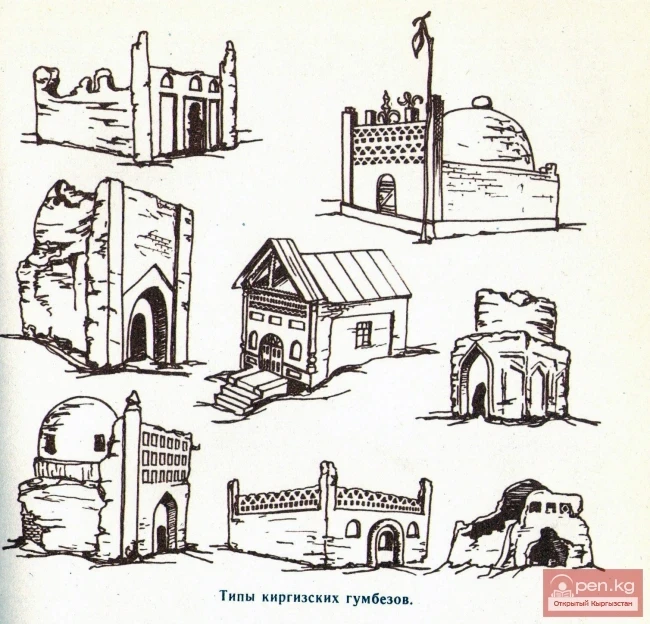

Types of Kyrgyz domes

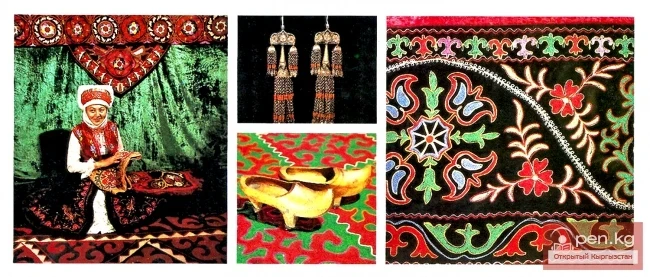

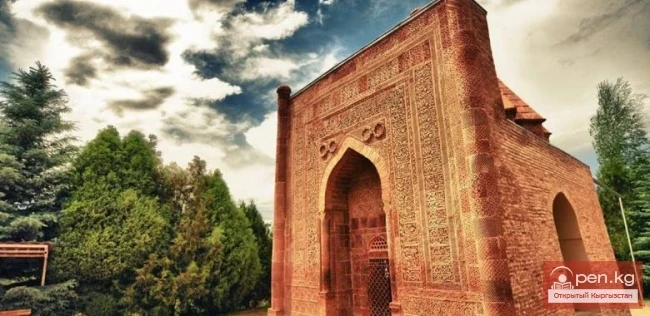

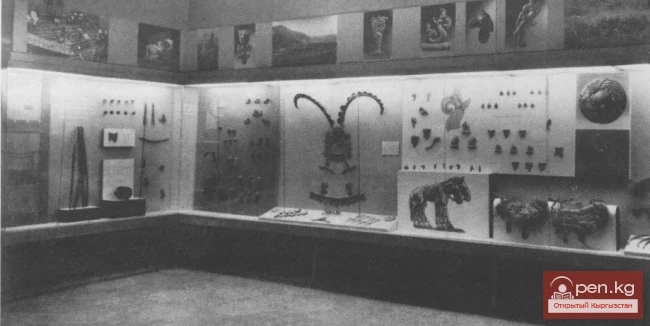

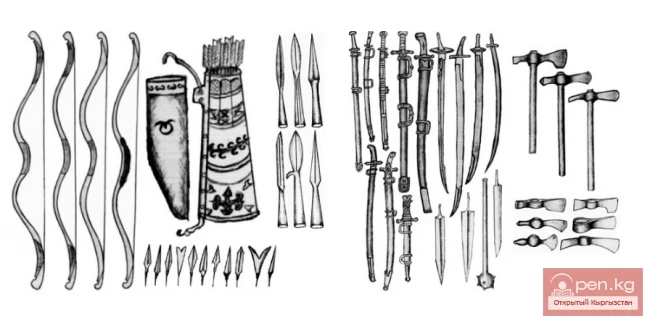

Monuments of Central Asian architecture, as one of the leading German art historians Burkhard Brentjes rightly noted, are invaluable material for the history of art. And not because there were no other forms of art in Central Asia in the past, but because mosques, mausoleums, palaces, and madrasas were silent witnesses, bearing the imprint of the Mongol invasions and the horrors of the ruling classes' terror against peasant uprisings. Some of them have survived to this day only as ruins, many are buried under the sands of deserts. Magnificent textile products have been destroyed, wood carvings burned, and numerous gold and silver items melted down or plundered. A small number have survived in tombs.

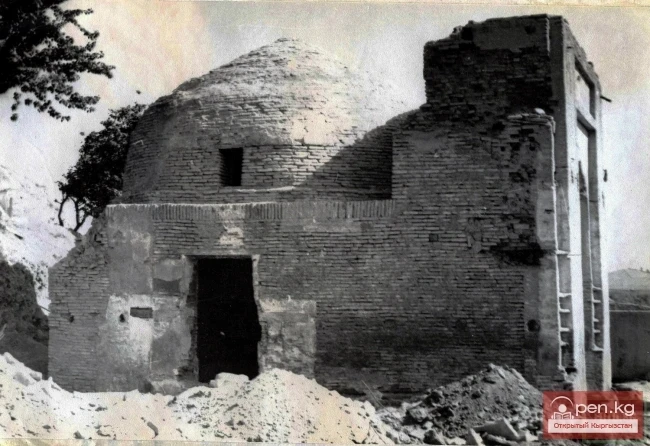

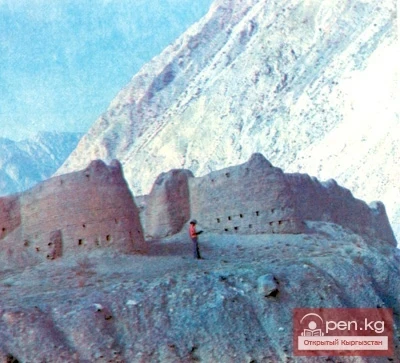

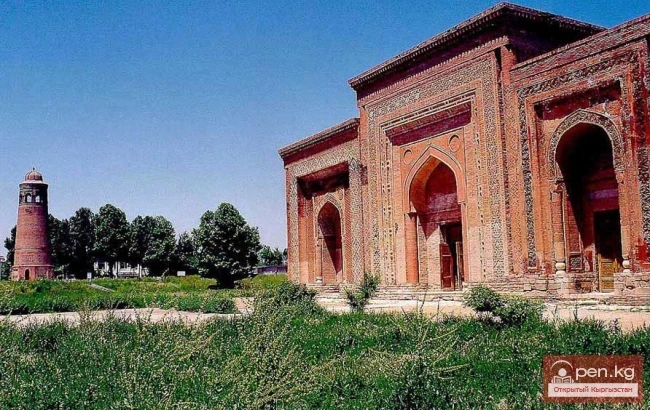

The only relatively well-preserved architectural monuments in Kyrgyzstan are the medieval minarets of Uzgen and Balasagun, the mausoleums of the Uzgen complex, and numerous Kyrgyz domes from the 18th to 19th centuries.

Classification. As early as the late 1940s, the famous Soviet archaeologist and pioneer of archaeological research in Kyrgyzstan A. N. Bernshtein rightly noted: “The mazars of the 18th to 19th centuries, often called domes (literally — domes), have been unjustly forgotten by researchers in Kyrgyzstan.” Unfortunately, this remark is still relevant today.

A. N. Bernshtein classified mazars based on their structural features into the following types:

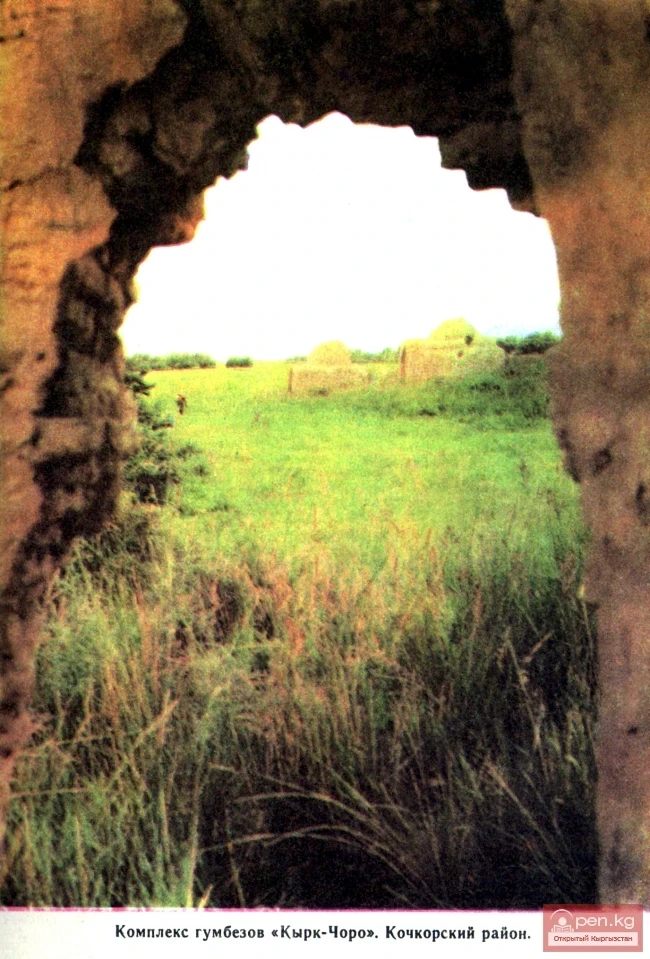

1 — centric type — domes with a spherical or parabolic dome (Kyrk-Choroo in the Kochkor Valley);

2 — portal type with spherical or conical domes (widespread everywhere, characteristic of the surroundings of Naryn and At-Bashy);

3 — portal type with three-quarter columns on the sides, mainly with spherical domes (Talas Valley).

Kumbez Bekmurata. At-Bashy

Burial structures in the form of a quadrangular enclosure with towers at the corners, sometimes imitating the lanterns of minarets, are encountered. Inside such a mausoleum usually stands a brick sagana — a gravestone (mainly at Issyk-Kul). Mazars differ slightly from this, where an elongated room adjoining the portal is covered with a semi-circular vault (Otuq, On-Archa).

This classification was taken as a working basis during the survey of domes in Central Tien Shan. And, it must be said, it has fully justified itself and received new scientific confirmation.

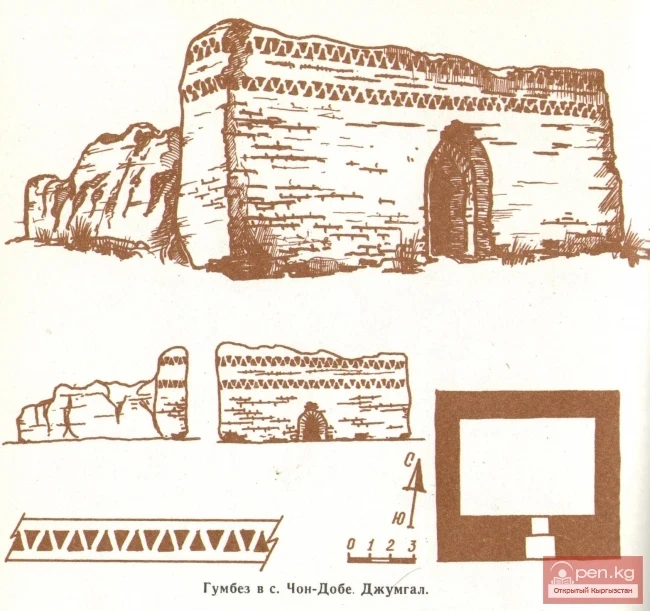

A distinctive feature of the mausoleums of Central Tien Shan is either the absence of external decor or its extreme insignificance. Domes contain the following elements: false windows and doors in the walls; rectangular recesses at the portal; friezes in the form of turned corner bricks, single and paired, laid on edge; “lattice” openwork masonry of diamond patterns; portal decoration with three-quarter columns, towers at the corners, with lanterns and conical finishes.

The portal was usually plastered with adobe, and the facade was completed with four through openings or niches, blocked by patterned stucco latticework, with tulip-shaped teeth running along the tops of the walls. Corner towers made of hollow adobe blocks are typical. They imitate a wooden column with a lantern instead of a capital.

Additionally, we note two more features:

• The applied Kyrgyz ornament on the outer side of the dome.

• The painting of the walls inside the dome and on the pediments (it was referred to by A. N. Bernshtein as an “exception,” although it was quite widespread).

Ornament and painting of Kyrgyz domes

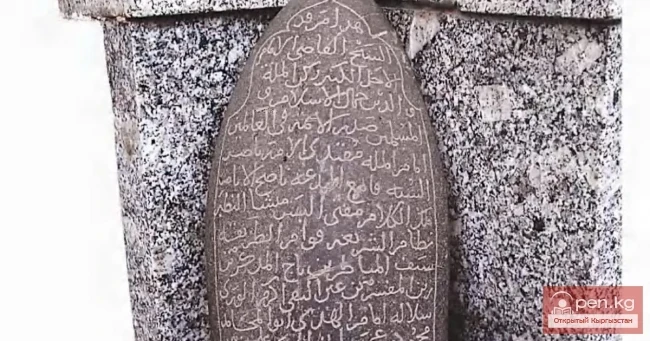

Among the architectural structures not noted by A. N. Bernshtein, we can point to “paired” domes (Taylaka and Atantaya) and “family” (when two or more saganas are under one dome). In addition, A. N. Bernshtein encountered inscriptions on domes and inside them, as well as sometimes on the portal, especially on the front side at the entrance arch. We have not managed to find a single such inscription. However, we have encountered isolated gravestones and processed memorial slabs with epitaphs.

To date, cult structures are the most widespread architectural monuments of the pre-revolutionary past in Kyrgyzstan. Most of them, and in the north, exclusively all, are associated with burial structures.

In his diary during a trip around Issyk-Kul in 1856, the famous Kazakh scholar Ch. Ch. Valikhanov noted that “the Kyrgyz of the last century were obliged to mark the resting place (resting place — B. D.) of some batyr with either a large earthen mound, or a wall in the form of a fortress, or a stepped tower. All this they did, depending on their means, from burnt or earthen bricks. The grandeur — the emblem of the power of the deceased.”

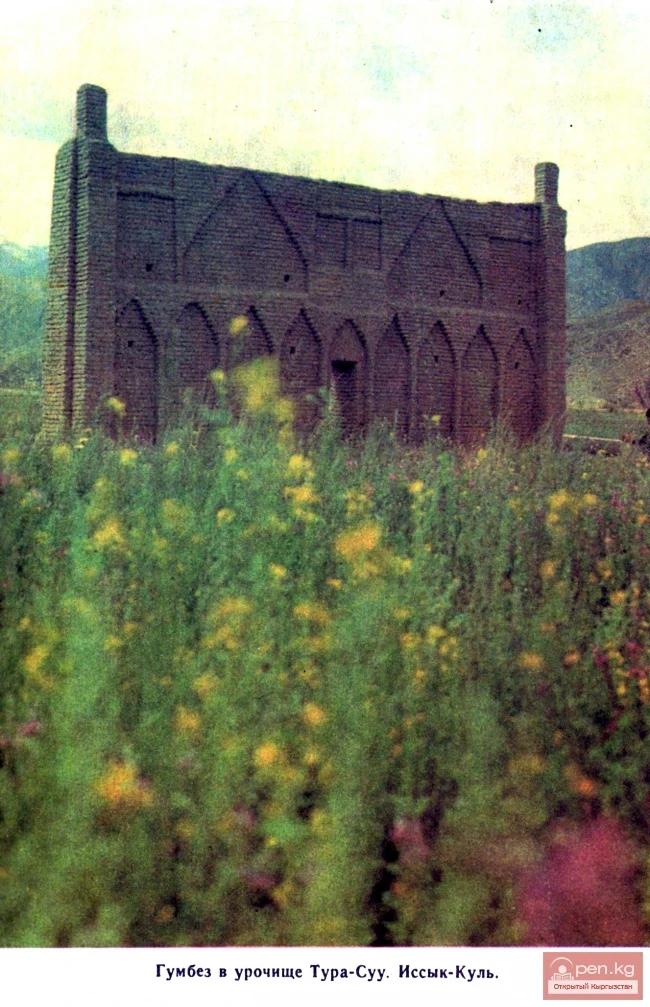

The traveler visited the dome of the prematurely deceased son of the powerful Sarybagysh manap Jantay at the mouth of the river Tyup and made sketches of it. The dome became widely known and became a standard for Kyrgyz mausoleums. For the construction of this dome, Jantay paid the master four “nines of livestock” and a hundred rams. The nines consisted of: the first — one slave and eight horses, the second — one camel and eight horses, the third — one racehorse and eight horses, the fourth — one ox and eight cows. The dome had the shape of a pointed dome structure with a powerful portal, decorated on top with lattice brickwork and two minaret lanterns, with airy lattice windows in the walls. The dome, according to Ch. Ch. Valikhanov, was whitened “very neatly,” and inside it had paintings in various colors “in the eastern style.”

Dome of Jarkinbai

A year later, P. P. Semenov-Tyan-Shansky, who visited the dome, noted that the mausoleum had a dome and two towers, with beautiful patterned embrasures for windows and doors with interesting decorations on the front wall. The interior of the mausoleum was high and cylindrical. In the center was a “sarcophagus.” The bricks were poorly fired, and the dome had already begun to deteriorate. Nowadays, naturally, no traces of it remain on the ground, nor has it survived in the memory of the people.

Domes had their own characteristics not only depending on the social status of the buried but also by territorial criteria. The mausoleums of the Pre-Issyk-Kul and Central Tien Shan regions primarily take the form of small stepped pyramids and rectangular enclosures up to 1 meter high. One of such archaic forms we encountered in Central Tien Shan was a stone mound from the 18th or early 19th century, topped with an ancient Turkic stone figure. Although not typical in its essence, this fact indicates the persistence of pre-Islamic traditions in Kyrgyz burial rites, which survived until the 19th century, and, as noted above, a certain continuity of the burial rite — from stone figures to domes.

In the traditional rite over the burial of an ordinary nomad, a pyramidal stepped gravestone with a rectangular base up to two meters high — sagana — was erected.

Judging by the simplicity of form, ease, and cheapness of construction, both types of burial structures were characteristic of the poorest layers of the population — ordinary nomadic herders.

A separate group can be attributed to domes built in the form of an enclosure without a dome, sometimes with a powerful portal decorated with decorative niches, intricate brickwork, and sometimes flanked by columns with minaret lanterns. The rectangular enclosures reflect a direct continuity from ancient pre-Islamic architectural forms. The appearance of the portal, moreover decorated with columns and minaret lanterns, is already an undeniable influence of Islamic culture.

In terms of architectural solutions and decor, mausoleums are quite diverse. The complex type monuments include the domes of the Taylak complex on the right bank of the river Kurtka at its confluence with the river Naryn, as well as the domes near the villages Ak-Moyun and Terek-Suu, in At-Bashy, the dome of Tura-Suu at Issyk-Kul, and many others. Such mausoleums are characteristic of Northern Kyrgyzstan, Central Tien Shan, and are less frequently found in the south.

Domes of Terek-Suu. At-Bashy

The next type of burial structure can be attributed to dome-shaped mausoleums of unpretentious form: from a simple adobe “yurt” with a top to a low spherical dome, built directly from the ground using tromps, or resting on a rectangular base in the form of an enclosure. The domes are laid with ring masonry, and the arched door opening is inscribed in a small portal or slightly raised facade wall. The foundation is usually absent. These are the so-called domes. Their decoration used elements in the form of geometric patterns (diamonds, crosses, triangles, rectangular grids — shapes easily laid with adobe bricks), tracing back to the origins of traditional Kyrgyz ornamentation.

In 1945-1949, while surveying a series of Kyrgyz domes in Central Tien Shan and noting two of their varieties with a predominance of rectangular enclosures and dome-shaped structures with varying degrees of portal development, A. N. Bernshtein concluded: “Kyrgyz mausoleums-domes are interesting in that they most vividly express the builder's tendency to restore, reproduce in construction the idea of the round plan of the yurt and its spherical covering. The height of the dome and its ratio to the body of the building repeat the basic proportions of the heights of the yurt's frame and its covering.”

Speaking of Central Asian architecture, Burkhard Brentjes notes that although the basic principles of constructing mosques, madrasas, and mausoleums were supposed to serve the ideas of Islam, they were so deeply rooted in the architecture of the pre-Islamic period that even Islamic architecture was defined by the forms and construction possibilities that had developed over thousands of years.

This remark is even more relevant to late Kyrgyz domes, the paintings of which are not only far from Islam but sometimes directly contradict it. We mean the narrative paintings of the domes with scenes of animals and even people, which were strictly prohibited by the canons of Islam.

When constructing mausoleums, the interior of the dome and walls were sometimes plastered with a lesso solution, on which ornamentation was occasionally applied. The upper part of the walls of the mausoleum and the enclosure was sometimes laid out with geometric ornamentation. Bright representations of them are provided by drawings and photographs of mausoleums. One of the first drawings of a Kyrgyz dome on the river Tyup in Pre-Issyk-Kul, as we noted, was made in 1856 by the Kazakh scholar Ch. Ch. Valikhanov, who noted that “if the Kyrgyz have their own artistry, architecture, then undoubtedly, it is monumental architecture, the architecture of graves.”

According to P. P. Semenov, supported by other researchers, the Issyk-Kul Kyrgyz sometimes used glazed bricks from earlier medieval ruins, including underwater ones, in the construction of domes.

In the paintings of Kyrgyz domes (Nogai, Baitika, also Talas ones), the color blue is present. Even Ch. Valikhanov noted in his diary during his trip around Issyk-Kul that for the Kyrgyz, the color blue signifies mourning.

With reference to G. A. Kolpakovsky, academician V. V. Bartold mentions two Kyrgyz domes on Issyk-Kul, built from medieval bricks. These are the domes of Balbai, for which bricks were taken near Koysu, and the dome of Tily-Akhmet, built from Koysar brick. The same dome was encountered by the scholar himself on the way from Przhevalsk to the village of Slivkino (modern Pokrovka).

Chon-Alaï domes

Mausoleum-palaces. The next group of monuments includes mausoleums, in which a powerful portal with columns stands out prominently. These are mainly large domes made of adobe or burnt bricks with established Islamic architectural traditions. They were usually erected in honor of well-known Muslim figures of the region. Such mausoleums were most widespread in southern Kyrgyzstan, adjacent to the Muslim cult centers of Fergana.

A characteristic example of this group of monuments is the mazar of Khoja Biala in the Osh region, built in the late 17th to early 18th century over the grave of a famous local mystic. The mausoleum is rectangular in shape (4.55 X 4.68 m), with a portal flanked by columns covered with colored adobe with geometric patterns. The top of the portal is adorned with geometric ornamentation on the adobe. The spherical dome is crowned with a ceramic detail in the shape of a jug.

10 km to the south, in the center of the village Uch-Kurgan, another similar mausoleum — mazar of Ishan Balkhi — was erected in the late 19th century. In plan, it is a rectangle measuring 7.72 X 5.70 m. The 6 m high portal also included columns. It was decorated with ornamentation executed on colored adobe. Both mausoleums are made of pakhsa and adobe on a lesso solution.

The architectural composition of the examined types of burial cult structures is a peculiar refracting of residential architecture in the perception of the people, original works of folk architecture, in which local national traditions are clearly visible. Historians and architects conclude that burial structures in Kyrgyz cemeteries have completely unusual forms and are based on the free creativity of folk masters, unrestrained by the canons and professional traditions that existed in “Muslim” architecture.

Dome of Susamyra

Currently, the overwhelming majority of burial structures from the 17th to 19th centuries are either completely destroyed or in a state of neglect. The reason for this lies both in the impermanence of the building materials used, the low level of construction techniques, and in the prejudice of Kyrgyz people against repairing memorial cult structures (reconstruction and repairs were carried out extremely rarely and mainly in southern Kyrgyzstan).

The surveyed domes have answered many questions, in particular, about architecture, forms, purpose, and classification. At the same time, a whole series of new questions have arisen, which can only be resolved in a complex manner, summarizing all materials on Kyrgyz domes throughout Kyrgyzstan and comparing them with other Central Asian mausoleums. Much is still unclear. It is necessary to identify the origins and roots of dome-portal Kyrgyz architecture and ornamentation, establish a firm dating of the domes, specific national features in architecture and decor, and their specific connection with historical events reflected in legends and folklore.

For the first time, A. N. Bernshtein drew attention to Kyrgyz domes during expeditionary work in Kyrgyzstan in 1938-1940, “which,” he said, “in their architecture bear traces of memories of the constructions of Central Asian medieval architecture.”

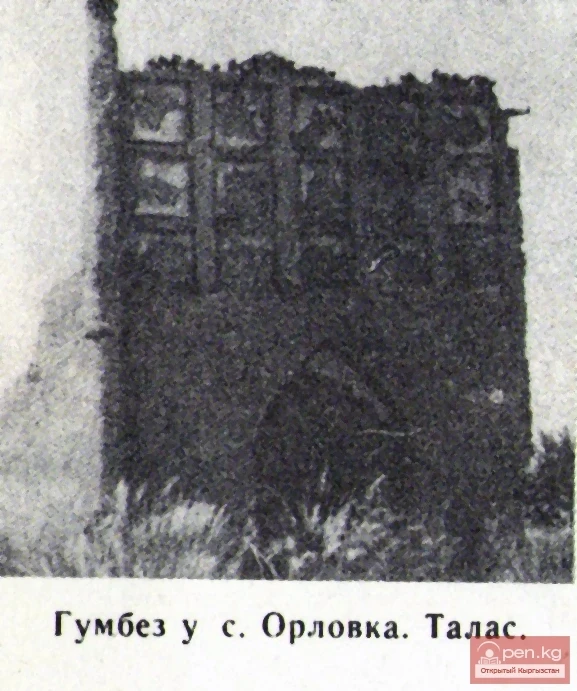

In the Talas Valley near the village of Orlovka, as well as in the area of Besh-Tash, there still stand, albeit increasingly deteriorating each year, domes with once original artistic paintings. Here are traces of floral ornamentation across the entire dome, symmetrically repeating geometric motifs, and depictions of horses, camels, dogs, wild goats, and leopards, even human figures. It is precisely about the Talas domes that A. N. Bernshtein wrote enthusiastically: “The amazing expressiveness of the fresco painting inside them resembles old samples, and the depiction of living beings, so forbidden by Islam, beautifully shows the artist's origin from a nomadic environment, which was by no means a zealous guardian of Islamic ideas. The hand of such an artist may also belong to the graffiti-style depictions of people, horses, mountain goats, sometimes engraved on rocks, sometimes inside domes.”

Dome near the village of Orlovka

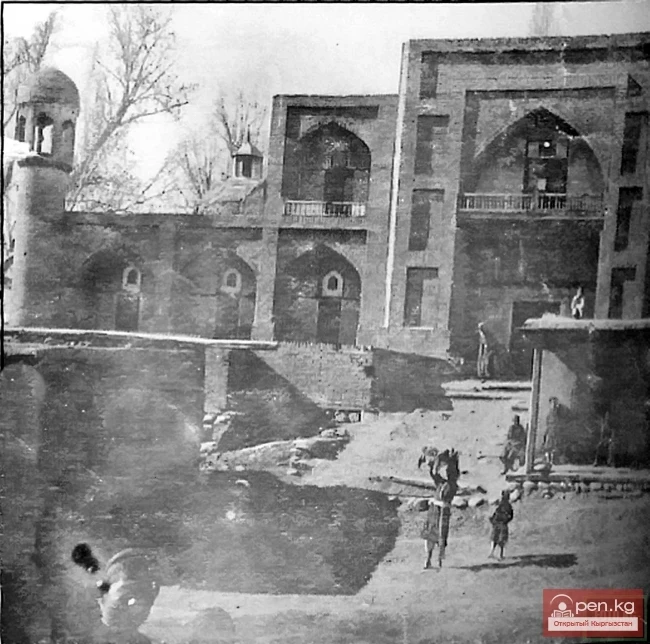

Mosques existed in a number of Kyrgyz settlements in the Fergana Valley (the villages of Kara-Bagysh, Bulak-Bashi, and others). Until the mid-20th century, interesting mosques and madrasas from the 18th to 19th centuries were preserved. These included two now-missing Osh mosques, the so-called mosque of Sydykbai (19th century) and the mosque of Muhammad Yusuf-bai-khodja (1909-1910), as well as the mosque of Ravat Abdullah-khan, located at the foot of the mountain Takht-i Suleiman in the city of Osh (17th-18th centuries). After numerous reconstructions, the architecture of the latter building has been fundamentally altered. It now houses a local history museum.

Large madrasas existed in Uzgen (madrasah of Arab-bai Nauruz Baiulu), in Karasu (madrasah of Alymkuла), and in other large villages of Southern Kyrgyzstan.

In the construction of madrasas and mosques, even more than in burial structures, rich architectural decor was used, executed in the spirit of deep folk traditions. This is evident in wood and adobe carvings, ornamental masonry, and the delicate and bright coloring of the ornamentation. In the planning and architectural ensemble, the traditions of Islam continued to dominate, but local motifs were increasingly resonating within them.

“Each of the elements — dome, portal, carved terracotta, which together created this architecture — has a more complex origin, rooted in the culture of nomads who interacted with the sedentary tribes of Central Asia,” wrote A. N. Bernshtein in conclusion to his book on the architectural monuments of Kyrgyzstan. “The synthesis of these phenomena, which gave a new page in the history of Eastern architecture, belongs to the peoples of ancient Kyrgyzstan, who have preserved to this day a remarkable narrative about ancient architecture in the monuments located at the foot of the Tien Shan and Alai...” Not exaggerating the role of ancient Kyrgyz architecture in the architecture of the East, we nevertheless believe that the totality of such cult monuments, like domes, mosques, and madrasas, represents an important object for their historical and architectural study, which is still just beginning. Their survey for the “Register of Historical and Cultural Monuments,” reconstruction projects for preservation and museum exhibitions will serve not only scientific but also practical purposes as monuments of folk craftsmanship of historical and cultural significance.