Cult Monuments of Osh

It is particularly difficult to characterize the culture of the population of Osh during the Kokand period, not only due to the scarcity of sources.

The Kokand Khanate was at such a stage of development that there are no grounds to speak of cultural progress: the culture of the preceding Timurid period was much higher. Moreover, very few sources on the history of culture from the Kokand period have survived. We can only affirmatively speak about those architectural and manuscript monuments that have survived to this day or are mentioned in later sources. We even find it difficult to characterize the material culture of the townspeople, as this is a completely unexplored area, and studying it is a task for the future.

Therefore, we will focus only on the monuments of cult architecture from the 18th to 19th centuries and the manuscript books from this time, to which we have been involved in identifying and collecting in recent years during a historical and archeographic expedition.

The cult monuments include mausoleums—gumbazes, mazars, mosques, and madrasas, which are of architectural interest.

The burial structures of the Kyrgyz—gumbazes were usually built in the traditional Islamic style from unburnt, and less often, burnt brick. They were erected in honor of mythical or historically lived Muslim "saints" and over the graves of prominent local feudal lords. These included the gumbazes at the foot of Suleiman Mountain (where, by the way, the ancestral cemetery of Kurbandzhan was later established, as well as the gumbaz of the "Alai Queen" herself), directly in the city of Osh, as well as the mazar from the late 17th to early 18th century of Khoja Biala, the mazars of Ishan Balkhi in Uch-Kurgan and Arslanbob in the eponymous kishlak of the Osh region. In Osh, a correspondent of the Muslim newspaper "Vakt" ("Time") wrote in 1913, there were several mausoleums and many mosques, especially many under Suleiman Mountain and around the cemetery. Prayers were held here. Moreover, on one side of the mosque, a yak's tail could be displayed on a long pole, and on the other—a flag.

The modest external architectural design of the gumbazes and mazars of Osh significantly lagged behind the well-known similar monuments of Central Asia from earlier times, in particular, the Samarkand monuments of the Timurid era, the Uzgen monuments of the Karakhanid period, or even the contemporary Bukhara ones. Their lifespan was also short, and many of them have not survived to our time, as have the madrasas and most mosque buildings.

According to archival materials, it can be concluded that in the last years of the Kokand Khanate, there were 6 madrasas and 147 mosques directly in Osh and its immediate vicinity.

The Alymbek madrasa was highly regarded by contemporaries as the only worthy architectural structure in Osh in the mid-19th century. It was compared to the khan's madrasas in Kokand and similar ones in Bukhara. There were also other, more modest madrasas—Alymkula, Khalmurza-bay.

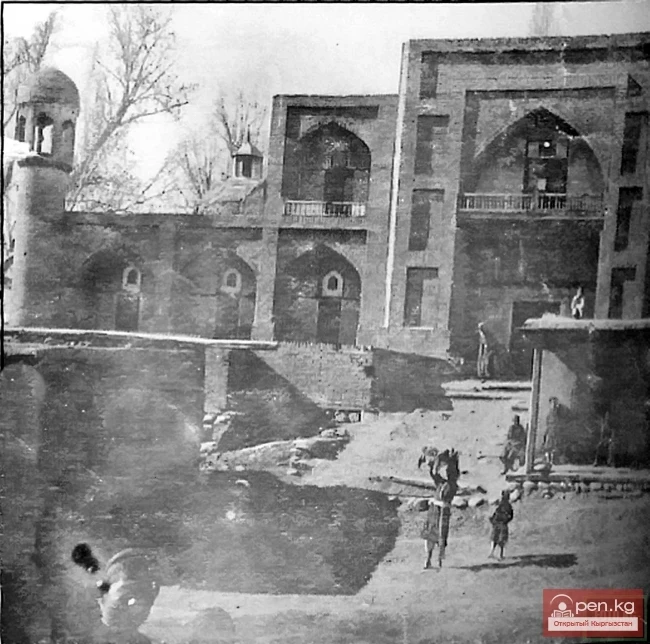

The madrasa and waqf of Alymbek have been described in detail above. In general, this complex structure represented not only historical but also architectural interest as a monument of the former architecture of the city of Osh, southern Kyrgyzstan, and indeed the Ferghana Valley as a whole. The madrasa occupied an area of more than a quarter of a hectare and represented a significant architectural complex. It was a typical structure from the late stage of cult architecture in Central Asia, an example of the Ferghana architectural and construction school.

Externally, the madrasa presented a closed symmetrical composition, with a vast courtyard surrounded by brick walls, which separated the internal life of the madrasa from the outside world; they were more than five meters high, and at the corners stood four minarets over 15.0 m tall, which gave the structure a distinctive appearance. The entrances to this complex were emphasized by high monumental portals with deep pointed niches.

The characteristic picturesque view of the overall silhouette of the madrasa was given by five domes, minarets at the corners, and two portals. This complex was quite imposing among the surrounding lowly shabby residential buildings. The courtyard of the madrasa had a rectangular shape, surrounded by pointed arches. In the courtyard, there was a hauz with running water, brought by an irrigation channel from the Ak-Bura River. One could ascend to the flat roof and the second floor via spiral staircases in the minarets. What the decoration of the rooms was like is difficult to judge now, but it should be assumed that the decor of the rooms was given certain attention.

The madrasa, as already mentioned, was built of burnt brick on a ganch mortar. During its existence, it underwent numerous repairs, extensions, and reconstructions, which were even specifically stipulated in the waqf documents.