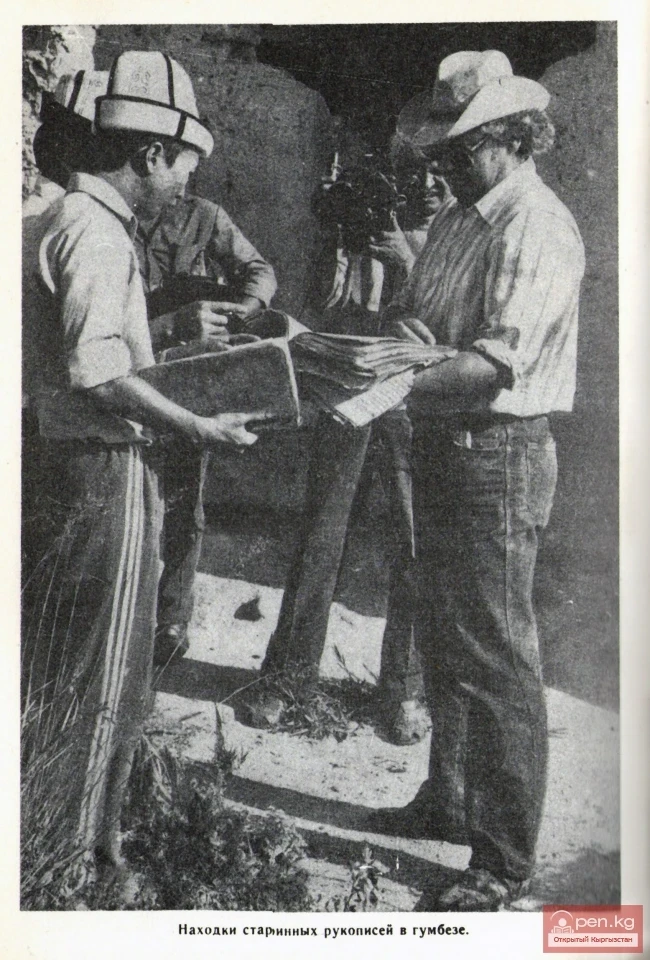

The material culture of the Kyrgyz people from the 16th to the first half of the 19th century has not yet been the subject of special study, and during our expeditionary work, it was important for us to gather any information in this area. Moreover, the study of fortresses was interconnected with the nature of Kyrgyz settlements and dwellings, while the ornamentation and paintings of epitaphs and domes directly relate to the traditional decorative applied art of the Kyrgyz.

We also studied the material found in published pre-revolutionary literature, utilizing works on material culture and decorative applied art that chronologically cover the late 19th to early 20th centuries, by Kyrgyz ethnographers such as K. I. Antipin, S. M. Abramzon, T. D. Bayaliyev, E. S. Sulaymanov, L. T. Shinlo, and others.

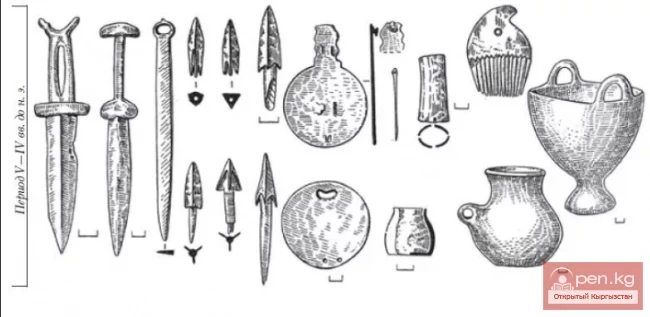

Scholars find the genetic roots of the material culture of nomads in the culture of ancient and medieval nomadic tribes of Central and Central Asia—from the Sakas and Usuns to the Turks and Mongols. The ancient origins of many of its elements are convincingly documented by written sources and numerous analogies discovered during archaeological excavations. These can be traced in the type of dwelling, clothing, embroidery and weaving arts, motifs of ornamentation, decoration of horse harness and weapons, jewelry, and much more.

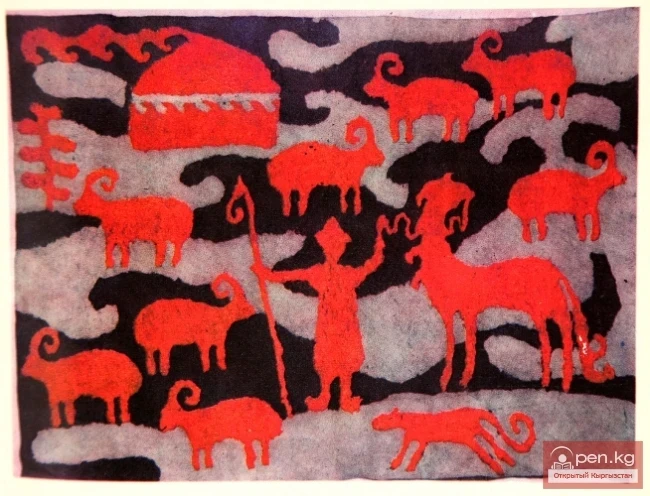

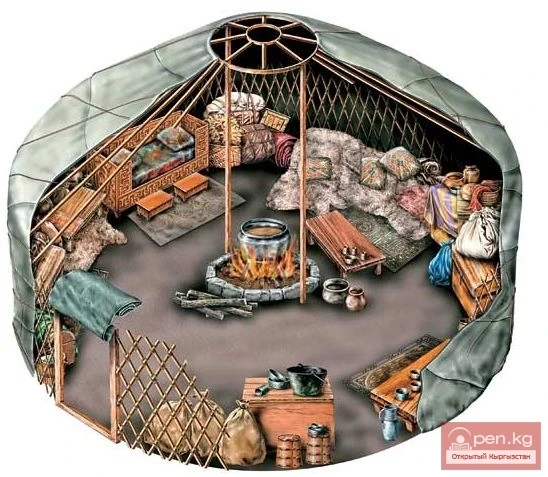

The material culture of the Kyrgyz was deeply influenced by nomadic pastoralism and patriarchal-tribal life. Everything—from the type of dwelling and utensils to clothing and means of transportation—was subordinated to the requirements of frequent migrations over long distances. In its main features, the culture was unified across the entire territory inhabited by the Kyrgyz, although it also had its local peculiarities. Unfortunately, objects of material culture from the Kyrgyz of the 16th to 18th centuries have not survived. Therefore, considering the deep traditional nature of the culture of the Kyrgyz people, it can be characterized based on the sources available to us from the late 18th to early 20th centuries.

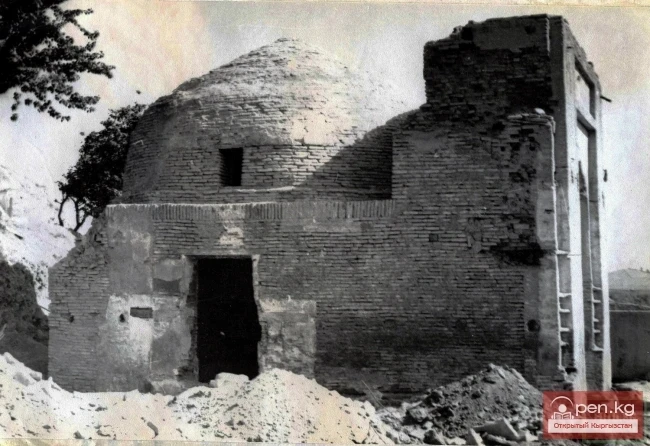

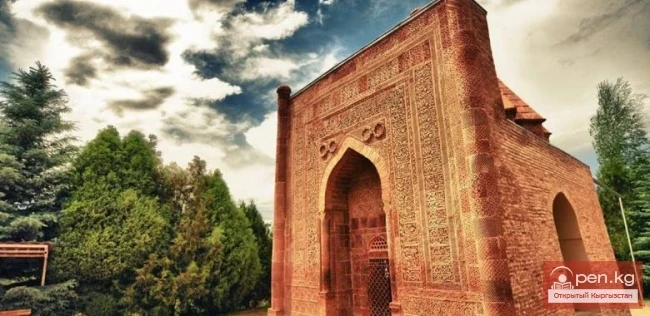

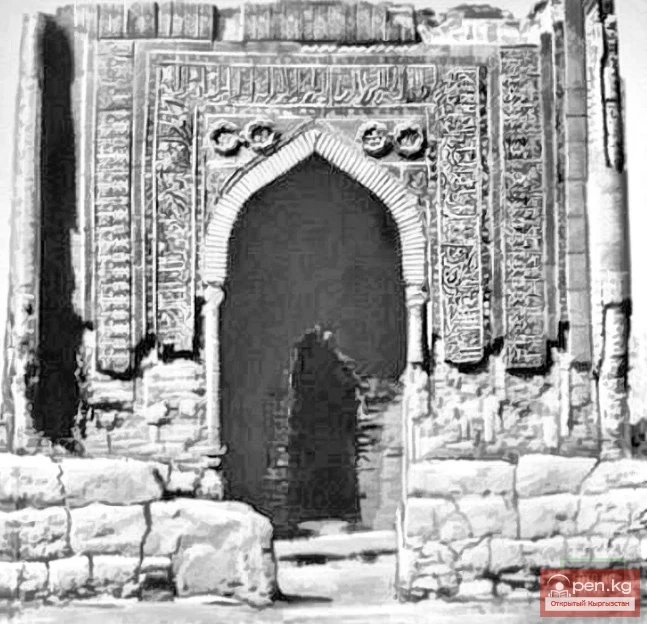

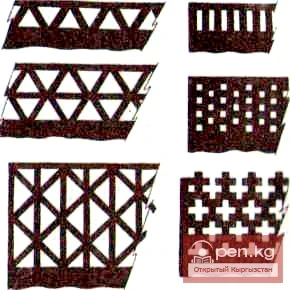

Samples of decorative brickwork of the domes

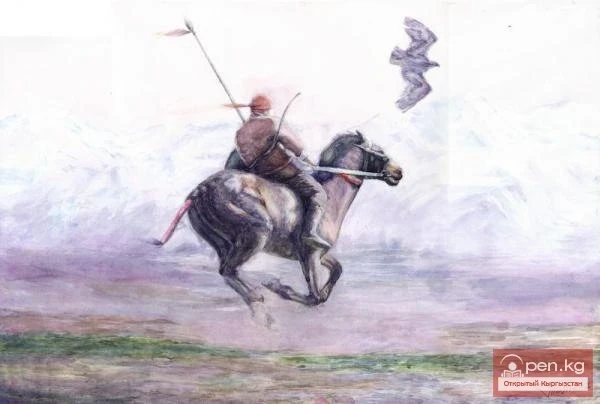

A valuable visual source for characterizing the traditional life and clothing of the Kyrgyz are the sketches and completed paintings of the famous Russian artist V. V. Vereshchagin. In 1869-1870, he undertook several journeys through Central Asia, including Kyrgyzstan, leaving behind landscape and thematic sketches of Issyk-Kul and Barskoon, the migrations of the Kyrgyz, as well as completed paintings such as "The Rich Kyrgyz Hunter with a Falcon" and "Kyrgyz Yurts on the Chu River." The author expressed his sincere admiration for the people and the everyday life of Central Asia. The last painting by the artist was called "ethnographic" by the famous Russian critic of the last century V. V. Stasov. It depicts Kyrgyz migrations, ails, and the interior decoration of a yurt adorned with brightly colored carpets.

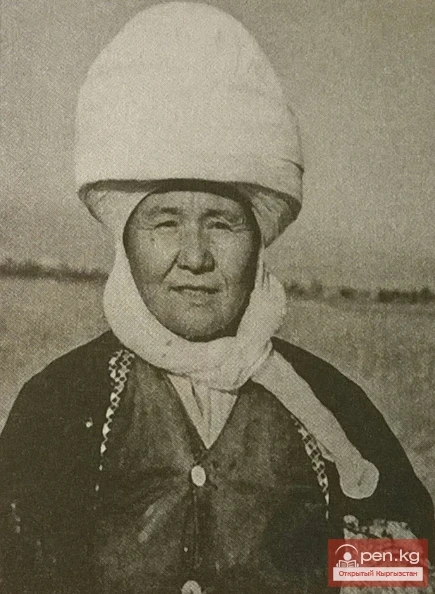

One of the paintings depicts a Kyrgyz ail. The rich color palette conveys the life of the nomads. Women in white clothing and white headwear—elechek—are engaged in everyday work. Three horsemen ride by. In the foreground is a felt Kyrgyz yurt adorned with colorful carpets woven with traditional geometric patterns. At the foot of the mountains, by the bank of a small river, the ail is situated.

In two other paintings, the process of the Kyrgyz migrating from the mountains to the valley is shown. Camels loaded with simple nomadic belongings carry disassembled yurts. Women on camels, covered with felt blankets, a hunter in a striped robe with a falcon on his left arm, an old man with a child on an ox. This is how the ancestors of the Kyrgyz lived and migrated for millennia, and this is how the artist captured the process in 1869-1870, drawing a series of sketches from life, from which later completed paintings were made.

During migrations, all property was loaded onto camels, while horses were used for riding. The poor, lacking camels and horses, used oxen for this purpose. Migration was a significant and joyful event for the Kyrgyz: women dressed in their best clothes and sang songs.

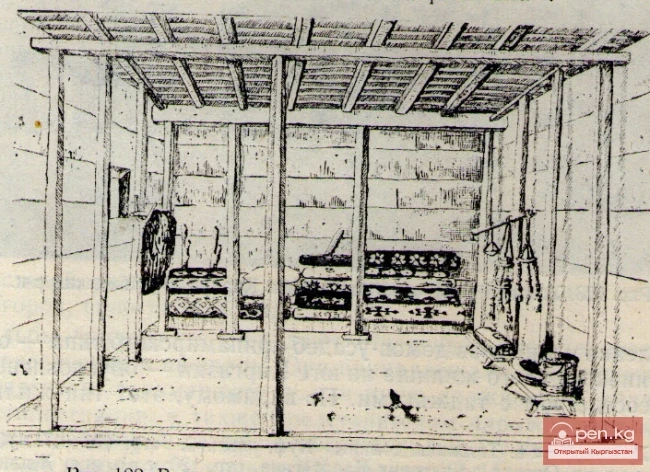

Overall, the Kyrgyz yurt corresponded to the spirit of nomadic times, meeting the needs of a mobile lifestyle. Its traditional elements are uniquely captured for centuries in the clay mausoleums erected over the graves of the deceased. However, Kyrgyz mausoleums—domes—cannot be called models of yurts in clay. They also had elements that were not characteristic of typical nomadic dwellings, but were typical of clay, wooden, or frame structures with windows, doors, portals, and patterned lattice walls. The Kyrgyz already had dwellings of this type. Neighboring sedentary Uzbek-Tajik settlements, they transitioned to sedentary life and built their own houses. Here is how one such Kyrgyz house is described by the Russian traveler A. P. Fedchenko:

“...Turning south, we saw the summer camp of Kara-Kazuk: on a site overgrown with huge junipers, several yurts were spread out... The yurts were occupied by Kyrgyz families, and while we cleared one of them, we took shelter from the rain and cold wind in a wooden house. I deliberately emphasize the word ‘wooden’: this was the only indigenous wooden structure made of a single tree that I had seen. It was built so that the hewn juniper logs were placed vertically, secured in the grooves of logs tied together at the top. The boards were not fastened, there was no chinking, and therefore fingers could easily pass through the cracks. Overall, it had the appearance of a cubic cell, with an area of about two square fathoms. The entrance was arranged on the southern side and could be locked: the boards were removed from the grooves of the weave and then inserted again, as is usually done in shops at indigenous bazaars. The purpose of this extension, made recently by the Kyrgyz bey migrating to Kara-Kazuk, was partly religious: it served as a mosque, but at the same time, it was a place for travelers to stop, i.e., it would be a place to stop, because it was made recently, just before the cessation of relations with Karategin. Here we saw, therefore, a combination of a prayer building with an inn.”

The domes also served as places of worship: people would come to pay their respects, prayers were held here, but in bad weather, travelers or shepherds with their livestock caught off guard would also find shelter here.

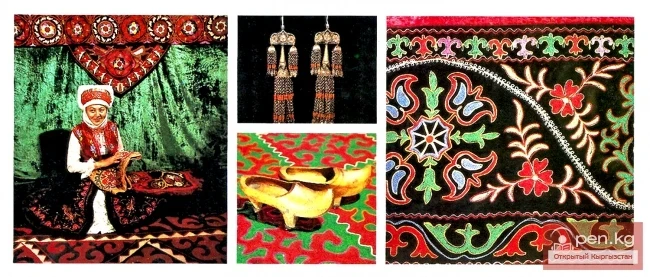

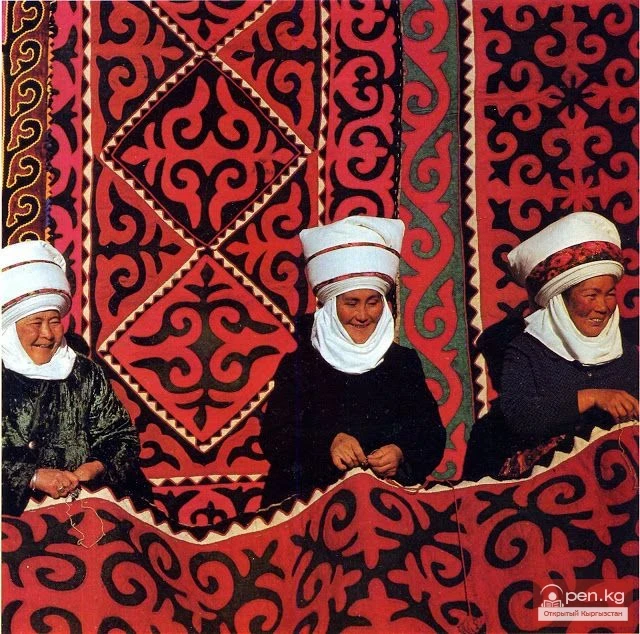

The desire to satisfy aesthetic needs, to maximize the use of all artistic possibilities for decorating the dwelling, gave rise to various types of decorative applied art among the Kyrgyz, the roots of which go back to ancient times. Applied art was the creation of talented masters who emerged from the working people. Its aesthetic and emotional impact can only be compared to national folklore and music.

The decorative applied art of the Kyrgyz was inextricably linked to other types of domestic production. Practically every item made by Kyrgyz craftsmen or craftswomen was lovingly decorated with rich and original ornamentation. Domestic production constituted a “necessary attribute of a natural economy,” based on the use of raw materials from pastoral farming, hunting, plant materials, and metal. By the mid-19th century, Kyrgyz domestic production was not an independent industry; tools were primitive, labor remained exclusively manual, and as a result, it was low in productivity. Kyrgyz craftsmen mastered the art of processing and decorating felt, wool, leather, weaving, leather embossing, embroidery, blacksmithing, jewelry making, carpentry, and even construction techniques. A unified artistic style was developed across the entire territory inhabited by the Kyrgyz, which is particularly evident in Kyrgyz domes with their traditional elements. A decisive role in this was played by centuries-old continuity in culture.

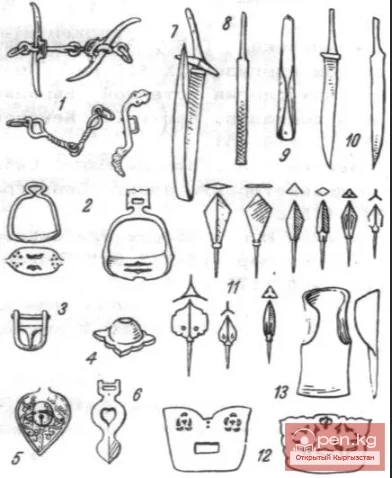

The material basis of Kyrgyz decorative applied art in the past consisted of industries related to the processing of livestock products, plant raw materials, and metalworking. All of them were at the stage of domestic production, not separated from pastoralism. The main types of Kyrgyz applied art in the past included: the production of patterned carpets and household items from ornamented felt; the making of woolen pile carpets; the weaving of artistic mats from chiy and woolen threads; embroidery on felt, leather, and fabrics; leather embossing; wood carving; artistic metal processing, construction, architectural decoration, and painting of mausoleums-dome.

The Kyrgyz people created a rich ornamentation, numbering over 3,500 known combinations. It features several groups or complexes that are in one way or another characteristic of the art of other peoples of Central and Central Asia, however, the greatest closeness and even kinship is observed in Kyrgyz and Kazakh ornamentation. The main defining complex of the decorative art of the Kyrgyz people includes motifs that include various variants of mueiz (horn-like elements), waves with curls, palmettes, cross-shaped figures, and some others. Researchers conditionally call this complex “Kipchak,” as it is found among a number of contemporary peoples, in the ethnogenesis of which the Kipchaks participated. It was finally formed in the environment of late nomads in the 9th-12th centuries, but its roots can be traced back to the 6th-5th centuries BC. The ancient items made of felt, leather, and wood discovered by Soviet archaeologists during excavations of the burial mounds of nomads from the Saka period in Altai allow us to conclude that certain traditions of this art undoubtedly underlie the artistic samples created by Kyrgyz masters. In the appliqués on the felt carpet from the fifth Pazyryk burial mound and on the leather decorations of horse harness from the first Tüektin burial mound, one can see patterns that researchers consider prototypes of Kyrgyz ornamental compositions. There are cross-shaped and rhombic figures with horn-like curls, rhombic nets, and many others.

These ornamental motifs have long been characteristic of the population of the Tian Shan. For example, horn-like curls and a rosette pattern are depicted on the plaques from the Saka period of the 6th-3rd centuries BC from Barskoon. In developed form, they can be traced in artistic metal products and in the ornamentation of ceramics of the ancient Turks from the 7th-12th centuries, and they are often found in Kyrgyz patterns as well. Signs of deep traditionality are also observed in other ornamental motifs. Some of them, according to researchers of Kyrgyz patterns, can be traced back to the Bronze Age.

Traditional Kyrgyz ornamentation is captured on ceramics, artistic metal, in carving on clay or in wall painting, dating back to deep antiquity up to the Middle Ages and found on the territory of modern Kyrgyzstan.

A significant interest lies in the question of the connection between the art of the Kyrgyz and the art of agricultural regions. These relationships date back to the early Middle Ages. Even during the dominance of the Western Turkic Kaganate (6th-8th centuries), the art of nomads experienced a noticeable influence from the artistic culture of agricultural Sogdiana. The Sogdians, in turn, borrowed much from the nomads. Thus, Sogdian ornamental motifs transferred to clay tables (dastarkhans) were widely spread in the houses of the Karluks in the 8th-10th centuries. The influence of Sogdian art on the Turkic-speaking population of Kyrgyzstan was also characteristic of the 11th-12th centuries.

All this explains the presence in the decorative applied art of the Kyrgyz of a number of ornamental motifs that are common with Sogdian-Turkic or closely related to them, such as palmettes, heart-shaped figures, lyre-like variations, and sprouts.

It is also worth noting the commonality of many ornamental motifs of Kyrgyz decorative applied art with the motifs of the decoration of architectural monuments of Kyrgyzstan, dating from the 11th-14th centuries, such as the Uzgen architectural complex, Balasagun mausoleums and minaret, Shakh-Fazil mausoleum, Manas dome, which can be considered direct predecessors and models for imitation for subsequent Kyrgyz domes of the 18th-19th centuries. The decoration of these structures reflects horn-like motifs, patterns in the form of paired spirals, trifoliate designs, wave-like sprouts with semi-palmettes branching off from them, stepped squares, “towns,” diagonally crossed squares, and other figures, which fully correspond to similar motifs of traditional Kyrgyz ornamentation. The plant ornamentation on the inner side of the domes of the Talas domes and the dome of Baytyk in the Chuy Valley, as well as the external relief ornamentation of the domes of the village of Lama in the Jumgal region, the architectural ornamental brickwork of the dome of Taylak in the Ak-Tal region, and many other domes of the Tian Shan convincingly testify to their traditionally Kyrgyz origin and deep centuries-old roots.