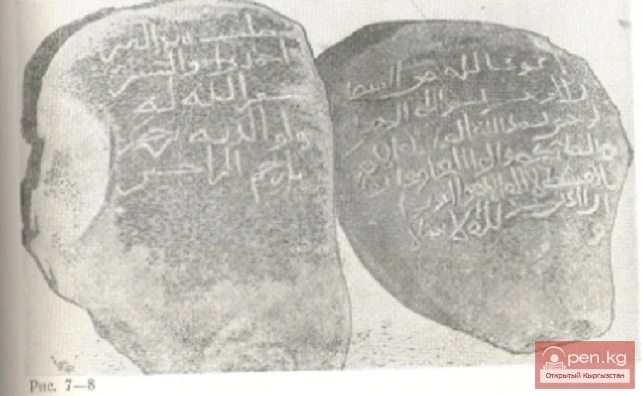

Findings of Nestorion Epitaphs

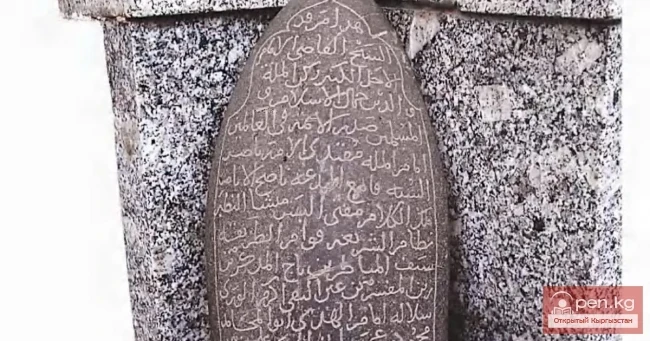

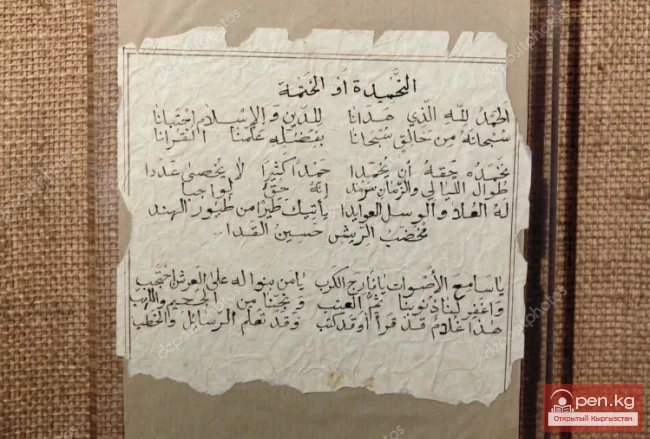

Syrian and Syro-Turkic Nestorion epitaphs form the most numerous group of epigraphic monuments in the territory of Kyrgyzstan. Currently, about 700 such monuments are known.

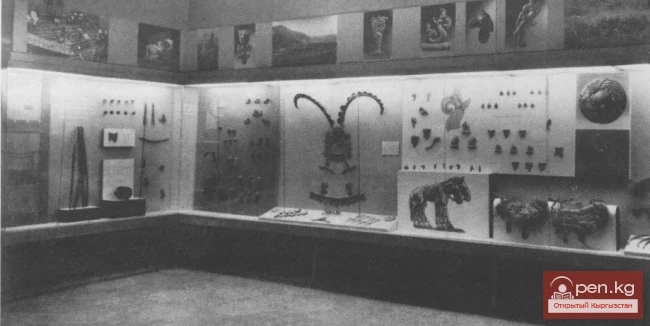

The overwhelming majority of them were found in the late 19th century. Unfortunately, only a small part of these epitaphs has survived to this day. They are kept in the State Hermitage, in museums in Almaty, Frunze, Tashkent, and some other cities. A significant portion of the epitaphs has been lost. It is important to note that almost all of them were discovered on the territory of Kyrgyzstan. Nestorion epitaphs are of great interest for syriology and turkology, as well as for the study of the history of Christianity.

“Syro-Turkic studies have already provided and will continue to provide much interesting and important material for the study of the centuries-old and multifaceted connections of Central Asia with the peoples of the Near East in the Middle Ages,” said R. A. Guseinov at the All-Russian conference of archaeographers and medievalists held in Moscow in 1972. At this same conference, the expediency of publishing a consolidated "Corpus of Syro-Turkic Inscriptions of the USSR" was emphasized. Work on this topic is being conducted at the Institute of Language and Literature of the Academy of Sciences of the Kyrgyz SSR.

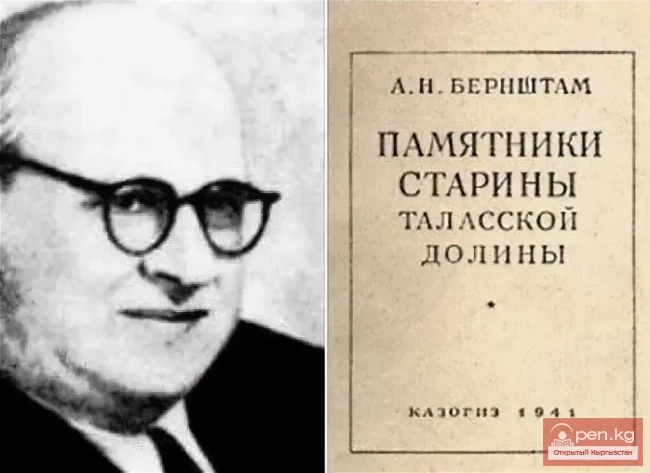

The Semirechye Nestorion epitaphs were actively researched and published even before the revolution. This work continued during the Soviet era. Stones with epitaphs continue to be found even today, both during archaeological excavations and agricultural work, in the latter case often showing significant damage.

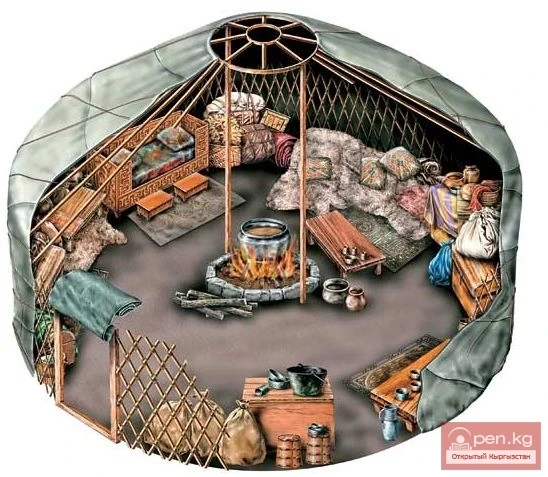

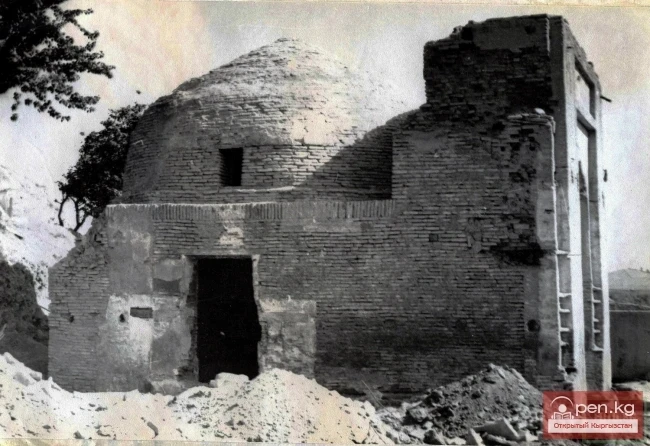

The findings of Nestorion epitaphs in the vicinity of the village of Kara-Dzhigach are not accidental. In the 13th—14th centuries, there was a city called Tarsakent here (literally "city of Christians," from Persian tarsa and Sogdian kent). The geographical work of Khimdallakh Kazvini "Nuzhat-al-qulub" (1340) indicates that part of the population of the Chuy Valley consisted of Christians—tarsas (referring to Nestorions). The appearance of Nestorions in the Chuy Valley dates back to much earlier times. For example, the discovery of a Christian church with a cemetery from the 8th century at the Ak-Beshim settlement, as well as Christian complexes at the Burani settlement and in some other places, may testify to this.

According to information provided in the late 19th century by N. N. Pantusov, a cemetery with Nestorion epitaphs was located 10 versts from the city of Pishpek (now Frunze) along the Zhelaiyr (Zhelargy) irrigation canal, flowing from the right side of the Alamedin River, 2—3 versts from the Kyrgyz ridge. The cemetery occupied an area 120 fathoms long and 60 wide. N. N. Pantusov, who studied it in detail, noted the presence of small mounds and a small earthen elevation in the shape of an isosceles triangle, but found no traces of a church or chapel. By the end of the 19th century, the cemetery was already being plowed by local residents. The stones with inscriptions lay in disarray, in piles or singly, some were thrown onto elevated places, many were plowed under and ended up beneath the soil.

When local Kyrgyz residents were questioned, it was found that they had heard nothing about these stones and knew no legends associated with them.

Researchers of the settlement near the village of Kara-Dzhigach in 1929, A. I. Terepozhkin and later P. N. Kozhemyako, noted that it was poorly preserved, lacked clearly defined topography, except for small hills and a high central mound, which is one of the attributes of ancient settlements. Ruins of adobe structures were found over a significant area. A large amount of ceramics from the 13th—15th centuries was discovered in the plowed fields. The collected materials and the entire complex of signs allowed P. N. Kozhemyako to suggest the identification of the settlement of Kara-Dzhigach with one of the Christian villages. It is now very difficult to establish the location of the Christian settlement, as more than five hundred years have passed since the Nestorion community ceased to exist here. Part of the population perished from the plague that ravaged the area twice, and part left forever, unable to find support in the struggle against strong opponents—Islam and Buddhism.

In general, there is no reliable information about the last period of the life of the Nestorions and their disappearance from Semirechye, although some sources report that the remnants of Christians were swept from this land by the storm of Tamerlane, which passed over Central Asia in the 14th century. On the other hand, it seems to us that the local tribes that adopted Christianity and individual representatives of communities, in the prevailing circumstances, adapted and dissolved among the local population, thus severing the last thread that connected Nestorionism with the vast Turkic world for several centuries. However, information about Christians in Mavarannahr and their struggle with Muslims in Samarkand can be traced until the first half of the 15th century.

We find mentions of the Tarsa-Christians in the epic "Manas":

...When the sun sets —

They say the Kyrgyz girl is beautiful

On the side of the Oi there are Tarsas,

Beyond them are the Persians...

To hold races at funerals —

An interesting custom among the Kyrgyz.

In the lowlands live the Tarsas,

Closer to here live the Persians...

Nestorion epitaphs are not only valuable historical and cultural monuments but also important linguistic sources. The Turkic lexicon of these texts reflects the dialects of the Turks of Semirechye, with the oldest layers likely dating back to the Karakhanid era,

Words such as sakysh ‘counting, enumeration’, alkyslyq ‘blessed’, yarlyq ‘command, order’ are found in written monuments of the Karakhanid period, particularly in the "Divan" of Mahmud Kashgari and in "Kutadgu Bilig" by Yusuf Balasaghuni (11th century). However, in these works, we do not find the words uzut ‘soul of the deceased’, yirtunchu ‘surface of the earth, world’, which are recorded in the Turkic texts of Nestorion monuments. Apparently, they did not exist during the time of Mahmud Kashgari.

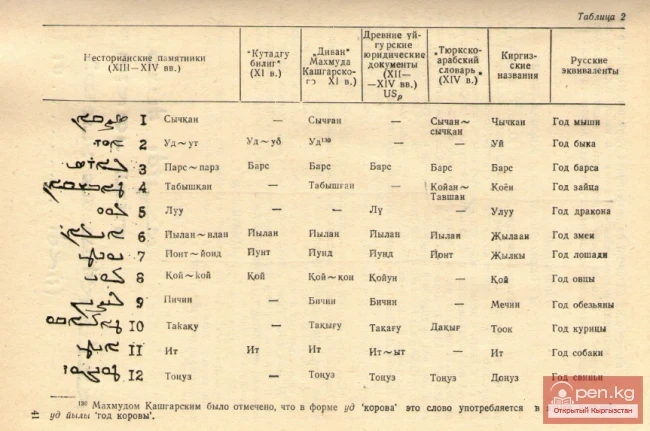

As is known from the inscriptions on the monuments of the Turkic Nestorions, a specific set of Turkic lexemes and expressions is used in the composition of epitaphs. At the same time, all the ancient Turkic names of the twelve-year animal cycle are attested in these texts (see Table 2).