Kyrgyz Folk and Mass Musical Creativity

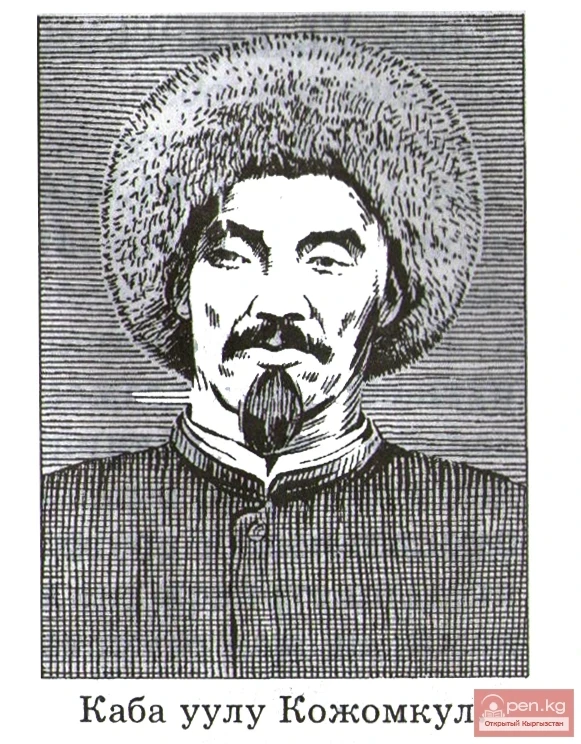

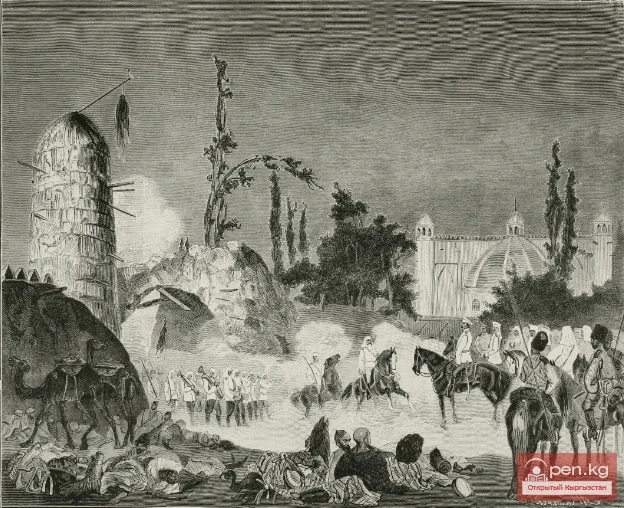

In Kyrgyz folk and mass musical creativity, songs about historical figures and events have hardly developed as an independent genre. History was widely covered in both large and small epics, but the images of legendary leaders and heroes were presented in a generalized-mythological manner. Real historical figures — such as khans Shabdan and Ormon, datkas Kurmanjan and Alymbek, heroes Balbai and Kozhomkul — more often became the subjects of akyn songs than of vocal mass folklore. Major historical events occurring at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries (the annexation of Kyrgyzstan to Russia, popular uprisings, etc.) may have been reflected in historical songs or poems, but there is currently no reliable information about them.

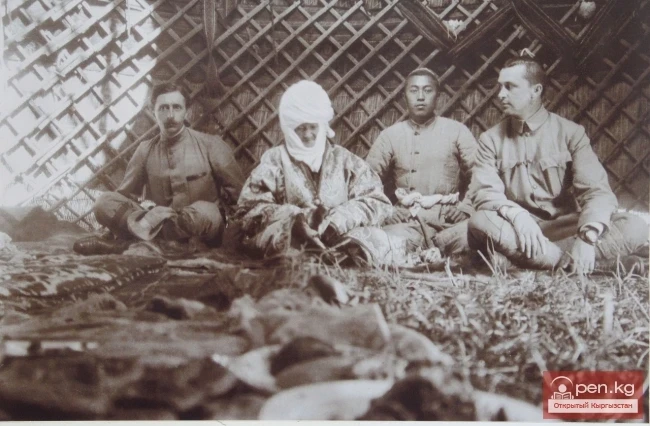

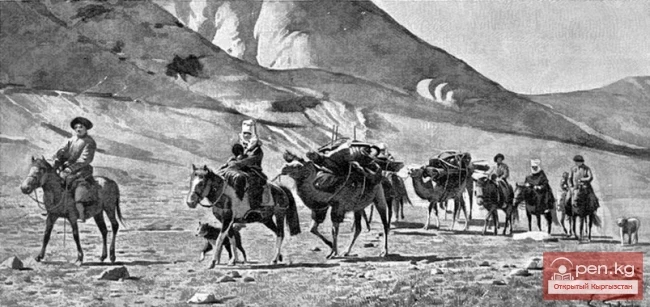

Philologists have recorded several works of folk historical poetry during field expedition work. Below is one example:

O, hero, may you remain in the rank of aji! You have been a khan for forty years,

And when you went to the holy Mecca,

We wished for you

To return safely to your homeland,

To see your people again.

These verses were composed during the Kyrgyz people's uprising in 1916, evidently for a funeral lament — "koshok" — on the occasion of khan Shabdan's death.

A. Zataevich notated two historical folk songs: "My People" ("Sen elim") and "Free Path" ("Erkin jol"). “'Sen elim',” he writes in a comment, “is a revolutionary song from the pre-October period to the tune of the old song 'Shol-akem'.” Thus, we have one of the rare examples of a historical song that emerged as a new subtext of a folk melody.

The genre of historical song found its place in mass and individual musical-poetic creativity during the Soviet period, which was influenced by the new ideology. Historical songs from this period can be divided into two types.

In the songs of the first type, the socio-political theme was embodied through the means of traditional Kyrgyz melody. Songs about the revolution, homeland, the CPSU, Lenin, Stalin, the Komsomol, the Soviet Army, about collective farms and factories, and Soviet holidays, despite their "thick" ideological content, were accepted by listeners largely due to their melodic beauty and performance by folk singers.

The well-known song-poem "28 Heroes" is an example of the historical genre, where a new theme is embodied in epic recitative. Kalmbet Erkebayev sings this composition, dedicated to the heroic feat of the Panfilov Division near Moscow, in the recitative style of the epic "Manas." The text belongs to the poet Aaly Tokombaev.

Historical songs of the second type are based on an updated melodic style, which is also influenced by other national cultures.

The march song, having seemingly taken the baton from the traditional march-like leitmotif of the epic "Manas" and the march element of Toktogul's "kerbezes," entered Kyrgyz song culture (and not only folk) in the 20th century. Previously, the march genre was not characteristic of Kyrgyz folk songs — unlike, for example, Russian or German. The process of adapting the march was not simple: there were no performance skills, and the irregular rhythm characteristic of most songs resisted the clear meter of the march. This genre had no social foundation among the Kyrgyz, with their traditionally nomadic and semi-nomadic lifestyle.

The overall political situation in Kyrgyzstan was more isolated from revolutionary Russia than in neighboring Kazakhstan, where, according to B. Yerzakovich, songs like "Kazakh Marseillaise," "Kazakh International," "Kazakh Varsovians," and others were already common.

Hamza Hakim-zade Niyazi in Uzbekistan and Saken Seifullin in Kazakhstan translated Russian revolutionary songs into their languages and created national examples in this style.

In the second half of the 1920s, the process of creating Kyrgyz Soviet march songs began in Kyrgyzstan — old songs were performed with new lyrics, and new verses and melodies were also composed. Concert programs of amateur artistic performances necessarily included choral patriotic songs, as required by the times. The rhythmic and intonational structure of the march and the new themes became increasingly familiar. A significant contribution to the formation of the new song style was made by members of the musical and choral circle of the capital's Pedagogical Technicum: K. Zhantoshev, A. Maldybaev, M. Elebaev, Z. Bektenov, S. Sasykbaev — the first generation of outstanding figures in the musical, literary, and theatrical arts of the republic.

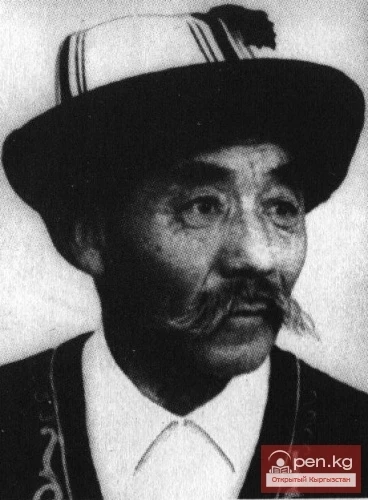

It is particularly important to highlight the role of Abdylas Maldybaev (1906—1978), who actively participated in the formation of a new song culture, both folk and later professional composition. His songs, based on the verses of various poets, possess a vivid folk character, as they were composed with reliance on the traditional intonational vocabulary. Many of them gained widespread popularity.

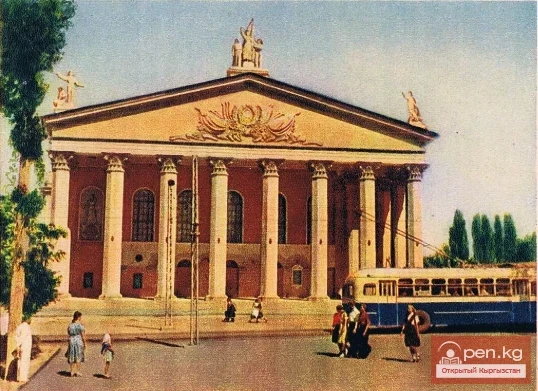

A. Maldybaev progressed from a self-taught musician to a professional composer and singer, a People's Artist of the USSR (1939), and a laureate of the Toktogul State Prize (1970). His work encompasses many vocal genres of oral and written tradition — from songs to oratorios. In 1929, Maldybaev graduated from the Frunze Pedagogical Technicum, and since then, his life and work have been connected with the Kyrgyz Musical Drama Theater, later the Opera and Ballet Theater, which was named after the composer.

Having begun composing his melodies in the early 1920s, Abdylas always responded to the most pressing themes of the time in his work. During his studies, he created the songs "Farewell at Dawn," "Red Banner" to the words of K. Zhantoshev.

This was followed by "The Killers," "Life Blooms" ("Gul turmush") to the words of J. Bokonbaev, "Red Scarf" ("Oy, kyzy joolukchan"), which soon became truly popular. In the 1940s and 1950s, Maldybaev studied at the Moscow Conservatory and continued to compose: "Life" ("Omur") to the words of Toktogul, "Who Shall I Tell?" ("Kimge aitam?") to the words of A. Tokombaev, "Just Like That" ("Myna, mintip") to his own words, "Dream" ("Tilek") to the words of J. Turusbekov, "Girl's Song" ("Kyz burak") to folk words, and many others.

In total, the composer has about 400 songs. The soulful warmth of lyrical melodies, the clear pace of marches, and the sparkling colors of humor in youthful and children's songs are presented in Maldybaev's compositions in conjunction with the expressiveness of folk melody. Maldybaev created the Kyrgyz romance and made a significant contribution to choral culture. Many of his melodies became integral parts of the dramaturgy of musical dramas and operas created in collaboration with V. Vlasov and V. Fere. These include the classic national operas "Aichurek," "Toktogul," "Manas." In this same creative partnership, the first State Anthem of the Kirghiz SSR was created.

Possessing a soft lyrical tenor with elements of folk timbre, Maldybaev the singer successfully performed in both folk and operatic repertoires. He sang leading roles and created memorable characters in many performances of Kyrgyz and foreign composers.

A. Maldybaev is a prominent musical and public figure, a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and the Kirghiz SSR, and for about 30 years he headed the Union of Composers of Kyrgyzstan. He has been awarded many orders and medals.

The development of the new march genre was facilitated by the establishment of radio broadcasting in the republic in 1930, which transmitted Russian revolutionary and Soviet mass songs. One of the authors of march songs of a patriotic nature was Mukai Elebaev (1906—1944), a well-known writer, poet, and playwright. He is the author of the songs "We Will Destroy the Enemies" ("Jo'yobuz dushmandy"), "Path to Freedom" ("Erkin jol"), "Song of the Proletarian Laborers" ("Zhalchylardyn yry").

In the post-war period, the march song of the outstanding akyn and yrchy Atai Ogonbaev (1900—1949) "Er Panfilov," composed under the impression of the feat of the Panfilov soldiers near Moscow in 1941, gained mass popularity. The author performed it with his own accompaniment on the komuz, and it often sounded as a unison mass choral song. It clearly exhibits features of the style of modern march songs, which successfully combine with the inherent properties of akyn recitatives — "terme."

From the first years of building a new national culture in Kyrgyzstan, the picture of vocal genres became heterogeneous. The number of authors composing and performing new songs in the genres of oral professional creativity began to grow rapidly. Their connections to folk traditions vary — from direct to mediated.

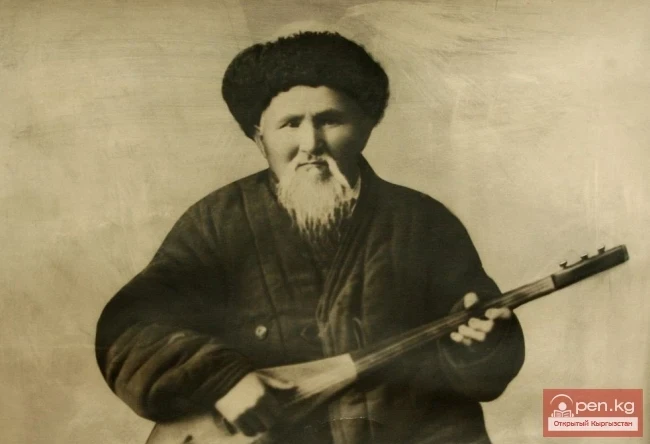

The first generation of folk authors includes akyns and yrchy who gained fame at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. These are Toktogul Satylganov, Musa Bayetov, Atai Ogonbaev. The creativity of these heirs of the song traditions of famous yrchy of the last century (Boogachy, Musakana, Syrtbai, Kalmurata) reflected the new time while remaining traditional in style.

The second generation is represented by Kalmurad Nurdoolotov, Zholaman Chorobaev, Asanbek Zhantemirov, Abdrashit Berdibaev, Bektemir Eginchiev, Abdykaly Temirov, Ekiya Mukambetov, Kanymbubu Dosmambetova, who laid the foundations of the new Kyrgyz folk song. Particularly notable figures of this generation were Abdylas Maldybaev and Jumamudin Sheraliyev. Their vocal creativity represented a transitional stage from the professionalism of oral tradition to written professionalism, that is, to composed song. They were the first to start valuing their melodies.

Songs created by authors of the second generation are characterized by a wide range of genres: patriotic, labor, lyrical. The stylistics of the songs is based on folk foundations and also incorporates features of the genre of Soviet mass song in its many varieties. These songs were performed not only by their authors, unison, accompanied by the komuz, but also in numerous arrangements made by P. Shubin, A. Zataevich, V. Vlasov, V. Fere, and other professional musicians in the 1930s to 1950s.

The third generation includes songwriters whose creativity developed from the 1960s: Sultan Mambetbaev, Bolotbek Abylgaziev, Maadanbek Almakunov, Rysbay Abdykadyrov, Aksuubai Atabaev, Zhenishbek Shamsheiev, Kudaybergen Temirov, Usen Sydykov, Mukhan Ryskulbekov, Kalaybek Tagayev, Sardorbek Jumaliev, Tugelbay Kazakov, Tokon Eshpaev, Soviet Urmanbetov, Turgunaly Nurmatov, Chubak Sataev, and others.

Among them are representatives of various professions, including musicians with secondary and higher specialized education (excluding composition). Many play some musical instrument — more often the accordion, bayan, and less frequently the komuz, guitar, or piano. They usually sing and play by ear.

The art of modern obonchu has absorbed certain properties of folk vocal tradition, amateur creativity, and compositional thinking. This type of musical activity has no clear boundaries and can be called semi-professional.

Musicians of this type are now referred to as melodists or obonchu jana atkaruuchu (literally, "author and performer of melodies").

The songs of melodists are extremely popular in the republic and pose serious competition to the works of professional composers of Kyrgyzstan, which is characteristic of the culture of Central Asian countries. This circumstance compels a close examination of the phenomenon of melodist creativity.

One cannot help but notice some commonality between the works of Kyrgyz songwriters of the third generation and the creativity of "bards" and other amateur authors of the USSR — CIS, working in the genre of "author's song." They share the ability to respond directly to the spiritual and aesthetic demands of the modern mass listener, the relevance of personal and social themes in songs, the semi-professional nature of creative activity, the predominance of solo performance forms, where the author accompanies their singing, the oral character of creativity, as well as a keen sense of the intonational vocabulary of the era.

At the same time, for Kyrgyz musicians, unlike modern Russian "bards," the priority is not the poetic word, but the melody. The lyrics of their songs are often written by professional poets.

As is known, vocal style, performance manner, and stage image in general are an integral stylistic feature of the "author's song" genre. Therefore, an important component of melodists' creativity is their interpretation of their own songs.

Each new generation of folk songwriters develops creative traditions in accordance with the artistic requirements of their time and paves the way for the further development of national song culture.

The melodists of the current generation possess a different, synthetic auditory background compared to their predecessors. Radio, television, cinema, and the video industry enrich their arsenal of expressive means. Major-minor scales and clear rhythm, homophonic-harmonic thinking replace the previous monodic, verse structure replaces the strophic, and the accordion or bayan as an accompanying instrument have significantly changed the appearance of modern Kyrgyz folk song. An example is the popular lyrical song by Asan Kerimbaev "Where Are You, Munara?" ("Mundashym Munara").

The repertoire of melodists is primarily composed of lyrical genres. There are many songs of a "motor" and dance character, which correspond to the active leisure of modern youth. Among many examples of this kind are "We Invite You to the Wedding" ("Toyubuzga kelgile") by A. Seytkaziev, "Congratulations on Your Birthday" ("Kuttuktap tuulgan kunundy"), by Sh. Duyshenalieva, "New Armenian" ("Zhaicy arman") by Ch. Satayev, "Thirst" ("Etso") by T. Nurmatov, "Twentieth Spring" ("Zhiyrmanchy zhaz") by T. Kazakov, and others.

The modern wave of songs has been enriched with new genres. Mixed-type songs have emerged, combining the styles of different genres. The auditory world of the modern person, thanks to mass media communications, can be called "planetary." And melodists consciously or intuitively complement the national singing style with intonations from other musical cultures, such as Uzbek, Kazakh, Russian, Italian, and Indian.

Thanks to new expressive means reflecting images of modernity, the songs of melodists differ significantly in style and content from ancient folk songs. They constitute a new type of national urban-rural youth song folklore, aimed at a broad audience.

At the same time, it should be acknowledged that the songs of melodists carry a number of stylistic contradictions. Only a certain portion of the songs possesses artistic value — an organic combination of poetry and music, individual and mass, national and non-national, traditional and modern. Nevertheless, many rather mediocre examples of the genre also find their admirers among listeners with unpretentious musical tastes.

Thus, the varieties of modern Kyrgyz song creativity — marches, waltzes, lyrical (new "sekhetbay," "kuy-gen," "arman"), humorous, and other songs — constitute a sufficiently active genre layer on the forefront of mass musical culture and are the result of the development of national song from its origins to the present day.

The above allows us to define this yet-to-be-finalized genre mass as songs of a new stylistic type.

In the 1980s and 1990s, amateur and professional musicians organized vocal-instrumental ensembles in the style of the West with their own repertoire, in which songs of the new stylistic type and folk arrangements occupy a certain place.

Thus, Kyrgyz folk songs are united into a large and multifaceted genre layer. They demonstrate not only external diversity of genre varieties but also internal interaction and mutual penetration of musical-poetic images and structures.

Being one of the bright and concise means of artistically-aesthetic reflection of the everyday life and emotional world of the Kyrgyz, the folk song genres discussed in this chapter continue their creative life in the modern era. In new socio-cultural conditions, they serve as links in the historical development of the national musical and poetic culture of the Kyrgyz people.

Recording from 1903, Semetey by Kenzhe Kara