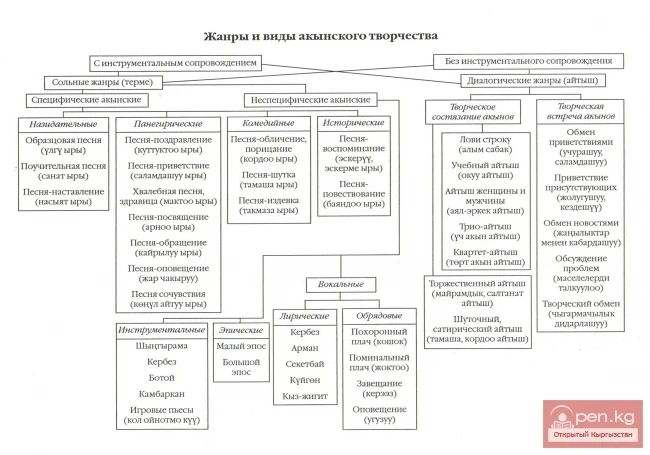

The genres of song lyricism are richly represented in Kyrgyz folk art, being among the most widespread, developed, and popular. Despite the variety of content, these genres share many commonalities, which give them stylistic unity and emotional kinship. Often, the same melody—“obon”—“migrates” from one lyrical song to another and is performed with new lyrics. For instance, the tune of “Oh, dear girl” (“Oy, asyl kyz”) is almost exactly used in the songs “Tea” and “To the collective farm friend” (“Kolhozdogu kurbuma”).

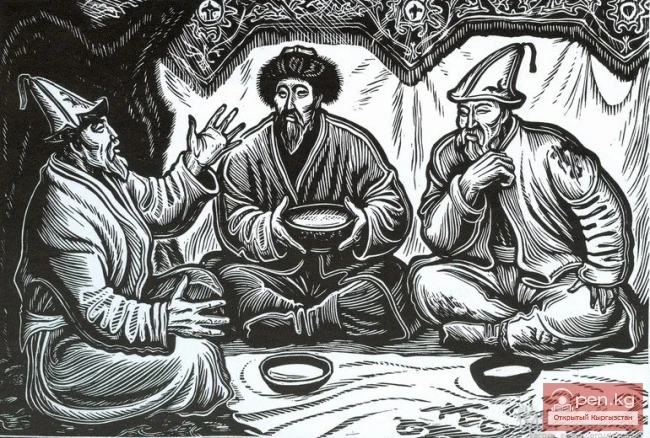

Lyrical songs are performed both without instrumental accompaniment and with the accompaniment of the komuz. The first type of performance is mass-oriented. Without accompaniment, the song is most often heard at traditional gatherings and family celebrations—so-called “joro,” “oturush,” “sherine,” during the song relay “sarmerden” and “yr kese” (“singing bowl”). Here, every attendee is expected to sing at least one pre-learned song.

Since the inability to sing is considered a shortcoming, every Kyrgyz strives to master singing skills, allowing them to perform primarily songs of a lyrical nature. It is not necessary to have a special poetic talent for this, as there are many popular songs in the folk environment; one only needs to choose at least one of them, learn it, and memorize it.

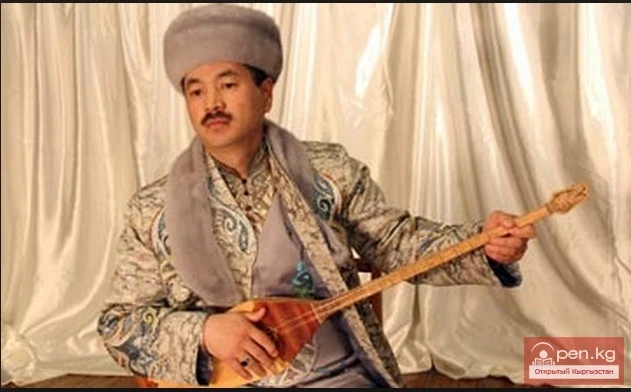

The second type of lyrical genre existence is professional. This involves singing songs with accompaniment, primarily accessible to folk singers—yrchy.

Yrchy are not only the best interpreters of well-known folk songs but also authors of their own. It is noteworthy that all folk singers and akyns of Kyrgyzstan who embarked on the path of professional musical creativity began their activities by mastering lyrical genres.

The development of the genre was influenced by the socio-cultural situation. In the past, songs were created in unity of word and melody and exclusively in oral form, but starting from approximately the 1930s, lyrical songs began to be composed to the ready-made verses of professional poets. Various options for synthesizing traditional oral musical creativity and modern poetry emerged.

The changed lifestyle gave rise in the 1930s and 1940s to new themes, which found expression in Kyrgyz vocal lyricism. Images of a beloved girl and a lovesick young man were often combined with ideals of camaraderie, mutual assistance in labor, etc.

Love song lyricism is denoted by the term ashyktik yrlary or suyuu yrlary. Three lyrical songs that gained mass popularity in the past—“Seketbay” (“Dear”), “Kuygen” (“Burning with love”), and “Arman” (“Cherished dream”)—over time became the progenitors of three genre subgroups, each of which included closely related song variants that differ in text and melodic details. Thus, each of the titles refers simultaneously to a specific song and to a song genre.

Here we deal with one of the specific principles of oral musical creativity, which operates not only in the sphere of vocal lyricism: a song that has become popular becomes a genre canon, within which individual creative solutions are inscribed, bearing the imprint of time, situation, and performance style. A song-genre emerges.

The most popular song genre is seketbay. This name has become synonymous in the folk consciousness, symbolizing a bright beginning in love.

Recognized seketbaychy—authors and performers of songs of this type—in the 19th century included Boogachy, Abdrakhman, Sirtbay, and Musakan. In the 20th century, their number increased.

Many examples of the “seketbay” genre are found in the collections of A. Zataevich, V. Vinogradov, A. Maldybaev, M. Abdrayev, and S. Yusupov. As an example, we present the love song “You are my joy” (“Tatsam ee tattyu balyndy”):

I cannot take my eyes off you,

There is no one more beautiful than you in the world,

Your sweet rosy face—

Like the work of a master’s hands.

The song consists of three verses (here the first is presented). Each includes four different melodic-verse phrases, organized on the principle of summation, where the third and fourth are syntactically connected. This tendency towards merging reflects the typical properties of lyrical “obons”—continuity of intonation, unity of melodic line. At the same time, this example illustrates another characteristic feature of lyrical song genres: the intonational development is based on the idea of not only similarity (the principle of variability) but also novelty. The presented song is performed with the accompaniment of the komuz.

In “seketbay” songs, elevated epithets, metaphors, and symbolic images are often used. The singer, expressing a passionate, sincere feeling, resorts to poetic comparisons. In the titles of most songs, there is usually either the name of a woman or some of her poetic characteristics—“Languid eyes” (“Boto kez”), “Dark-eyed” (“Kara koz”); sometimes the name of a flower or tree is given—“Red flower” (“Kyzyl gül”), “Red apricot” (“Kyzyl eruq”) or a typical emotional exclamation—“Oh, tobo,” “Oh-hoy,” “Oy-day.”

Songs that celebrate the beauty of the native land also belong to the “seketbay” genre. They bear the name of a locality, aail, mountain, pasture, or river. Well-known ancient folk lyrical songs include “White River” (“Ak-say”), “Tian-Shan,” “Talas,” “Free Mountains” (“Erkin too”), “Stretched Mountain” (“Kirme too”), “Chatyr-Kel” (the name of a lake), “Singing Bird” (“Sary barpy”), and others. The texts of such songs are often built on the basis of comparing images of nature and a beloved person, which allows them to be classified under the “seketbay” genre.

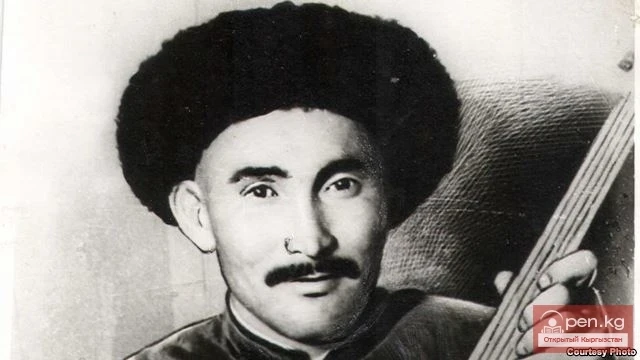

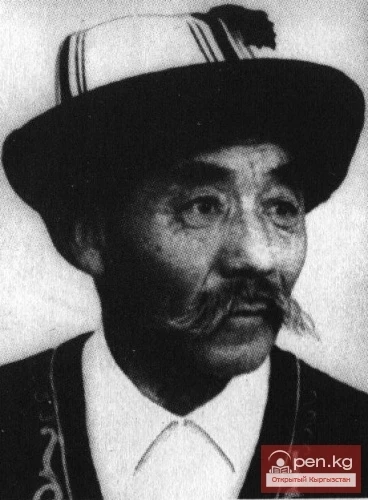

While “seketbay” sings of happy mutual love, the songs of the kuygon genre speak of unrequited love, “burned” (“kuy”—literally, “to burn”). The differences are noticeable both in the content of the poetic text and in its musical embodiment, in the character of performance. A clear understanding of them is provided by comparing two songs of the famous yrchy Atay Ogonbaev—“Esimde” (“seketbay”) and “Kuydum chok” (“kuygon”), the first of which sounds bright and serene, while the second is sad.