The so-called Great Epic is the main genre of the epic culture of the Kyrgyz people. The Great Epic, collectively titled "Manas," consists of several large parts named after the main heroes according to a genealogical principle. Each part is dedicated to the life and activities of representatives of one clan led by Manas.

Was Manas a historical figure? This question cannot be answered definitively. The Kyrgyz tribes, faced with the acute problem of unification and consolidation during the era of military democracy in the 7th-8th centuries, were led by a chief named Manas. However, the epic "Manas" is a work of a mythological type, summarizing a vast historical experience in collective symbolic images, of which the hero Manas was one. According to some sources, the events in Manas's biography are associated with the period of early feudalism, approximately from the 6th to the 10th centuries, when the Kyrgyz tribes fought against external and internal enemies to create a unified independent state in Central Asia.

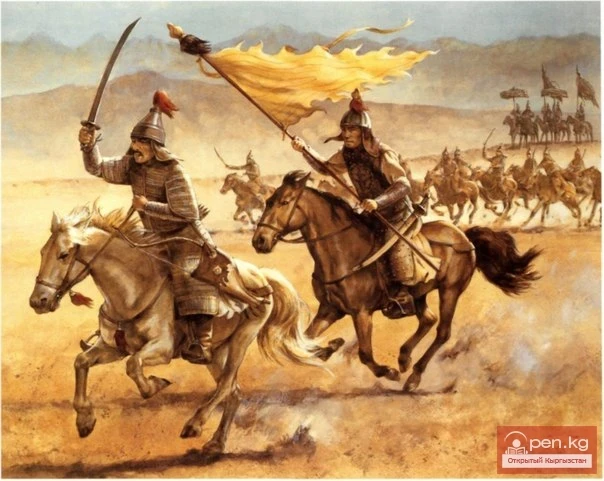

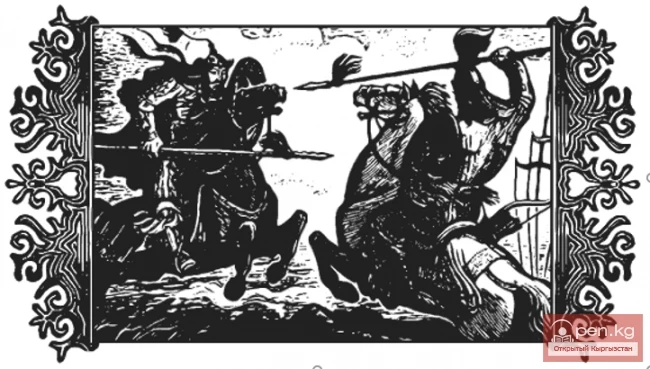

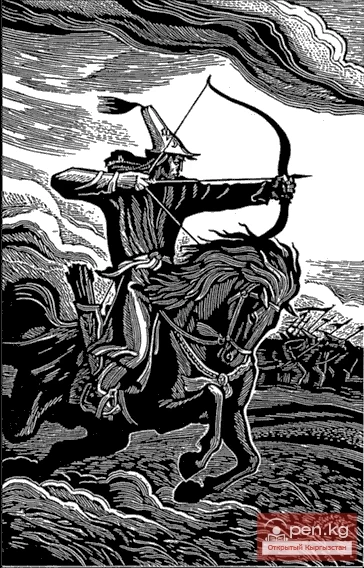

Manas is portrayed in the epic as a multifaceted character. In moments of battle, he is likened to a leopard or a tiger, while in times of peace, he is depicted as a magnanimous, kind ruler and a caring head of the family.

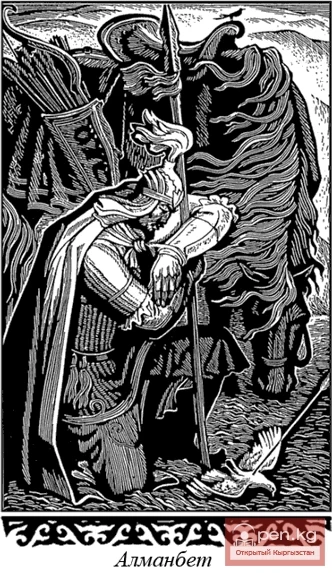

Surrounding Khan Manas were close companions: the elder Bakai — a wise advisor, his wife Kanikei — the daughter of the Persian khan, his friend and intelligent assistant, ally Almambet — of Chinese origin, Syr-gak — a loyal like-minded companion, and forty choro — reliable military leaders.

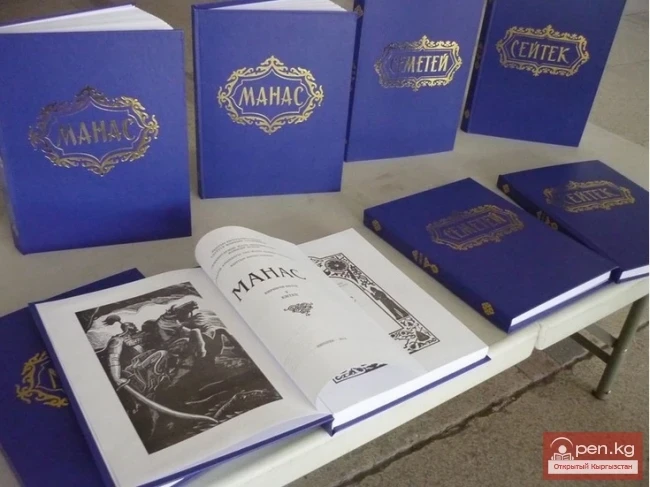

Manas's heirs were his son Semetey and grandson Seitak, who continued his legacy with dignity. Thus, the well-known epic trilogy consists of the main parts "Manas," "Semetey," and "Seitak."

An important principle of the epic's existence is its constant, unwavering development. The greatest storytellers introduce new episodes and facts into the epic. As a result, the epic expands both internally and externally, reflecting the musical-poetic thinking of each new era.

The third part of the Great Epic — "Seitak" — received a continuation in the 20th century. Sayakbay Karalaev recounted such "chapters" as "Kenen" (the son of Seitak), "Alimsaryk, Kulansaryk" (the grandsons of Seitak). Later, in the early 1990s, they were recorded from the student of S. Karalaev — Shaabay Azizov. The boundaries of the trilogy are also expanded by the manaschi-writer Jusup Mamay, who lives in the Kyrgyz Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China.

Chinghiz Aitmatov, referring to the epic "Manas" as an ocean, wrote: "The fact is that this genius and multilayered epic encompasses all aspects of the life of the Kyrgyz, including social life, love lyrics, moral and ethical issues, geography, medical, astronomical, and philosophical concepts of the ancients. And all this substantive diversity is in organic connection with the artistic form of the epic, the development of which began with fairy tales, myths, and fantasy and reached realism (in the folkloric sense), forming a single harmony."

The Great Epic was formed from smaller ones, as well as from numerous musical-poetic genres, and having acquired a new aesthetic quality, has been developing independently for many centuries (according to various scholarly estimates — from one to two thousand years).

Of course, the dominance of the Great Epic must have been preceded by a long process of development of the improvisational art of its storytellers — manaschi, semeteychi, seitakchi. The roots of these words point to the part of the trilogy in which the folk-professional storyteller specialized. The general term for this type of activity is "manaschi." This term was introduced into everyday and scientific vocabulary in the 20th century; in the folk environment, the storyteller was referred to as "jomokchu."

The special ideological and artistic significance of the epic and its storytellers in the life of the Kyrgyz people became evident, apparently, in the second half of the 19th — first half of the 20th century. This "truly epic period" (V. Radlov) found its most complete reflection in manas studies.

In volume, "Manas" (400,000–500,000 lines of verse) surpasses Homer's "Iliad" by 32 times, the Uzbek epic "Shahname" by four times, and the Indian "Mahabharata" by over a hundred thousand lines. The narration of one of the parts of the Great Epic could last days and weeks with short breaks. These unique instances have been preserved in popular memory. However, to this day, there has not been a single complete recording of the epic "Manas" from beginning to end. Currently, approximately 60 variants and sections of the Great Epic have been collected, performed by 60 manaschi. Despite all the differences in variants, their content, and performance styles, the epic-trilogy represents a single genre layer, the specificity of which lies in objective narrativity, large forms, and logical transitions of episodes-pictures.

"Manas" has a cyclical structure consisting of numerous sections with features of monologue, song, as well as imaginary dialogues, ensembles, and mass scenes. In it, in crystallized or diffuse form, lyrical, historical, ritual, comedic, akyn genres of musical folklore, as well as proverbs, sayings, riddles, fairy tales, and legends are found. In the process of performance, the specific epic recitative sounds with characteristic intonational archetypes of these genres.

The intonational composition of the Great Epic is a whole world of storytelling culture, a kind of anthology of Kyrgyz recitative. V. Vinogradov, who comprehensively analyzed Kyrgyz folk recitative, identified four different types, in which the poly-genre melodic style of the Great Epic is practically embodied.

The first type of epic recitative, as named by V. Vinogradov, is non-musical recitation (example 31). It is rarely encountered. It appears in those moments of narration when the manaschi, in excessive excitement, resorts to semi-conversational declamation and when musical intonation dissolves in the swift flow of "hot" speech. Therefore, this type of recitative is almost impossible to notate.

The second type of recitative has features of melodized declamation; it already fixes sound-height, metrorhythmic, and compositional characteristics (example 32). The sound range of the recitative most often corresponds to a trichord or tetrachord (of the Ionian, Aeolian, or Phrygian type), and the melodic phrase includes two to three lines of verse.

The third type of recitative is close to the second. It is clearer in terms of tonality; the musical phrases are more pronounced and correspond to one or two lines of verse. They end with a similar descending cadence.

Finally, the fourth type of recitative is a melodic recitation, in which the features of primary musical genres of Kyrgyz vocal folklore are often found.

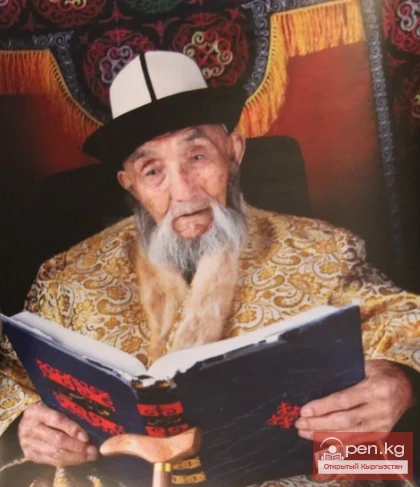

Essentially, the creativity of each major professional storyteller is an individual version of the Great Epic. The well-known Kazakh writer and literary scholar Mukhtar Auezov, who once studied the epic "Manas," noted the presence of two storytelling schools in Kyrgyz folk epic creativity: the Issyk-Kul and Tien Shan schools. The brightest representative of the former he considered Sayakbay Karalaev, and of the latter — Sagymbay Orozbakov.

Manas scholar R. Kydyrbaeva provides a different, more complete regional characterization of storytelling traditions. She established the existence of four regional groups of storytellers — from the Chui, Issyk-Kul, Naryn, and Talas regions. At the same time, the scholar emphasizes the conditionality of such division, as, according to her assertion, the development of epic folk culture proceeded in a mixture and mutual enrichment of various storytelling schools and performance styles.

On a larger scale, all Kyrgyz epic creativity can be viewed as two major regional epic schools: northern and southern. This division has a certain historical justification, as the formation and development of the Great Epic in the north and south of the republic occurred along different paths and in unequal social conditions. In the north, the active development of the epic took place in the context of a nomadic lifestyle, which persisted until the 1920s. In the south, where a sedentary agricultural way of life prevailed, by the 18th-19th centuries, the epic "Manas" had lost its significance.

The analysis of the epic is impossible without relying on its intonation in the live act of narration. Let us present the content of two episodes of the Great Epic in connection with their musical-poetic analysis.

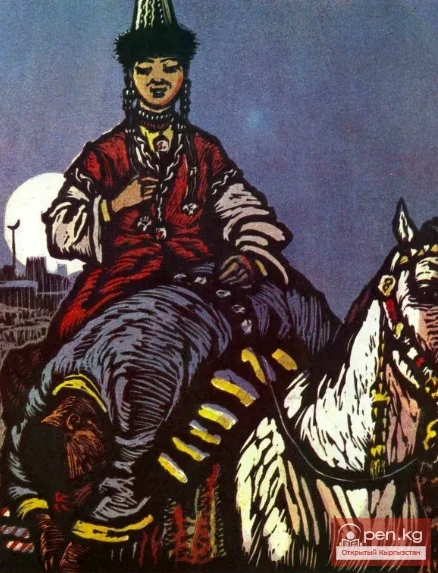

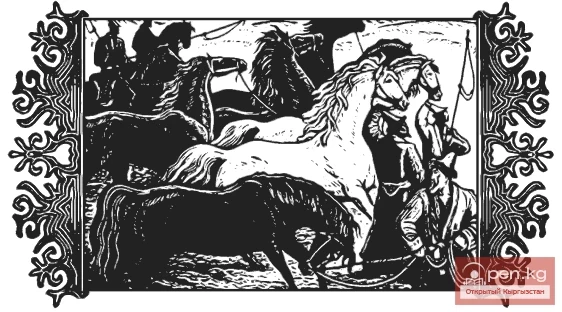

An episode from the second part of the trilogy "Semetey" is known by the title "Kanykeydin Taytorunu chabyshy" ("The Trial of Taytoru"), or briefly — "At chabysh" ("At the Races"). In this episode, recorded during the creative flourishing of Sayakbay Karalaev, his individual style and mastery are most fully manifested. In a dramatic and virtuoso fragment of the epic, one of the most popular folk-sport traditions of the Kyrgyz — horse racing — is described. The essence of the episode lies in the fact that Manas's widow Kanykey tests the maturity and endurance of the heroic horse named Taytoru, intended for her son Semetey, the future hero.

The colorful, lively nature of the races and the participants of the action are vividly described. The character of the heroic tale allowed the manaschi to maximally express the performer’s temperament in the rapidly developing improvisation. The storyteller narrates the deeds of long-gone days with feeling and epic grandeur, vividly recreating the thrilling picture of the competition. Those who listened to and saw Sayakbay Karalaev were left with the impression that the manaschi had been present at the scene of the events or had transformed into the one he was narrating about.

The entire episode consists of several sections, varying in scale and contrasting in rhythmic-intonational and tempo aspects. Melodic sections are juxtaposed with recitative ones. Moreover, the subsequent sections logically continue and develop the previous ones, thus creating an internal harmonious structure in the process of performing epic improvisation.

Despite the external fragmentary nature of the form, the episode is compact, whole, and sounds as if on a single breath. The specific formative factor in the structure of the episode is its mobile variability. There is a powerful action of the principle of free, spontaneous improvisational creativity, which is so characteristic of large genres and forms of traditional Eastern monodic culture. Not only poetic improvisation is free, but musical improvisation as well. The storyteller often resorts to expressive emotional exclamations, glissandi, and throat-nasal intonation.

The first section of the episode has the character of a slow introduction (the first 13 measures). The three-beat recitative sounds calm and measured, the storyteller's voice is even and smooth. But soon, intonations of anxiety appear in it, which are evidently the feelings of Kanykey herself.

The melody of the introduction is familiar to almost every Kyrgyz. Especially popular is that part of it, which (without surrounding and passing sounds) forms a typical outline for Kyrgyz folk vocal and instrumental music, with a neutral third, and in the form of a monody is classified as the fourth type of epic recitative.

This melody has become the intonational symbol of "Manas." All manaschi refer to it, and composers often use it as thematic "grain" in various genres of modern written musical culture.

The march-like, resolute, manly rhythmic intonation serves as a generalized-typical melodic formula in this episode, as it, individually interpreted in the creativity of various manaschi, aligns with the overall heroic content of the Great Epic.

The second section of the racing episode is prepared by a small wave-like phrase in the volume of a tetrachord. The tempo here is more mobile, with noticeable accentuation of the strong beats of the march-like rhythm. The tonal foundation of the second section is a pure fourth higher than in the first, demonstrating a "modulatory" process. The storyteller's voice covers a higher register. The change in the tessitura of singing raises the emotional intensity of the episode.

The third section is swift and dramatic. It describes the course of the race itself: the spectators tremble upon seeing Taytoru in last place. But this is just the beginning of the competition. The drama of the situation is manifested in the rubato rapid speech, sounding with great expressiveness in the range of a ninth with sharp rises and falls.

The fourth section is somewhat more restrained than the previous ones. The majestic march-like style does not last long. The tempo increases, the storyteller's voice is again excited. The epic melody is replaced by recitative, which this time consists of 15 lines of verse and is the most passionate and ecstatic. The great dynamic rise and tension of the sound allow this micro-section to be classified as the climactic zone of the entire episode. The overall range of the recitation covers an interval of two octaves due to exalted exclamations. This is a rare moment for epic creativity, indicating the uniqueness of S. Karalaev's performance style.

The fifth section is the longest and most impressive. It is the finale, the solemn resolution of the dramatic episode. The storyteller conveys the immense joy of Kanykey and all those interested in Taytoru's victory, narrating with special expressiveness the final moments of the race, how the heroic horse defeats its rivals, and how Semetey's relatives (Bakai, Kyrgyl, etc.) cheer Taytoru at the finish line with loud shouts. In this section of the episode, the emotional tone of the storyteller reaches its peak.

The poetic text of the racing episode is based on the traditional seven-eight syllable syllabic verse typical of Kyrgyz folk song culture. In S. Karalaev's performance, it is sometimes elongated, for example:

(Oh) what a cry (ka-ra-kuu) is heard from Kanykey

She is feeling bad, crying,

(At that time) the youth is growing up.

The bird called Kys-galdak

Does not return to its nest.

The poor Kanykey

Cannot find peace in her anxiety.

Tears flow from her eyes...

She grieves, like a wild duck,

That has flown forever from the nest.

She is afraid, the poor thing,

For her son.

The analysis of one of the episodes from the "Semetey" part shows that the genre of the Great Epic differs from other genres of Kyrgyz folk vocal culture by large contrasting-composite (V. Protopopov's term) improvisational forms, in which melodic development is built on the comparison of conditional modal tonalities, voice registers, and all four types of recitative.

It should be added that the intonational diversity and emotionally-expressive interpretation of the epic is a characteristic feature of the style of the Issyk-Kul regional school of storytelling, which extends to all regions of the republic and is picked up by performers of "Manas" from the middle and younger generations. The performance style of Sayakbay Karalaev can be easily traced in the performances of such manaschi as Kaba Atabekov (born 1920) from the village of Tort-Kul in the Issyk-Kul region, Urkash Mambetaliev (born 1936) from the village of Taldy-Suu in the same region, and Asan-khan Jumanaliev (born 1940) from the village of Talas in the Talas region.

The fragment of the episode "Manas's Great Expedition" ("Manastyn chon kazatka attanyshy") illustrates another type of narration of the Great Epic. The episode was recorded in the performance of Moldobasan Musulmankulov.

Musulmankulov narrates slowly, without haste. The moderate tempo, clear and precise intonation of each word and verse is a characteristic feature of his improvisation. The narration is rhythmically measured, relatively static, without emotional peaks. There are no sharp dynamic and agogic contrasts in Musulmankulov's tale. The main heroic melody-motif of "Manas" (the fourth type of epic recitative, example 34) sounds ostinato, with slight rhythmic-intonational variations. The manaschi rarely goes beyond the seven-eight syllable poetic formula.

The noted features of Musulmankulov's performance not only express his individual storytelling manner but also characterize the Naryn epic school.

Thus, the Great Epic is the largest, monumental heroic genre of Kyrgyz oral folk creativity, which lives in the traditional solo-improvisational art of singer-storytellers, in special theatricalized forms of recitative singing without instrumental accompaniment.