Narrow Mindset of the Kyrgyz Nomad

The proposed general scheme of the evolution of consciousness aims to show what horizons can be revealed by understanding the characteristics of historical types of consciousness in the study of Kyrgyz history and history in general. Let’s clarify this with specific examples.

Historical psychology is a young science, and there is still much that is unclear and undiscovered in it, so the first results of its application in specific historical analysis can only be more or less successful hypotheses. However, it is important to highlight the problem, the new approach, and the collective efforts of historians will undoubtedly lead to its successful implementation.

For a historian studying the past of the Kyrgyz, it is useful to know and take into account the historical features of their consciousness for a more adequate explanation of their social behavior at any stage of historical development.

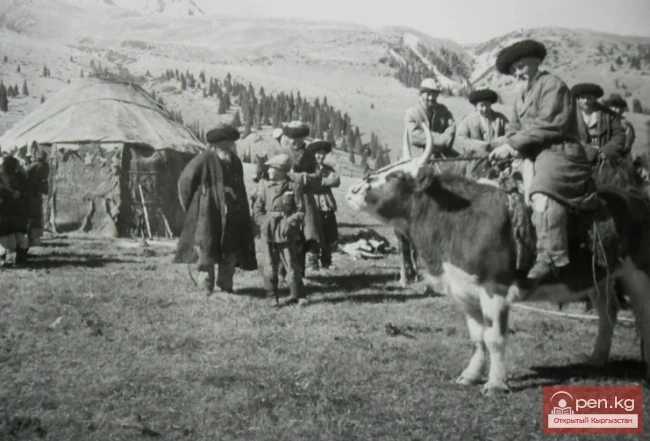

These features cannot fully explain the social behavior of the Kyrgyz or any other people, as it is also influenced by socio-economic factors. However, it cannot be denied that the characteristics of the group consciousness of Kyrgyz nomads had a special imprint on all their actions, and in some cases, understanding their behavior is only possible by considering the peculiarities of their perception and thinking.

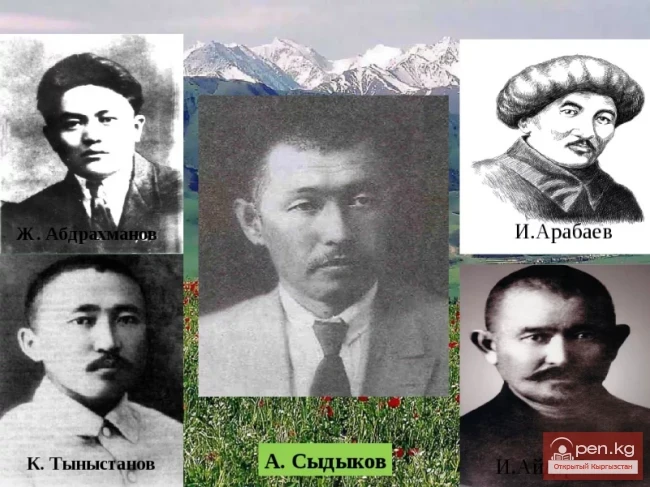

There is no doubt that during the pre-revolutionary period, as well as for a long time after the establishment of Soviet power, the Kyrgyz people as a whole were at the second traditional stage of historical consciousness, while some of its representatives, such as A. Sydykov, I. Arabayev, K. Tynystanov, Yu. Abdrakhmanov, and others, transcended this type of consciousness, primarily as a result of their education.

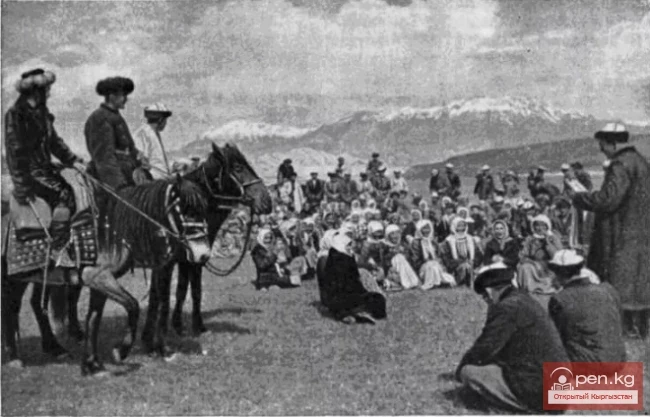

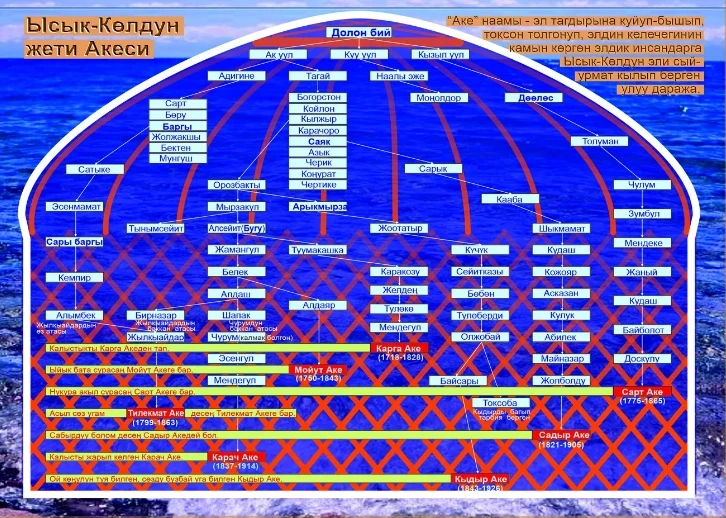

In the history of Kyrgyzstan, there is also the problem of self-proclamation and naive "monarchism." The uprising against the Kokand rulers was led by a simple man, Iskhak, who took the name Pulat-khan, or during the uprising of 1916 against Russian autocracy, the leadership belonged to Kyrgyz tribal leaders—manaps, many of whom at that time adopted the title of "khan." What caused this? This phenomenon in the history of Kyrgyzstan has not yet received a coherent explanation. Only an appeal to historical psychology allows for clarity on this issue. It has already been mentioned that people with a traditional type of consciousness, such as the Kyrgyz who lived during the tribal system, did not possess sufficient self-awareness. When rising up against their oppressors, the nomadic masses needed a sanction "from above" in the person of a tribal leader or khan. They led the movement because, in the perception of nomads, only they could become true leaders. If the leader was not such, he appropriated the title of "khan," as happened with the false heir to the Kokand throne, Pulat-khan.

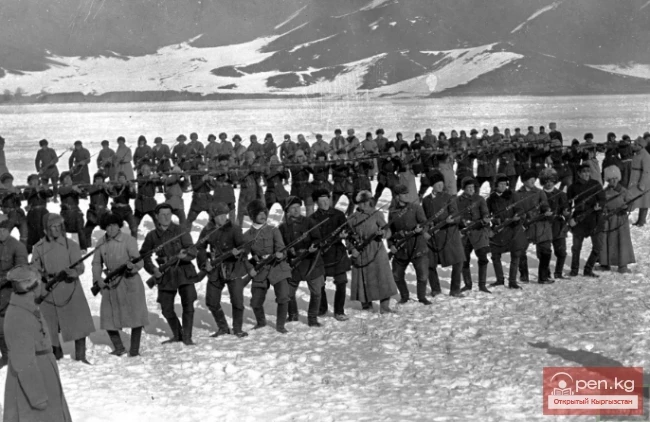

Otherwise, the masses would simply not follow him. Or, for example, another case. In the 1920s and 30s, party-Soviet leaders of Kyrgyz nationality, who came from the lower classes, typically began to dress in khan's attire, organizing "royal" outings surrounded by a lavish and numerous retinue. The Soviet power declared war on the bai and manaps, began to persecute and exterminate them, appointing people from the masses in their place. However, in the traditional consciousness of the nomads, they did not become true leaders. All this theatricality with dressing up pursued one goal—to gain recognition among the nomads as genuine leaders. However, such a policy did not achieve sufficient success. It was necessary to eliminate the manap class for the nomadic masses to recognize the new leaders. The dressing-up procedure was only unnecessary for workers from the manap environment, who preferred to wear simple commissar clothing (leather jackets, Budenovkas, gymnasterkas, etc.), as they had no issues with lineage. This also explains why the leadership of the basmachi units fighting against Soviet power consisted of representatives from the higher classes, as well as why Bolshevik agitation against the bai and manaps did not find understanding and support among Kyrgyz nomads.

All this was the result of the fact that the nomad did not distinguish himself and the people around him as an object of influence. The subjects of action in the form of a tribal leader, khan, mullahs, or otherworldly forces could influence him.

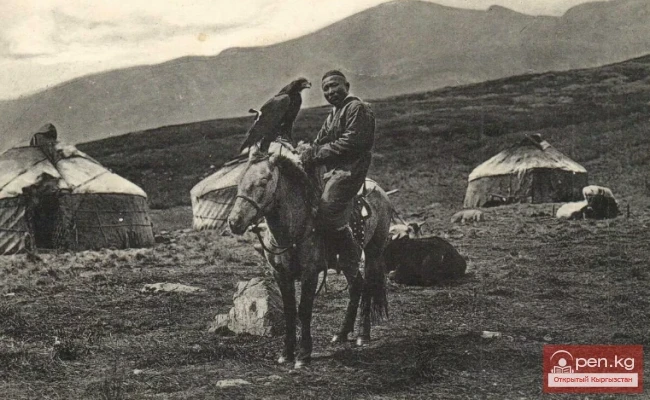

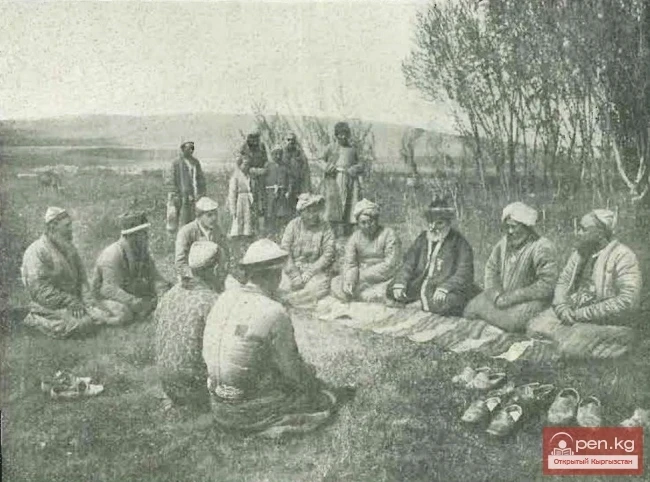

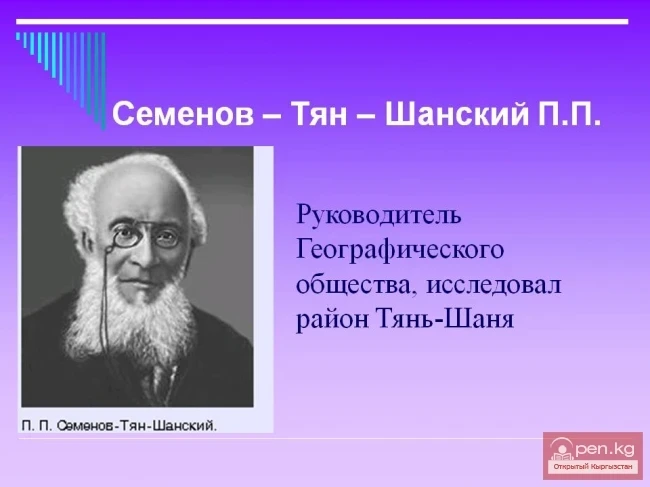

The Kyrgyz nomad did not know how to think sufficiently abstractly and generally. The narrowness of his worldview, the inability to psychologically detach from his small personal or aily practical experience, to see meaning in events occurring beyond his tribe, led to the fact that the nomad not only missed great historical events but sometimes did not even show interest in what was happening in the country. The capabilities of the nomad's psyche allowed him to have judgments exclusively about the objects and phenomena of the surrounding world.

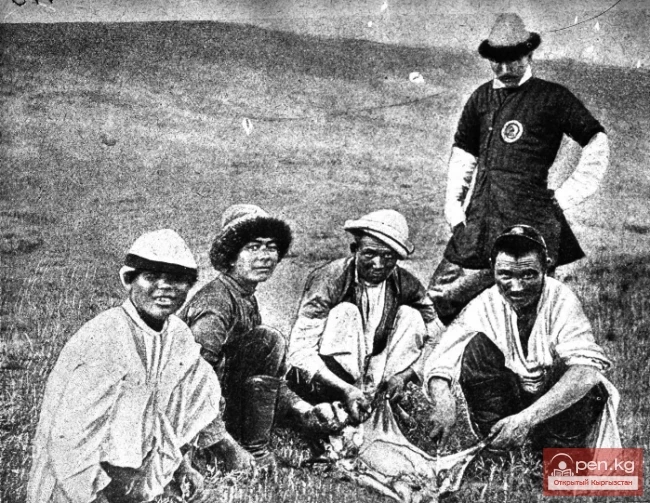

Everything that went beyond the boundaries of his individual experience could not enter his consciousness and be the subject of his consideration and understanding. In this regard, the only rare exceptions were the most educated layers of Kyrgyz tribal society among the representatives of the tribal elite, religious cult servants, the emerging intelligentsia, merchants, students of Russian-native schools, gymnasiums, and universities, and employees of the colonial administration. This explains why, in general, the Kyrgyz nomadic masses remained indifferent to the ideas of the proletarian revolution, while the most active participation, against the backdrop of the inert mass, was shown by representatives of the so-called "alien classes" and why they constituted the leading forces of both the counter-revolution and the basis of the Bolshevik political elite of Kyrgyzstan. This also explains why revolutionary events were limited to the territory of the European diaspora—district cities, coal mines, railroads, branches, and routes.

Transition from One Historical Type of Consciousness to Another in Kyrgyz Society