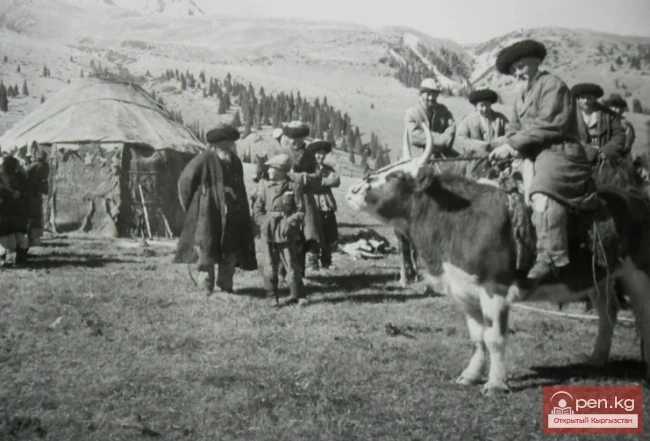

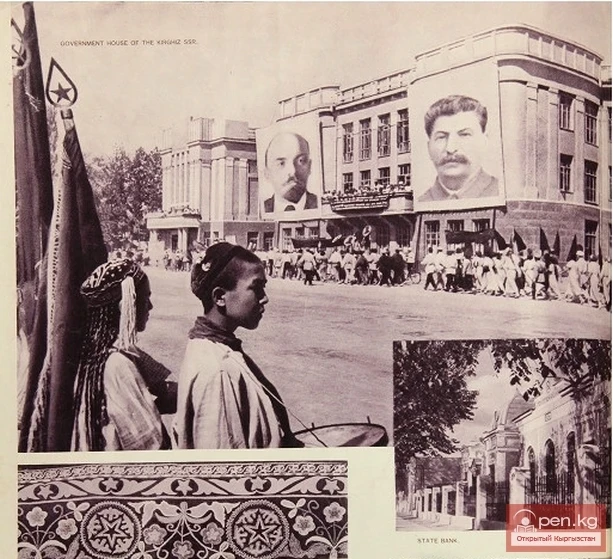

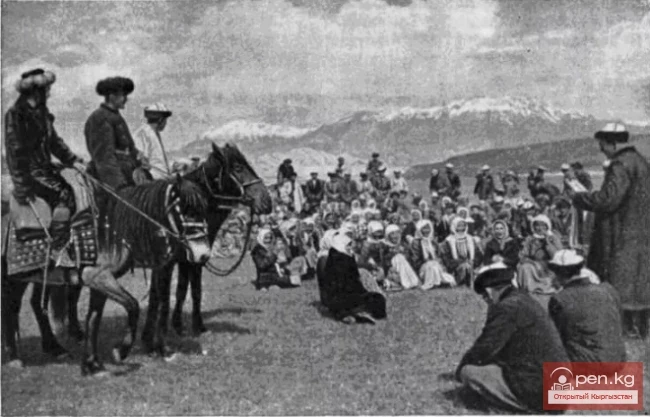

Kyrgyzstan in the 1920s. Introduction

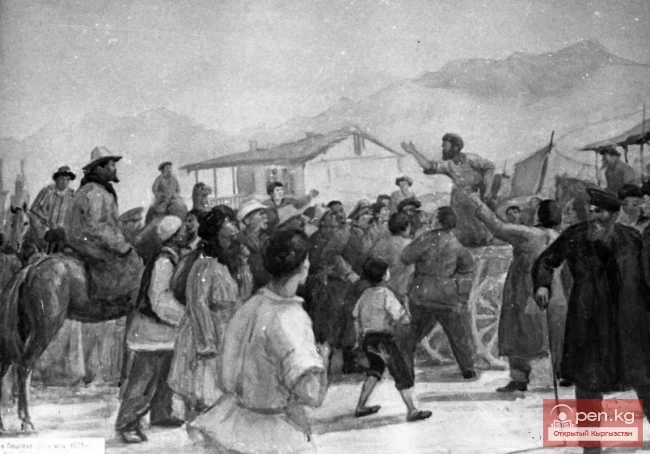

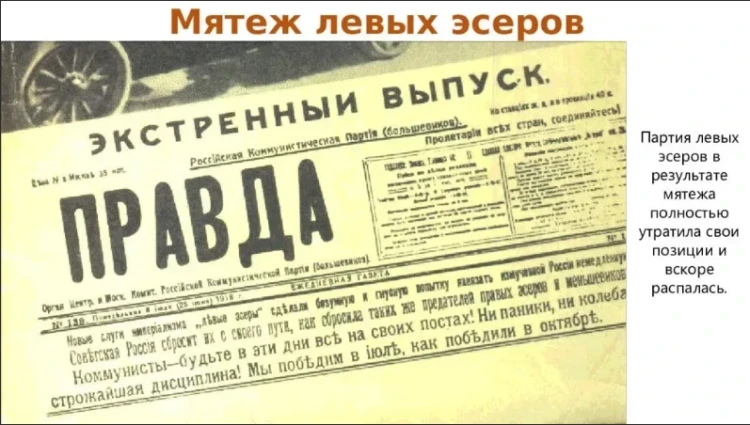

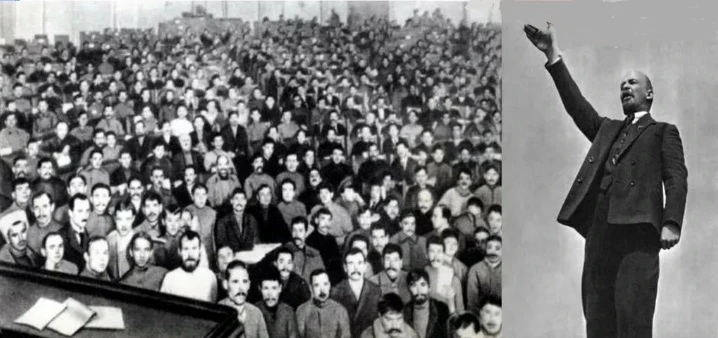

With the establishment of Soviet power, a political culture began to form and grow among the peoples now living in the new independent countries of the CIS, oriented towards a rigidly centralized state governance of society, with a pseudo-self-activity role of the public, as the Bolshevik-Communist party transformed into the backbone of a leaderist state system.

It was then that the initiative and creativity of people were replaced by the self-activity of the authorities, and real public activity was reduced to a state of imitation of the activity and protest of individual dissidents.

With the beginning of the democratization of the former Soviet society, the interests of various layers of society were legally and openly represented on the public stage, requiring attention to individual voices and the polyphony of the masses, integrating these interests, and seeking compromise solutions for their satisfaction. As a direct reflection of this process, many "informal groups" began to speak out loudly, and the phenomenon of "informals" formed in public consciousness. The emergence of the informal movement and its rapid growth both in depth and breadth laid the foundations for the revival of a multi-party system in the USSR and the formation of civil society as the most civilized form of human organization.

The civil movement declared its desire for full-fledged participation in the political life of the country. From the depths of the informal movement, numerous political parties and associations, public and other organizations emerged and became organized, aiming to develop various alternative ideas or complexes of ideas directed at the modernization of society. However, this pluralism of opinions rarely leads to tangible results, as both under communist and democratic regimes, it acts as an alternative to the official authorities. The very fact that the alternative movement remains unexplored (ignored by social sciences) indicates that the state and the officially established scientific, social, and political institutions have been unable to fully utilize the civic activity of the population. Accordingly, they not only do not accept public initiative as an additional reserve for implementing planned tasks and prospects but even directly oppose it, thereby generating active or passive protests and discontent from citizens, parties, movements, unions, etc. The main thing is to understand that alternative movements in our time, as a social phenomenon of a psychological order, are primarily connected with attempts by individuals to express their individual traits as fully as possible in society. Public activity manifests itself with particular strength in crisis moments, accompanied by a loss of trust in the authorities and a refusal to participate in official political life, leading to various forms of protest against it. In this positional conflict, there should exist an acceptable technology for resolving it through peaceful compromise aimed at developing a certain political and any other solution that does not hinder the development of the existing system.

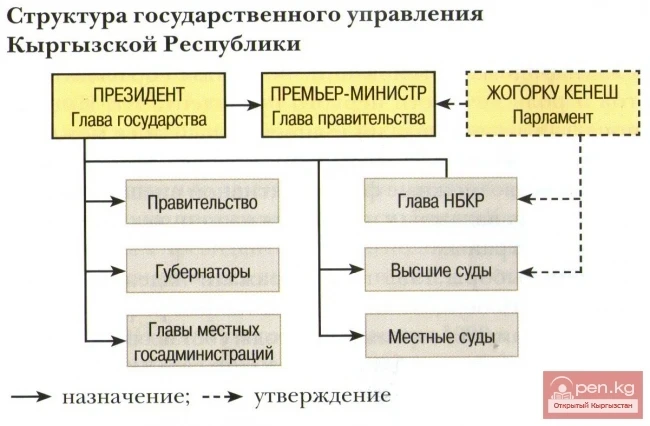

What has been said is directly related to the Kyrgyz Republic, where an intensive process of awakening society from the political addiction of Stalinism and the lethargy of stagnation times is underway. To date, more than 400 socio-political organizations have been registered here, including 15 parties. Some of them exist in opposition to the official power, protesting and criticizing it. Others, on the contrary, feel quite comfortable, using the formal system to their advantage, subordinating it to their own interests.

The awakening of civil society in the republic generates social processes characterized in science and politics as a "revolution of consciousness." The overall direction that these diverse, sometimes contradictory processes will take will depend primarily on the forms of social and state life that this revolution of consciousness will take and which trends will prevail within it. One visible indicator of this revolution of consciousness is the increased and sustained interest in the past of our homeland, especially in its unknown or carefully concealed pages. Never before has there been such a strong desire to eliminate "white spots," to see the intertwined fates of people in history, the emotionally colored picture of the constantly changing lives of the masses and individuals, because, as the French historian Marc Bloch wisely noted, "history is the science of people in time." This thought resonates with the philosophy emerging in our society, which places the individual at the center of the entire universe.

In the history of Kyrgyzstan, the most interesting and exciting pages are those that were under the ideological ban of the CPSU, where the history and fates of people are closely intertwined. There are still no answers to the questions: did the current Kyrgyz informals and oppositionists have their distant predecessors; what ideals, goals, and tasks guided them in their practical activities; were these ideas implemented by the official authorities; what was more in their work—positive or negative, etc.

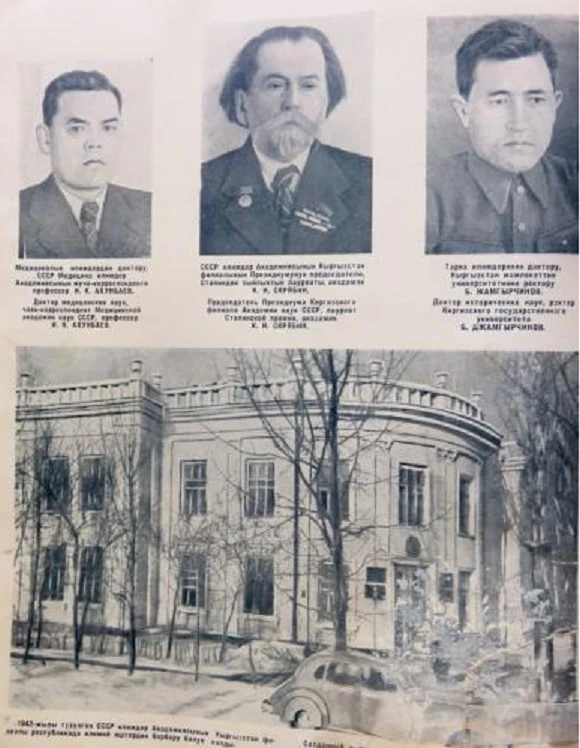

The satisfaction of the interest in the past and the creation of a truthful and multifaceted picture of the complex and contradictory historical development are still poorly supported by the substantial works of scholars. This is not surprising—the ideological stagnation in science has proven to be very prolonged. Previously published monographs, essays, and lecture courses are largely not free from falsification and errors and do not correspond to modern historical vision, which is based on scientific historicism, objectivity, creativity, and anti-dogmatism.

It cannot be asserted that domestic historiography was absolutely indifferent to the problem of opposition in general and intra-party opposition in particular. The fact that this was not the case is evidenced by numerous works on the history of the civil war and the Basmach movement, on the history of the White movement and counter-revolutionary uprisings and rebellions, on the history of Trotskyism, "worker's opposition," "new opposition," etc. Moreover, it can be said that domestic historiography exhibited, if not a forced, then certainly a militant-aggressive interest in the indicated problem. It showed extreme interest in ensuring that the study of this problem did not go beyond the ideological frameworks that were formulated in official historical and party publications, whose prototype was the "Short Course on the History of the VKP(b)." Any attempts, even the most timid, to reinterpret outdated "theories" and dogmas were immediately suppressed, and their initiators were punished, as happened with the legal scholars K. Nurbekov and R. Turguabzkov, who attempted in the mid-70s to justify the "nationalist" and "anti-Soviet" project of creating the Kyrgyz Mountain Region.

The textbook prepared by K. Nurbekov was banned and even removed from the libraries of the country.

The extreme secrecy and prohibition surrounding the problem of opposition made the study of this topic risky and dangerous.

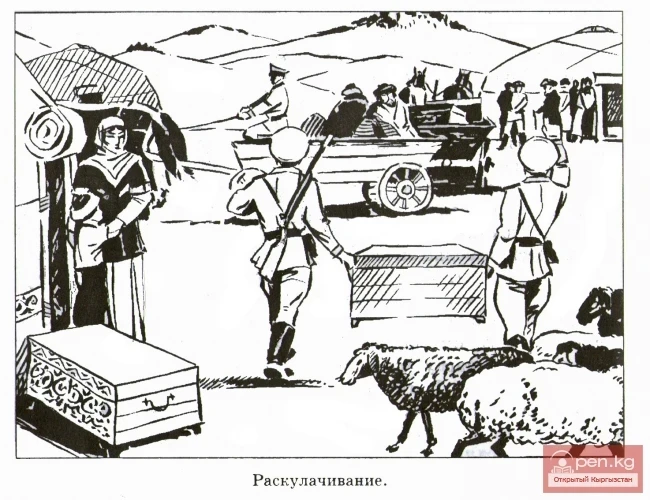

Therefore, it was doomed to stagnation and, in theoretical terms, remained at the level of concepts from the 1930s, when mass repressions against the so-called "enemies of the people" began across the country.