FEATURES OF HISTORICAL CONSCIOUSNESS AND SOCIAL BEHAVIOR OF THE KYRGYZ IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY

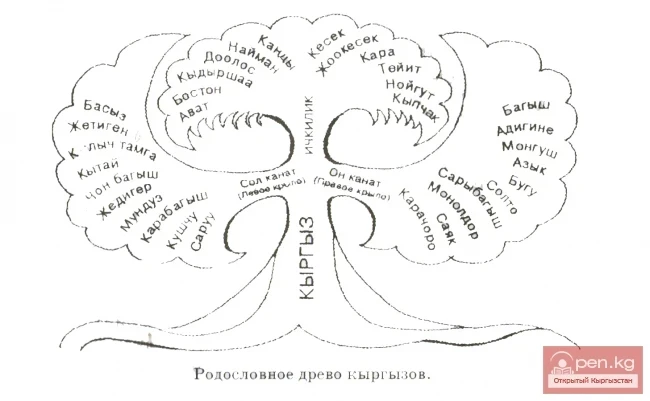

In addition to ideological, political, and socio-economic reasons, the crisis of historical science in Kyrgyzstan is also caused by the fact that our people, who lived before the Soviet era under a tribal system, did not have deep scientific traditions in studying their own history.

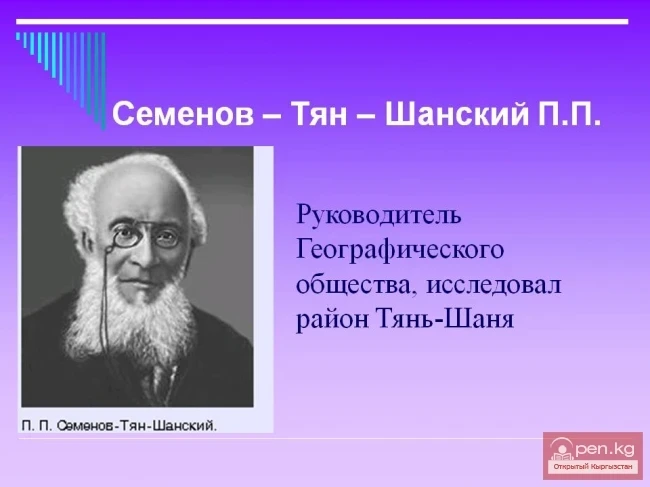

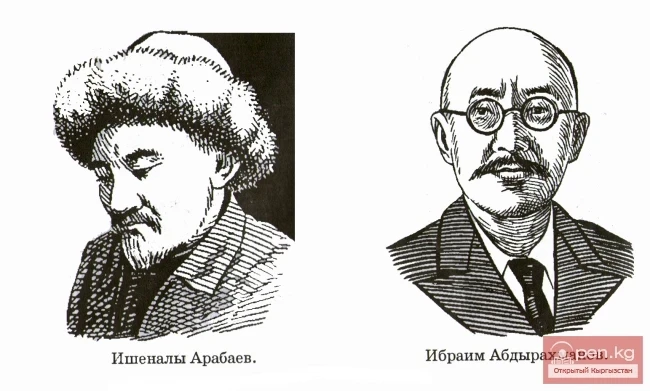

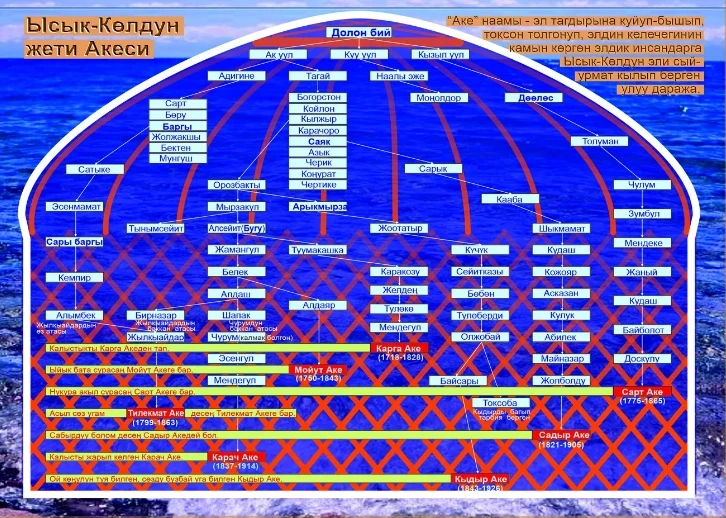

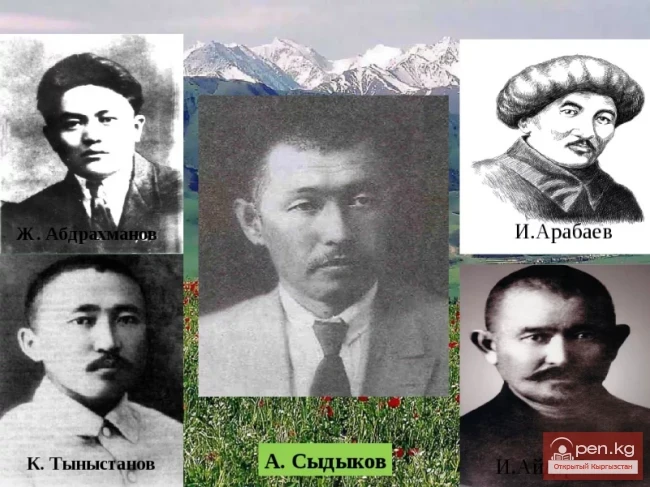

On the other hand, take Russia, which had numerous scientific schools and directions, and outstanding titans of historical thought such as Tatishchev, Karamzin, Kostomarov, Solovyov, Klyuchevsky, and many others. Thanks to their scientific search and contribution, Russian history received a multifaceted and diverse reflection and sound. Kyrgyzstan was not destined to go through this path, as it was impossible under the specific conditions of tribal organization. However, this does not mean that the Kyrgyz did not have their own historians. They were known as "sanjyrachis" and mainly engaged in describing genealogical history, the history of Kyrgyz clans. One of them was Osmonaly Sydykov, who has not yet been sufficiently appreciated by Kyrgyz historiography, the author of the first two published books on the history of Kyrgyzstan (1913-1914).

It was only during the Soviet era that history began to be studied professionally in Kyrgyzstan. But before it could establish itself as a scientific discipline, it immediately fell into the captivity of dogmatized Marxism and the only method recognized by it, the formation method. This method and methodology became foundational and continue to dominate even today, albeit no longer in its previous dogmatized form. The formation method has not yet fully exhausted its resources, especially in addressing scientific tasks that cover long time frames. However, when applied to short time periods, this method often fails and presents a distorted picture of reality, which is why it is time for historical science to master new and previously existing methodologies and scientific methods that have not been utilized in practice, in order to look at the historical past of the people in a non-traditional way, to find explanations for its socio-psychological features and motives of behavior, which Marxism did not allow.

In 1917, the Bolsheviks conquered and then destroyed the old world, but along with it, they buried the old culture. From that time on, the life of the Kyrgyz entered a "period when they no longer lived, but began to imitate life, and moreover, a life that was alien and incomprehensible to them." Imitation over time became widespread and continues to this day. This life began to be explained using European concepts and standards, unaware that applying foreign measures of philosophical thought could lead to a distorted meaning. As a result, the Kyrgyz people received not the history that should have been, but the one that was needed by the party ideologists. Consequently, reality was adjusted to fit the theory of the transition from feudalism to socialism, bypassing capitalism. Thanks to this falsification of reality, Kyrgyzstan at the beginning of the 20th century appeared as a political arena of fierce socio-class battles between the forces of progress and reaction.

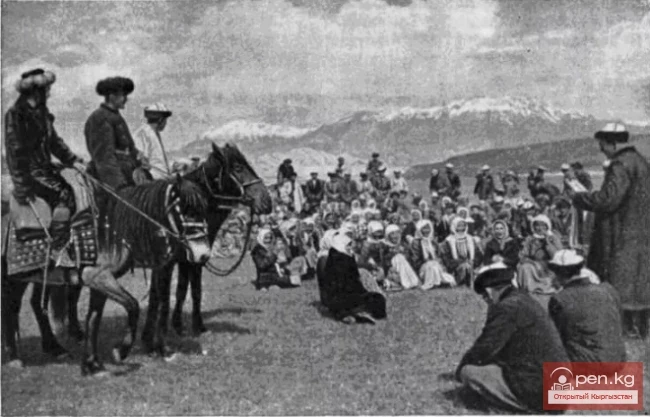

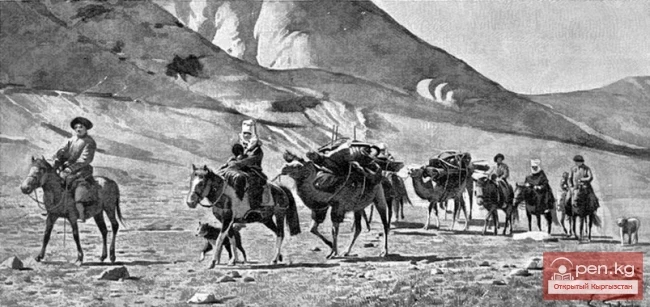

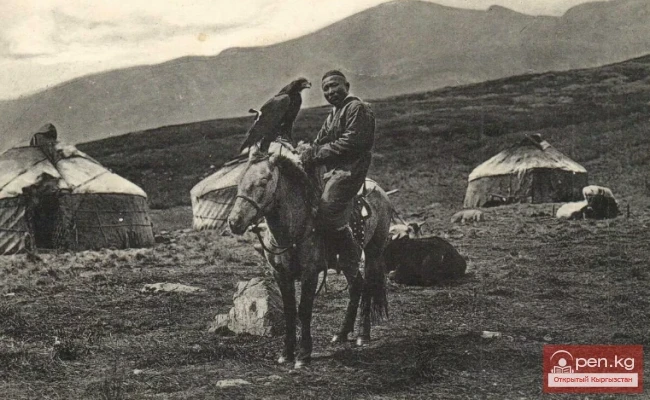

At the same time, it was absolutely ignored that by nature, a nomad is not aimed at and is not inclined to change, that ideas that could destroy his external and internal world provoke a sharp protest in him, and that essentially he is not so much a revolutionary, innovator, or reformer, but rather a guardian and protector of the existing order and foundations established in tribal society. The nomad was initially a collective being, which did not allow him to think or exist apart from his clan. Such are the roots or ontological premises of the tribal way of life. Therefore, any struggle in Kyrgyz society could not but bear the imprint of clan struggles, which explains the current revival of the phenomenon of tribalism, used during parliamentary elections, in personnel policy, in the movement of capital and material resources, distribution of goods, etc.

The 20th century was a time of forced transition of the Kyrgyz from a tribal way of life to the so-called Soviet system. Today, this time is referred to as the period of formation and strengthening of the command-administrative system, the era of totalitarianism or authoritarianism, but in our post-Soviet society, the tradition of a distorting approach has not yet been broken, and the foundations of a new approach have not been laid, one that would analyze the historical era based on the cultural values of the Kyrgyz people, their consciousness, psyche, philosophy, and customs, which are unique and invaluable for understanding Kyrgyz history. In Soviet historiography, this period was highlighted as a time of fundamental transformations in society and mass heroism of Soviet people in building socialism, and during the perestroika period, as a time of gross distortions, falsifications, deformations, transformations, and crimes of the Bolshevik system. It is difficult not to agree with such an assessment of historical past if one analyzes the past from the perspective of the Marxist method, which remains predominant in the study of historical thought to this day. Let us reiterate that only the outdated and most odious categories of this methodology have been discarded, while the doctrine itself has transformed into the ideology of social democracy, liberalism, or the doctrine of the priority of universal human values over class ones. Nevertheless, even these doctrines, despite their global recognition, do not fully take into account national moments, morals, and traditions that do not contradict universal human values, but at the same time exist almost autonomously and also have unique methodological value in understanding national reality.

Only now has our society come close to understanding how much the use of criteria and categories that are not inherent to Kyrgyz society can distort national history. This history has been so tangled and distorted that it is difficult for a modern person with their current worldview to return to the roots of the historical process, to explain its twists, regularities, and coincidences. The focus on the priority of universal human values somewhat helps to eliminate existing misunderstandings and false conclusions, but it does not eliminate the possibility of again going down the wrong path. Take, for example, today's attempts to find in the political figures of Kyrgyzstan in the 1920s their own "theorists" and reformers in the likeness of Lenin, Stalin, Trotsky, Bukharin, etc.

This is a vivid example of imitation. Such "searches" are conditioned by the fact that the Kyrgyz of the late 20th century stand on a different level of historical consciousness than their distant ancestors, and therefore it is impossible to evaluate their capabilities, ideals, and actions without delving into the essence of their historical consciousness, without standing on the same level with them.

Now, no one doubts that during historical development, law and morality, political institutions and structures, scientific representations, and the content of public consciousness change, and over time, human consciousness also changes, but not in terms of its content, but in terms of the structure and nature of higher mental processes such as perception, memory, active attention, thinking, imagination, volitional action, etc. This is emphasized because, when studying the past, historians generally proceed from the conviction that human consciousness has an ahistorical character and is not subject to influence. This is not a trivial question, as its resolution significantly affects historians' approach to past events. No one, perhaps, would deny that a person's social behavior, whether a tribal leader, scientist, politician, worker, or entrepreneur, is largely determined by how he perceives the world, thinks, feels, imagines, and analyzes.

If a researcher believes that the mental makeup of people does not change, he makes a serious miscalculation, as he inadvertently endows people of the past with the worldview of modern individuals, and subsequently attributes to them motives of behavior and attitudes that are not inherent to them. As a result, the genuine subjective reasons for the actions of our ancestors are misunderstood or distorted, and the actions themselves often acquire a different meaning in the historian's narrative than they actually had.

Kyrgyzstan in the 1920s. Introduction. Part - 4