Personality and History

Soviet scientific literature has always shown interest in the problem of the individual; however, it has not examined it thoroughly and deeply enough. The analysis of several of its aspects has been under an unspoken taboo. For example, issues of cannibalism, sexual attraction, or the significance of sexual selection in human origins, among others. Undoubtedly, other interests play a leading role in the spiritual life of a person, but this does not mean that the true nature of a person in science should be created with distortions. Should a work dedicated to the study of the history of opposition, the lives and activities of its leaders, consider the fundamental theme of the place and role of the individual in the historical process? The greatest historian of the 20th century, A. Toynbee, asserted that it should, for "to understand the part, we must first focus on the whole...". Practice shows that the previously widely used methods of analyzing this problem have already exhausted themselves or are exhausting themselves, and a new stage of knowledge is emerging.

Marxism, developed and supplemented by Plekhanov, Kautsky, Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and others, created an outwardly convincing picture of successive socio-economic formations. This theory recognized the people as the main creators, while individual personalities, primarily political figures, could only accelerate or restrain the historical process. This axiom stemmed from the fundamental position that a person is a sum and product of social relations.

Over time, this explanatory power of Marxism has been shaken by the pressure of facts, as its apologists long behaved as if this theory had been entrusted to them for eternal safekeeping—the teachings of the founders of scientific communism were canonized and quickly began to age. Meanwhile, global philosophical thought continued to advance. There was a reorientation of the object to the subject. It became clear that without studying the individual, there is no philosophy, and attempts to substitute it with the search for abstract laws of social development have failed.

It was inexcusable to ignore the fact that the laws of social development exist, but they only begin to act because there is a person. Those ideological systems that operated with the concepts of classes, nations, and masses have suffered defeat and collapsed. This indicates that the humanities must find the individual as a new reference point and not exaggerate the significance of the production process in his life.

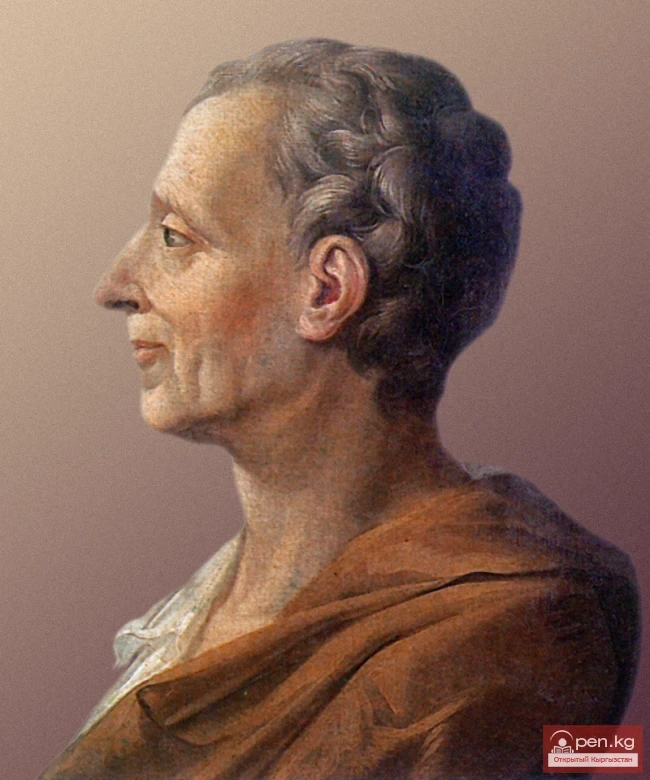

The emergence of numerous works exploring historical personalities vividly demonstrates that the Marxist understanding of history, which relied on the following positions, is fading into the past. These are: 1) historical necessity as an expression of the objective laws of humanity's development; 2) the determining role of being in relation to consciousness; 3) material responsibility as the main political and economic category of the historical process. In global science, the very relationships that have become familiar to us have changed. It has become clear that the necessary is a part of the accidental, and the role of the individual, the personality in history is much higher than previously thought. Accordingly, teachings such as personalism, general semantics, existentialism, or the philosophy of existence have come to the forefront.

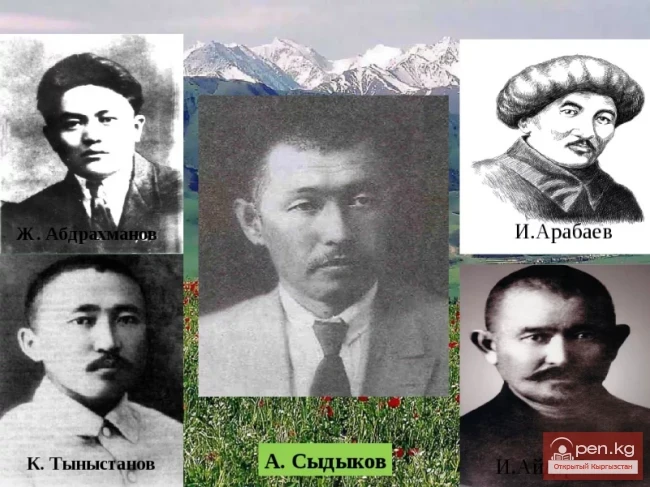

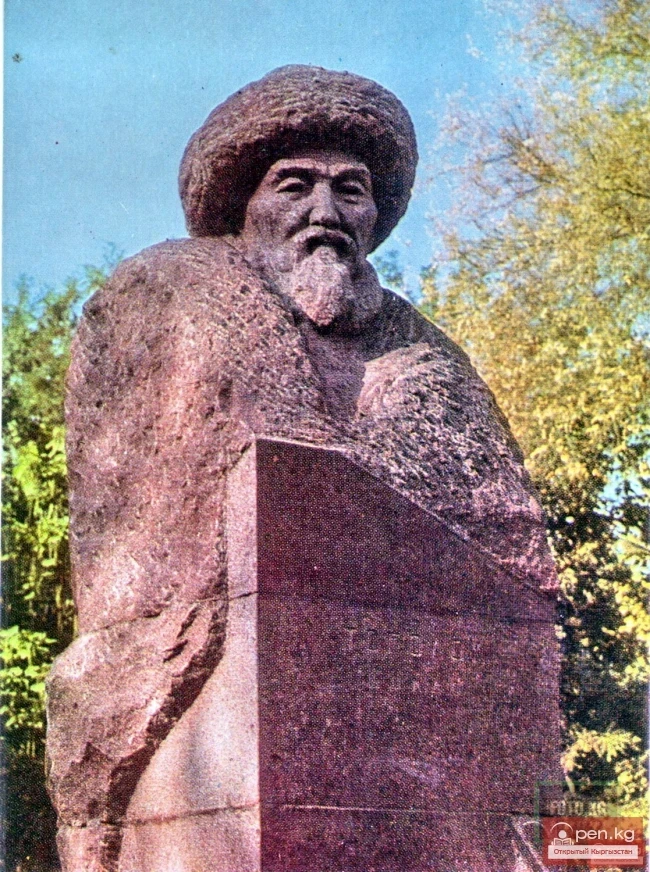

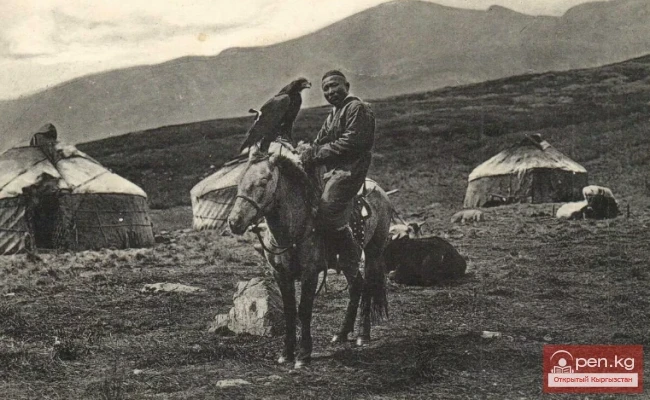

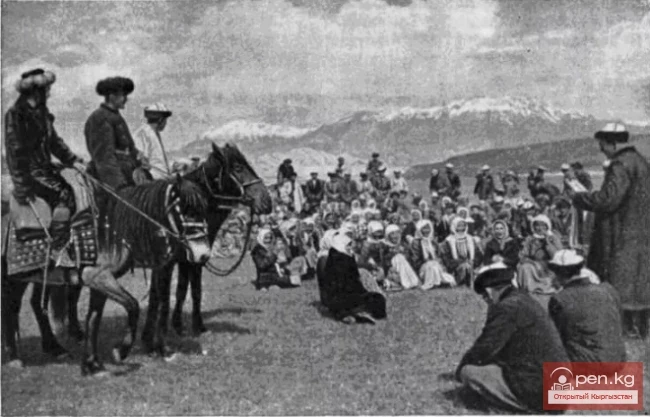

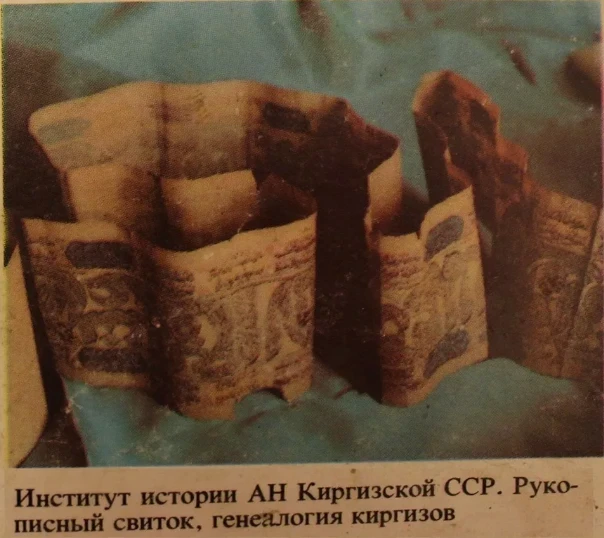

It should be noted that in the shadow of the objective laws of development, the first, if not the main, feature of human existence—its uniqueness—has been overlooked. "From the history of science," wrote A. Vernadsky, "we know many examples where only after several generations was what was once discovered but not published by an outstanding individual found again. It is quite possible and conceivable that much has remained completely undiscovered due to the untimely demise of those whose thoughts could have achieved this." Here, an important question is raised: What is more significant—the internal logic of the development of events or the intentions and actions of historical personalities? It is unequivocal that much in history has remained unfulfilled due to the premature death of those whose will could have realized it. Historians have much to ponder here. What, for example, is the role of the leaders of the Kyrgyz opposition of the 1920s, A. Sydykov, I. Arabayev, Yu. Abdrakhmanov, and others in the construction of national statehood, in the struggle against the totalitarian system? Could other people have resolved this issue differently?

The existence of each individual in specific manifestations is individual: his essence connects him with other people. Hence the conscious hostility of Marxism towards the individual and individuality, the proclamation of the primacy of social being over social consciousness. It is worth noting that the founders and theorists of Marxism were militant individualists. But this side of their activity has always been downplayed in apologetic biographies. They were portrayed as theorists and creators of revolutions, but the fate of these revolutions depended no less on those in power. There is no doubt that monarchists destroyed the monarchy, and communists destroyed the dictatorship of the CPSU.

The masses play a role in the revolutionary process, but not in the form that has become familiar to us. George Orwell, for example, divided the masses into three permanent groups: "The goals of these groups are completely incompatible. The goal of the upper group is to maintain their position, the goal of the middle group is to take the place of the upper group, and the goal of the lower group (when they have a goal, as they are usually burdened by everyday concerns, which they only think about—is to eliminate all differences and build a society where everyone is equal)." In this regard, the question arises: what is the foundation of society if the goals of the groups are incompatible? For a long time, based on Marxism, this foundation was mistakenly considered to be the economy, not the individual, for within the individual lies both the nature of society and the specifics of the historical process. But here it is also important to understand not what a person is, but what this person means. This is the significance of personality for history.

Knowledge of the peculiarities of the psychology of the Kyrgyz people