Moral and Ethical Norms of the Kyrgyz

From the perspective of a modern person, it seems not difficult to imagine the social structure of Kyrgyzstan at the beginning of the 20th century, to distinguish between exploiters and the exploited, and to discover the close connection between the manaps and bai with tsarism, Russian landowners, and the bourgeoisie. We have been trained for too long and too persistently to think within the framework of class struggle that we have completely forgotten how to view the ongoing processes and phenomena differently.

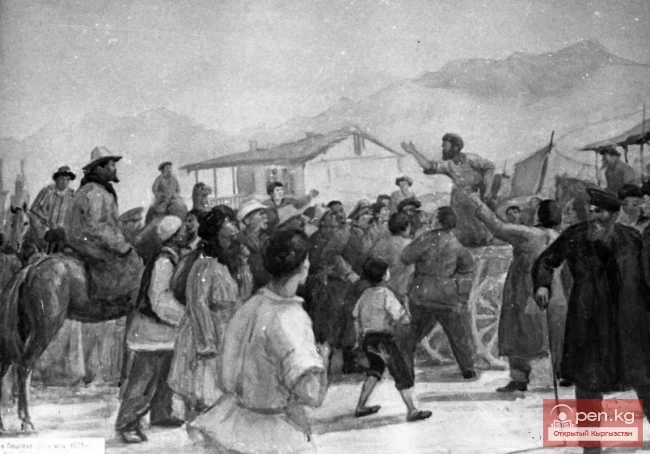

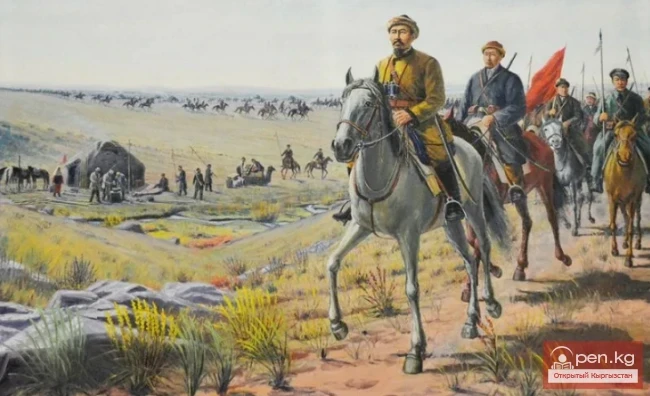

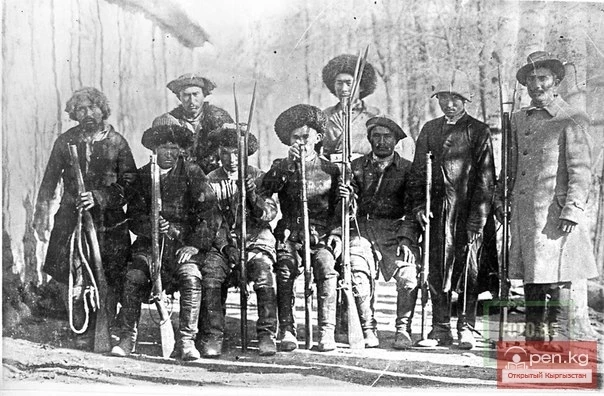

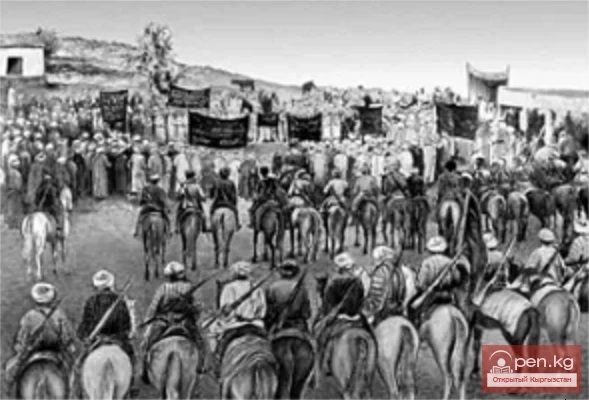

Therefore, numerous absurdities were invented, such as the hegemony of the working class and Kyrgyz peasantry during the uprising of 1916, which never actually existed and could not exist. There were only speculations, fabrications, and myths that served the prevailing ideology and were far from reality.

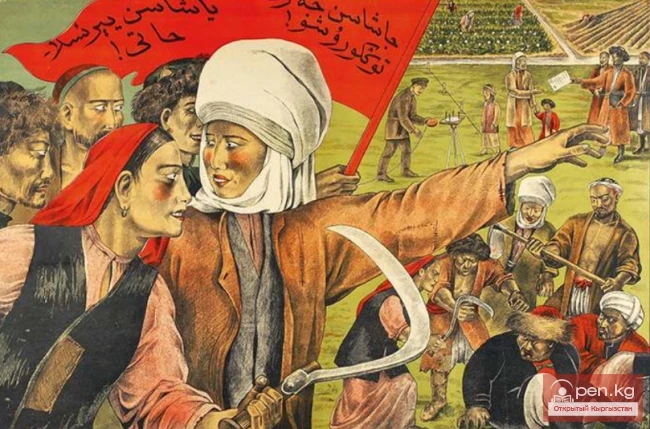

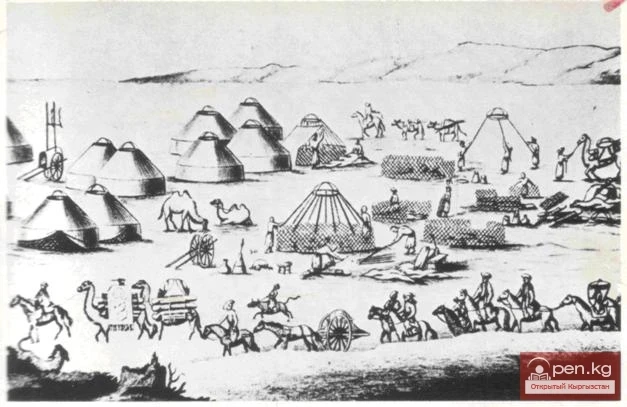

Meanwhile, the traditional consciousness of the Kyrgyz people indicates that they were not ready for a socialist revolution; they could only be "dragged" into it through violence, which is essentially what happened. The nomadic society itself, or rather its members, had absolutely no access to all these abstractions about class struggle, exploitation, the dictatorship of the proletariat, proletarian internationalism, and other tenets of Marxist theory.

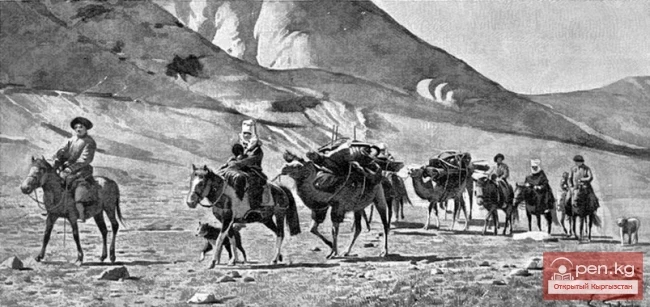

Nomads could not ponder which political concept was better and closer, or think about the necessity of changing the state and political structure of society. All these issues were alien and incomprehensible to the majority of Kyrgyz nomads.

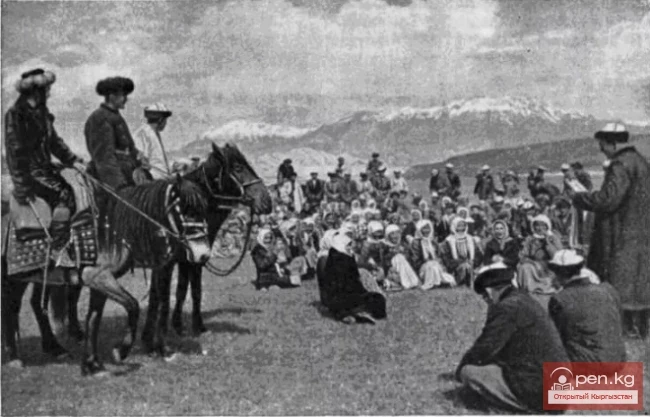

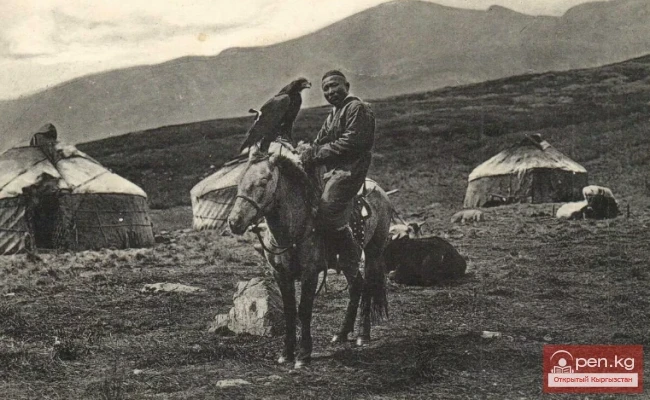

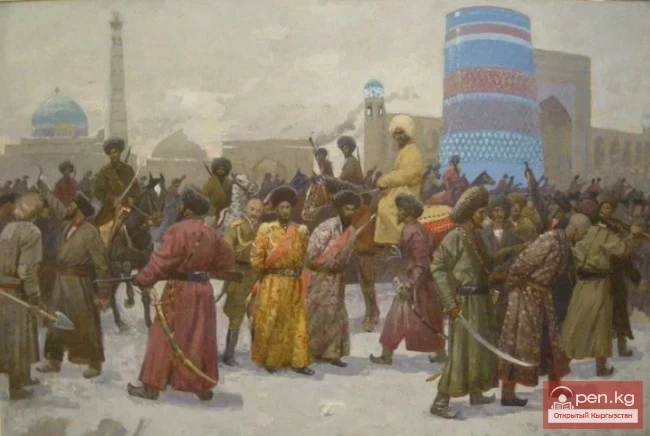

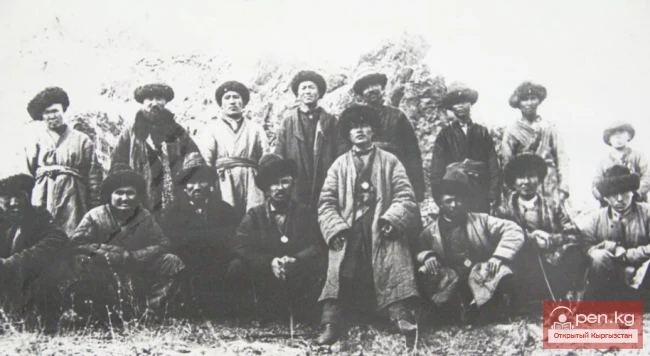

Who was the antithesis in the consciousness of nomads — the bai, manap, biy, or mullah? Of course not, because in their consciousness, the scheme of estate-class division did not form. In their view, "they" were representatives of other clans, neighboring peoples, settlers, and tsarist officials; "we" were their own kin, their own manap, their own mullah. The community among Kyrgyz clans, when they ceased to divide into "us" and "them," manifested only in religious beliefs and in the struggle against an external enemy. This is one of the reasons why, during the period of clan structure, Kyrgyz clans and tribes could not create a unified centralized state, as the traditional consciousness could not transform the categories of "us" and "them" into a single category of "us," i.e., place national interests above the interests of clans and tribes.

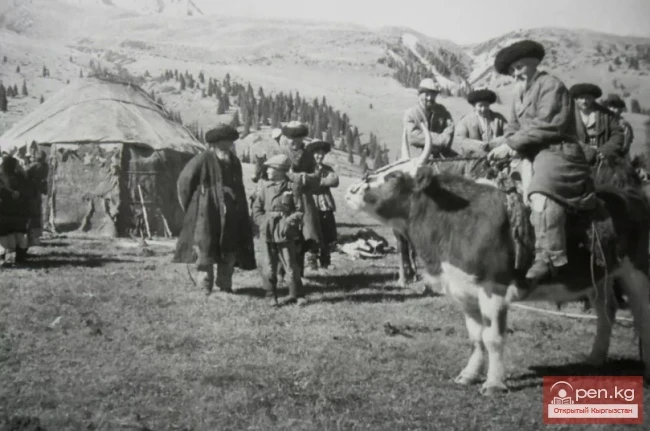

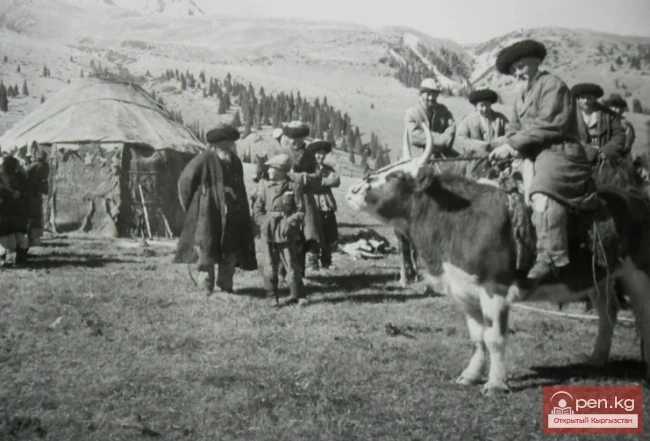

The lack of self-awareness in the individual and the need for sanction "from above" generated a certain social behavior among nomads, serving as a psychological basis for the subordination of children to parents, women to men, men to the clan, and the clan to the tribal leader — the manap. This explains the conformist behavior of nomads, based on tradition, norms, the so-called "kyrgyzchylik," which the Soviet power fought against throughout its existence. Literally, this term can be translated as "to be a true Kyrgyz." "Kyrgyzchylik" required nomads to adhere strictly to a number of moral and ethical norms, the violation of which would provoke public disdain. For example, the violation of "clan peace," "clan harmony." "Kyrgyzchylik" demanded that nomads follow the traditions and customs that had developed over centuries in relationships between clan leaders and clan members, between elders and juniors, women and men, parents and children, etc. "Deviant" behavior did occur in Kyrgyz clan society, but this "protest" usually did not arise from an awareness of one's position in the system of social relations or a desire to improve it, but as a result of personal grievances, violations of habitual relationships, and so on. Thus, individual protests in clan Kyrgyz society were directed not against clan orders or clan leaders, but against "abuse of power," "bad deeds," and so on. Moreover, these reasons were not consciously recognized, but only felt. A nomad, living in a clan society, could not independently develop an anti-clan ideology. It began to be actively created only with the coming to power of the Bolsheviks. But this did not happen immediately; the Kyrgyz needed a considerable amount of time to at least partially understand the specifics of this issue.

Features of the Group Consciousness of Kyrgyz Nomads