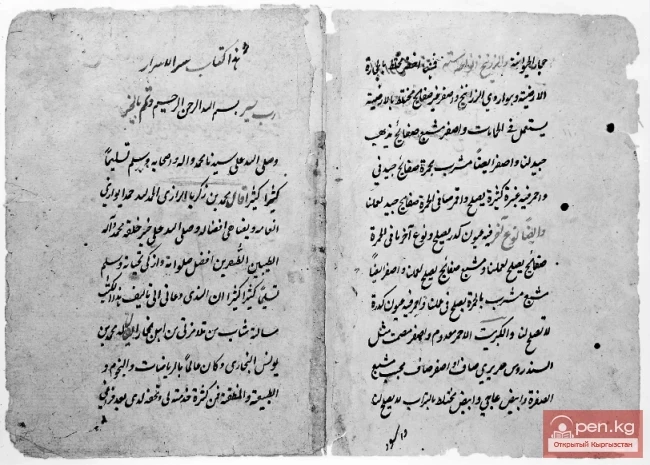

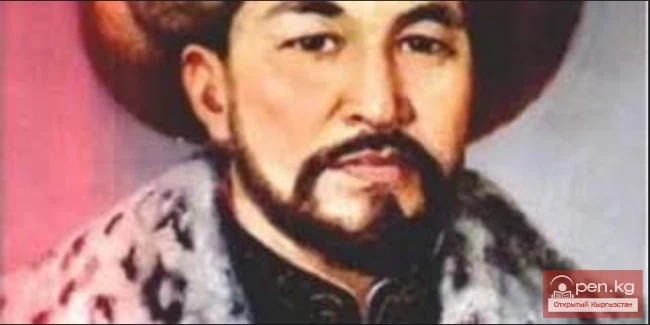

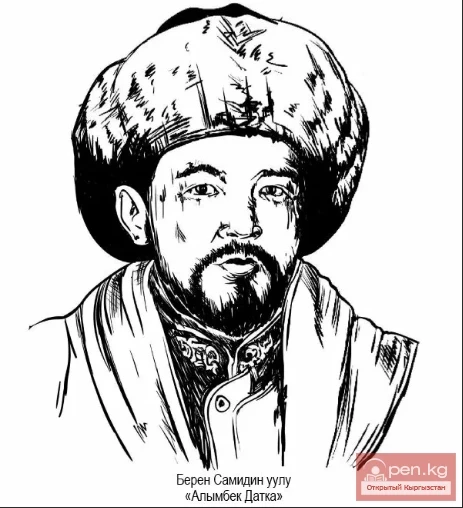

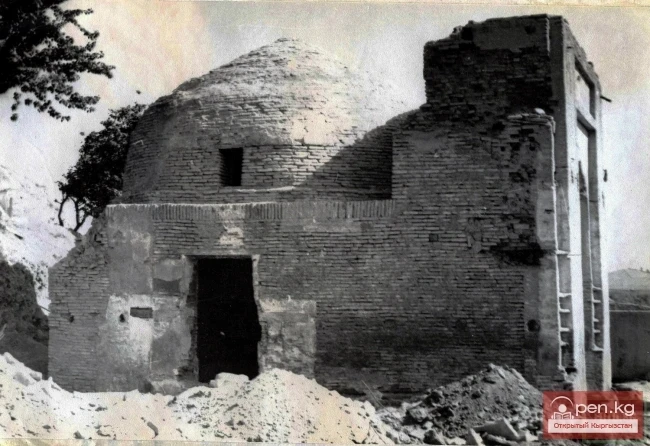

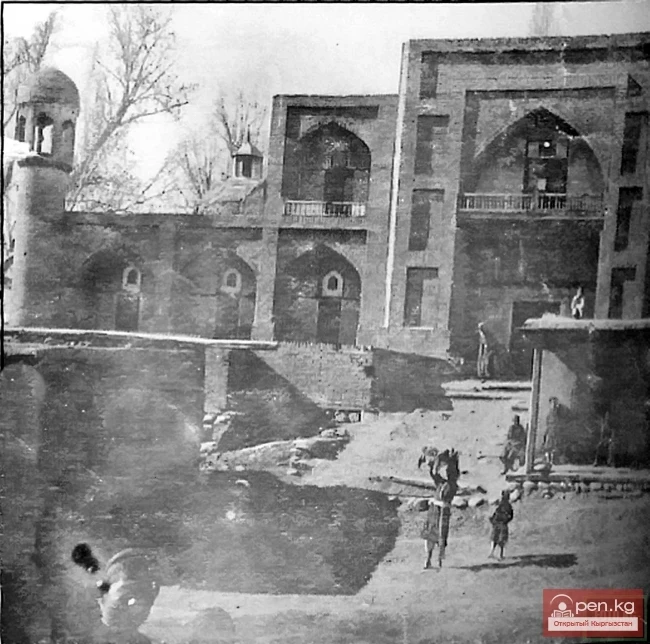

When examining the documents regarding the waqf of the Alymbek madrasa, it is hard not to agree that the founders of such property were not only sedentary agriculturalists but also nomadic feudal lords.

The representatives of the poor had a completely different attitude towards this form of land ownership. They viewed waqf as a tool of cruel exploitation. This traditional attitude was reflected in the preservation of certain rituals.

Thus, this sacred form of property, the right to which was considered inviolable and inalienable, gradually acquired a bad reputation. There was even a belief that any contact with someone else's waqf brings misfortune. Historian A. K. Pisarchik, who studied the history of the cities of Fergana, reports that in the old days, people avoided building their homes near mosques for fear that the wind might accidentally carry a leaf from a tree growing in the mosque's courtyard or pieces of plaster to them. This applied to any waqf land or waqf property. They were considered harmful, bringing misfortune to the house they entered, even if it was against the will and knowledge of the owner. In Bukhara, there was even a belief: to bring harm to another, one should scatter a little waqf land on the roof of the house of an undesirable person. Despite all this, the conversion to waqf was regarded as a pious act, fully supported by the clergy, secular feudal lords, and khans.

Waqf economy is a typical feudal form of land acquisition

According to historian D. Zainabitdinov, in southern Kyrgyzstan, waqfs were owned by the feudal lords Janibek and his brother Khalibek in Uzgen, and by Yusufbek-Kazy in Kurshab, as well as there were minor Kyrgyz waqfs in Alabuk, Laylak, and Batken. We have previously written about the Kyrgyz waqfs of the Kara-Bagysh village in the Andijan region, the Djigda-Mogol settlement near Suzak, the Bagish-Boston dacha, and the Kampyr-Rabat village near Jalal-Abad, among others.

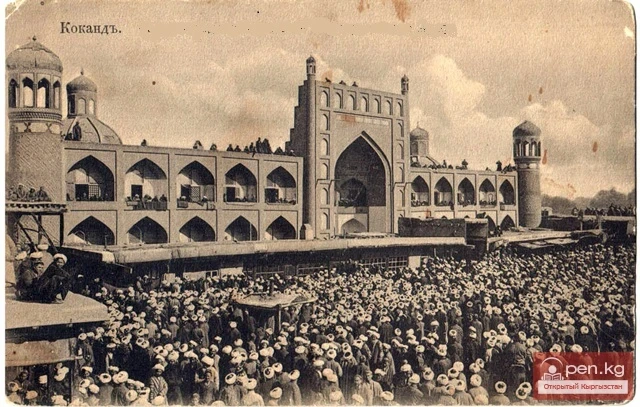

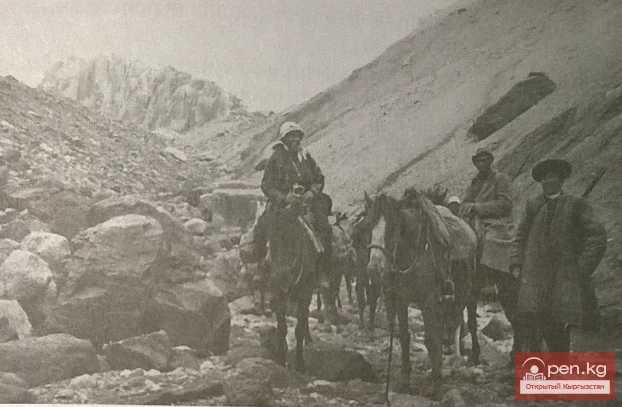

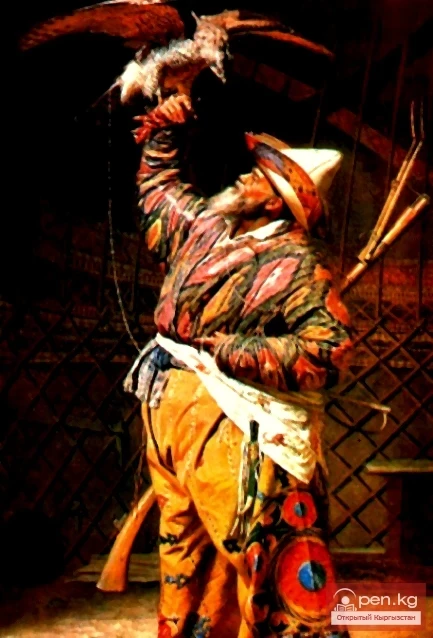

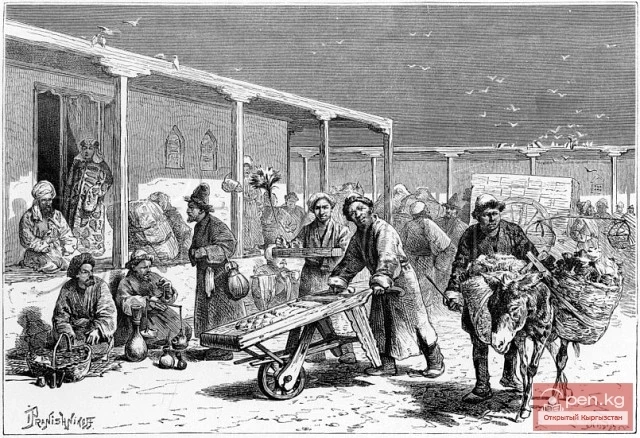

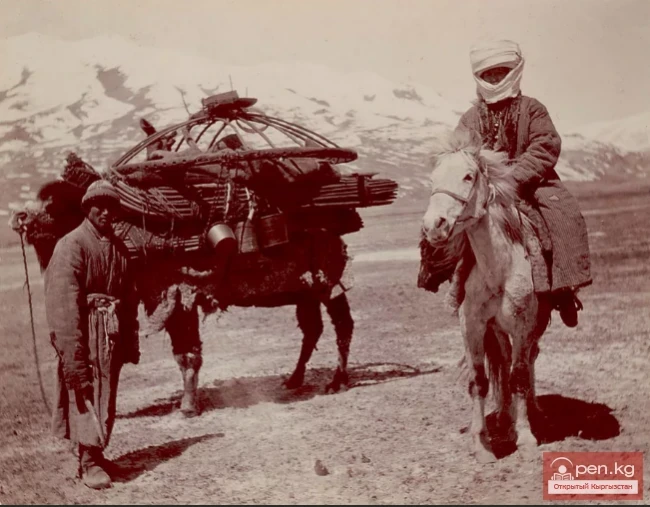

Of course, one should not overestimate the role of waqfs in the economic life of the country. Moreover, for example, in the territories of the nomadic northern Kyrgyz tribes, such forms of land ownership simply did not exist. However, it should be noted that they left their mark on agrarian relations among the Kyrgyz and contributed to the intensification of the exploitation of the working population. The spread of waqfs began only in the mid-19th century and is directly related to the history of the Kokand Khanate. The appeal of Kyrgyz feudal lords to this form of property was driven, on the one hand, by a desire to get closer to the Muslim clergy, which had significant influence among the khans and in court circles, and on the other hand, by a desire to have a guarantee of the inviolability of hereditary property, which was so unstable under the conditions of the eastern despotic regime of the Kokand khans.

The waqf economy was organized as a typically feudal system, based on rent and lease relationships with direct producers—dehkan farmers—and depending on the khan's permission, the power and influence of the feudal lord—the founder of the waqf—it could be fully or partially exempt from taxes or even subject to all types of taxes.

I would add that although the waqfs of the Kyrgyz did not represent an extensive institution or system of land ownership in the region, they were not a rare exception either. The emerging trends of integrating nomadic economies into agriculture, the beginning transition to sedentarism were accompanied by feudal lords turning to waqfs. This was a kind of testimony to their "commitment" to Islam and a protective measure against the overly greedy and relentless khan's tax collectors.

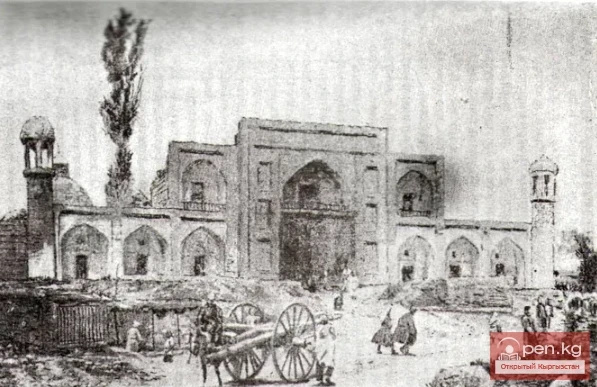

Using the example of the madrasa of the clan leader Alymbek, we examined one of the original forms of land ownership, which became a significant lever of influence for the Kokand rulers on the traditional way of life of Kyrgyz nomads, instilling in them the skills of agricultural management. Of course, waqf was far from being the only Kokand innovation in the life of the conquered people, as the reader will repeatedly see throughout the further narrative of our book.

Approval of agrarian legislation in Turkestan