Viability of Waqf Institutions

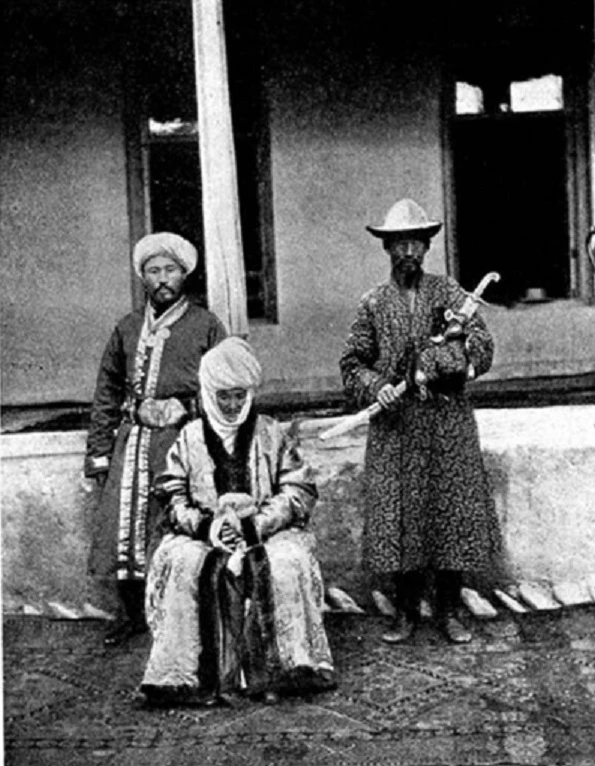

As the volost manager and mutawalli of the Alymbek Datka madrasa, Hasanbek had numerous opportunities for various abuses, which he did not hesitate to exploit. The villagers who cultivated the waqf land until 1898 (according to other sources, until 1894) paid rent to the waqf institution. As a result, by the end of the 19th century, even the biased imperial court initiated a legal case against the abuses of volost manager Hasanbek based on complaints from the residents, accusing him of illegally appropriating taxes, mishandling court cases, and other offenses.

The desire to increase profits drove Hasanbek, who by that time was already the volost manager and mutawalli, to build another mill near the Ishanchi canal in the Madin society of the Akburinsk volost.

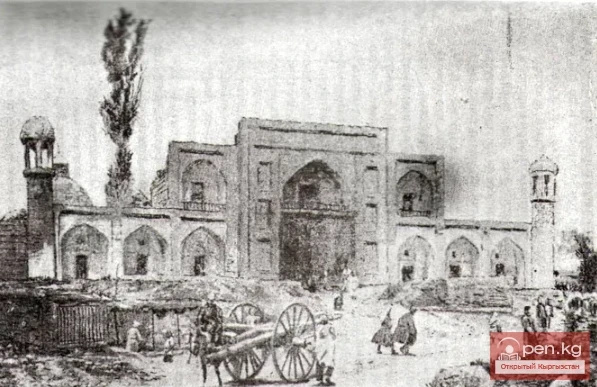

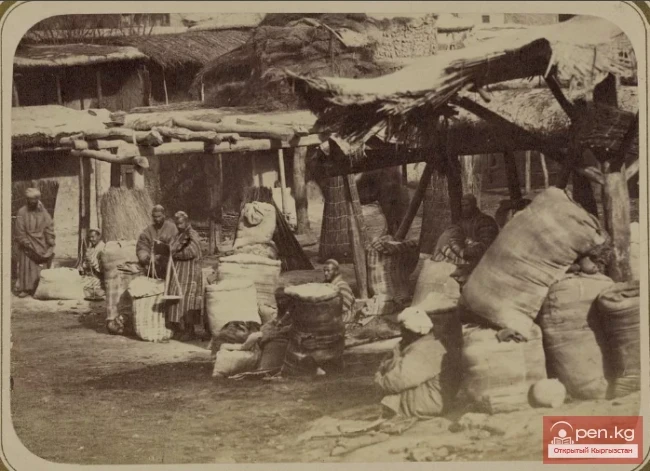

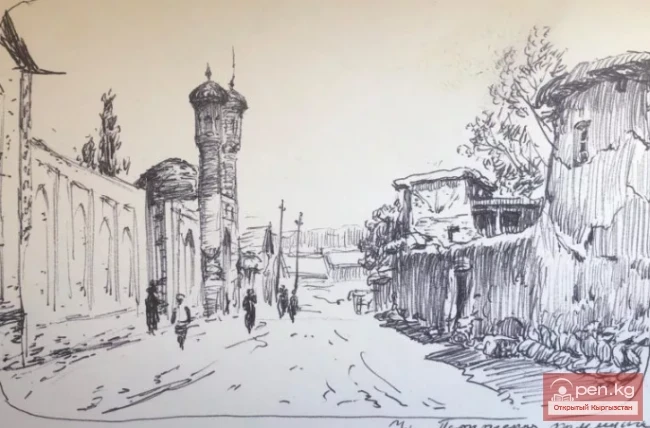

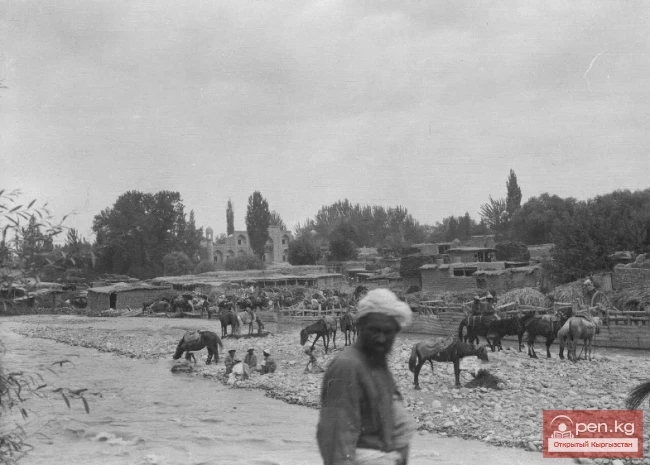

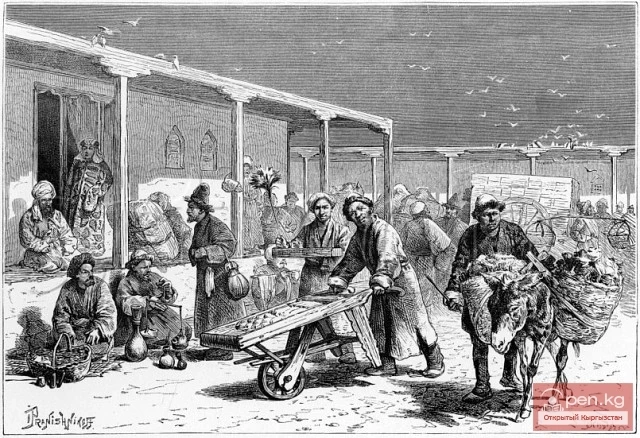

According to the chief of the Osh district, in 1886, Hasanbek owned 80 trading shops in the city alone, and according to data from 1906-1907, there were 120 trading shops and 30 tanaps of land associated with the Alymbek Datka madrasa (only the land directly uninhabited by peasants remained). Despite the fact that after the land tax assessments most of the land was transferred from the waqf institution to the state fund, the Osh madrasa of Alymbek continued to remain the wealthiest. In 1891-1892, an annual allocation of 160 rubles was designated for the maintenance of the mutawalli, while students in the senior classes received 20 rubles, those in the middle classes received 10 rubles, and those in the junior classes received 5 rubles.

The income from the trading shops was substantial for the madrasa, amounting to an annual profit of 1350 rubles, according to data from 1901.

The remaining waqf land was rocky and poorly irrigated, yielding only about 20 rubles in income. Indeed, due to their dilapidation, the shops were on the verge of complete destruction, but this hardly concerned the mutawalli: the main thing was that they still generated income. From the lands that were removed from the waqf during the land tax assessment and allocated for use by the population under the rights of obligatory tax articles, in the same year of 1901, a tax was calculated (but no longer in favor of the waqf institution, but in favor of the treasury) - for 1307 desyatins and 40 sazhen, it amounted to 3,139 rubles and 72 kopecks.

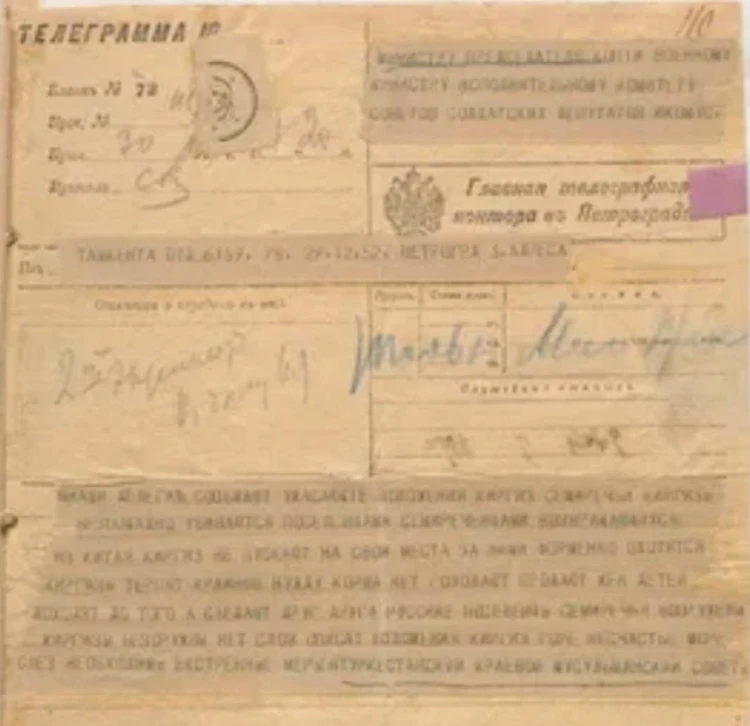

After the land tax assessment and the approval of agricultural legislation in Turkestan, all populated waqf lands used by the population were reclassified as state lands. The tax from them, even if it had previously gone to the waqf institution, was now redirected to the treasury, according to articles 255 and 299 of the Regulations on the Administration of the Turkestan Region from 1881. As a result, the overwhelming majority of waqfs were liquidated. Only uninhabited lands, directly and immediately used by waqf institutions and also confirmed by khan's certificates, remained. Consequently, the waqf of the Alymbek Datka madrasa was significantly curtailed. All populated lands of the Alymbek-chek village and other plots became state lands and were allocated for use to the population directly cultivating them, with the condition of paying taxes to the treasury, according to the decree of the provincial administration dated February 14, 1896. Nevertheless, the waqf of the Alymbek madrasa turned out to be quite resilient overall.

The remarkable resilience of waqf institutions is evidenced by an interesting fact. Even after the revolution, in the early years of Soviet power, the Alymbek Datka madrasa continued to retain only two plots of arable land and several trading shops in Osh until they were confiscated in the 1920s.

Preservation of the Waqf of Alymbek after the Fall of the Kokand Khanate