Agriculture. According to the legislative acts of the Russian Empire, the lands of the indigenous population were declared state property, which had significant political implications. From the very first days of governing the region, the Russian government effectively began to act as the supreme landowner. The 1886 statute legally defined land relations of the indigenous population of Turkestan, reflecting the essence of land policy in Kyrgyzstan. Although the land was generally declared state property, rights to private land ownership were still partially recognized. Milyk privileges (milyk - local privately owned land) were abolished, while waqf lands (waqf - a form of land ownership by Muslim clergy) continued to exist. The establishment of a new type of land ownership was also provided for. The settled population was allowed to buy and sell land according to local customs as well as Russian regulations (according to serfs). The right to acquire land was granted to individuals belonging to Russian subjects who practiced Christianity, as well as to the local population. The statute provided the nomadic population with land for hereditary use in three forms: winter pastures, summer pastures, and cultivated lands. Lands designated for nomadic grazing and cattle-driving routes were made available for the general use of the region's population.

In 1887, the regional government adopted the "Rules for Land Management in the Turkestan Region" and the "Instruction on the Rules for Land Tax Management in Settled Areas of Turkestan," which remained in effect until 1890. By January 1, 1910, the land reform in Turkestan, which lasted 24 years (20 years in the Fergana region), was considered complete. As for the nomadic districts of Kyrgyzstan, they remained untouched by the reform until 1917.

Commodity agriculture developed in Kyrgyzstan. The widespread development of "commercial" wheat crops became possible due to the close economic ties of commercial agriculture on the outskirts with the industrial development in the central regions of Russia. One of the main occupations of the indigenous population of Kyrgyzstan remained animal husbandry. In mountainous areas, especially in high-altitude regions, it was advantageous to engage in mobile animal husbandry, based on the use of natural fodder and associated with lower labor costs than a settled lifestyle. The Kyrgyz raised sheep, goats, horses, cattle, as well as yaks, camels, and donkeys. Kyrgyz animal husbandry was primarily extensive. However, many innovations (hay and feed harvesting for winter, combining pasture feeding with stall feeding, etc.), the beginning of the penetration of scientific veterinary medicine into Kyrgyzstan, and the establishment of veterinary medical points contributed to the development of intensive animal husbandry.

The socio-economic changes that occurred after Kyrgyzstan's annexation to Russia intensified the process of the Kyrgyz transitioning to a settled lifestyle. As a result, by the 1890s, settled settlements—kyshtaks—began to appear in southern Kyrgyzstan. On April 4, 1898, for the first time in the Chui Valley, 33 households of the Talkan rural district formed the settled village of Tash-Tyube. A new settled Kyrgyz rural district, Baytik, was established, which included two villages: Tash-Tyube and Chala-Kazaki in the Pishpek district. From 1910, land management began in the East Sokuluk Kyrgyz rural district of the Pishpek district. By January 1915, 10 settled Kyrgyz rural districts were officially formed, which included 67 villages with 8,267 households. In the Przhevalsk district, five Kyrgyz villages were established, which were classified as Russian rural districts. By the beginning of 1916, land management was completed in four more rural districts of the Pishpek district.

With the annexation of Kyrgyzstan to Russia, intensive socio-economic changes were observed in the region.

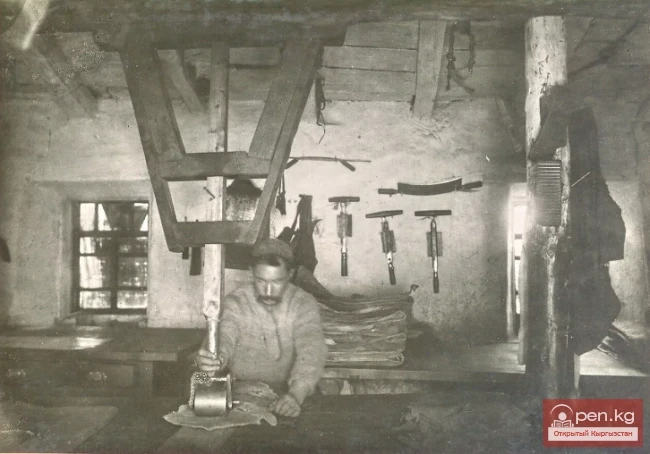

Thus, if before trade was barter-based, now there was a transition from barter, occasional forms of trade to fair-seasonal, and then to permanent trade. In Kyrgyzstan, measures were gradually implemented to stimulate local trade and crafts. Since 1879, urban and rural residents of the region were allowed to conduct duty-free itinerant trade in local handicrafts on market days. In the Fergana region, there was a zakyat trading system (zakyat - a certain trade fee from the merchant's revenue). However, in 1885 it was abolished, and the rules in effect in the empire were spread here. In 1889, a regulation on the state industrial tax was introduced, imposing an industrial tax on all traders, including nomadic ones. By the decision of the State Council on April 30, 1884, in Turkestan, including Kyrgyzstan, old forms and types of stamps, measures, and weights were replaced with new Russian ones over three to five years. "Kokans" and "tengas" (currency units that existed during the Kokand Khanate) were gradually withdrawn from circulation, and Russian currency was introduced.

With the encouraging policy of the Russian administration, progressive forms of trade—fairs and stationary trade—developed. The largest was the Auliye-Ata fair. Its turnover sometimes reached 4 million rubles. The Atbash fair also held significant importance, but with the opening of the Karkar fair (1893), the turnover of the Atbash fair began to decline. To improve the trading status of cities and attract more nomads to them, fairs were established in cities as well. Thus, Przhevalsk, Pishpek, and Tokmak city fairs were opened. In the early years, they were successful. Such fairs did not hinder the development of stationary trade; on the contrary, they gradually merged with it and turned into permanently operating "trading points." Stationary trade existed in the settled areas of Kyrgyzstan even before the region's annexation to Russia—in the form of bazaars. They were held weekly, but trading took place daily in the market square. In the early 1880s, the regulation of bazaar operations began in the cities of the Fergana region. By the early 20th century, the cities of Pishpek, Przhevalsk, Tokmak, Osh, Uzgen, and others became centers of trade. Many areas in southern Kyrgyzstan gravitated towards the trade and industrial centers of the Fergana region. Many villages, both in the south and the north, gained significant trade importance: in 1913-1914, there were about 3,000 trading shops in 36 populated points in Kyrgyzstan, excluding cities. In Pishpek, Przhevalsk, and Osh, there were 139, 171, and 1,300 trade and industrial establishments, respectively. Trading shops were also opened in mountain pastures.