Stories of Individual Traders and Other Russian People about Osh

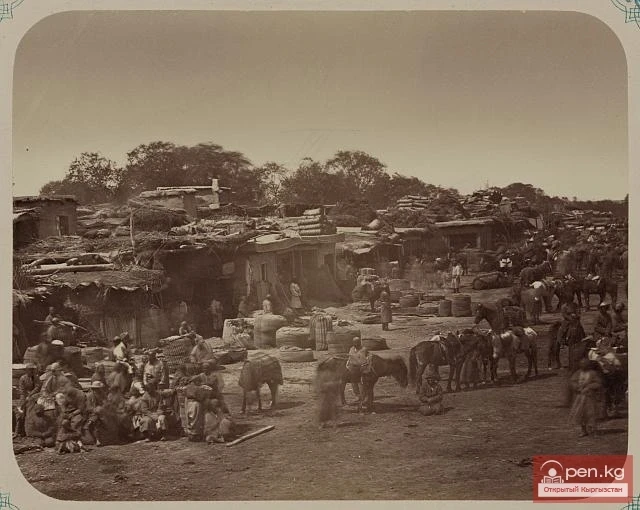

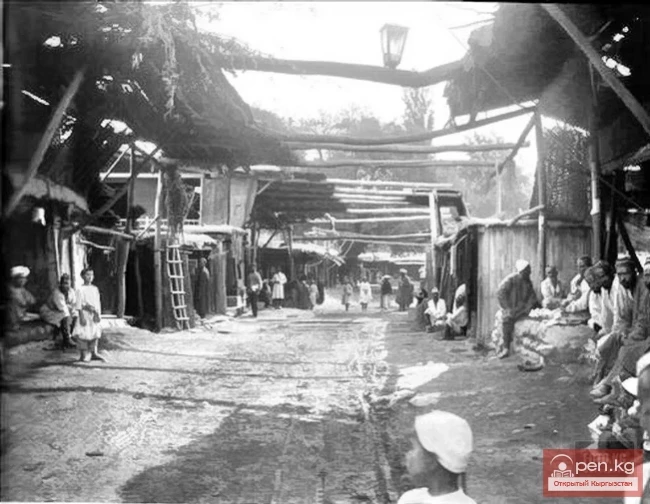

Documentary sources from the time of Kyrgyzstan's dependence on the feudal despotic Kokand Khanate, both Kokand and Russian, contain very few factual and reliable details for describing the city of Osh, as well as other settlements in Eastern Fergana. However, from the sparse accounts of individual traders and other Russian people — "involuntary travelers," like F. Efremov, notes sent to Kokand by representatives of the Russian authorities, domestic and foreign travelers, a general picture emerges about the state of the city of Osh in the first three-quarters of the 19th century. Some details become clearer: its approximate size, notable topographical features, the general character of construction, the occupations of the residents, certain urban events during the history of the khanate, etc.

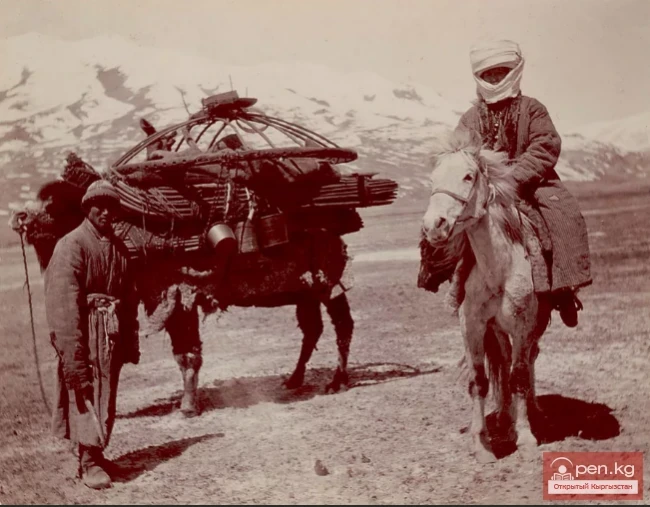

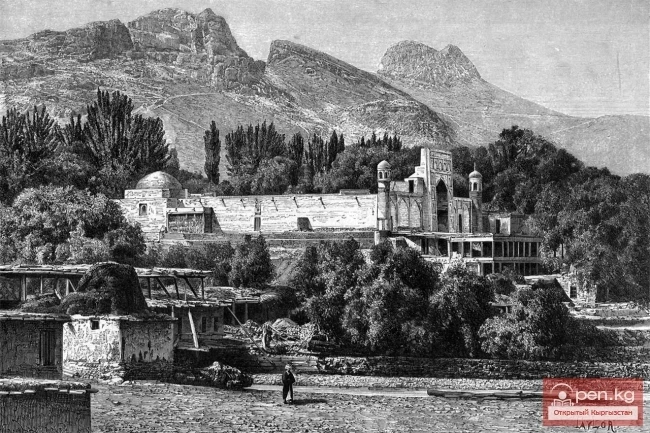

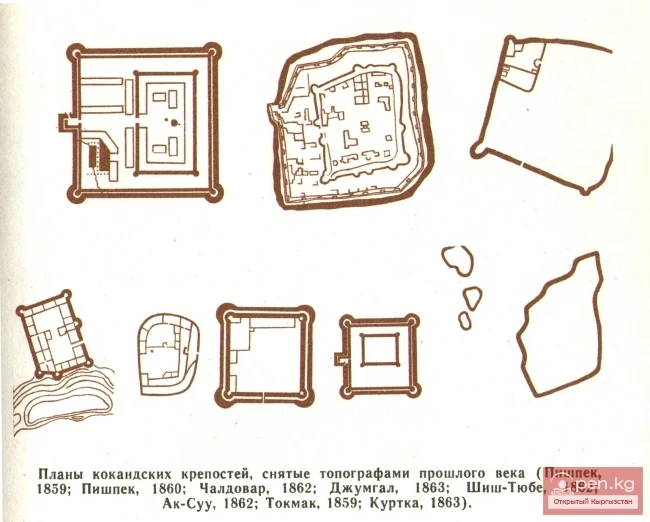

In the mid-18th century, Osh was more of a temporary encampment than a permanent dwelling for Kyrgyz nomadic feudal lords. Eastern sources directly state that the Kyrgyz "spend the winter in the city of Osh, ... engage in agriculture and graze livestock in summer pastures." At that time, the city was evidently not well fortified, and there were no defensive walls (sources, in any case, do not report them). However, archaeological surveys of the surroundings of the city suggest that, at least on its southwestern outskirts, facing the Alai — the most "restless" area of the Kokand Khanate, some fortress stood.

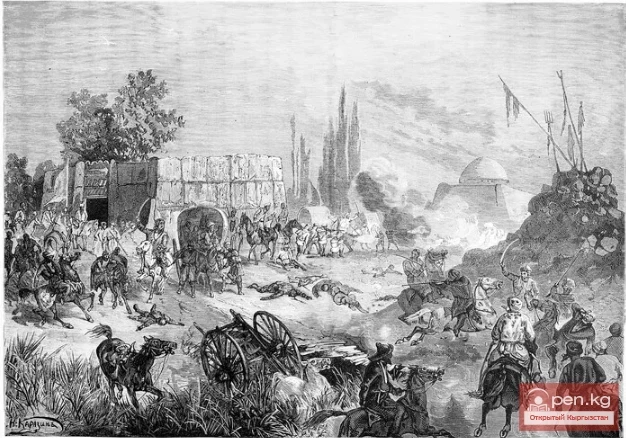

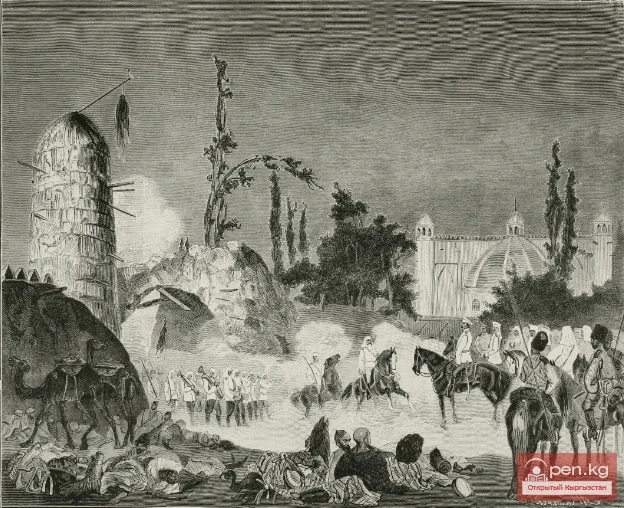

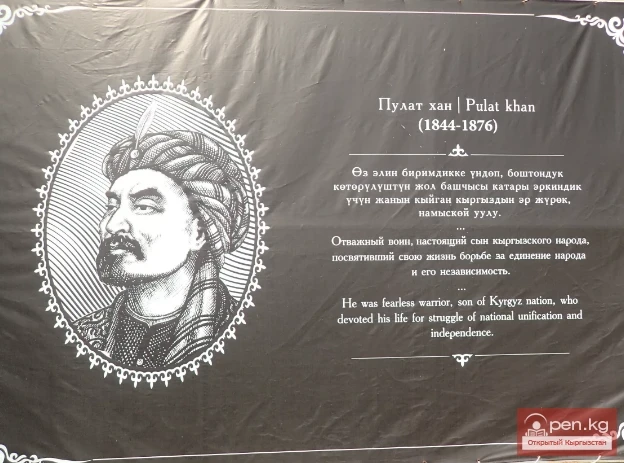

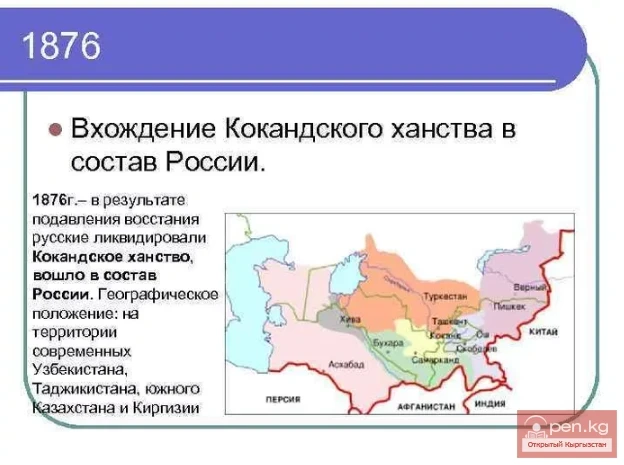

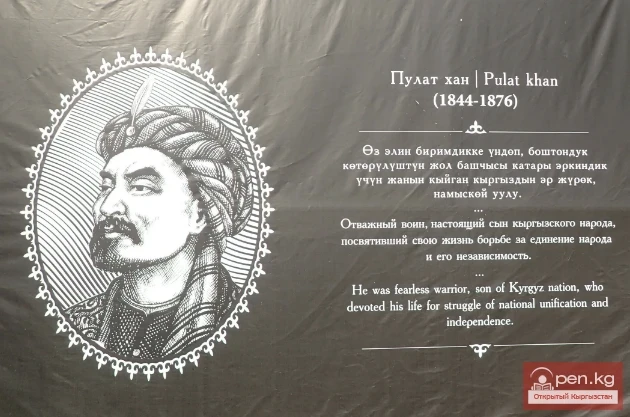

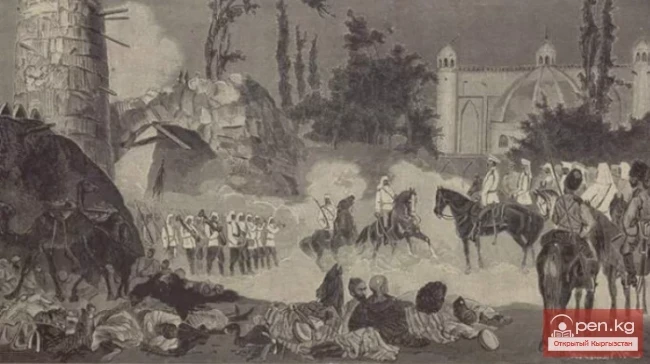

Narrative sources mention the fortress of Mady, located just one farsakh from Osh. In 1275 AH (1858/59), another fortress was built near Osh in the Langar area. These fortresses took the first blows from the rebels against the khan's oppression. Osh itself changed hands with struggle. The citadel, which was located in the center of the city, was not adapted for long-term defense; for example, when Kyrgyz rebels reached the village of Aravan in the 1870s and attacked the Osh citadel, the khan's governor immediately fled the city.

The first Russian traveler to visit Osh in the 1770s was the non-commissioned officer Philip Efremov. A "traveler by force," an escapee from captivity, he naturally pays special attention to the distance between cities. From Osh to Margilan, F. Efremov noted, it was a 3-day journey, and from Osh to Kashgar — 13 days. F. Efremov also notes the independence of the Kyrgyz from the Kokand Khanate, but the city itself, according to the author, was already "subject to him."

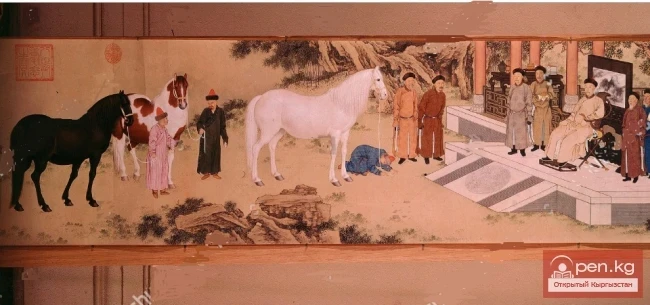

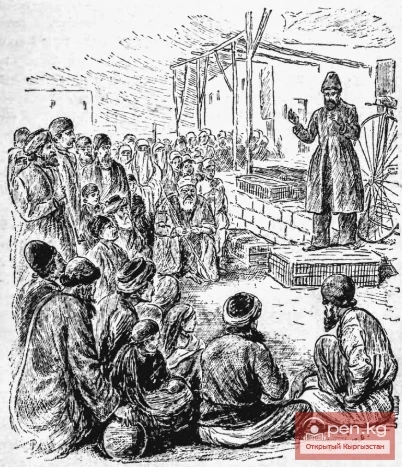

Siberian Cossack Maximov, who saw "Kyrgyz and Kipchaks grazing near Osh" on his way to Kashgar in the early 19th century, reported on the pilgrimage of Muslims to the shrine of Takht-i-Suleiman.

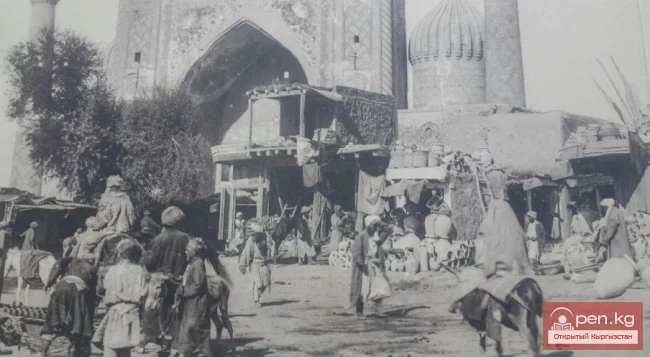

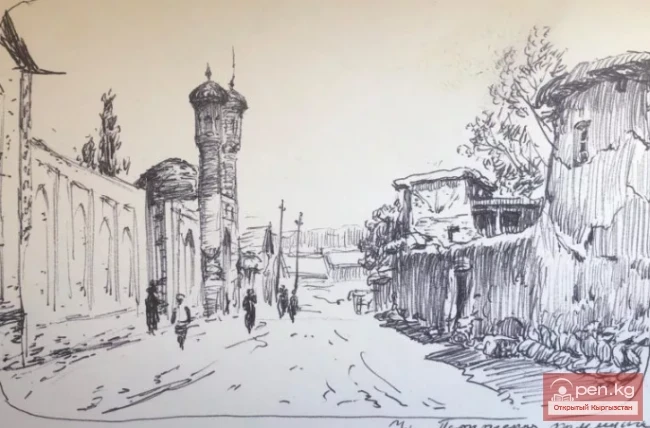

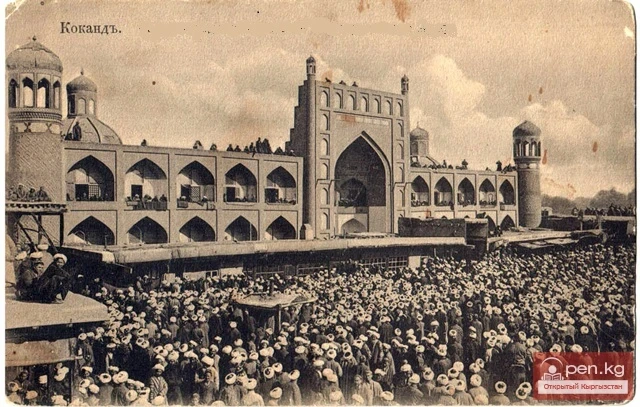

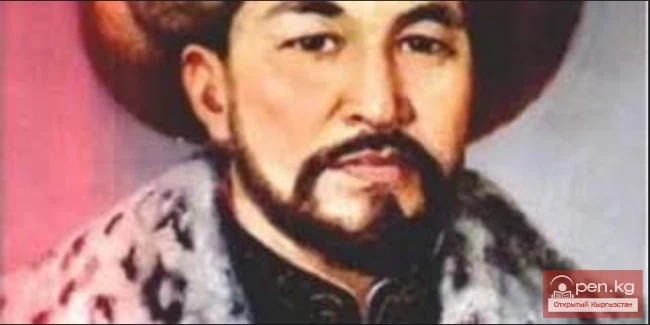

Kokand ambassadors who were in Turkey in 1832-1833 named 12 large cities, numerous towns, and villages as part of the Kokand Khanate. One of them was undoubtedly the city of Osh, which served as the administrative center of the vilayet. In narrative sources, Osh was sometimes also referred to as Takht-i-Suleiman — named after the mountain rising on the western outskirts of the city. The "holy" mountain attracted pilgrims from various Muslim countries, making the city known as one of the religious centers of Fergana. Here, from the late Middle Ages, ancient mosques have survived, Islam was further spread by the efforts of the Kokand clergy, and madrasas were built, dozens, if not hundreds, of mosques. One of the most famous was the madrasa of Alymbek (which we will discuss in more detail below). Pilgrimage heightened Muslim fanaticism. Medieval religious obscurantism did not contribute to social and cultural progress.