Multi-Step Politics of Kyrgyz Tribes in the Late 18th Century

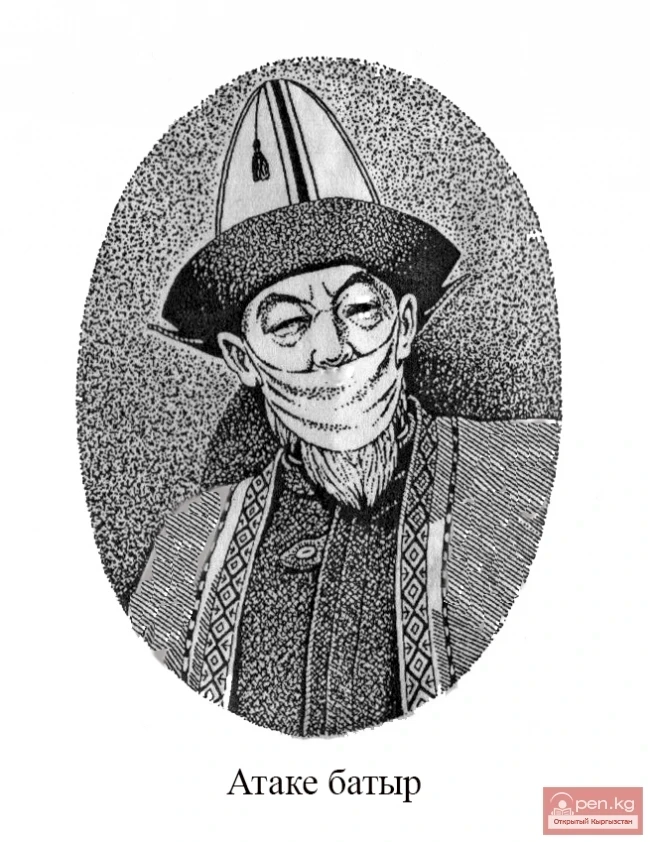

In the late 18th century, Kyrgyz biys Atake and Esengul, disheartened by internal conflicts with the Kazakhs, came to the conclusion that reconciliation was necessary. In 1786, deputies arrived from Kazakh Sultan Khan-Khodzha to the Kyrgyz to negotiate the terms of an agreement, who, while offering friendship, nevertheless... demanded amanats - noble hostages. As reported by the Omsk merchant Zakhar Penyevtov, who traded in Kazakh and Kyrgyz pastures, the Kyrgyz, not expressing a clear agreement or sharp rejection, tried to steer the discussion towards the necessity of an alliance between neighbors, "for as it is for you, so it is for us," they said, "the common enemies are the Chinese." An agreement was never reached. Moreover, some Kyrgyz feudal lords, pursuing a separatist policy, looked towards the Kokand Khanate for assistance. It was during this time that a split even occurred among the feudal lords of one tribe - the Sarybagysh. Bey Esengul had some disagreement with Bey Atake, and the latter was forced to move from the Chui Valley to Eastern Prissykul on the river Chaty (Shaty), a tributary of Tyup.

In turn, Esengul, who was oriented towards the Kokand Khanate, could not peacefully coexist with Bey Atake, who sent a delegation to St. Petersburg in 1784 requesting protection. Therefore, Atake preferred to migrate to the Bugyns, who were more interested in Russia than in Kokand. However, some individual Kyrgyz feudal lords showed persistent sympathy towards the Kokand Khan. The reasons for the Kyrgyz turning to the Kokandis were not only the disputes between Kyrgyz feudal lords and Kazakhs but also the desire to secure support from a more powerful neighboring khan against the ambitions of the Qing. According to legends, the manaps of the Sarybagysh clan sent their representatives led by Kuvat, son of Esengul, and Asan, from the Jantay clan, to the ruler of Kokand in 1791. They brought as a gift to Narbutabek 18 of the best racehorses.

This embassy, aimed at establishing closer contacts with the Kokand Khanate, did not intend to accept its vassalage. Torn by internal strife and constrained, on one hand, by the increasingly powerful Kokand possession and, on the other, by the Qing Empire, which had approached the very borders after the defeat of the Dzungar Khanate, and subjected to raids by Kazakh feudal lords, the Kyrgyz struggled to maintain their independence, gradually falling more under the influence of Kokand.

Thus, by the 1780s, the central Fergana Kyrgyz and the Kyrgyz of Tian Shan, who migrated beyond the Chirchik River, fell under the dependence of the Kokand Khanate. However, as seen from the notes of Philip Efremov, who passed through Fergana in the 1770s, even the southern, most likely predominantly foothill Fergana and Alai Kyrgyz behaved quite independently, showing no signs of their subordinate position in relation to the khanate. Kokand, the traveler writes, is only "adjacent" to their possessions. Narbuta, however, attempts to conquer neighboring Kyrgyz tribes that refuse to recognize Kokand's authority, but he does not always succeed. Mirza Kalandar, the author of the manuscript "Shahname" ("Tarikh-i Omar-khani"), reports on the failure of the Kokand commander Khan-Khodzha's military expedition to Ketmen-Tyube at the end of the 18th century: "And no matter how much the experienced men and warriors - the pillars of his state - deliberated, exchanging thoughts on how to set this rebellious people (the Kyrgyz of Ketmen-Tyube - Note by V.P.) on the right path, no way to conquer this mountainous area was discovered."

However, it cannot be said that the majority of the northern Kyrgyz tribes were subordinate to the relatively large Tashkent possession at this time. From the "explanation" of the Cossack ataman sub-lieutenant Telyatnikov about his trip to Tashkent in 1797 "for various tests and especially to learn about the abundance of gold and silver ore presented," it is evident that the Kyrgyz at that time were not dependent on Tashkent and freely migrated to the northwest of it. This is why the Siberian engineer I.G. Andreev, the first among authors in Russian literature to dedicate a special chapter to the description of the Kyrgyz at the end of the 18th century, writes in his autobiographical notes that at that time neither the Kokand ruler Narbuta nor the Tashkent Yusuf-Khodja had the northern Kyrgyz "under their protection."

According to I.G. Andreev, the Kyrgyz bordered the Kazakh zhuzes, Kokand, and China. The Kyrgyz, he writes, due to their freedom do not give anyone a respite, "organize into large parties, fiercely defend themselves." Nevertheless, there have been periods in history of temporary subjugation of individual northern Kyrgyz tribes by both Kokand khans and Tashkent rulers. However, this was an episodic phenomenon at the end of the 18th - beginning of the 19th century.

Politics in Eastern Turkestan in the Late 50s-60s of the 18th Century.