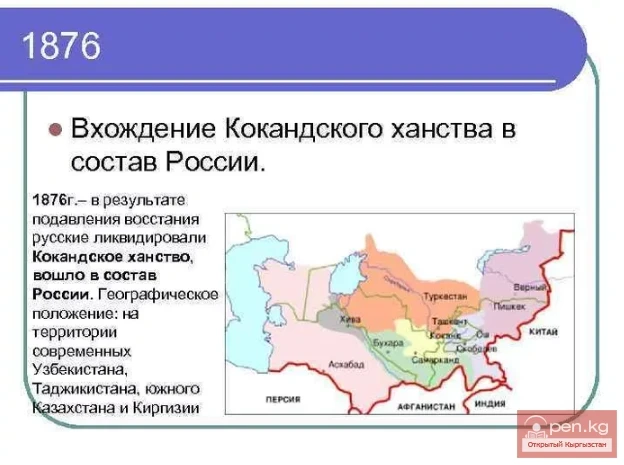

The Uprising of Ordinary Kazakhs and Kyrgyz Inhabitants of the Talas Valley Against the Dominance of the Kokand Khanate

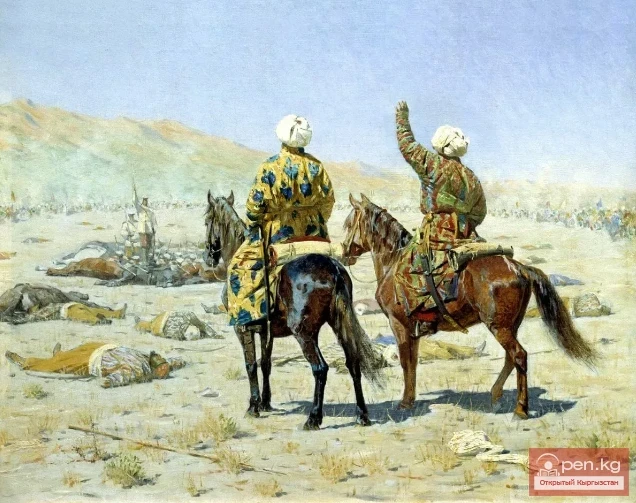

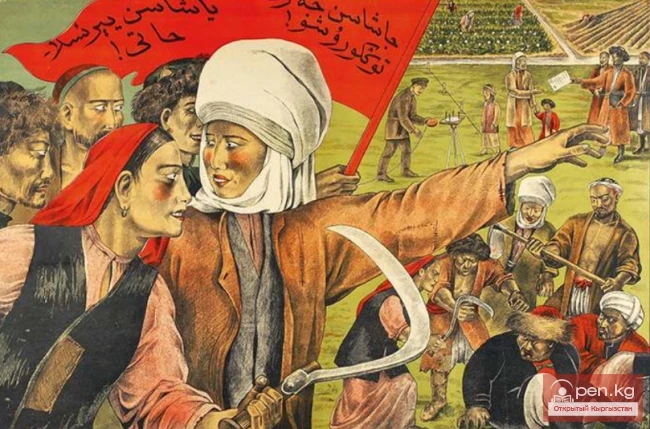

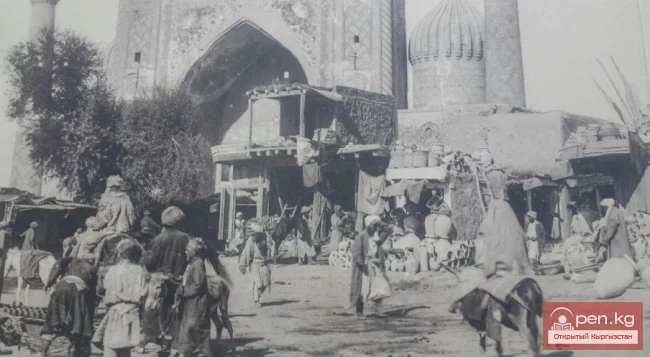

The increasing social and national oppression, the arbitrariness and violence of local feudal lords and Kokand exploiters, the powerless and humiliating position of the working people, devastating internecine conflicts, and bloody struggles for the khan's throne brought the masses to the brink of poverty and claimed thousands of lives. All of this overflowed the cup of popular patience and raised the working people to fight against their oppressors for the right to exist, for social and national independence.

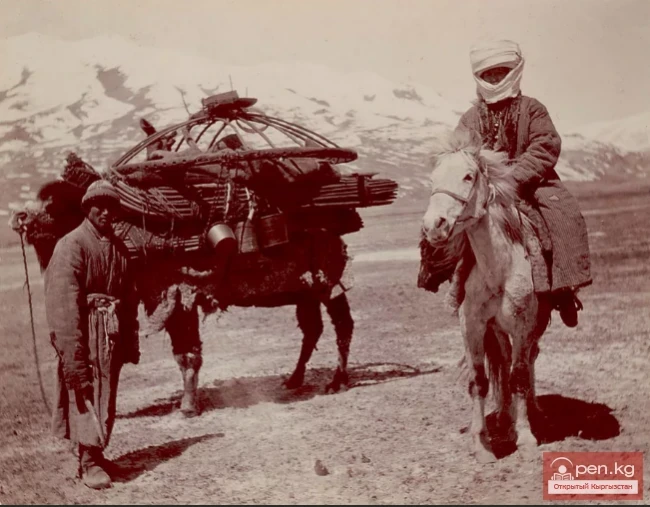

The commonality of the historical fate and social interests of the Kyrgyz, Uzbek, Tajik, and Kazakh working people, who were suffering under the unbearable oppression of the Kokand feudal lords led by the khan, contributed to their joint uprising against the despotic khan's authority. Despite the policies of the Kokand rulers and local feudal lords aimed at inciting national hostility between brotherly peoples, the working masses often united for a common struggle and stood shoulder to shoulder, hand in hand against the hated khans and officials. Often, ordinary Uzbeks, Tajiks, Kazakhs, and representatives of other Central Asian peoples joined the Kyrgyz working masses who rose up against the Kokand despots. In turn, Kyrgyz herders actively participated in the liberation struggles of other peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan.

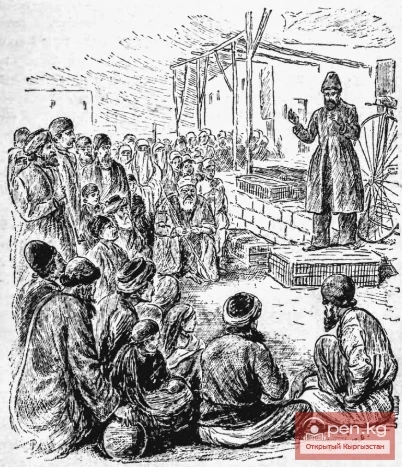

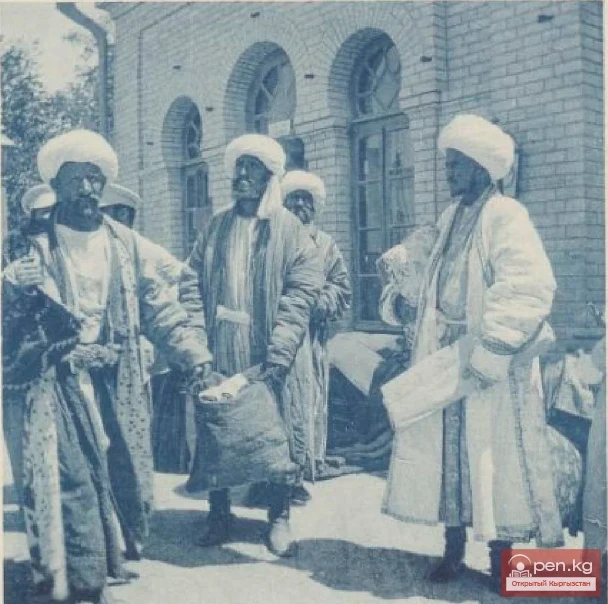

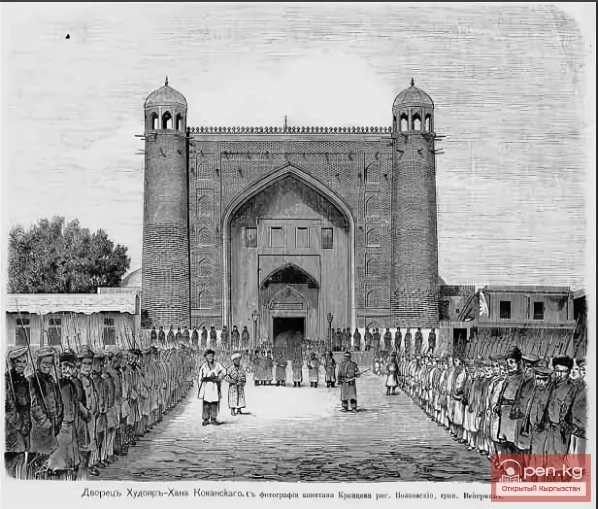

In short, the history of the Kokand Khanate was essentially a history of popular uprisings against feudal-khanist oppression and despotism, for social and national freedom. The outrage and indignation of the oppressed masses, often escalating into open uprisings, became a common occurrence. Even high-ranking tsarist officials, who patronized the power of Khudoyar Khan and the feudal lords surrounding him, could not deny this.

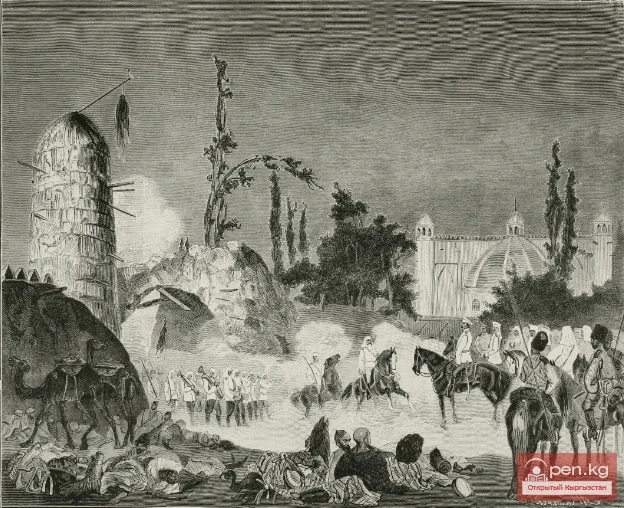

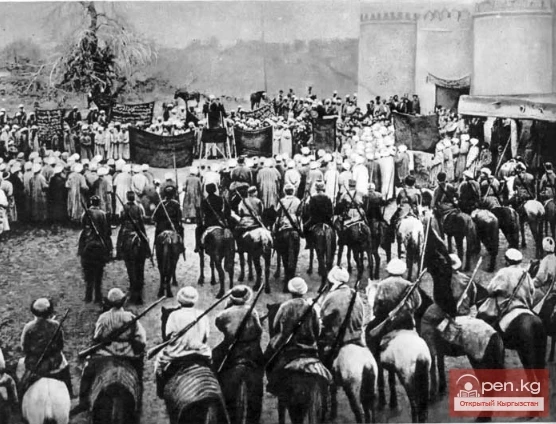

The brutal actions of the Kokand khan's troops, aimed at conquering neighboring regions and peoples, met with strong resistance from the indigenous population. The struggle of the working people against the feudal-khanist regime began immediately after the establishment of the Kokand Khanate's dominance. For instance, in 1809, the inhabitants of the surrounding areas of Tashkent did not reconcile with the regime established by Alim Khan. They rose up against the khan's governors in Tashkent. The uprising of the Uzbek farmers was joined by neighboring nomads—the Kazakhs, who were fighting against Kokand's dominance. The leader of the rebels was Kabil from the Karakalpak clan, belonging to the ruling dynasty in Tashkent. The main forces of the rebels were concentrated in the fortress of Bagodan, located in the mountains. They posed a serious threat to the khan's troops and the trade caravans passing through the fortress. For a significant period, the rebels troubled the khan's authorities. However, through deception, the Kokand khan and his appointees in Tashkent managed to suppress the uprising and kill Kabil.

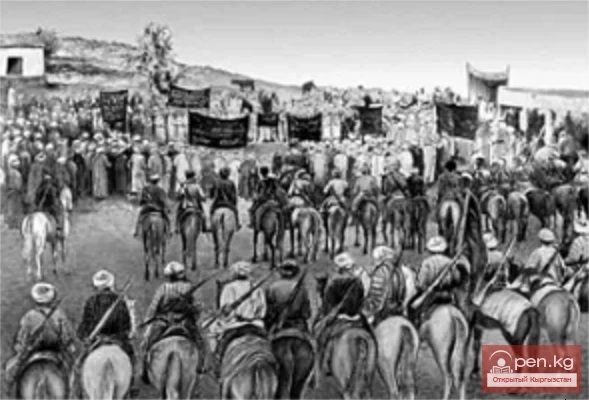

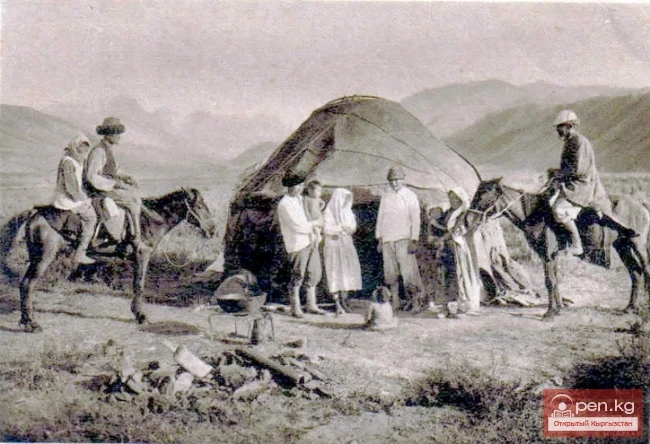

In 1821, ordinary Kazakhs and Kyrgyz inhabiting the Talas Valley rose up against the dominance of the Kokand Khanate. Their numbers reached several thousand people. The uprising gained significant momentum and spread to neighboring areas. It was led by a representative of the feudal nobility, a certain Tentek Tyuro. The uprising became so serious that the khan's authority became genuinely concerned. The rebels occupied the cities of Chimkent, Sayram, and several settlements whose inhabitants joined the insurgents. However, in the decisive battle, Gentek-Tyuro betrayed the rebels and surrendered to the punitive detachment. The uprising was defeated, and its participants were severely punished.

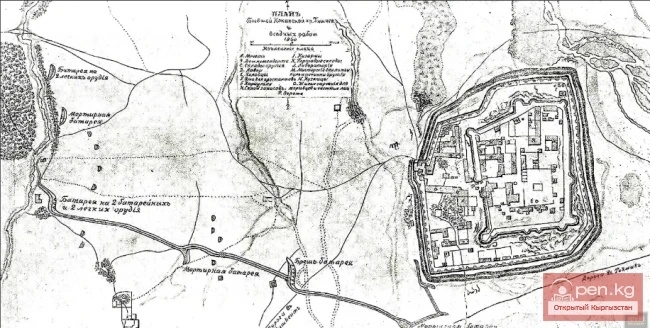

Soon, the Kyrgyz herders roaming the Talas pastures rose up against the Kokand oppression again and occupied the fortress of Yany-Kurgan, where a representative of the Kokand khan was stationed with a detachment. They were joined by Kazakh herders. However, the khan's punitive detachment, commanded by the Tashkent Hakim, managed to crush the resistance of the participants in this uprising. After that, in order to maintain and support the power of the Kokand khan over the Kyrgyz and Kazakhs inhabiting the Talas Valley, a more powerful fortress, Auliye-Ata, was built.

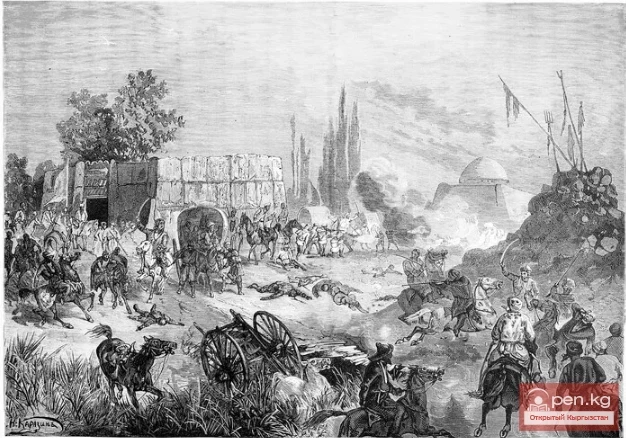

Equally serious was the uprising that arose in the late 1830s among Kyrgyz herders roaming near the Kokand fortress of Pishpek. The trigger for it was the arbitrariness and violence of the khan's tax collectors (zeketchi), accompanied by a military detachment consisting of 300 cavalrymen (sipai).

The uprising engulfed a significant part of the Chui Valley and some adjacent mountainous areas.

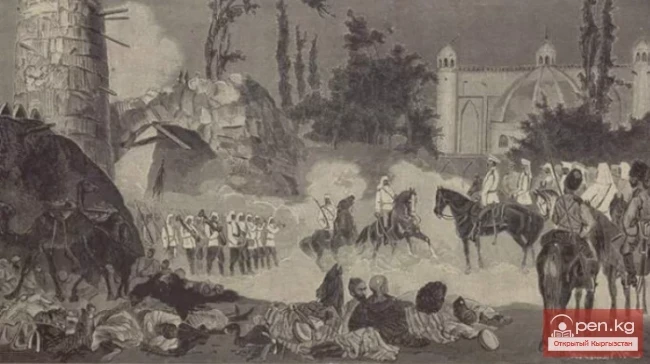

A part of the Kazakhs from the Great Horde joined the rebels. As noted by a contemporary of that uprising, Abu-Abeydilla Muhammad, "The tax payers (the khan's tax levied on livestock—K.U.) rose up, destroyed the entire detachment, and killed Khudai-Berdy Divanbegi," the khan's official who led the tax collectors—zeketchi. Alarmed by this event, the Kokand khan sent a punitive detachment against the rebels under the command of the Tashkent governor (Hakim), who commanded the khan's troops (lyashkari)—Kushbeg. In the ensuing battle, the rebels achieved victory over the punitive forces. The defeated khan's detachment and its commander were forced to retreat. Kushbeg was punished by the Kokand khan and removed from the administration of Tashkent. Meanwhile, the uprising was strengthening and expanding. The victory over the khan's troops inspired the rebels to new successes. However, the unorganized, spontaneous, and poorly armed uprising was defeated in the second battle against a relatively powerful khan's punitive detachment, which suddenly appeared at the fortress of Pishpek, again under the command of lyashkari Kushbeg. The latter "forced them (the rebels—K.U.) to submit again to the authority of the Kokand khan." The actions of the punitive detachment, as always, were accompanied by looting of the indigenous population, cattle theft, and the murder of innocent people. The Kokand khan, frightened by the scale of the uprising, expanded the powers of his governors and increased the number of the military garrison stationed in the fortress of Pishpek, thereby attempting to strengthen his power over the indigenous population.

The Struggle of the Working People of Kyrgyzstan Against Social and National Oppression in the 19th Century.