The uprising was not for the religion of Islam, but for social and national freedom.

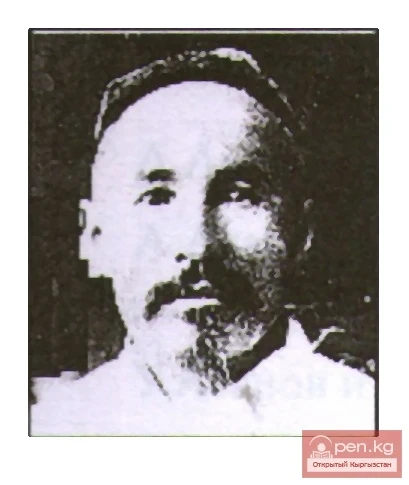

After the expulsion of Khudoyar Khan, the temporary allies of the uprising, Abdurakhman Aftobachi, Isa-Aluie, and other representatives of the feudal nobility, who pursued personal selfish interests unrelated to the interests of the rebellious working masses, proclaimed the obedient Nasr-Eddin as Khan. Information about this can be found in an official archival document. It states: "The clergy and elders proclaimed (as Khan — K.U.) the Khan-zade" (Nasr-Eddin — K.U.). However, the working masses, especially the rebellious common Kyrgyz, "demanded the immediate removal from the throne of Khudoyar Khan's son" (Nasr-Eddin — K.U.). Despite the outrage and indignation of the rebellious workers, Abdurakhman Aftobachi and the feudal lords surrounding him, relying on the military elite of the former Khan's army, left Nasr-Eddin as Khan, while the leader of the common rebels, Pulat Khan, who claimed the Khan's throne, was arrested and imprisoned in the fortress of Makhrama, from where he managed to escape to Chatkal a month later — on August 22, where he hid until the end of September 1875. In essence, Nasr-Eddin Khan was a puppet in the hands of Abdurakhman Aftobachi and his close associates.

The representatives of the feudal nobility, led by Aftobachi and Nasr-Eddin, in order to preserve and strengthen their power, decided to neutralize the uprising for themselves, dull its social edge, direct the workers' movement into a religious channel, and give it an anti-Russian character. They declared a jihad and sent out proclamations and appeals calling on believers, including the population under Russian rule, to a holy war against the Russians in general.

It should be noted that the slogan of the jihad was exclusively associated with the names of Aftobachi and those around him and had nothing in common with the slogans of the rebellious popular masses. This was even reflected in official documents issued by high-ranking Tsarist officials. Thus, in a report from the commander of the troops of the Syr-Darya region dated August 2, 1875, it is mentioned about a conversation with one of the nobles of Nasr-Eddin Khan, Mirza Hakim, who claimed that the jihad was put forward and supported only by Abdurakhman Aftobachi and his associates, and that the popular masses were indifferent to it. Indeed, the Uzbek, Tajik peasants, and Kyrgyz herders, although they were believers, rose up not for the religion of Islam, but for social and national freedom.

Moreover, at that time, the indigenous population in general, and the rebels in particular, had not yet experienced the colonial oppression of the Tsarist power, and their religious feelings had not yet been affected by "infidels." Therefore, they did not support the slogan of jihad.

As can be seen from the above, in the first and early second stages, the uprising in question was directed exclusively against feudal-Khan oppression. The rebels, trying to gain help and support from the Russian authorities, sought to maintain friendly relations with them, although they were unsuccessful in this. "The fact of the expulsion of Khudoyar Khan," emphasizes an eyewitness of this uprising, "did not imply anything hostile to the Russians in the eyes of the Kokandis, as well as our Tashkent authorities (the colonial Tsarist power in Turkestan — K.U.)."

However, the rebels, having convinced themselves that the Tsarist power was hostile to them and openly supported the feudal-Khan oppression against which they were fighting, and having seen how a Cossack detachment under the command of Colonel Skobolev sheltered the fleeing Khudoyar Khan and his nobles, providing them refuge and saving their lives, were forced to fight against the Tsarist colonizers as well. It is no coincidence that the uprising, which engulfed the entire Khanate, soon spread to the Khojent, Kuramin, and some other regions under Tsarist Russia. Divided into several groups of 2-10 thousand or more people, the rebels interrupted on the morning of August 6.

The rebels captured and plundered the glass factory of merchant Isaev and the iron smelting plant of Pozdnyakov. Part of the rebels, moving along the Syr-Darya, occupied Sil-Makhrali and several kystaks, including Parkent, located 40 versts from Tashkent. A number of clashes occurred between the rebels and the Tsarist punitive forces. The serious nature of these clashes is evidenced by the fact that in just one clash on August 2, the rebels lost 500 people killed and many wounded. There were also losses on the side of the punitive forces. A group of rebels, consisting of 4,000 Kyrgyz nomads led by Mumyn, acted energetically. "On the morning of August 9, the rebels attempted to capture the cities of Khojent and Ura-Tyube. Everywhere, the local population joined the uprising. All this posed a serious threat to the Tsarist colonial authorities. The Turkestan Governor-General Kaufman, feeling the strength of the popular uprising and leading the actions of the Tsarist punitive forces against the rebels, noted that "the flame of the then Muslim movement covered a vast area" and all the population of the Kokand Khanate, as well as several regions of the Turkestan Governor-Generalship." He also emphasized that the wide scope and mass character of the uprising, the sympathy and support it received from the population under Tsarist rule — "all this represented a very difficult and serious situation for us at first."

The Tsarist colonial authorities were very alarmed. They took urgent measures to suppress the uprising. A punitive detachment of 5,000 soldiers and Cossacks was quickly formed. This detachment included 18 infantry companies, 8 Cossack hundreds, and one sapper unit. They were also provided with 20 artillery pieces. The detachment included dzhigits led by the beks of Shahri-Zab and Kusht. The entire punitive force was personally commanded by the Turkestan Governor-General, General-Adjutant von Kaufman, while the command of individual units was entrusted to Generals Golovachev, Bardovsky, Trotsky, Colonel Skobolev, and other Tsarist officers. In addition, Kaufman announced a call for the indefinite and temporary release of individuals living in Tashkent, from which 2,200 people were gathered and sent to guard postal and telegraph lines.

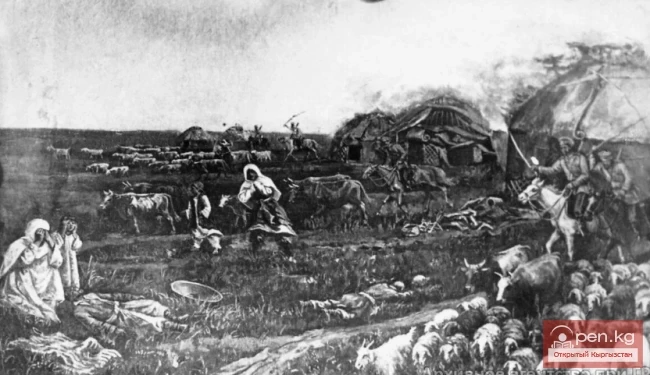

The escape of Khudoyar Khan from Kokand in 1875