The Influence of Kokand Colonization on the Kyrgyz

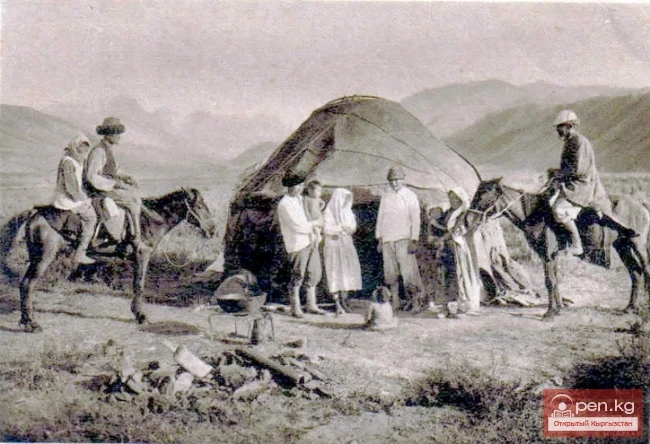

The Kokandis encouraged the Kyrgyz to settle in specific locations, forming sedentary or semi-sedentary kystaks. The Kyrgyz came under the constant attention and control of khan's officials, and their wintering habits tied them to certain places; in the event of uprisings or revolts, the Kyrgyz found themselves surrounded by Kokand forces.

Animal husbandry was also promoted by the Kokandis, as the army needed cavalry, and the settled population required meat for sustenance. Horse breeding and sheep breeding were encouraged: horse breeding provided good riders, as the Kyrgyz were predominantly called to serve in the khanate's cavalry and constituted a significant part of its most mobile troops. There was even a special Alai detachment in the khanate. The cavalrymen, whose ranks were called dzhavan, were required to appear on their horses.

In one of the Kokand documents regarding the enlistment of cavalrymen, there was a directive to the responsible official: "Accurately write down in each kishlak the wealthy and strong young men (skilled riders), in goat fights (buzkashi), subjects (fukara), if they have good, fast horses. The lists of future warriors even noted the color of the horses they rode. For the Kokandis, relations with the Kyrgyz were expressed not so much in securing their territories and pastures but also in attracting the Kyrgyz with livestock into their domains, as taxes were levied on livestock. In 1859, the Kokandis, having collected the tax - zyakhet - from the livestock of the Bugins, promised to build a mound on the River Tyup to protect them from the Sarybagysh, but suggested that the Bugins descend from Tekes to their previous pastures in the Pre-Issyk-Kul region.

"Feeling quite free in the impregnable mountains during the summer, the Kyrgyz were forced to descend for wintering and here succumb to the power of Kokand garrisons, 'who then rob them,'" reported the Kazakh K. Bedegiev, who was captured by the Kyrgyz in 1834.

The large migrations of the Kyrgyz were linked, in addition to the search for better pastures, with the desire to avoid the dangerous pressure and oppression of the Kokandis. The khan Janatay, who was migrating in the Chuy Valley in 1863, fearing the threat from the Kokandis, intended to migrate towards the Kunghey-Alatoo and appealed to the Russian authorities that if they granted him the Kebeny area, he would abandon Kunghey. The request was based on the fact that, traditionally migrating to Kunghey, he would at that time enter Kokand territory and thus become a Kokand subject and khan's debtor, while receiving permission for the Kebeny area would allow him to remain a Russian subject.

The khans sought to suppress migrations through harsh punitive measures as well as by enticing Kyrgyz feudal lords with gifts. In one of the letters on behalf of the Kokand khan, the Kyrgyz manaps Janatay and Baytik were invited "with all their volosts and herds" to migrate within the limits of the khanate. To attract them, Koychi, a Kyrgyz from the Karabagysh clan, was sent with gifts.

Some authors believed that the line of fortifications built by the Kokandis from Tashkent to Almaty was the result of a well-thought-out plan for military-economic expansion against the nomads, and that thanks to these fortresses, the Kokandis cut off the nomadic steppe from the mountain summer pastures and placed the nomads under the dependence of Kokand garrisons.

We believe this position is fundamentally incorrect. Firstly, the line of fortresses did not cross the migratory routes from the steppe to the mountains but ran parallel to them, as it could even conditionally be called a border between Kazakh and Kyrgyz migrations. Secondly, their goal was not to cross the paths but to collect zyakhet, for which fortresses were established in places where nomads concentrated for wintering. Thirdly, the fortresses and "colonization" did not affect or interfere with the internal economic life.

Thus, having examined the issue of the influence of the Kokand Khanate and Kokand colonization on the economic life of the nomads and animal husbandry, one can conclude that this influence was minimal. No significant changes occurred in the centuries-old traditional livestock economy of the Kyrgyz within the Kokand Khanate or due to its dependence. Of course, this also did not contribute to the spread of the Kokand variant of Sunni Islam among the Kyrgyz nomads.

The Long Process of Transition of the Kyrgyz from Nomadism to Agriculture