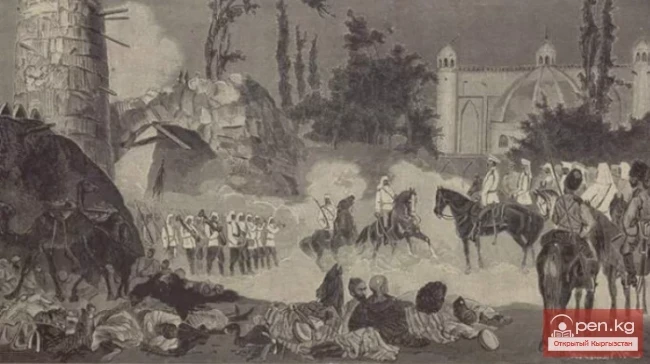

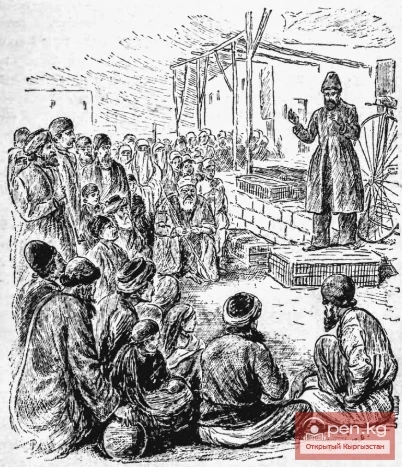

Uprising of the Masses in 1873-1874

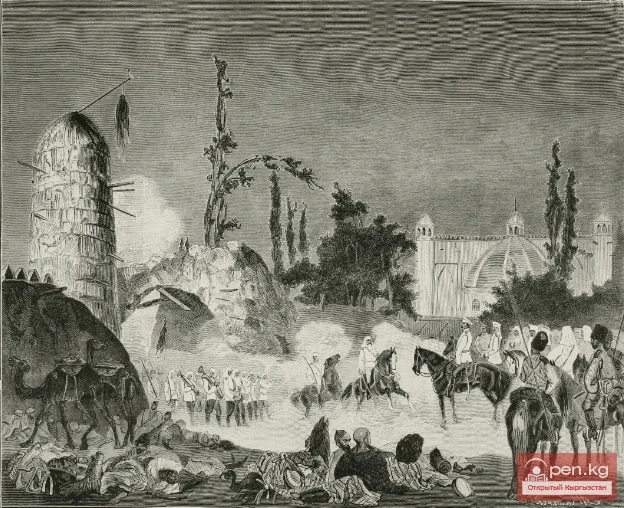

This uprising was distinguished from the previous one by its scale, mass participation, duration, and historical consequences.

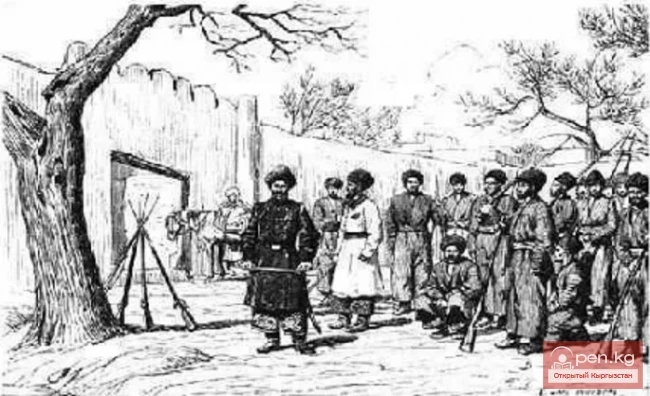

The cause of the uprising was the increasingly oppressive feudal and khanate rule, the arbitrariness, and violence of the Kokand Khan and his officials. This is clearly illustrated in a letter from the rebels themselves (written in the autumn of 1873), addressed to the head of the Khojent district. In it, we read: "The Khan began to act against the Sharia, which stipulated that one sheep should be collected as tax for every hundred rams. However, the khan's tax collectors—zyaketchi, who arrived in the spring of 1873 to the Kyrgyz nomads, began to forcibly collect three rams for every hundred heads. For this, unable to bear the injustice, we robbed his (the Khan's - K.U.) zyaketchi." Even a high-ranking tsarist official, who supported the authority of Khudoyar Khan and his son Nasr-Edin and was closely monitoring the course of the uprising, was forced to note that the constant levies and cruelty of Khudoyar Khan had recently so enraged all ethnic groups and classes in the khanate that the poor and oppressed subjects of the Khan resolved to throw off the hated burden at any cost.

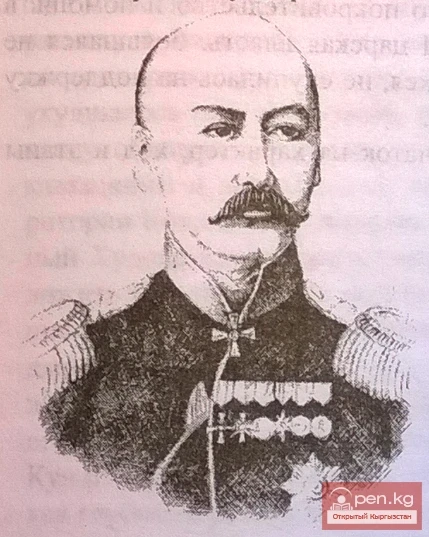

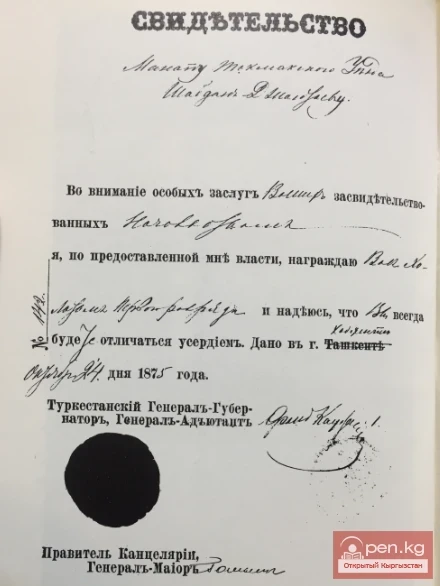

The tsarist governor, General-Adjutant von Kaufman, who systematically received reports on the course of the uprising of interest to us and led the punitive expeditions, wrote in his secret report of 1881, under the pressure of reality, that "since 1873, a whole series of uprisings and disturbances in the khanate began, caused by the cruelty, greed of the Khan, and the exorbitant taxes and levies imposed by the ruler of Kokand on the population."

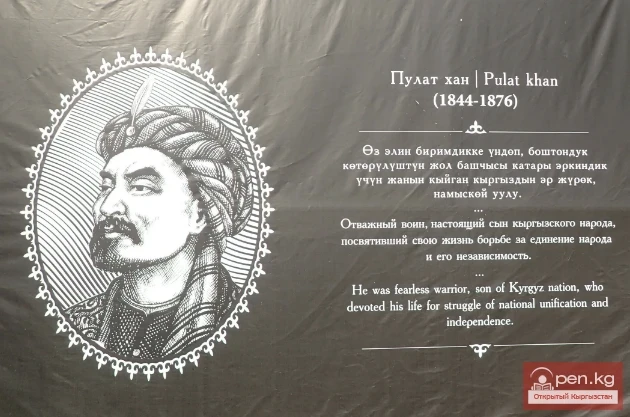

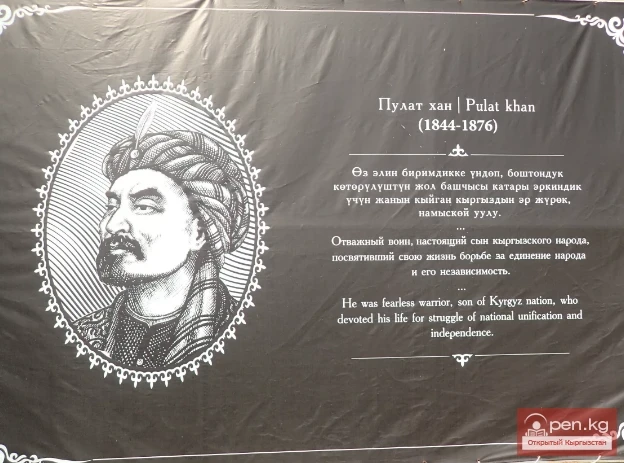

Similar information can be found in the work of the famous orientalist and eyewitness of this historical event A.A. Kuna and in the testimony of one of the leaders of this uprising, Mullah Iskak Hasan oglu (Pulad Khan). These are not isolated examples. The main influx of written evidence about the events occurring in the Kokand Khanate came from correspondence through the colonial administration of the region. The historian's attitude towards it should, of course, be cautious and critical. It is not possible to take all the information contained in this correspondence at face value.

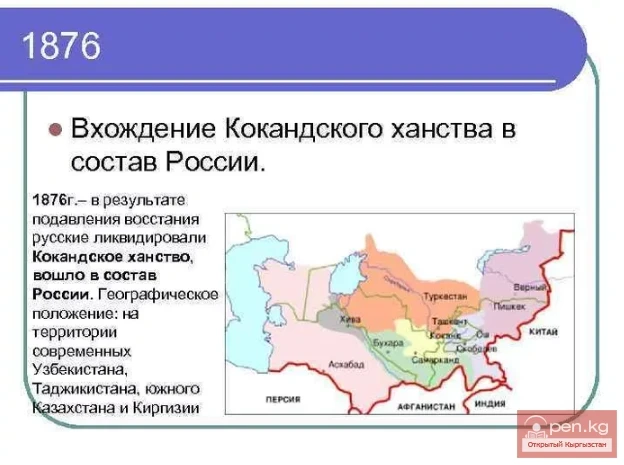

The attitude of representatives of the colonial administration towards the uprising of 1873-1876 was complex, cautious, and not always consistent, sometimes even contradictory. Closely monitoring the development of events, the colonial administration and the Petersburg noble circles did not immediately determine their final approach to the course of the uprising in 1873-1876. The very scale of the uprising, its popular character could not but worry the tsarism and its Turkestan administration, and even more so evoke sympathy for the rebels. There was a danger that the uprising could extend beyond the khanate. In this context, individual documents from the colonial administration could exaggerate the coverage of events or, conversely, soften it, be biased, etc. Nevertheless, the totality of the informational material contained in the documentation can undoubtedly serve as a vivid testimony to the socio-liberation basis of the popular movement of 1873-1876 and confirmation that its main cause was the terrible oppression and wild arbitrariness of the authorities of the feudal-despotical Kokand Khanate.

The Uprisings of the Kyrgyz in the First Half of the 1860s