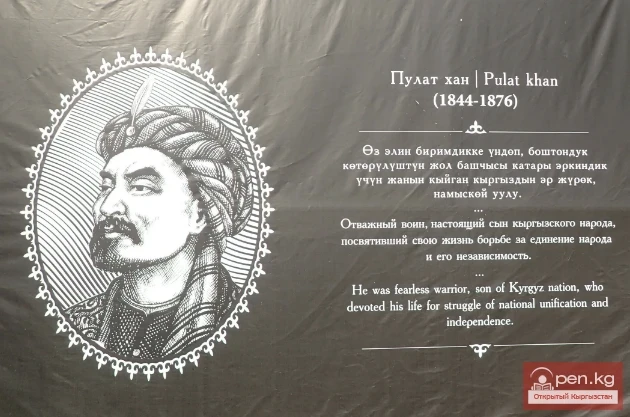

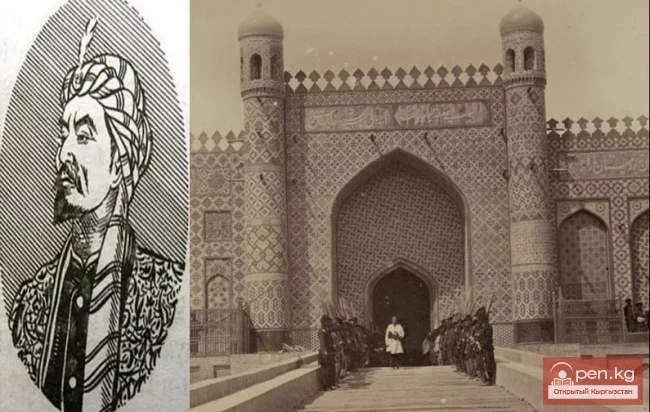

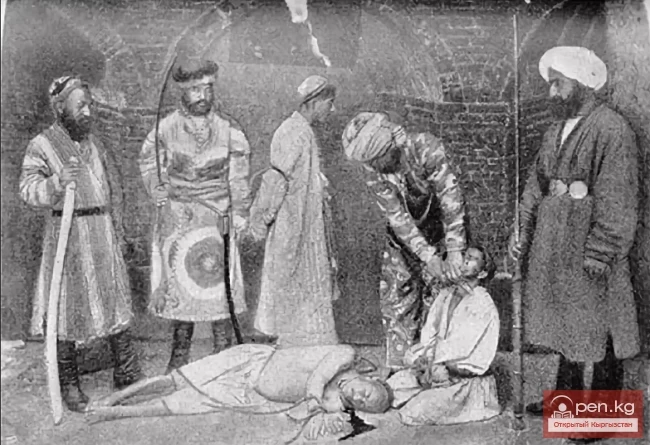

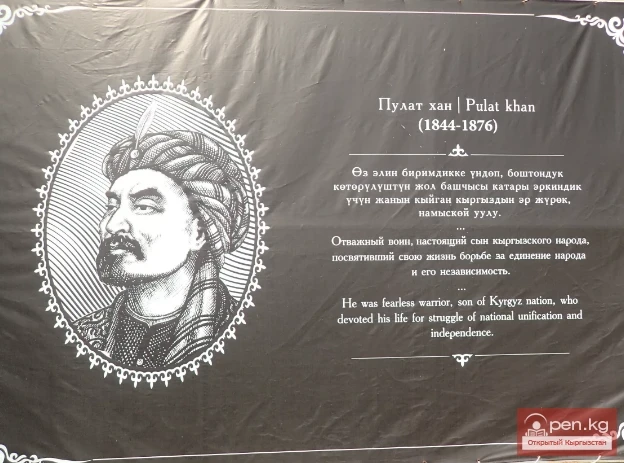

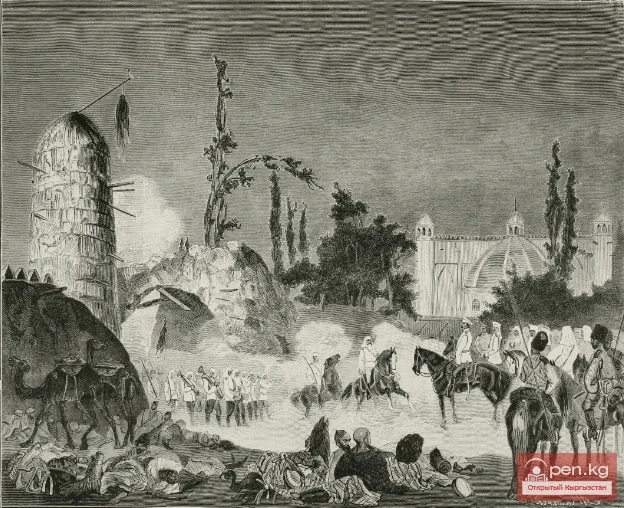

Execution of Pulat-khan

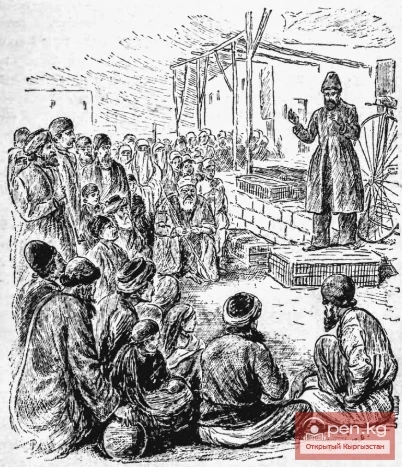

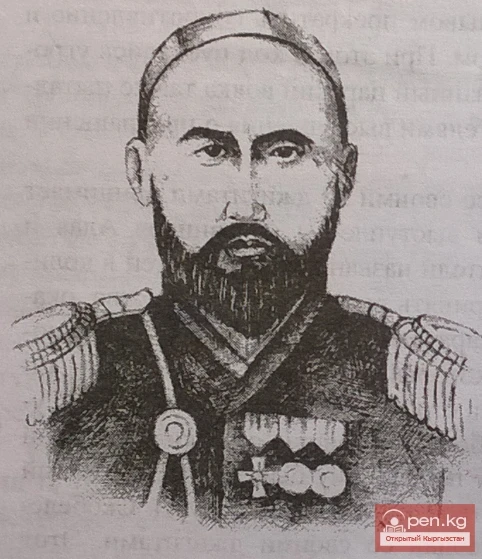

The day after the defeat at Uch-Kurgan, the city nobility of Margilan, trying to please the victors and save their own skins, appeared before the commander of the punitive detachment, expressing submission, and handed over 15 weapons belonging to the rebels led by Pulat-khan. The commander of the punitive detachment, Major General Skobelev, concerned that the uprising could flare up again, urgently organized a special group that included representatives of the feudal nobility from Margilan, Osh, and other regions. He sent it with 30 horsemen, instructing them to capture Pulat-khan and deliver him to the city of Andijan.

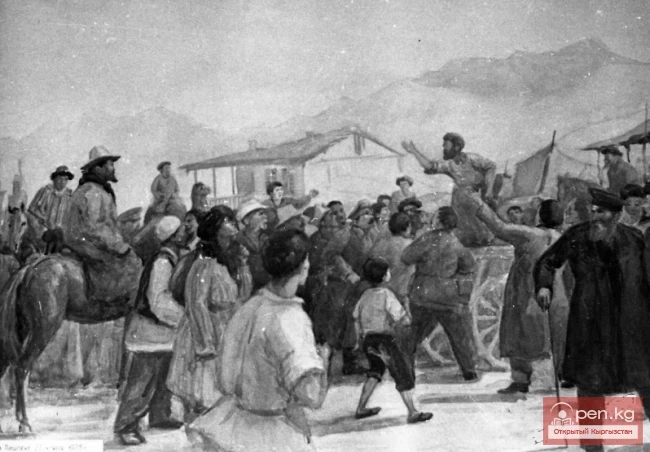

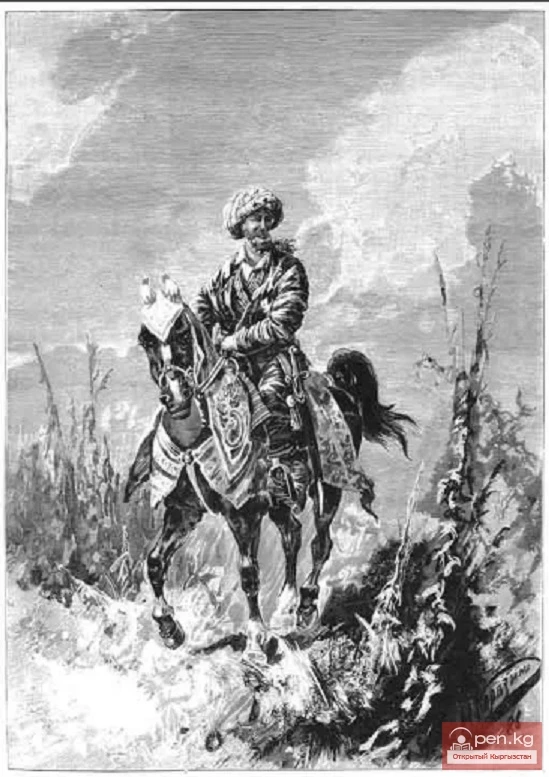

On the night of February 18 to 19, after a shootout, this group managed to capture Pulat-khan and bring him to the designated city. In Pulat-khan, the tsarist authority saw not only the leader of the national liberation uprising but also an irreconcilable enemy. It is no coincidence that the Turkestan Governor-General Kaufman, who was then in St. Petersburg, hastened to send a telegram ordering the immediate hanging of Pulat-khan in Margilan and generously rewarding those who betrayed him into the hands of the tsarist authorities. The representatives of the tsarist authority decided to execute Pulat-khan publicly to intimidate those present and discourage them from further uprisings. For this purpose, on the morning of March 1, residents of Margilan and the surrounding kystaks were herded into the palace square — urdu. Several thousand people gathered here. Pulat-khan calmly listened to his death sentence the day before, on February 29, said "hop" — good, and after having dinner, went to bed. The next morning, he was led to the scaffold. He walked slowly, limping on his injured leg, carefully observing the gathered crowd as if bidding them farewell. Before the scaffold, the executioners hurriedly grabbed him by the shoulders, but Pulat-khan proudly brushed their hands away and said: "Why are you in such a hurry? Don't you see that my leg hurts? You'll have time!" And he climbed onto the platform himself. Pulat-khan died with great dignity as a national hero. Thus, at 12 o'clock on March 1, 1876, one of the loyal and prominent leaders of the uprising, Mulla Iskak Asan Ogly, who took the name Pulat-khan, was executed.

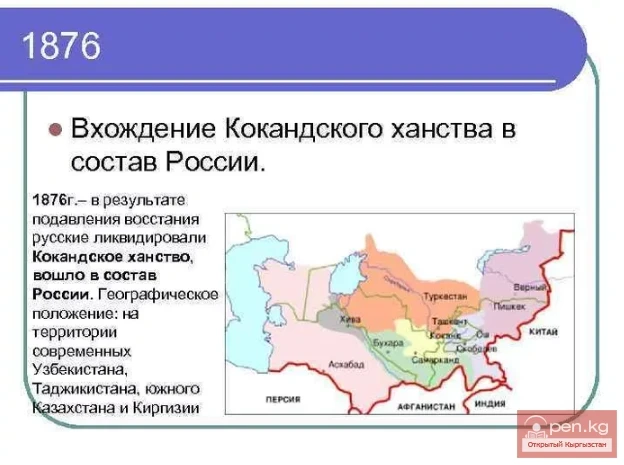

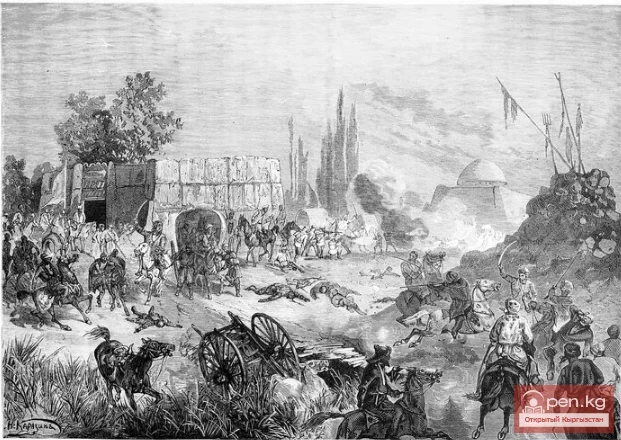

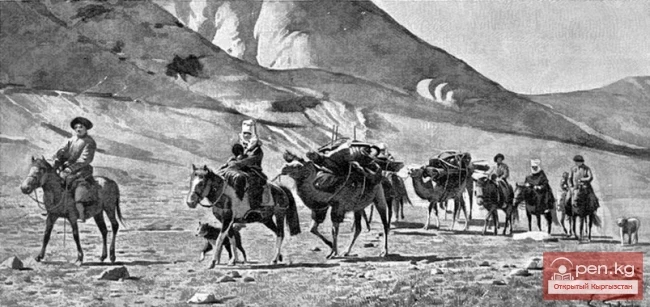

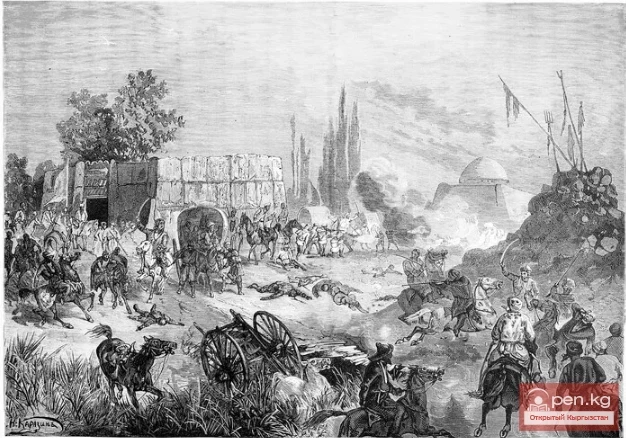

From late January to mid-February 1876, the uprising was suppressed. However, the participants continued to resist the punitive forces. Some skirmishes and clashes still occurred. For example, on March 26 of that year, in the Kara-Kiya area south of the kystak of Sukh, the rebel Kyrgyz, numbering more than 800 people, engaged in battle with a detachment of 42 Cossacks and 25 riflemen commanded by Colonel N.I. Korolkov. But the insurgents, having lost several dozen killed and wounded, were forced to retreat. There were also separate uprisings that, however, could not gain wide scope or cover more or less significant areas of the region.

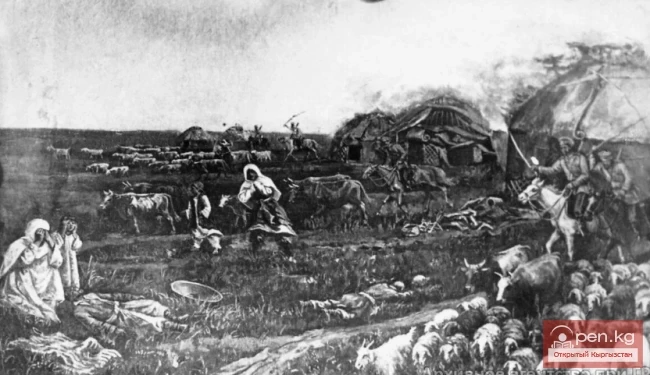

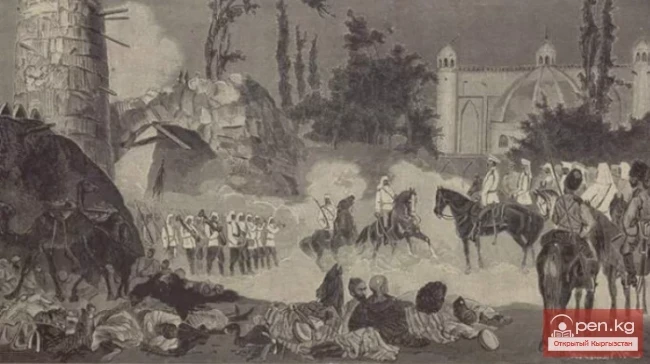

As can be seen from the above factual material, both khan's and tsarist troops exhibited great cruelty in suppressing the uprising of 1873-1876. They literally passed through the areas engulfed in the flames of the uprising with sword and fire, drowning popular uprisings in blood. The cruelty was exhibited not only by the khan's military leaders but also by tsarist generals, particularly Skobelev. Considering the brutal suppression of the uprising by the tsarist troops, Academician Ponomarev B.N. notes that Skobelev conducted "punitive expeditions to Central Asia." Criticizing certain individuals who attempted to idealize the aforementioned tsarist general, Doctor of Historical Sciences A. Yakovlev writes that some authors "presented the tsarist general Skobelev in an obviously romanticized form, without taking into account his reactionary mindset and role in suppressing popular uprisings in Central Asia."

The total number of tsarist troops acting against the rebels in 1875-1876 reached up to 20,000. At the head of these punitive forces were tsarist generals, including Skobelev, known for his cruelty. He spared neither children, nor the elderly, nor women. Skobelev and other tsarist generals ruthlessly burned ails and kystaks, wiping them off the face of the earth, killing and plundering unarmed residents solely to instill fear in the indigenous population, to teach them a harsh "lesson," to discourage them from the liberation struggle, and to break the free-spirited spirit of the people. For them, the war with the rebels was extremely advantageous. It served as a source of glory and military merit, distinctions, and orders, and quickly promoted them in military service. It is enough to say that Skobelev began his military actions against the insurgents as a colonel and, before he could deal with the uprising, was "promoted" to the rank of major general in the tsarist army. The same can be said about Kaufman, who held all the threads of military operations of the tsarist punitive forces in suppressing the uprising in question. In terms of cruelty, he was no less than Skobelev. It is no coincidence that F. Engels, in his work "Anti-Dühring," wrote about him that "General Kaufman attacked the Tatar tribe of Omud in the summer of 1873, burned their tents, and ordered their women and children to be slaughtered, 'according to good Caucasian custom,' as stated in the order..." Kaufman's cruelty and that of the punitive detachments he led were no less vividly manifested in suppressing the uprising under study.

As a result of the bloody actions of the khan's and tsarist punitive forces, the adult population of the southern part of Kyrgyzstan and the Kokand Khanate significantly decreased. Academician Midendorf A.F., who specifically surveyed the Fergana Valley and its population in the wake of the uprising, emphasized that "in age categories between 15 and 40 years, the number of women significantly exceeds the number of men. This is explained by the fact that during the suppression of the uprising in 1875, a large number of able-bodied Karakyrgyz fell." For example, in the kutluk-seit and kytay clans, before the uprising, there were an average of 5 people in each family, but after the suppression, the family consisted of only 3.15 souls, i.e., it decreased by 1.85 people. A similar picture was observed in other Kyrgyz clans and among Uzbeks who participated in the uprising.

Defeat of Pulat-khan at Uch-Kurgan