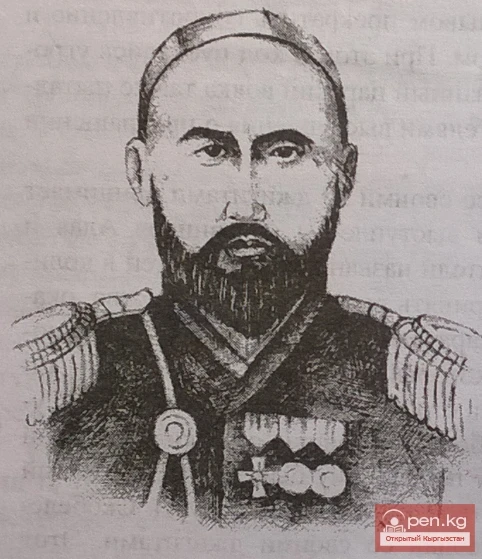

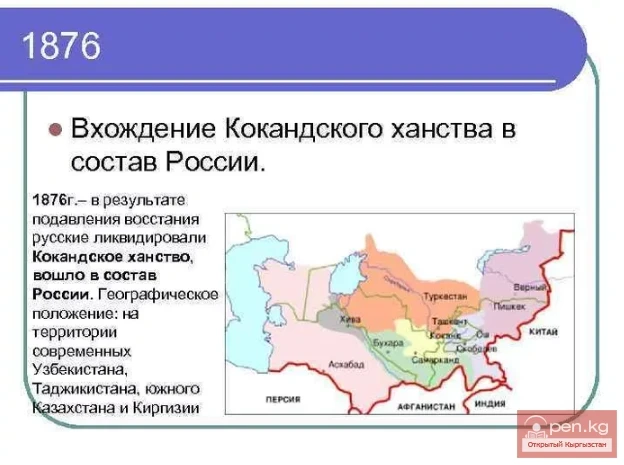

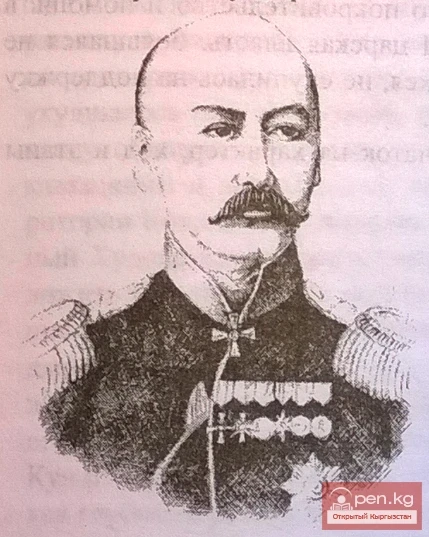

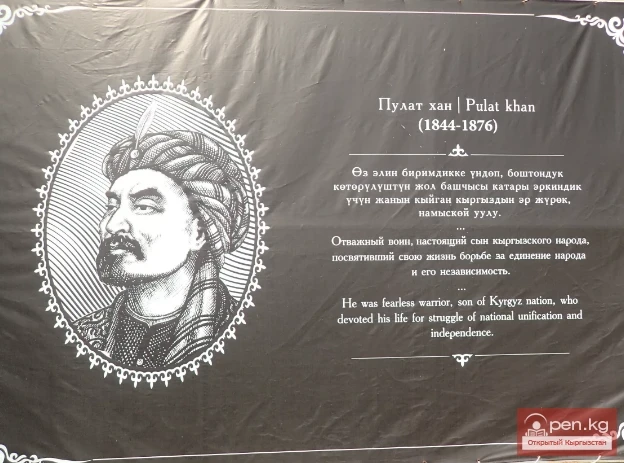

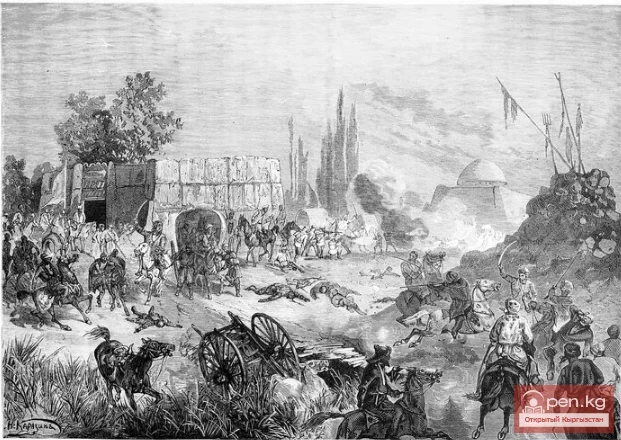

As is known, after the abolition of the Kokand Khanate, Kurmanjan Datka, along with her sons, unwilling to submit to the imperial government, took a desperate step—an unequal struggle against the imperial troops. In this regard, during the final stage of the conquest of the khanate, the Governor-General of Turkestan, K. D. Kaufman, wrote that "never before in Central Asia had the Russians experienced such a long and stubborn struggle. For the first time, we encountered an energetic fighter and learned that fighting with the population is incomparably more difficult than with the despots of the native khanates." In such a difficult time, in July 1876, General M.D. Skobelev called upon Shabdan-Baatyr and his horsemen to participate in a military-scientific expedition to Alai. It is not hard to guess that the experienced general, with the help of Shabdan-Baatyr, wanted to conduct the campaign with minimal losses. In turn, Shabdan-Baatyr wished to save his southern compatriots from inevitable defeat by participating.

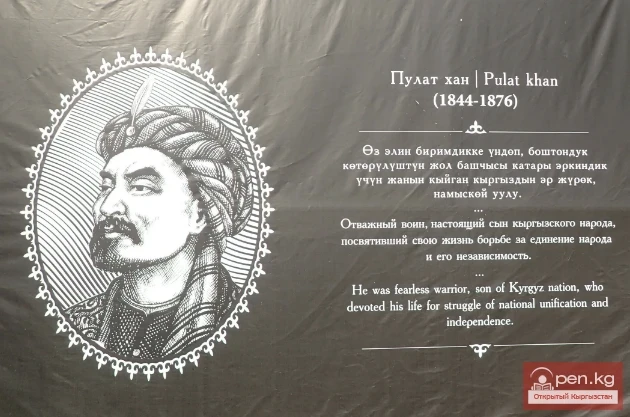

Thus, indeed, thanks to the participation of Shabdan-Baatyr, the military campaign was resolved relatively peacefully, and the uprising of Pulat-Khan was quickly suppressed. Through Shabdan's brother, Abdrakhman, Skobelev sent a letter on July 21 to Abdildabek, the son of Kurmanjan Datka, who continued the struggle. He was offered to lay down arms and cease useless resistance. Abdildabek's response is interesting: "To His Excellency Skobelev! We have received your letter about the truce. Until now, with the help of Allah and His prophet, we have resisted by gathering people because you constantly violate the obligations you have taken upon yourself... You, starting from Tokmak, have conquered the Kyrgyz, Kipchaks, Sart, made promises, but after the capture of Kokand, everything changed. If you had not broken your promises, there would have been no uprising. If you truly desire peace and intend to keep your promises, then give the task to Shabdan-Baatyr. We also express our trust in him. Let Shabdan-Baatyr resolve our issues. It is all up to you, but if you leave Shabdan in the Osh district, it is possible that order will be established between us." As we can see, Abdildabek fully trusted Shabdan as a mediator and intended to end the struggle, but he still did not agree to peace.

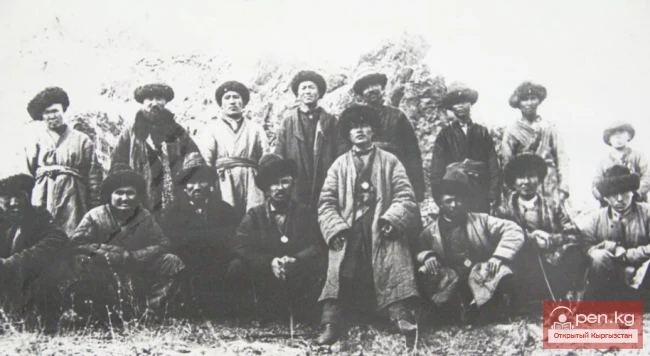

From July 29 to 31, Russian detachments, accompanied by Shabdan, continued to pursue the rebels. A tale has been preserved about the meeting between Abdildabek and Shabdan-Baatyr, where they, having discussed the situation, came to the conclusion that it would be advisable for the rebels to flee to Afghanistan.

The Role of Shabdan-Baatyr in Kurmanjan Datka's Move to Her Native Pastures

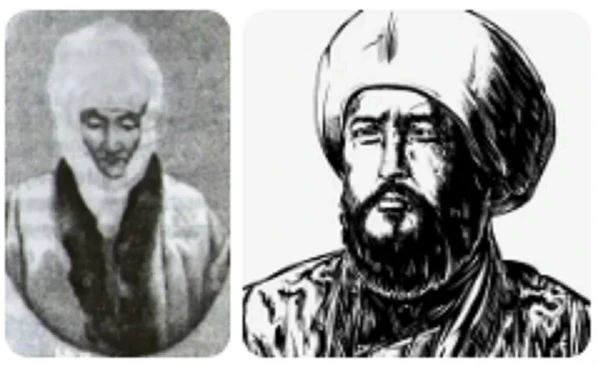

During these same days, on the orders of M.D. Skobelev, Major M.E. Ionov's detachment was searching for Kurmanjan Datka and found her on July 29 with her entourage in the Kok-Suu area with her brother Ismandiyarbay. After brief negotiations, Kurmanjan agreed to meet with the military governor of the Fergana region, M.D. Skobelev. The "Queen of Alai" arrived in Lyangar at the governor's headquarters accompanied by her son Kamchybek and grandson Myrzapayaz. M.D. Skobelev received her with honors and asked her to convince her sons to return to Alai, promising to ensure their safety. In response, she promised that "peace and quiet will reign in the Alai valley as long as she lives."

Realizing the futility of resistance, Kurmanjan proposed that the rebel detachments return to their native pastures. Following her advice, many Kyrgyz, including the sons of Makmuthbek, Asanbek, and Batyrbek, returned to the Osh district. All of them were appointed as volost administrators.

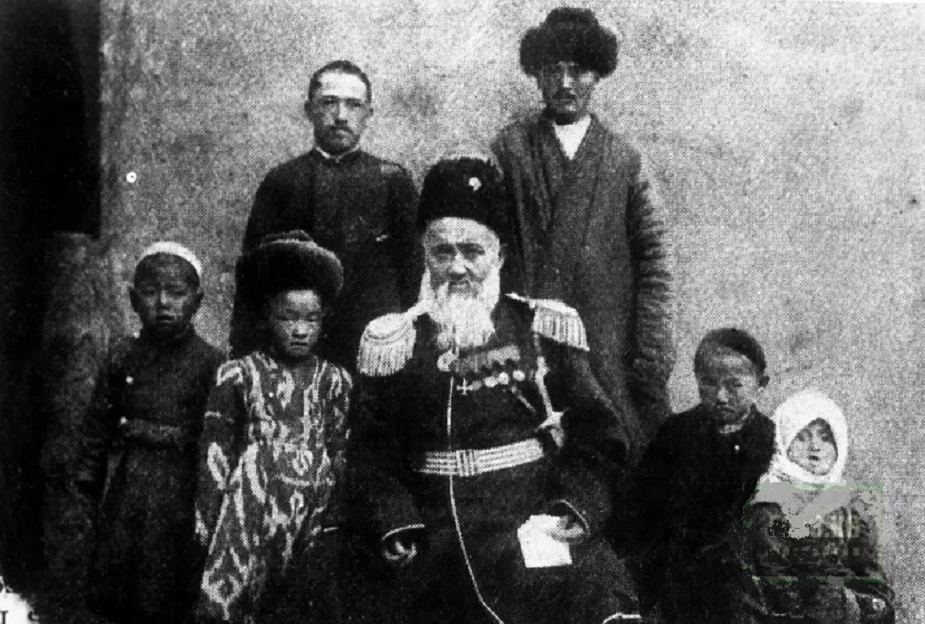

According to the recollections of Shabdan's son, Kemel, when Kurmanjan Datka was at General Skobelev's headquarters, the Kyrgyz colonel set up a large white yurt for the clan leader and honored her for a month according to her rank and status. He sincerely admired the upbringing of this great woman. Every morning, both politicians discussed the situation in the region.

It is likely that they were searching for ways to save and consolidate the Kyrgyz people. Moreover, it should be emphasized that the interlocutors treated each other with respect.

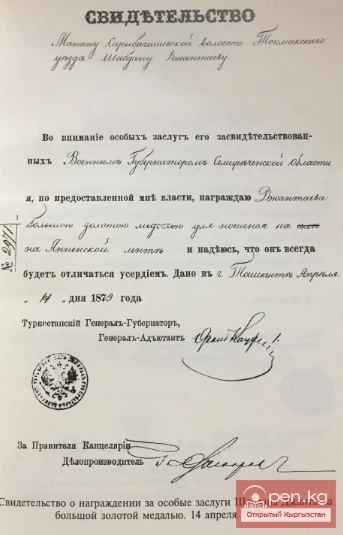

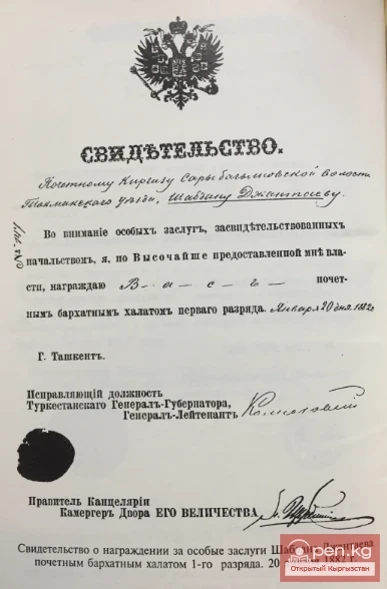

We can add to this the assertion of the contemporary Kyrgyz historian T.N. Omurbekov. He believes, based on a number of facts, that Shabdan-Baatyr played a significant role in Kurmanjan Datka's move to her native pastures—Gulchu. Such information is also found in the work of the first Kyrgyz historian B. Soltonoev. This primarily speaks of the friendly relations between the two outstanding public figures and politicians. They maintained the most amicable relations in the following years as well. In the interests of the people, they supported friendly ties with many local representatives of the imperial authority. And those, knowing their authority, were forced to take their opinions into account. Thus, according to the data of Osmonaly Sydykov, Shabdan-Baatyr contributed to the release from captivity of 73 of his compatriots.

Once again about Shabdan