Attracting Kurmanjan Datka to the Side of the Tsarist Authority

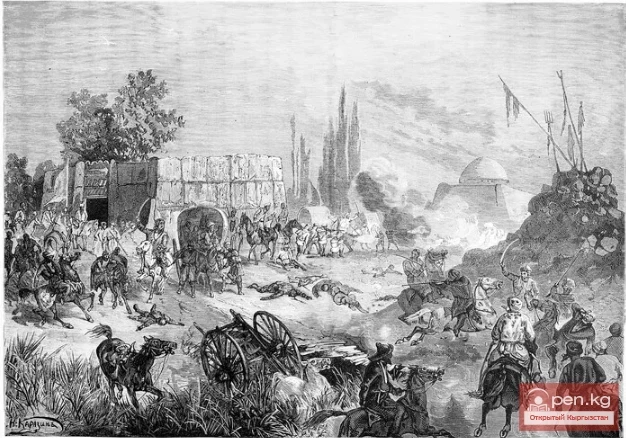

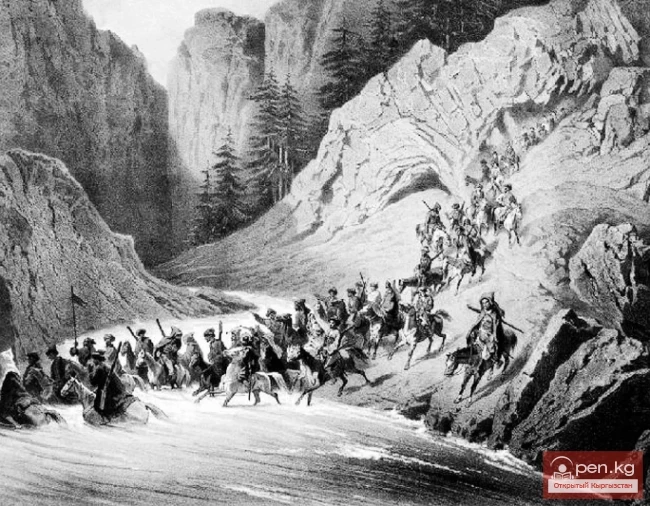

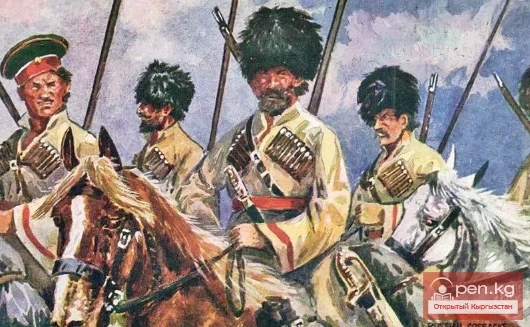

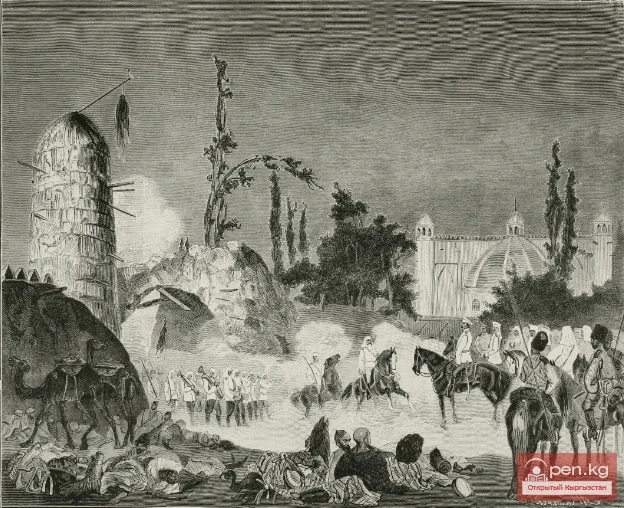

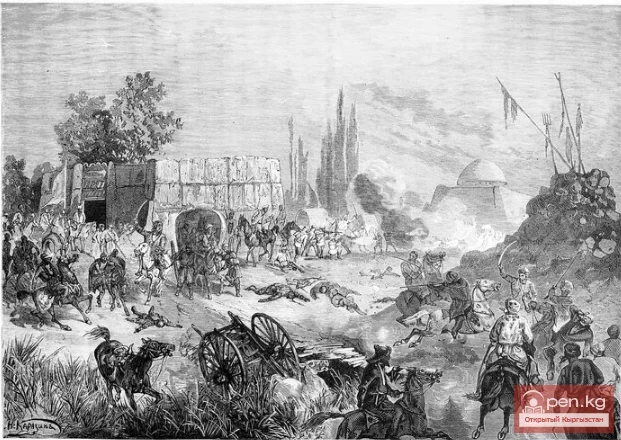

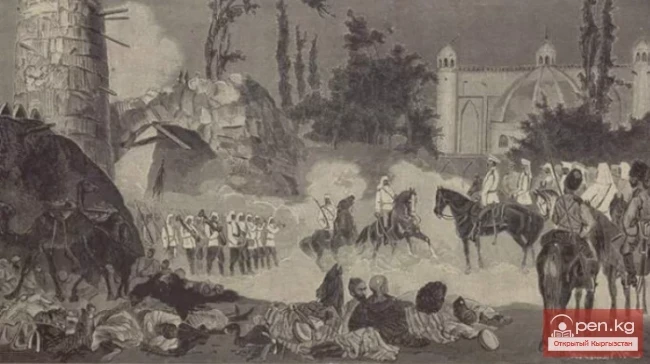

On April 25, 1876, punitive forces approached Yangy-Aryk, where the participants of the uprising were vigorously preparing for a decisive resistance. The rebels blocked the path leading to them, set up several rows of stone barricades, and dismantled the bridge over the river. They believed their position was impregnable. However, they soon saw the punitive detachment, and a battle ensued. As noted in an archival document, a "strong and accurate fire was opened on the punitive forces, and it became apparent that this ridge was occupied all the way to the top by numerous enemies (the rebels—K.U.), who were hiding behind stone barricades." It was not easy to deal with the rebels, who occupied a strategically advantageous position and offered strong resistance to the tsarist detachment. An eyewitness of this campaign, Tageev V.L., wrote that "the position of the Kyrgyz was impregnable."

They, hiding behind stones and barricades, inflicted heavy damage on us, so much so that Skobeleva soon had to realize the impossibility of attacking the mountaineers, and he decided to make a flanking maneuver." Nevertheless, the punitive forces continued their attempt to take the rebels' position by storm. Climbing up the steep rocky height, they reached halfway, where they were met by the rebels with "strong fire and a hail of stones." The participants of the uprising, aiming to deliver a strong blow to the punitive detachment, "ran in dense crowds towards them (the punitive forces—K.U.) from behind the ridge of the mountain."

However, "after two hours of stubborn fighting," they managed to occupy the first row of the stone barricade. Nevertheless, the participants of the uprising, hiding behind the remaining barricades on the height, continued to offer stubborn resistance and strike at the punitive detachment. This could not be denied even by a high-ranking tsarist official like Kaufman. In his most humble report for 1877-1888, he wrote: "The enemy (the participants of the mentioned uprising—K.U.) fought well and, taking advantage of the terrain, showed great resilience." The commander of the punitive detachment, Major General Skobeleva, convinced of the impossibility of taking the height by storm, decided to find a way around and strike the rebels from the side they did not expect. In this regard, the punitive forces were aided by a certain Imankul, who pursued his personal interests and betrayed the uprising. He pointed out a flanking route to the punitive detachment to the rear of the defenders. However, the participants of the uprising continued to offer stubborn resistance. The punitive forces managed to capture the indicated position and drive the rebels out of there.

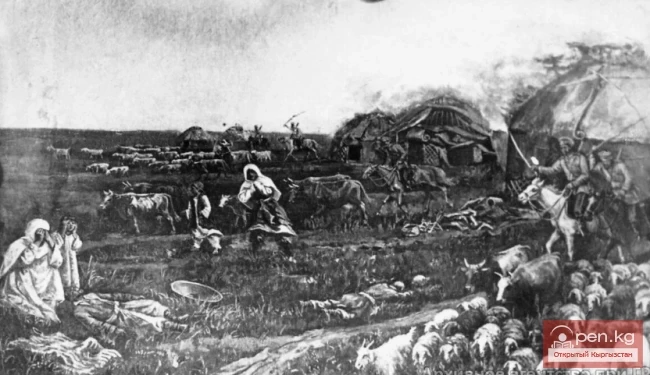

The latter, leaving more than 150 killed on the battlefield, were forced to retreat. The number of wounded rebels was significantly higher. The punitive detachment lost 3 men killed and 21 wounded.

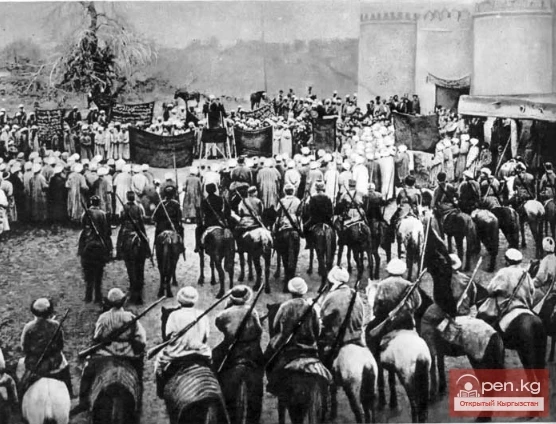

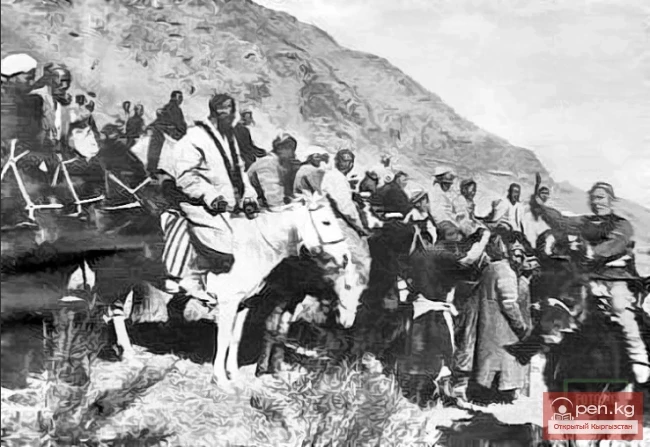

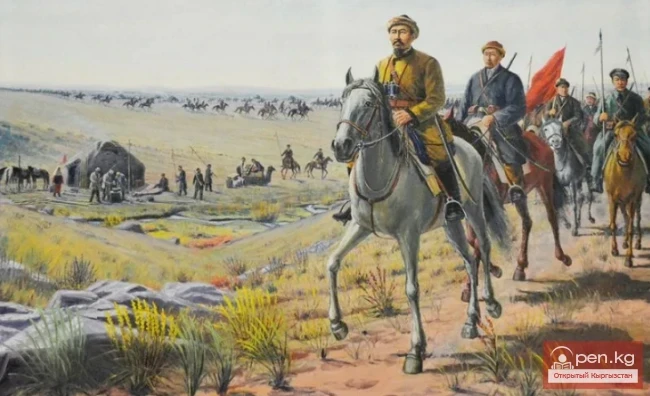

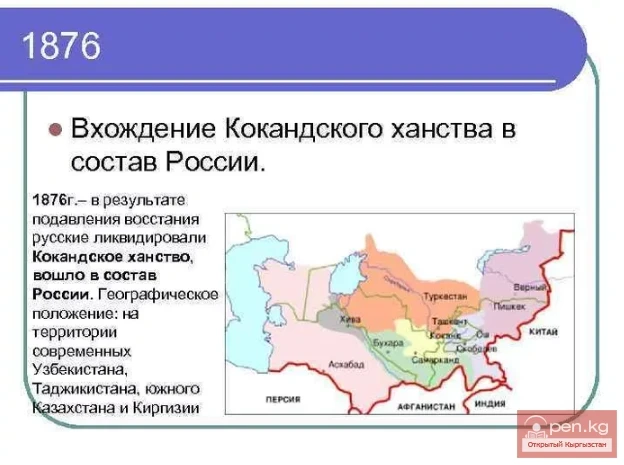

After the defeat, Abdullabek, along with his brothers Mahmudbek, Asanbek, and their associates, fled to the Kyzyl-Art pass and hid in the Pamir mountains. Kurmanjan Datka, who ruled the population of Alay and Gulcha with her son Kamchybek, her nephew Murzapayaz, and some other individuals, tried to leave the region and hide beyond its borders. But she fell into the hands of the tsarist punitive forces, led by Prince Witgenstein, who brought her to Gulcha and presented her to Major General Skobeleva. The latter, seeing in Kurmanjan Datka his social support, decided to attract her to his side. She was given a warm welcome with a rich dastarkhan, i.e., a feast.

Skobeleva gifted Kurmanjan Datka a brocade robe and offered her and her sons "warm" positions. The sons of Kurmanjan Datka, except for Abdullabek, were appointed as volost administrators. She was referred to as the "Queen of Alay" and effectively continued to govern this area, maintaining her authority over the indigenous population.

Kurmanjan Datka and her sons were forced to serve the colonial authority. They "brought great benefit to our (tsarist—K.U.) government," emphasized V.L. Tageev, who knew her well. The pages of the periodical press of that time noted that Kurmanjan Datka did everything to keep the Kyrgyz from unnecessary bloody clashes and tried to persuade her sons to return to their homeland and serve the colonial authorities, which was indeed done. To anticipate, it should be noted that the tsarist colonial authority, preserving and supporting the social privileges and influence of Kurmanjan Datka, generously rewarded her with valuable gifts. She received several honorary brocade robes, gold watches with a diamond crown, and other valuable gifts. She was also assigned a pension of 300 rubles per year.

Anti-colonial movements of the indigenous inhabitants of the region in the 1880s-90s