Reasons for the Start of the 1916 Uprising Against Tsarist Autocracy by the Peoples of Central Asia

Pishpek, which served in the late 19th century as a place of exile for those deemed undesirable by the tsarist government for political reasons, became one of the centers for the spread of illegal revolutionary literature and the activities of social democracy in northern Kyrgyzstan. In 1903, Marxist-Leninist literature was distributed by Viktor Ivanovich Loytser, who had been exiled from Saratov. In 1904, a group of teachers led by Ivan Matveevich Khlebov conducted revolutionary propaganda among the townspeople and peasants from surrounding villages. He headed the "Society of Sobriety" in Pishpek.

In Pishpek, a revolutionary worldview was forming, and the revolutionary activities of Mikhail Vasilyevich Frunze began. As a student at the St. Petersburg Polytechnic Institute, in 1905 he participated in a peaceful demonstration along with 140,000 workers from St. Petersburg. The tsarist autocracy brutally suppressed the peaceful march, killing over a thousand people and injuring around two thousand. M. V. Frunze, then 19 years old, was also injured. "The stream of blood shed on January 9," M. V. Frunze wrote to his mother in Pishpek, "demands retribution.

The die is cast. The path is determined. I dedicate myself to the revolution."

Revolutionary protests against the tsarist administration also occurred in Pishpek in 1905. Leaflets were distributed at rallies. In 1907-1908, revolutionary work among the city's residents was carried out by exiles I. S. Svinukhov and F. E. Panfilov. A significant role in the development of the revolutionary movement was played by a group led by A. I. Ivanitsyn, who worked in the irrigation management of the Chui Valley, where about 200 workers were employed.

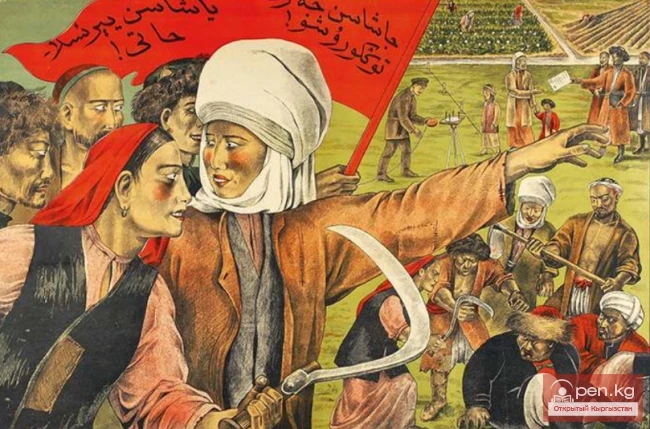

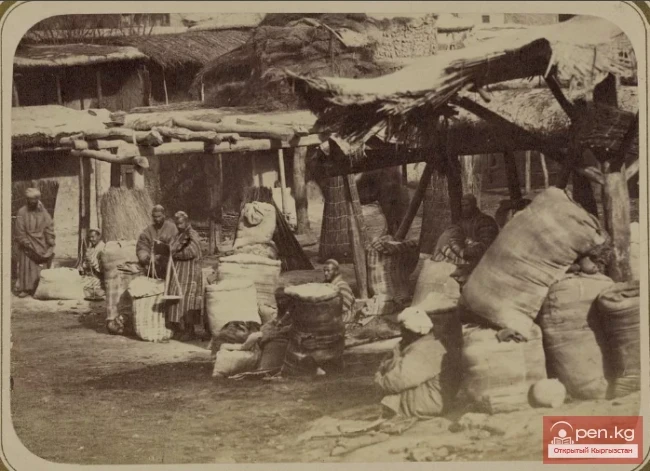

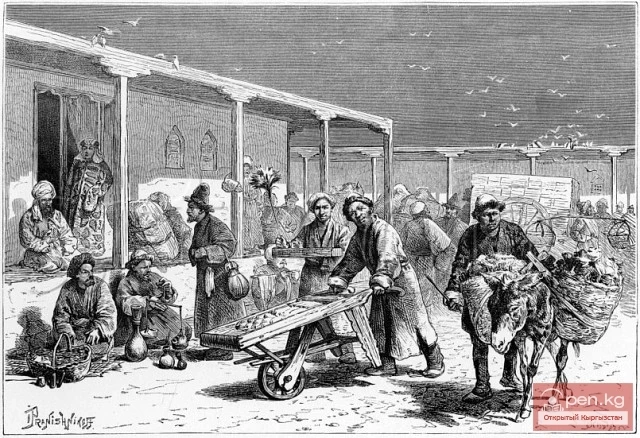

In Pishpek and the surrounding district, colonial administration had dominated for over 50 years, gradually shifting from a policy of restriction to a policy of depriving landowners and local feudal lords of property rights. There was an intensified policy of resettling peasants from Central Russia and organizing their land use at the expense of seizing fertile lands from the Kyrgyz population. The rights of Kyrgyz people to land use were sharply curtailed. The tax policy of the colonial administration became harsher. All of this served as the main reason for the start of the 1916 uprising against the tsarist autocracy by the peoples of Central Asia.

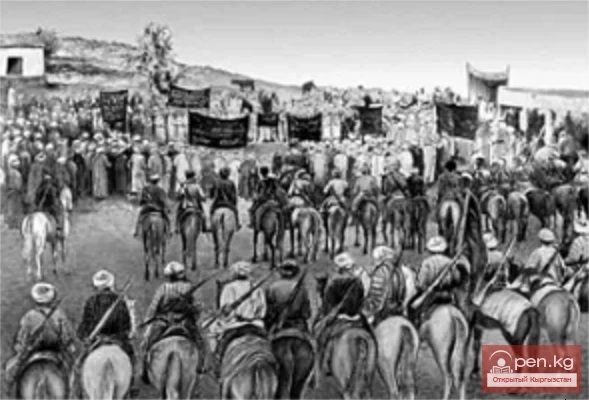

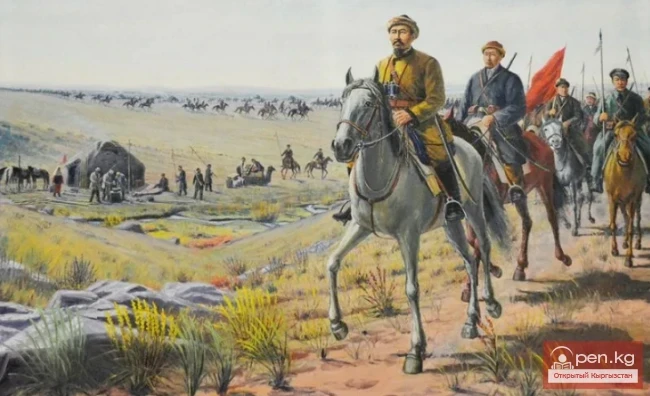

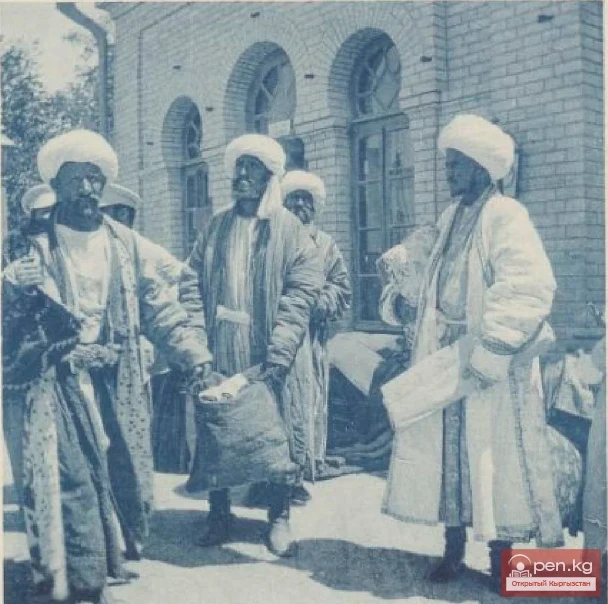

Armed uprisings were particularly strong among the population of northern Kyrgyzstan against the colonial administration. Representatives of tribal nobility in the outskirts of Pishpek, who became leaders of the rebels, were elected as khans.

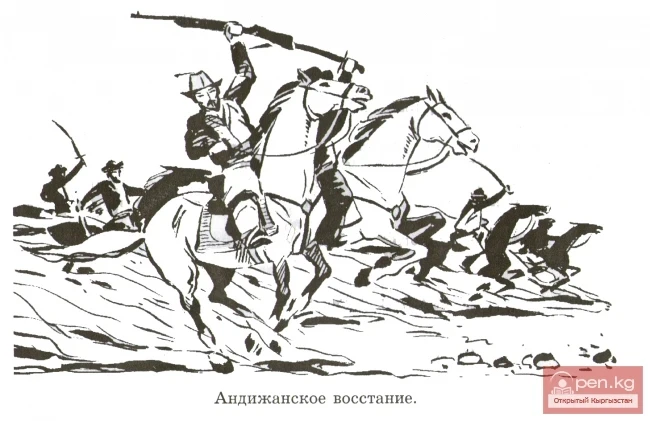

For example, on August 11, 1916, in the Pishpek district, the leader of the Sarybagysh tribe, Mokush Shabdanov, was proclaimed khan by the population. One of the leaders of the armed group, Ibraim Mergen (a sniper), engaged in an unequal battle in the Boom Gorge with soldiers from the punitive detachment escorting a convoy with ammunition on seven carts and seized it. The rebels obtained 200 Berdans with a large number of cartridges, which armed the participants of the uprising from the Kochkor and Jumgal valleys, and part of the Issyk-Kul basin.

In many places affected by the uprising, the activities of the local colonial administration were completely paralyzed, and the participants of the uprising aimed to rid themselves of the colonial administration and achieve state independence.

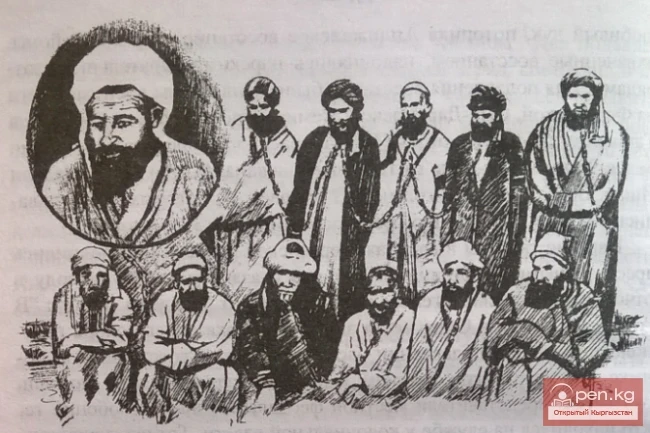

Colonel Rymshiev, the Pishpek district chief, adopted a series of repressive measures against the participants of the uprising: on August 9, 1916, Bektursun Begaliyev was arrested for spreading rumors about the impending uprising of the Kyrgyz, and a double-barreled shotgun was confiscated from him. During the period from October 16 to 20, 1916, the leaders of the Kyrgyz uprising were arrested and imprisoned in the Pishpek prison: from the Shamsinskaya volost — Osmonaly Baigaziev, from the Tyuleberdinskaya volost — Mamyrkul Esenaliev, from the Kochkor volost — Sarybai Dyikanbaev, from the Abildinskaya volost — Suranchi Karasaev, from the Suusamyr volost — Jumali Boktaev, as well as a group of Kyrgyz from the Issyk-Ata and Tynayev volosts.

On the same days, on October 12, 1916, junior officer K. T. Yelistaratov and private A. E. Taranenko from the 243rd Samara detachment, gathering groups of rebellious Kyrgyz with children, attempted to convoy them to the Kegetin outpost. The Kyrgyz attacked them, killing Yelistaratov, and Taranenko was seriously wounded. The rebels seized two rifles from them.

However, the participants of the uprising were poorly armed and did not pose a serious threat to the heavily armed punitive detachments of the tsarist autocracy. The uprising was suppressed with extreme brutality.

Russian kulaks took an active part in its suppression. When the resistance of the rebels was broken, a bloody retribution began: rebels were slaughtered by the thousands, and women and children were exterminated. The Kyrgyz population lost almost everything: land, livestock, and their yurts were burned.

Fleeing from inevitable death, the Kyrgyz and Kazakhs rushed to the Chinese border. They suffered serious losses during their flight, caught by the advancing winter. The difficult mountain passes of Bedely and Bekkeritik in the Tian Shan were strewn with corpses of people and fallen animals for almost 300 versts.

From the Pishpek and Przhevalsk districts alone, 110,000 to 120,000 people fled, and the situation for the Kyrgyz who did not manage to escape across the border was dire. There began an intensified displacement of the Kyrgyz from their settled areas, and Cossack stanitsas and settlements were formed in these territories: Samsonovskaya, Kegetin, and Nikolayevskaya in the Pishpek district.

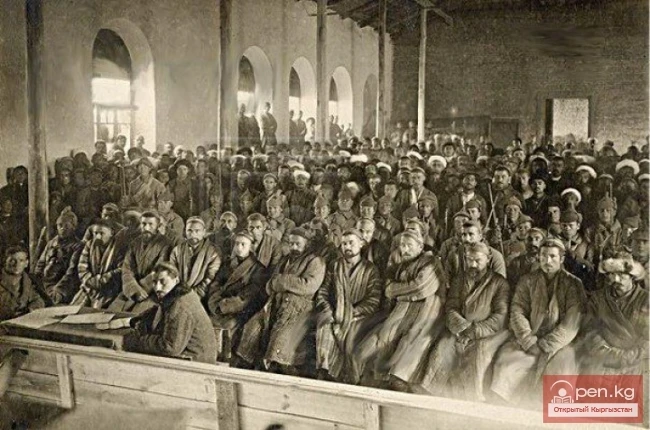

Captured participants of the uprising were imprisoned in the Pishpek prison.

Despite the fact that the uprising was defeated, it undermined the foundations of the colonial policy of tsarism and became one of the links in the pressure of revolutionary forces against autocracy. The 1916 uprising occurred during the First World War (1914-1918), in which the participation of the Russian Empire exacerbated the political crisis in Russia and contributed to the revolutionary upsurge in the country and the growth of the national liberation movement on the outskirts of Russia. The defeat of the tsarist troops on the German-Russian front led to the victory of the bourgeois-democratic revolution in Russia in February 1917 and the overthrow of the tsarist autocracy. The territory of the Russian Empire began the democratization of state and public life.

Rapid Development of Pishpek in the Late 19th Century