Andijan Uprising.

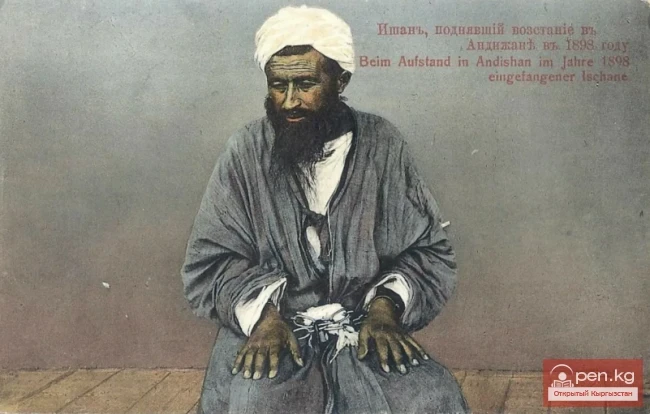

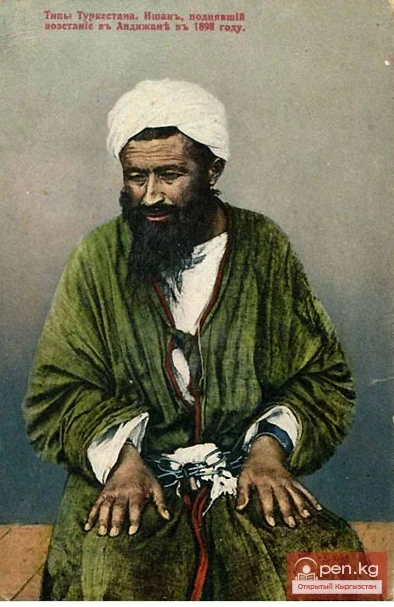

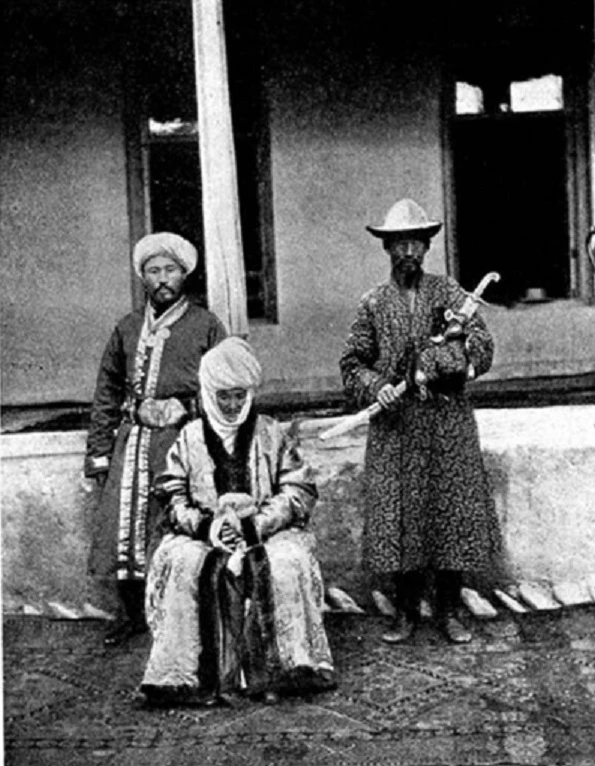

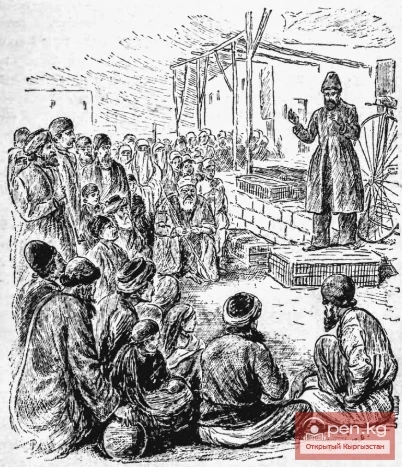

The main reasons for the uprising were unbearable living conditions and the arbitrariness of the tsarist authorities. On May 17, 1898, closer to evening, people began to gather in the village of Min-Tyube — Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, Tajiks. Gradually, their number reached 200 people. The village ishan (religious leader) Madalі — a well-known and respected man who had made a pilgrimage to Mecca — spoke with anger about how the Russians brought drunkenness into the lives of Muslims, destroyed morals, closed mosques and madrasas, persecuted the Islamic faith, and turned the faithful, that is, Muslims, away from the laws of Sharia. The people murmured. “The oppressors profit by taking away the cotton we grow. And the people, who have cultivated it with their labor and sweat, grow poorer year by year. Can we continue to live like this?” — Madalі implored the gathered crowd. “We can no longer endure! Until the Russians are expelled, life will not improve. It is better to perish fighting than to endure such violence. We must go to Andijan!” — the people began to shout.

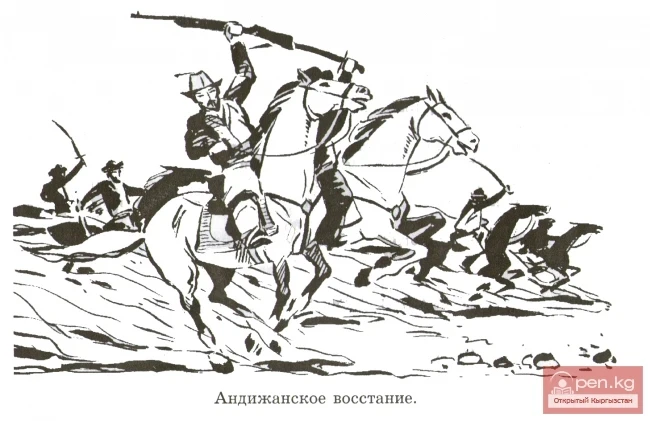

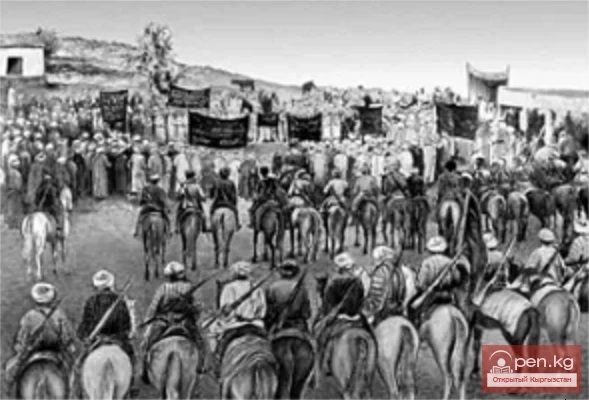

Led by Madalі, the crowd moved towards the city. Along the way, residents of other villages joined them. The people were armed with pitchforks, sticks, homemade spears, and some carried rifles. Their numbers reached 2,000 people.

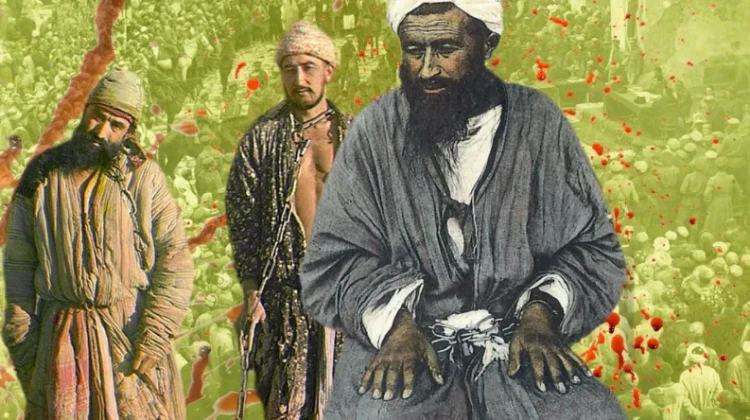

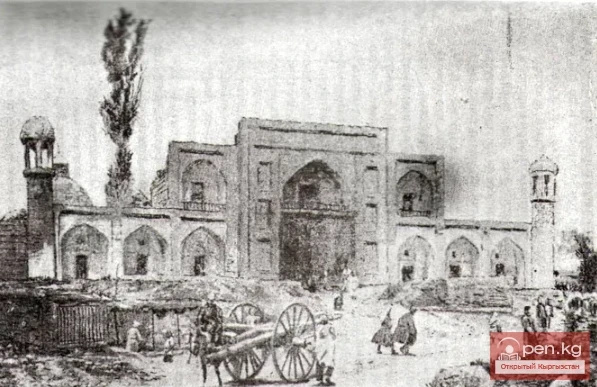

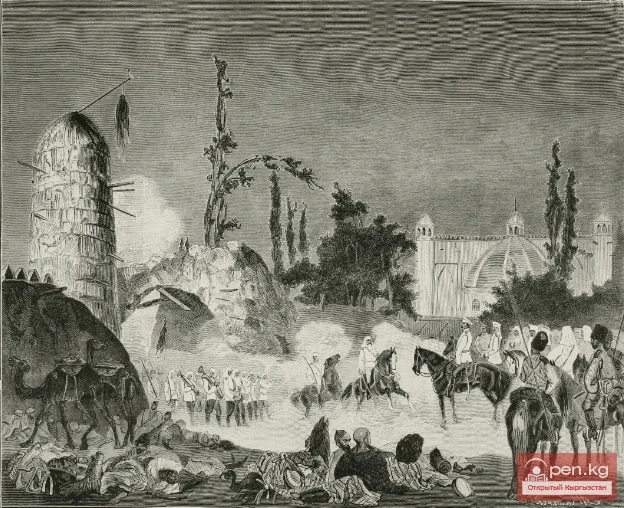

Around 3 a.m., the rebels entered the city and attacked the garrison of tsarist soldiers. In a fierce battle, more than 20 soldiers and officers were killed. The rebels, almost unarmed, also suffered heavy losses and were forced to retreat. Isan Madalі was captured.

The uprising spread like wildfire throughout the Fergana Valley. However, the tsarist troops managed to suppress the leaderless people within a week. About 800 people were arrested, of whom 415 were brought to trial. Isan Madalі and 18 participants of the uprising were hanged, while 362 rebels had their death sentences commuted to many years of hard labor and were sent to Siberia. Among them was the famous Kyrgyz akyn Toktogul Satylganov, who fell into the hands of tsarist soldiers due to the denunciation of enemies.

Tsarism brutally suppressed the uprising. The village of Min-Tyube, which became the center of the uprising, was razed to the ground, and a Russian village was built in its place. Despite the defeat, the Andijan Uprising had great historical significance. It was the first step towards the national liberation struggle of the local population of Turkestan against the colonial policies of autocracy.

The Uprising of 1916. The Beginning of the National Liberation Struggle. Year after year, the tsarist authorities tightened the already unbearable conditions. The introduction of a military tax and the continued confiscation of land for settlers further exacerbated the situation. Exhausted by taxes and the inhumane treatment of the authorities, the people were ready to take up arms. The pretext did not take long to appear.

On June 25, 1916, by the highest decree of the tsar, a directive was issued to conscript men of draft age — from 19 to 43 years old — from the local population of the Turkestan region for work on the construction of defensive structures in areas where the army was operating. Defeated in World War I, Russia sought to ensure free and compliant labor for the needs of the front and to somehow strengthen its positions.

The governor-general of the region, giving instructions to his assistants, said: “The local population interests us as material for servicing Russian peasants, so we must instill in them a respectful attitude towards all Russians.

Those who refuse to comply will be deprived of land, will die in poverty, or Russia will part with them.” The directive effectively confirmed the official colonial policy of tsarist autocracy towards the local population.

The people perceived the will of the white tsar with hostility: the elders did not want to send their sons far from their native land. The situation was aggravated by some of the settlers, frightening the Kyrgyz Muslims with the prospect of having to eat pork in rear work and that they would all perish in the trenches under a hail of bullets... And the people took up arms. The directive only added fuel to the fire.

The main reasons for the uprising were economic and political: ruthless exploitation of the poor by the rich, the introduction of ever new taxes, the impoverished existence of the majority of the people, their lack of rights, and the intensification of national oppression by tsarist autocracy.

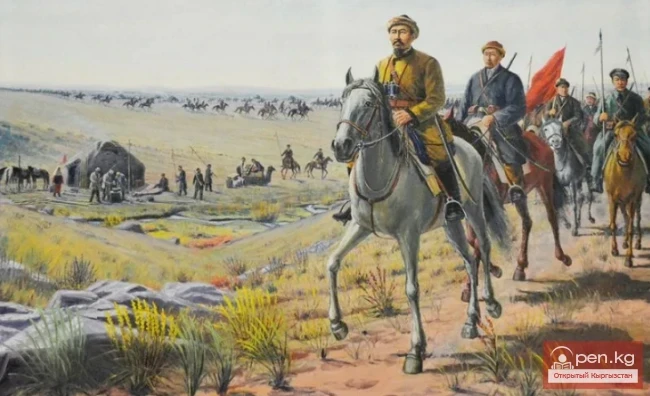

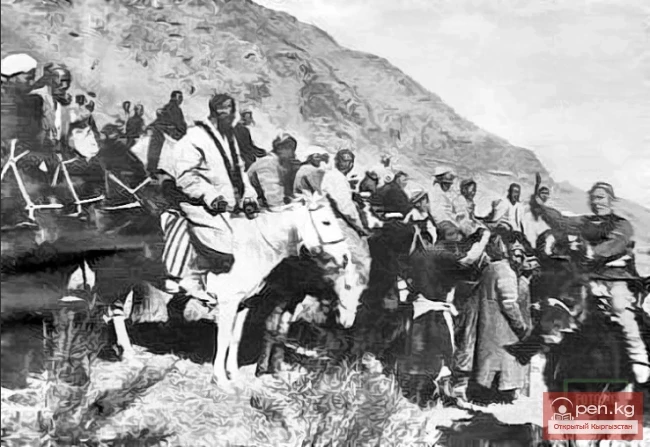

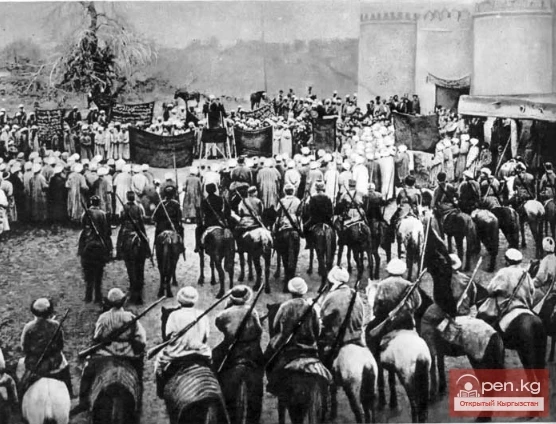

The Rise of the Liberation Movement and Its Outcomes. Unrest began in July 1916 in the city of Khojent and spread throughout Turkestan. The most significant uprisings against tsarist arbitrariness occurred in the Pishpek and Przhevalsk districts of the Semirechye region. On August 7, the population of the Pishpek district rose up, and on August 9, residents of the mountainous areas: Suusamyr, Kochkor, Jumgal, and Naryn joined them. From August 10 to 12, unrest engulfed the population of the Issyk-Kul region. Fierce clashes between the rebels and the tsar's troops continued from August to October.

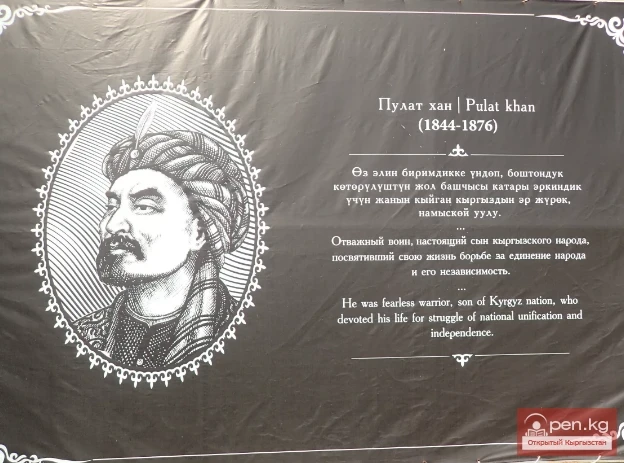

The Kyrgyz united, declaring one of their authoritative and influential relatives their khan, and under his leadership fought against the tsarist troops. The Kemin Kyrgyz chose the son of Shabdan batyr — Mokush as their leader, the Issyk-Kul Kyrgyz chose Batyrkan Nogoy uulu, and the Kochkor Kyrgyz chose Kanat Ybyke uulu.

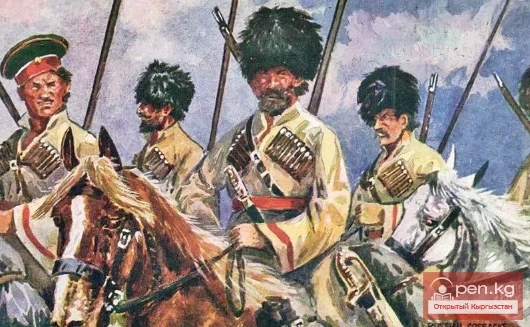

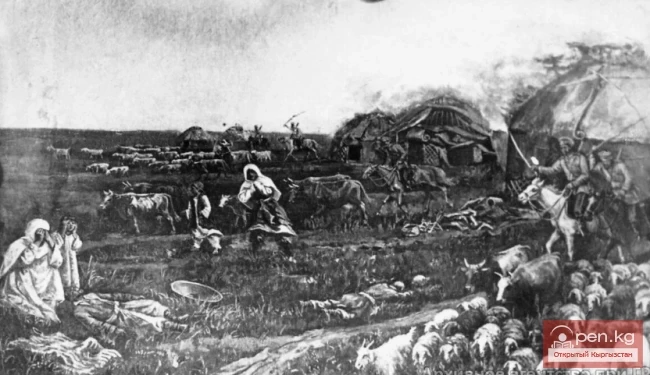

To suppress the uprising, troops from Semirechye were dispatched, as well as two cavalry regiments sent from central Russia, a horse battery, 35 companies, 240 mounted scouts, 16 cannons, and 47 machine guns. Under the pretext of fighting the rebels, the tsarist authorities aimed to physically destroy the Kyrgyz people. A ruthless mass extermination of the civilian population began, not to mention those who took up arms. Neither the elderly, nor women, nor children were spared; homes and entire ails were burned.

Overcome with panic and fear, fleeing from extermination, the Kyrgyz began to leave their homeland, fleeing to China. The people fled, leaving behind their settled places, cultivated fields, and the harvest grown through hard labor, taking only the most necessary belongings. This mass flight to China in the history of the people was called the “Great Turmoil.”

Many of those who escaped the punitive detachments of the tsarist troops perished on the way, unable to withstand the harsh trials.

Almost 200,000 Kyrgyz died during the uprising at the hands of the punitive forces, went missing, or died of hunger in China. The consequences of the uprising were especially tragic for the Kyrgyz of the Chuy Valley, Issyk-Kul, and Naryn.

Drowning the liberation struggle of the Kyrgyz people in blood, tsarism went even further. On October 15, 1916, a specially created commission decided to cleanse the territories of the Chuy Valley and Pre-Issyk-Kul from the Kyrgyz. Only Russian settlements were to remain on these lands. This decision was stamped by Governor-General A. N. Kuropatkin. The Kyrgyz, who had lived for centuries in the Chuy Valley and on Issyk-Kul, were deprived of the right to live on their native land. Thus, the plans of the predatory colonial policy of the Russian autocracy, which it had harbored for many years, were realized.

Only the overthrow of the Russian tsar in February 1917 and the October Revolution that took place in November 1917 saved the Kyrgyz from complete extermination.

The uprising of the Kyrgyz in 1916 for freedom was one of the most tragic pages in the history of the Kyrgyz people.

Kyrgyzstan as Part of Russia