GAZAVAT

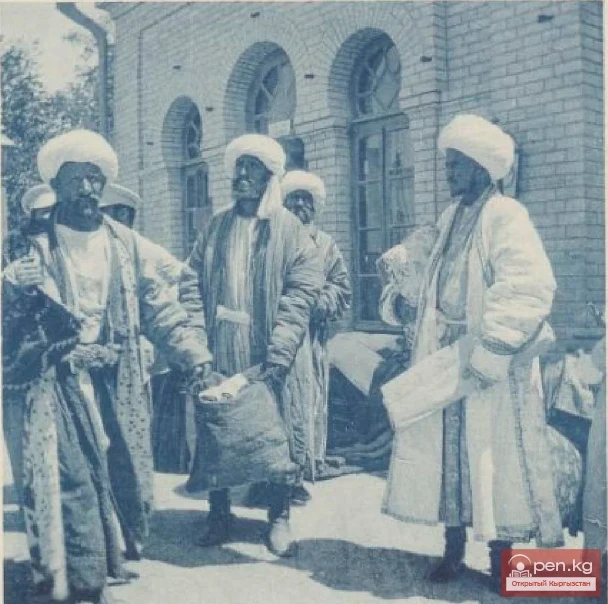

In early spring of 1898, alarming rumors began to spread in many villages of Fergana. It was said that a holy man, marked by the seal of Allah, had appeared in some settlement. And that this man denounces and prophesies, calls and predicts. He denounces the decline of morals and prophesies the end of the world if morals are not corrected. He calls for the punishment of the guilty. He predicts universal prosperity if those who corrupt Muslims are expelled and destroyed.

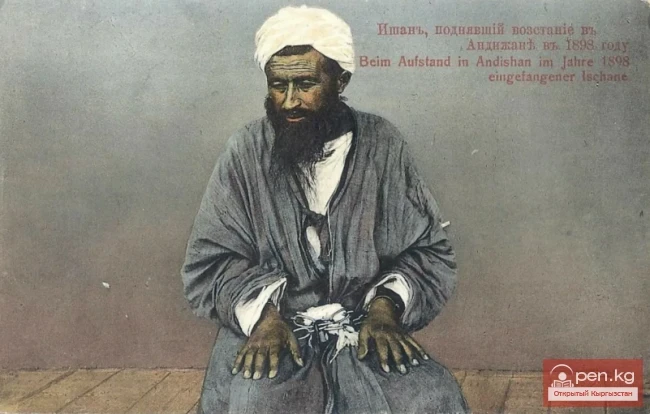

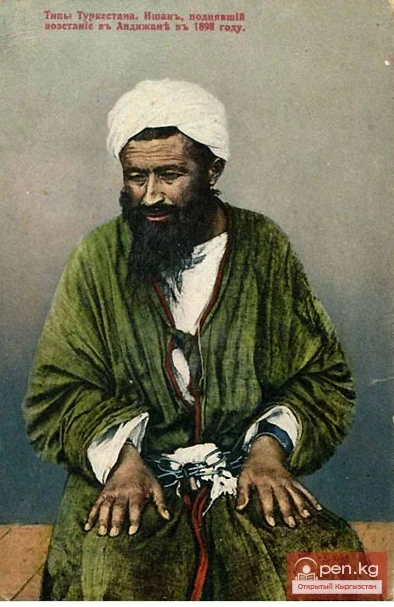

These rumors circulated particularly persistently in the Andijan, Namangan, and Osh districts. Finally, they gained specificity and tangibility. The holy man turned out to be Mahomed-Ali — Khalifa Muhammad-Sabir Uulu (shortened to Madali), an ishan from the village of Min-Tyube. He had another nickname: Dukchi-Ishan, meaning spinner (which indicates his profession).

He spoke at secret gatherings:

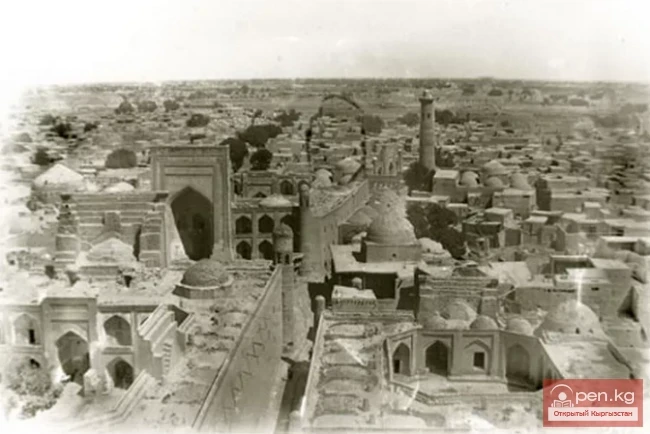

— Brothers! The time has come to free our land from the infidels! Look, the Russians are plowing our lands, the Russians are building houses in our ancient cities. On the sacred land of Muslims, they erect unclean places of worship and raise crosses on the domes! Their women walk with uncovered faces. They have brought with them the destruction of morals!

Their big and small leaders act here as if they are the masters. Their tax collectors shake us down for taxes: these taxes do not go into the treasury of the vicegerents of Allah, nor for the needs of the Muslim community, but flow out of our lands to unknown places! How long must we endure this?

Soon he had disciples — murids. They carried the words of “#mama” to the most remote villages. And these words fell on fertile ground.

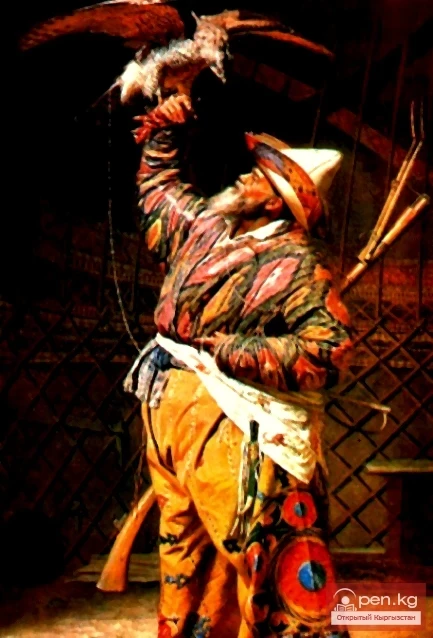

Who is this leader of the rebels? Madali-Ishan was born in 1853 in the village of Min-Tyube in the Margilan district to a poor family. His father, Muhammad-Sabir, owned only 5 tanaps of land and made spindles. Over time, Madali learned this craft as well. From a young age, he worked as a laborer and mud brick maker for the feudal lord — ishan Sultan-Khan Tyuri. Gradually, under the influence of the ishan, Madali became a murid, his follower, and then a halfiya — the vicegerent of the ishan. In 1882, after the death of ishan Sultan-Khan Tyuri, Madali became his successor. In 1887, he made a pilgrimage to Mecca and became the ishan of the Central Asian religious order of Muhammad Bogoetdin “Naqshbandiya.”

As a high spiritual figure, he received numerous offerings of animals, food, goods, and money. He had more than 40 murids and 30 attendants who supported the “glory” of their spiritual father in every way, spreading news of Madali's prophecies and “miracles.”

By the end of the 19th century, social relations in Central Asia in general (and in Southern Kyrgyzstan in particular) had developed as follows: local feudal lords and the tsarist administration, after the region's annexation to Russia, quickly found common ground and even partially merged into a single clan: bai and manaps, taking positions as volost administrators, aily elders, biys, and kazis, became tsarist officials themselves. Their interests were common: to live sweetly at the expense of the people.

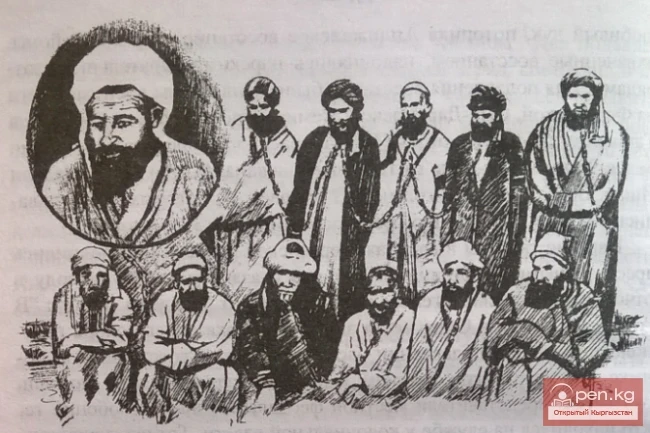

Ruthless exploitation, extortion and racketeering, arbitrariness and violence — all this inevitably led to a spontaneous uprising of the oppressed. Dukchi-Ishan and the clerical-feudal elite that supported him among the dissatisfied took advantage of the dire situation of the working people and directed their anger not at the true culprits, but generally against the “kafirs” under the banner of gazavat.

...The village of Tamchi-Bulak was located 20 versts from Osh, near the border of the Osh and Margilan districts.

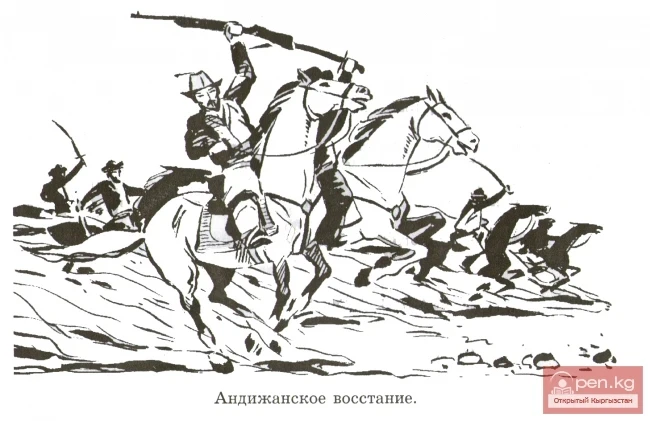

In the afternoon of May 17, 1898, about 300 people from the Naukat volost gathered in a small square here.

The people were armed with sticks, knives, homemade pikes, and even ketmens.

The excitement of the crowd was constantly supported by several leaders-murids of Dukchi-Ishan. A certain Omorbek Alimov led them. To be seen better, he climbed onto a cart and spoke passionately:

— Know, brothers, the people of the holy ishan will attack the Russians in Andijan and Margilan tonight. We will do the same here in Osh. If dogs attack a wolf from all sides, it’s the end for him. Let Azra'il and the most terrible shaytans take the souls of the kafirs to the underworld before dawn!

On that tragic night, from May 17 to 18, the rebels managed to attack the Russian garrison only in Andijan. The sticks of the rebels did not shoot. But the rifles of the Russians did not fire in vain. There were casualties on both sides.

Pointless casualties. For the uprising was doomed to failure from the very beginning.

The working masses, crushed by need and ravaged by extortions, fell for the agitation of the clerical-feudal elements, and they bore the main losses, being betrayed at the decisive moment by their “inspirers.”

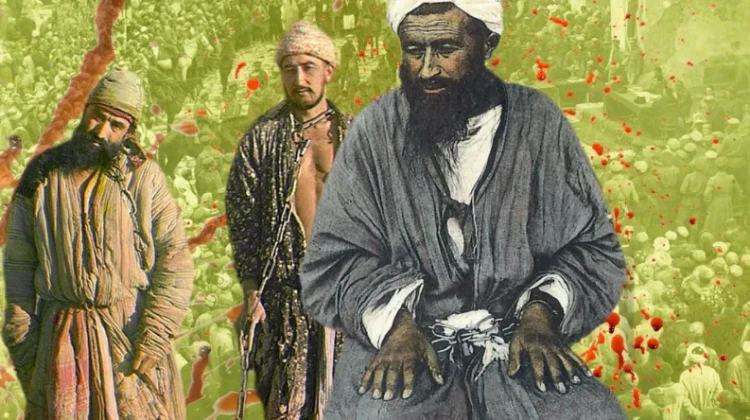

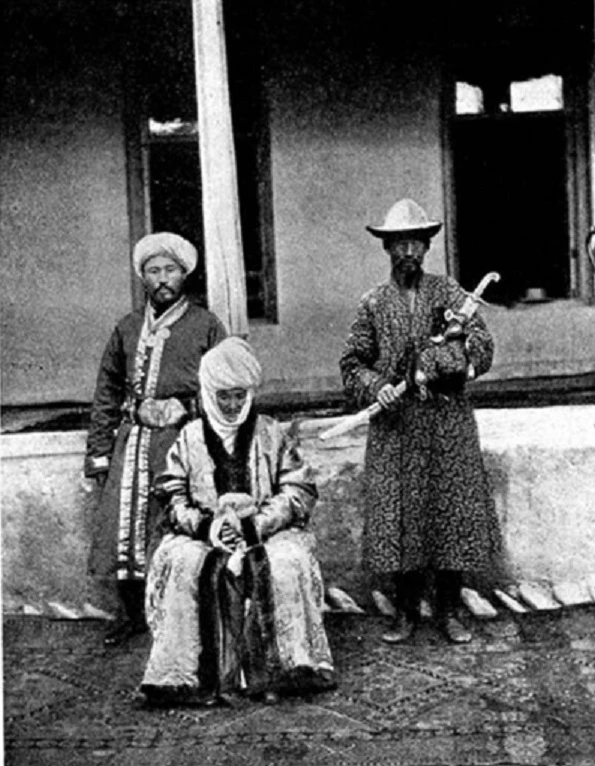

Thus, the uprising was suppressed. Dukchi-Ishan was hanged. His closest associates also suffered severe punishment. But the main blow fell on the “black bone,” on the bukara. The authorities arrested 257 Kyrgyz in this case, not counting representatives of other nationalities. By the decision of the military court in Osh, 106 people were sentenced to death. However, fearing a new uprising, their executions were replaced with many years of hard labor.

And the caravan of the condemned clanked with shackles. A long road... A terrible road to Siberia.

Among the doomed walked the akyn Toktogul Satylganov (1864—1933) from Ketmen-Tyube — the pride of the Kyrgyz people.

Toktogul's free-thinking, bold exposure of the exploiters provoked their burning hatred for the poet. The sons of the manap Ryskulbek, who had long harbored malice against the defiant singer, found the opportunity during this tumultuous time to deal with him. By their denunciation, Toktogul was falsely accused as an active participant in the Andijan uprising and sentenced to death by hanging. The execution was replaced with exile to seven years of hard labor in Siberia.

Upon returning from exile, Toktogul understood much. He scornfully rejected the rabid nationalism of the reactionary feudal-clerical circles. He warmly remembered and thanked in his songs his Russian friends — Semyon and Khariton, who organized his escape from hard labor, showed him the way, and helped with food and money.

Communication with Russian political prisoners helped Toktogul understand that it is not interethnic strife, but the struggle against all oppressors that should become the goal of the fighters for truth:

I see: next to me a Kazakh,

A Russian, a Kyrgyz, an Uzbek.

I see: they stand around,

Unfortunate, like me.

Each one is my brother and friend.

Prisoners, like me.

Toktogul became the banner of the Kyrgyz people in the struggle for a better future, their conscience.

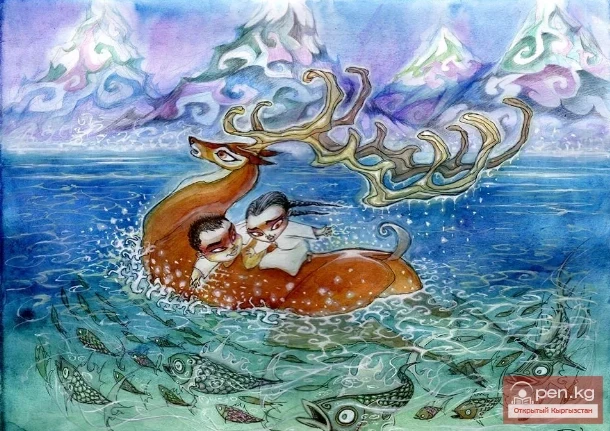

Myths and Legends