Popular Movements.

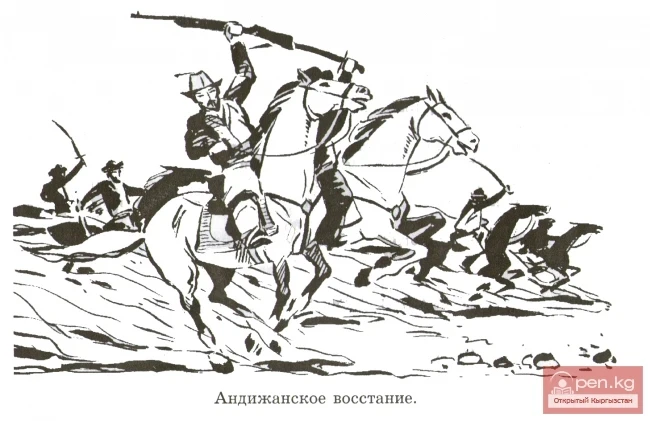

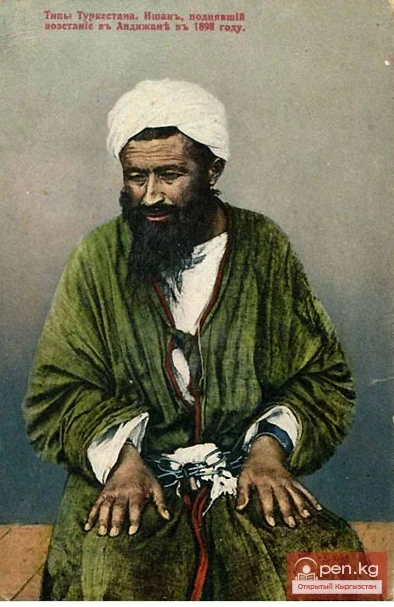

The Andijan Uprising is recorded in history as the largest popular movement of the late 19th century in the Turkestan region.

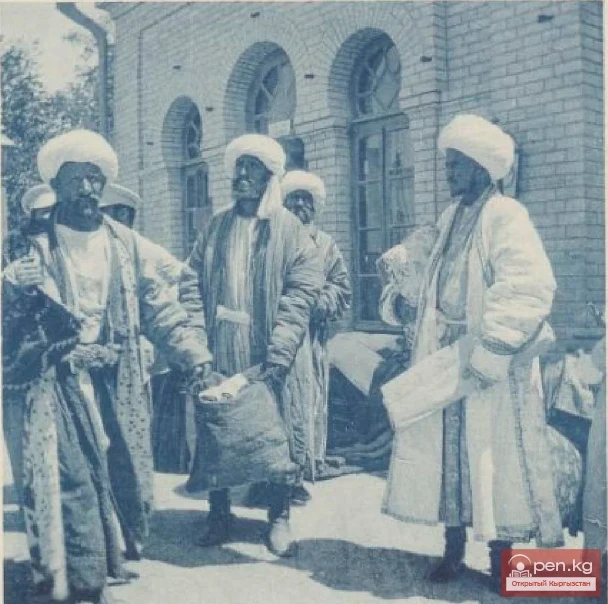

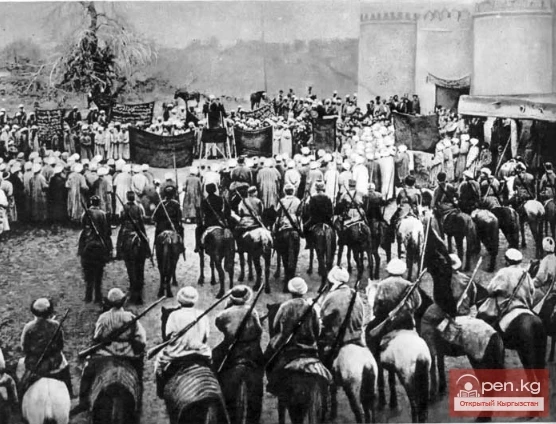

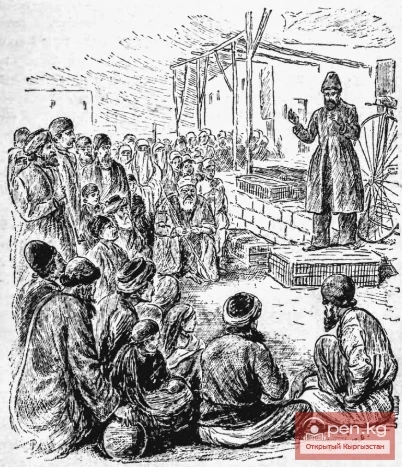

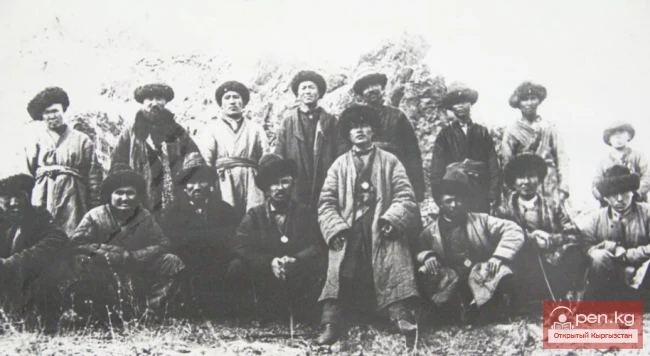

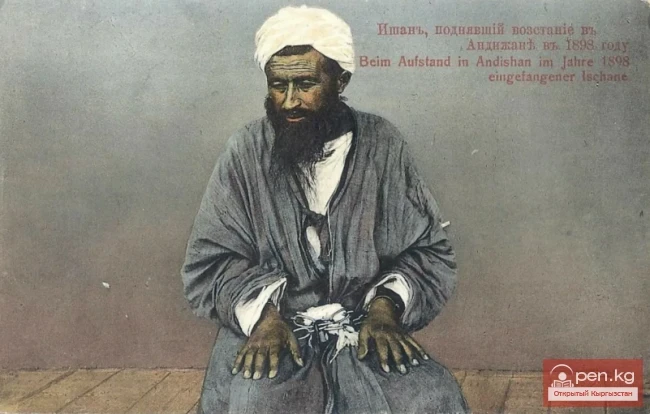

The main causes of the uprising were the colonial policies of tsarism, the intensification of social and national oppression, and the arbitrariness imposed by the Russian administration on the local population. Various social strata from several nations participated in the uprising, including Uzbeks, Kyrgyz, Tajiks, as well as representatives of other nationalities. The uprising erupted in May 1898 under Islamic slogans. On the evening of May 17, about 200 Kyrgyz and Uzbeks gathered in the village of Tajik (Min-Tyube). They were led by the village's ishan, Madali Dukchi, with the ideological leader being the Kyrgyz Ziyadin Maksym uulu (Ziyauddin Magzumi).

The rebels moved towards Andijan, cutting the telegraph wires connecting the city with the districts along the way. Residents of the villages of Kutchu, Kara-Korgon, and others joined them. Soon, the number of rebels reached 2,000. Around 3 a.m. on May 18, the insurgents entered Andijan and attacked the camp of the 20th Turkestan Line Battalion. In a fierce battle, over 20 tsarist soldiers and officers were killed. However, the rebels also suffered heavy losses. After crossing the Kara-Darya, they retreated to Hakim-Abad. In the village of Charbak, located 90 versts from Andijan, the leader of the rebels, Madali, was captured and hanged on June 12, 1898. This uprising was the first manifestation of the people's struggle against the colonial policy imposed in Turkestan (Kenenseriev, Avazov, 2002, pp. 161, 162).

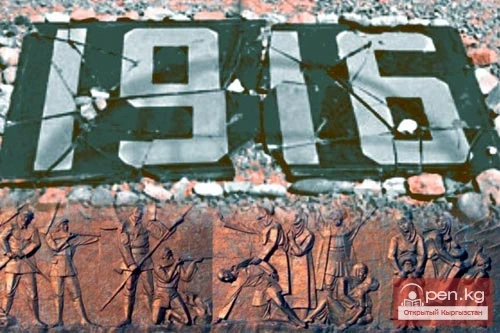

An even more powerful and bloody uprising occurred in 1916. One of its main causes was the mass resettlement of peasants from Russia and the allocation of land for them that was used by the local population. In 1916, Russians, who made up 6% of the population of Turkestan, were allocated 57.7% of the arable land. As for the local population, which constituted 94%, they were left with only 42.3% of the arable land (History of Kyrgyzstan, 1963).

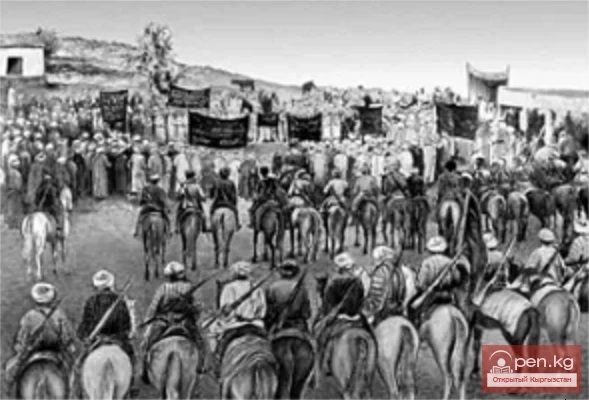

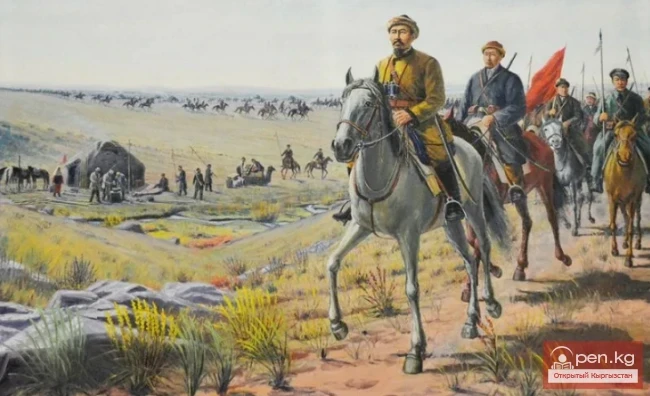

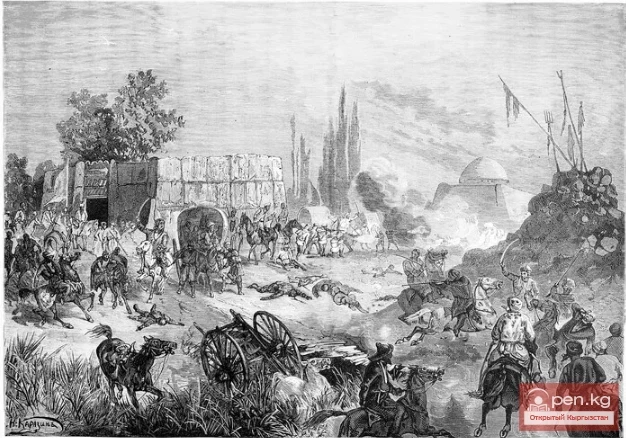

The First World War, which began in 1914 and involved Russia, placed a heavy burden on the shoulders of the common people. The tsar's decree of June 25, 1916, regarding the conscription of Turkestan peoples for military-defense work—men aged 19 to 43—provoked a wave of indignation (Uprising of 1916, 1960, p. 10; Usenbaev, 1967). The uprising, which began on July 4, 1916, in the city of Khojent in the Samarkand region, quickly spread to the Syrdarya and Fergana regions. The Kyrgyz actively participated in the July uprising. The uprising in the Namangan district was led by Talasbay Alybaev. The uprising in the Osh district began with a gathering at the foot of Sulayman Mountain of 10,000 discontented people. The Uzgen uprising was particularly intense. The protest movement spread in the valleys of Ketmen-Tube, Chat-kala, and Toguz-Toro.

The uprising in the northern region was characterized by particular sharpness and drama. Along with the Kyrgyz people, the majority of Kazakhs, Uighurs, and Dungans living in the district participated in the uprising. The Kemin Kyrgyz were among the first to take up armed struggle. The khan of the uprising was proclaimed to be the manap Mokush Shabdan uulu. By mid-August, the uprising had spread to 12 volosts of the Pishpek district, the regions of Issyk-Kul and Talas.

The Kyrgyz of Tian Shan also actively participated in the uprising. The rebels raised the bolusha (volost administrator) Kanat Ybyke uulu and proclaimed him khan. With 3,000 warriors armed with 30-40 Berdan rifles and matchlock guns, and mainly spears and axes, he descended through the Shamshinsky Pass into the Chuy Valley in early August. The rebels captured old Tokmok and besieged large Tokmok from August 13 to 22.

However, suffering heavy losses, the rebels could not hold their ground and were forced to retreat.

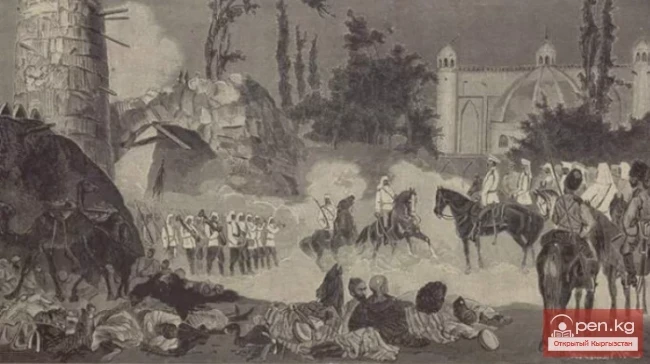

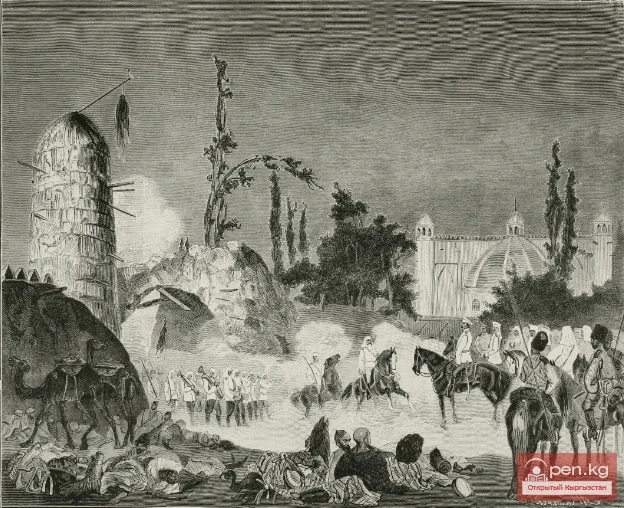

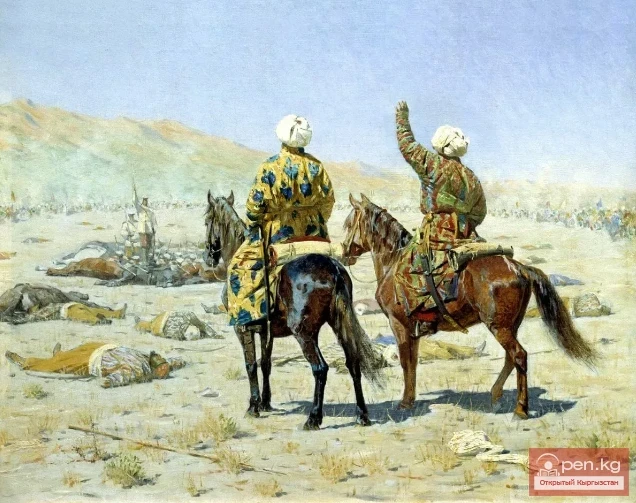

The uprising in the Issyk-Kul basin was marked by great tension. Starting on August 5, within just five days, it spread throughout the basin and reached Karkyra. The rebels ravaged resettlement villages, attacked peasants, burned houses and crops, and drove away livestock. The united forces of the Kyrgyz and Dungans besieged Karakol on August 11 (Sheishenakov, 2003, p. 96).

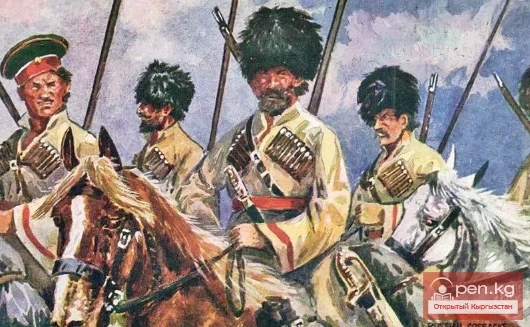

On July 17, 1916, martial law was declared in Turkestan, and by order of the military minister, 11 battalions and 3,300 Cossacks were sent to the district (Kydyrmyshev, 2006). At the end of August 1916, the last major battles between the rebels and Russian army units, Cossacks, and peasant militias occurred near Karakol. By September, with the exception of minor skirmishes with punitive detachments, the uprising was mostly suppressed.

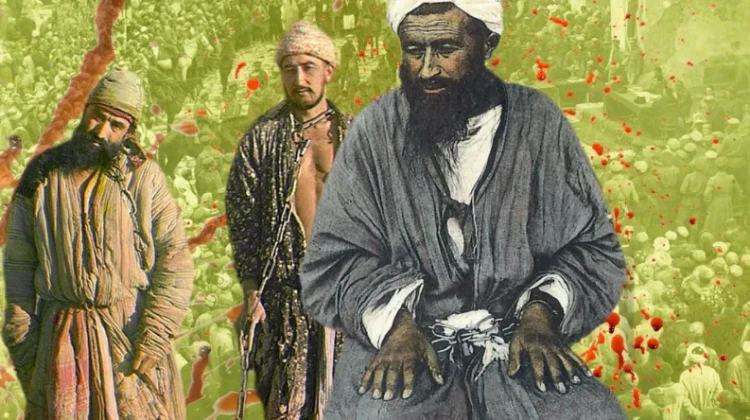

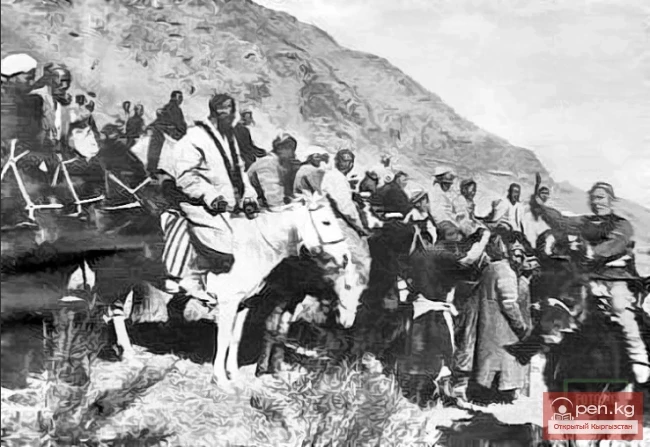

Fleeing from persecution, the Kyrgyz began a chaotic exodus into China at the end of September, abandoning their native lands, livestock, and property. The exodus (in popular memory known as "Urkun") occurred during the winter, and many who fled froze on snow-covered, icy passes, fell into ravines, or died of hunger. Many Kyrgyz later returned (according to Chinese data, the number of refugees reached 332,000), but the human losses were still significant. There is no consensus regarding the number of casualties from the 1916 uprising among the Kyrgyz. According to various estimates, the population lost between 40,000 and 140,000 people, including direct and indirect losses (from hunger, diseases, and accidents on the way and in China), as well as taking into account the coefficients of unrealized natural population growth.

The uprising was defeated and brutally suppressed. However, despite its failure, it had great historical significance. The tsarist government faced massive resistance from the local population, with representatives of various nationalities uniting in the struggle against the colonial system.

Industry of Kyrgyzstan within the Russian Empire