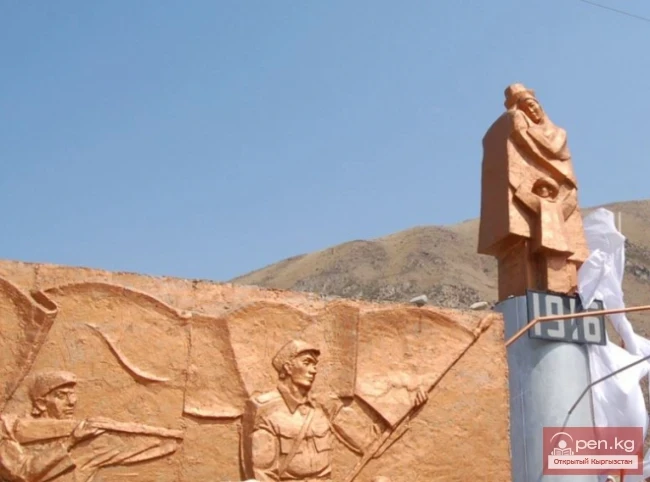

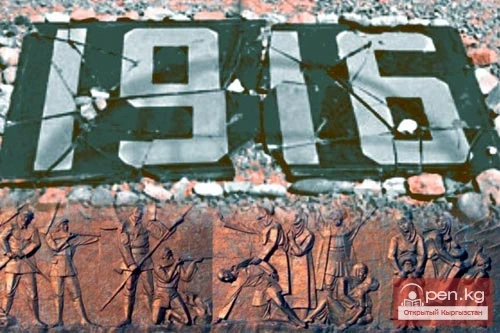

The Uprising of 1916 in Southern Kyrgyzstan

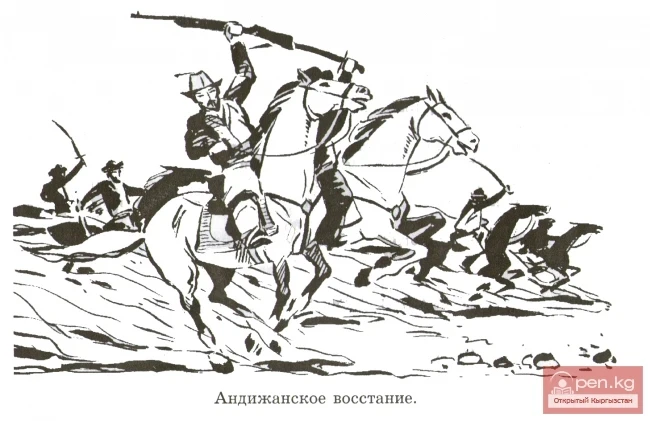

Deep dissatisfaction with the tsarist government and its anti-people foreign and domestic policies manifested itself, in particular, in spontaneous anti-war protests in Central Russia and the Central Asian outskirts of the country immediately after the first mobilizations of reserve soldiers. Among these was the protest on July 21-22, 1914, at the Andijan assembly point of peasants and townspeople called up to the army, who left behind unprotected families and unharvested crops. Among the active participants in the anti-war protests in Andijan, the authorities particularly noted those mobilized from the settlements in the southern part of Kyrgyzstan, called up in the Jalal-Abad and Kugart districts.

In August 1914 and autumn 1915, the miners of Sulyukta went on strike, even though this threatened them with being sent to the front. Discontent was also brewing among the workers of the Osh cotton gin, where Uzbeks and Kyrgyz predominantly worked.

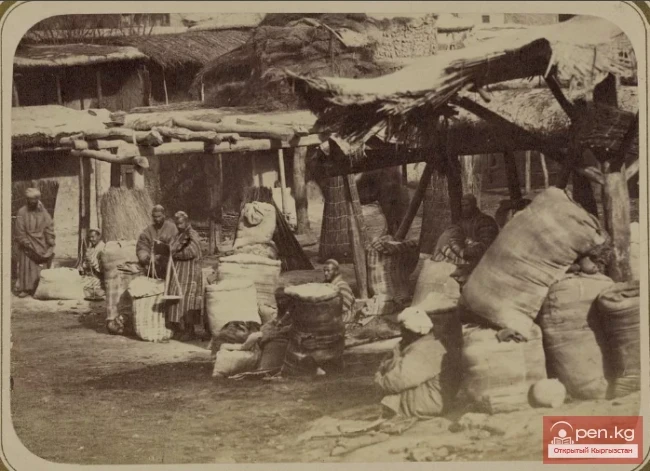

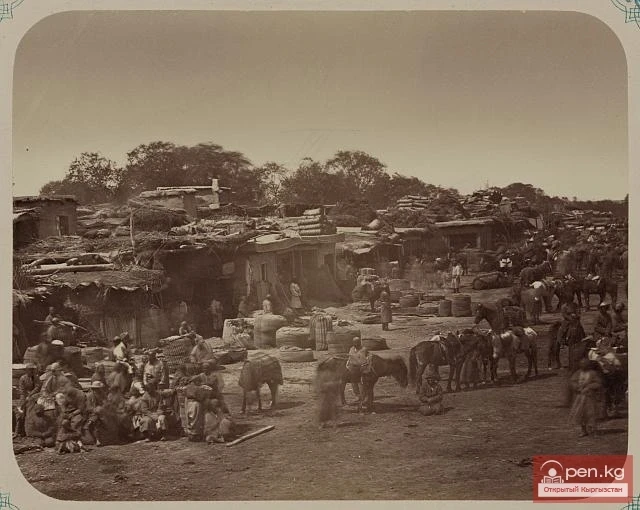

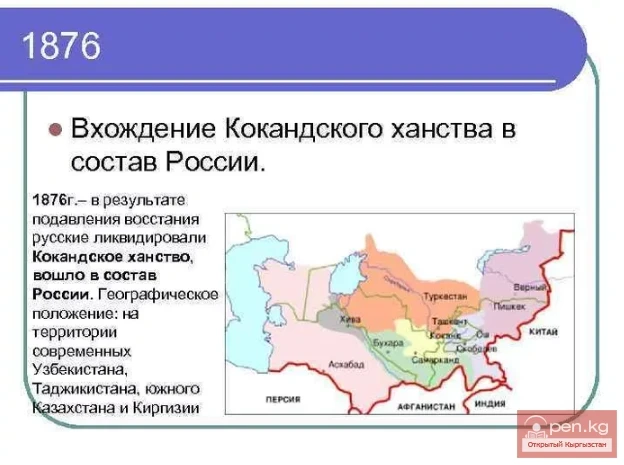

The situation of the working rural and urban population significantly worsened with each month of the war due to the growing economic devastation, monetary inflation, acute shortages, and rising prices for food and essential goods. Speculators profited immensely from this, as did traders, kulaks, and bai, while officials from the district and city authorities managing food supplies also benefited. The laboring indigenous population of Osh and the district, as well as the entire Turkestan region, especially suffered from the excessively heavy tax burden. Tsarism, which had always feared the introduction of military conscription for "non-Russians" (as the officials contemptuously referred to the indigenous population of Central Asia and Kazakhstan), instead introduced an additional military tax. This sharply worsened the economic condition of the peasants and urban artisans from the laboring part of the local Kyrgyz, Uzbek, and Tajik population in the Osh and neighboring districts in southern Kyrgyzstan. The military tax, introduced on January 1, 1915, for the subsequent three years, was levied at a rate of 21% in addition to state taxes, on urban real estate and industrial property, land state tax, state land tax, and tent tax. Burdened with debts to usurers and commission agents of textile firms, cotton growers from the Jalal-Abad volost of Andijan district and neighboring volosts of Osh and other districts expressed dissatisfaction with the low prices for cotton set by the authorities, which, as the Jalal-Abad residents wrote in a complaint to the Turkestan governor-general, did not even cover the costs of processing cotton fields. This was at a time when prices for iron and copper products, manufactured goods, tea, and other factory and plant products were skyrocketing. The communal livestock breeders of the Gulchinsky-Alaï region were also outraged by the low prices for cattle and horses, which were purchased from them by representatives of the military authorities.

The cup of popular patience overflowed with the tsar's decree of June 25, 1916, regarding the conscription of "natives" for military rear services and the subsequent instructions granting exemptions from it to representatives of the local administration, honorary citizens, clergy, students of madrasas, and other exploitative elements, who were either exempted from mobilization or could send a substitute.

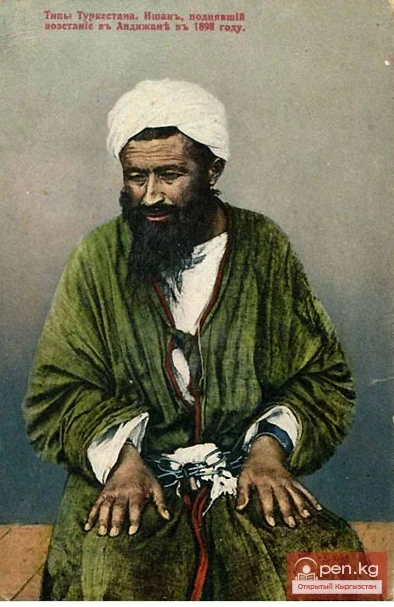

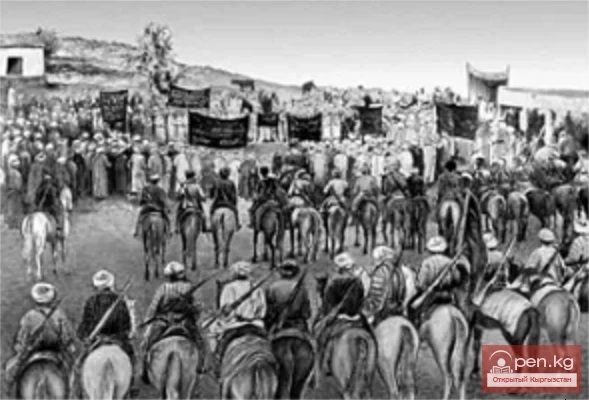

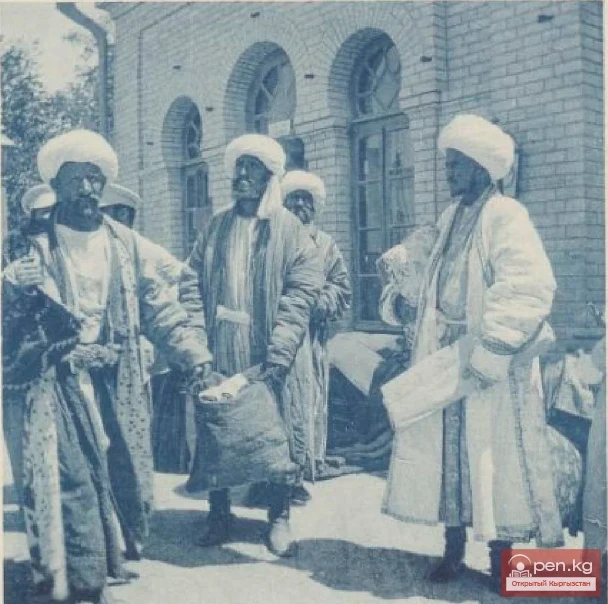

As recalled by an old resident of Osh, Rozakhun Akhmedaly, the local laborers — residents of his old city part, Kyrgyz kishlaks, and ails were especially outraged that "the rich and the bai did not include their sons in the lists (of those mobilized — ed.), and if the sons of the wealthy ended up on the list, they either paid off or bought a poor man, or forced a laborer to send his son instead of the master." The widespread discontent of the peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan with the intensification of national-colonial and social oppression erupted into a large-scale uprising in 1916. It began on July 4 in the city of Khojent in the Samarkand region, and by July 8 it had already spread to the Fergana region, all districts of which were engulfed in the flames of popular uprising by July 2. Moreover, in the Osh district, the authorities noted two major centers of unrest.

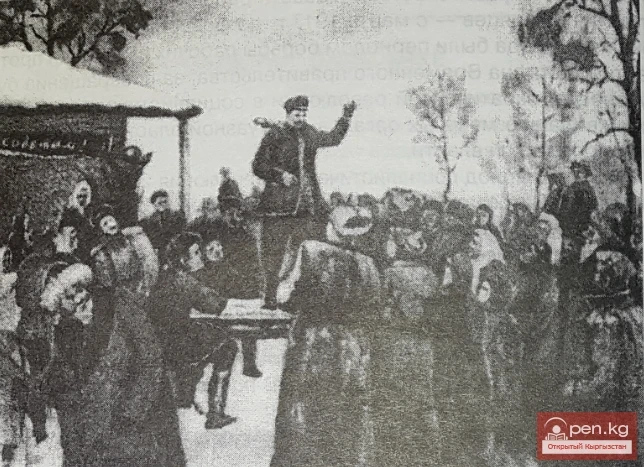

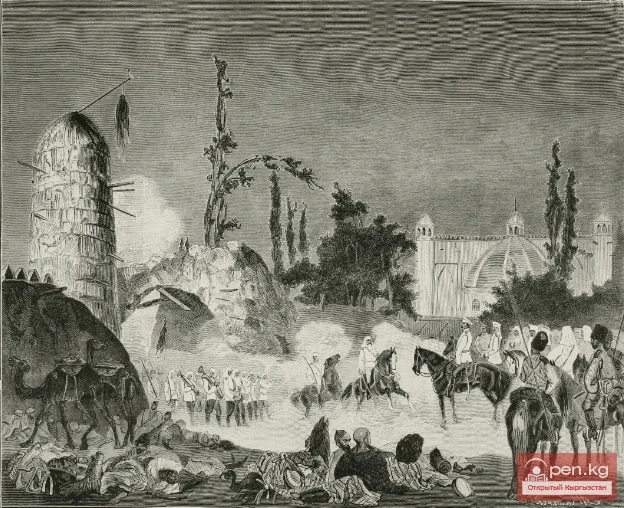

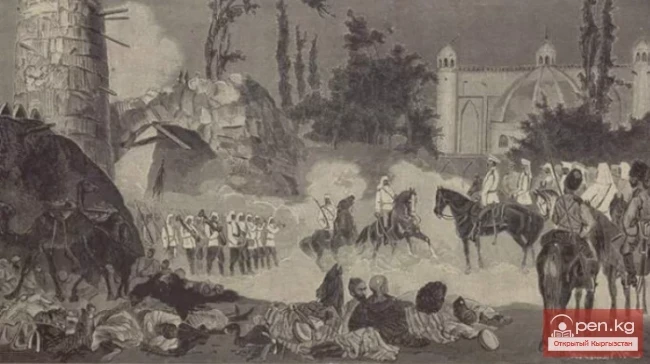

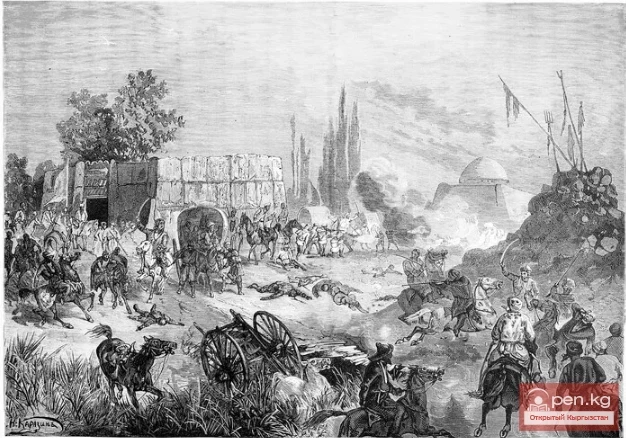

In early July, popular unrest also shook the district center — the city of Osh. Here, at the foot of Suleiman Mountain, a crowd of ten thousand residents from the old ("native") city, neighboring kishlaks, and ails gathered. The urban and rural poor — artisans, mardikers, and chai rikers protested angrily against the tsar's decree on the forced mobilization of the indigenous male population aged 19 to 43 for military rear services. In response to the "fatherly" appeal of the district chief, who arrived here accompanied by police officers and other officials, protest cries rang out: "We will not give our sons!", "We will not fight!". And when the aksakals, mullahs, and bai, along with the district and city officials, began to persuade those gathered and call for voluntary compliance with the decree of the ak-padysha ("white tsar"), stones, bricks, and sticks were thrown at the district chief and his entourage, forcing them to hastily seek refuge under the protection of soldiers' bayonets. However, the truthful words of the nameless popular agitators who spoke afterward found, as participants of this spontaneous gathering T. Rayimkhojaev and K. Mirzaev recalled, a lively response among the Uzbek and Kyrgyz poor. They said that the tsarist officials and their supporting volost, village, and aiyl elders, city aksakals, bai, and mullahs collectively oppress the local laboring people, whose friends are the Russian labor migrants. Only the punitive forces urgently summoned by the authorities dispersed the "rebels," arresting the most active among them.

Soon, mass unrest broke out in a number of kishlaks and ails in the district. The unrest that began on July 10-14 in the Bulak-Bashinsk volost was particularly acute. The rebellious peasants of the villages of Khojevot and Chokar on the former postal road from Osh to Andijan attacked the volost administrator, village elders, and fifty-men in groups of 50-200, demanding the issuance of lists. The rebels smashed the offices, homes, and property of the rural administration. They destroyed the found lists of those mobilized, as well as land and debt documents. In dealing with the despised tsarist servants from the feudal-bai milieu, they, however, as even tsarist authorities acknowledged, did not harm their families. Similarly, laboring Russian townspeople or peasant settlers were not harmed anywhere. All this indicates that the nationally-liberating character of the 1916 uprising in southern Kyrgyzstan took on a class anti-feudal direction in several areas.

Fearing just retribution from the laborers, representatives of the local ("native") administration fled in fear to Osh under the protection of their patrons — the tsarist authorities.

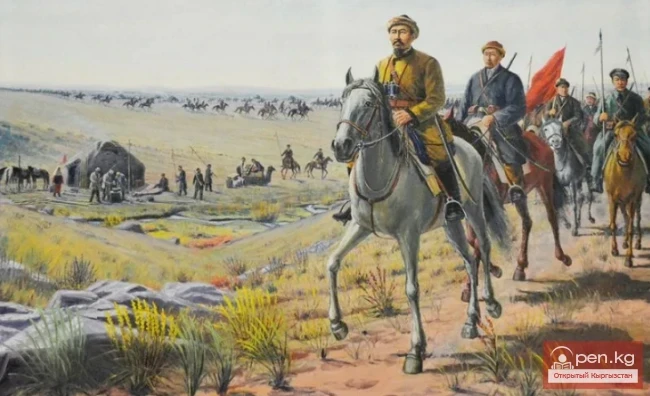

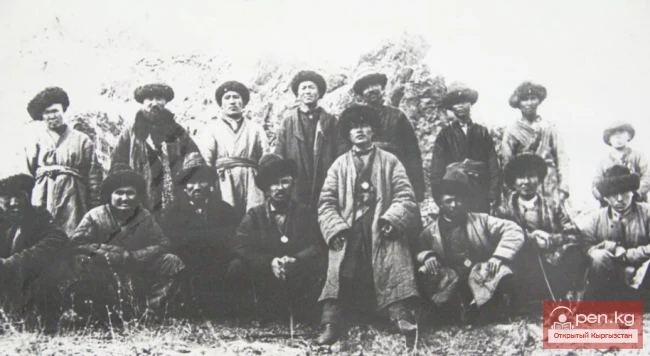

Following the initial unrest in Osh and the Bulak-Bashinsk volost, which were brutally suppressed by the authorities, uprisings of peasants occurred in the Yassin, Gulchin, Alai, Naukat, and Kurshab volosts of the Osh district, their sharp focus was directed not only against the tsarist colonizers but also against the exploitative feudal-bai elite. Bai and manaps, fearing popular wrath, sent trusted individuals to the district chief in Osh with requests to send soldiers and Cossacks. This was particularly true for the wealthy elite of the Uzgen and Uzgen volosts. Some of the rebels, usually armed with cold weapons, unable to withstand the clash with the superior forces of the punitive, were forced to hide in the inaccessible mountainous areas of Alai. Rumors, which greatly troubled the district authorities, suggested that somewhere in the vicinity of the Gulchin fortress, the rebels had a stockpile of firearms.

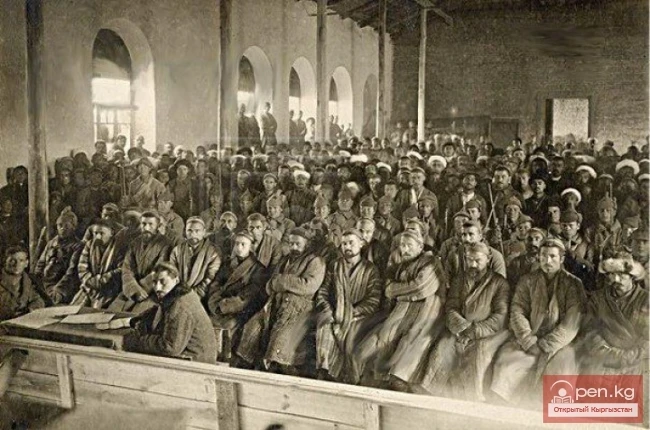

By autumn, the scattered centers of the uprising were suppressed throughout southern Kyrgyzstan, many of the rebels faced brutal reprisals, were arrested and tried, or, awaiting unjust trial, languished in the Osh prison. A heavy fate awaited the rebels who were taken for military rear service or forced to flee abroad.

As noted, the uprising of 1916 in southern Kyrgyzstan was characterized as a national-liberating, anti-colonial, and anti-war movement, and at certain moments, anti-feudal. Attempts by some reactionary elements of the feudal-bai circles and the Muslim clergy to give it an anti-Russian character clearly met with failure.