The Whirlwind of Revolutionary Events in Kyrgyzstan

The hastily assembled Soviet government clearly lacked people who were not just revolutionaries, but primarily capable of certain practical tasks. The power held on thanks to numerous promises, widespread confusion, and support from armed soldiers, sailors, workers, and internationalists. In Kyrgyzstan, however, the "new power," as usual, ended beyond the county centers and a few coal mines in the south. The revolutionary process here was only progressing with difficulty because Kyrgyzstan remained an appendage of Russia and, as part of a great power, was slowly but steadily being drawn into the whirlpool of revolutionary events, where the outcome of the struggle depended not on local forces, but on the strength and might of the revolutionary explosion at the epicenter, from which waves spread to the outskirts. If the revolution had failed in the center of the country, the outskirts would not have offered serious resistance to the counter-revolution. Let us provide a few examples taken from the "History of the Kyrgyz SSR."

After the October armed uprising, most of the Soviets in Kyrgyzstan remained in a position of non-recognition of the new power.

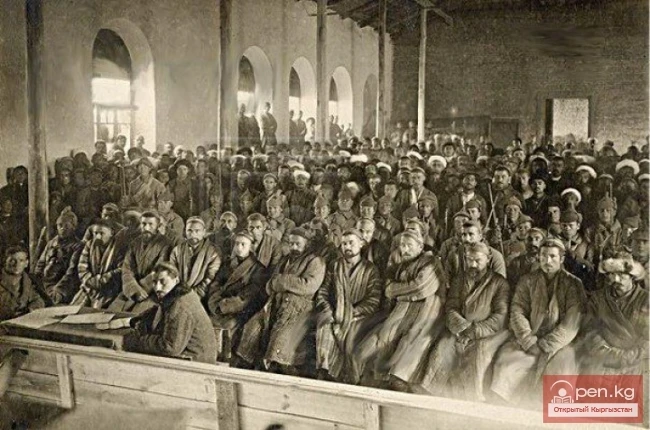

However, this was unimportant, as it did not lead them to play a greater role in the life of Turkestan society. The October coup intensified the chaos in the internal life of the vast region, where there was not a dual power, as in Petrograd and Moscow, but a multiplicity of powers, since almost every social organization claimed authority here. Among them were both the successors of the old power—the tsarist zemstvos and dumas, committees and commissariats of the Provisional Government—as well as trade unions, councils, parties, unions, and public formations that did not subordinate to each other and did not wish to submit to anyone. One after another, across the entire region, provinces, cities, counties, and volosts, numerous food, peasant, all-Kyrgyz, and other congresses took place, which alternately recognized and boycotted the central power in Petrograd, only to then, after some time, again polarize their position.

In Soviet historiography, this circumstance was deliberately overlooked and not analyzed, although it was regularly mentioned. There was a one-sided tendency to consider only the councils of deputies as the legitimate successor of power, as was the case in Petrograd and Moscow. The fact that in the struggle for power, Turkestan society, especially after the events of 1916, split along ethnonational lines into Europeans and Muslims, was completely ignored. For example, the first Soviet government of Turkestan was formed entirely of Europeans, of whom 8 were members of the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries and 7 were members of the Bolshevik party, which caused significant national discontent. This was an unprecedented and outrageous step by the new "people's government," considering that even under the tsarist regime and the Provisional Government, there were noticeable efforts on their part to expand the representation of indigenous peoples in the authorities and administration.

Even in the "counter-revolutionary Kokand government," which was baptized by the Bolsheviks and also claimed its legitimate right to full power in Turkestan, some ministerial portfolios were allocated to Europeans.

The Beginning of the Formation of "Red Terror"

Read also:

The Coup in Pishpek in March 1917

THE COUP IN PISHPEK The political coup that began in Pishpek was accompanied by a change of power,...

The Struggle of the Bolsheviks Against the SRs and Mensheviks for the Establishment of Soviet Power in Kyrgyzstan

The Soviets became local authorities that primarily influenced representatives of the European...

Pishpek - the Center of Revolutionary Struggle in the Chui Valley

The Beginning of the Recognition of Soviet Power in Pishpek and the District In the summer,...

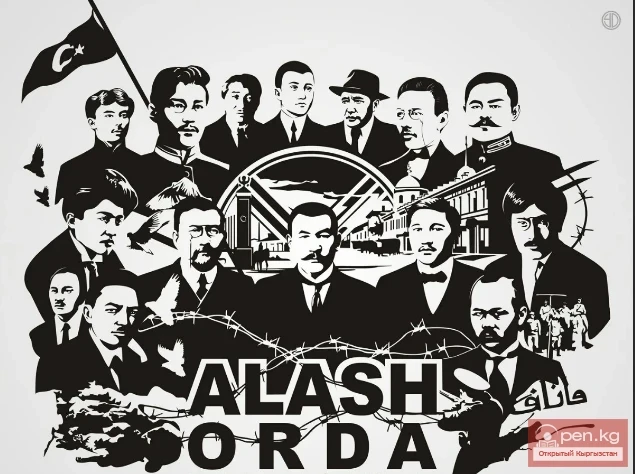

Legalization of the "Alash" Party after the Overthrow of the Tsarist Regime

The Alash Party and its leaders were accused of betraying the interests of their people in 1916,...

The Parties "Alash," "Turan," "Shuro-Islamiya," and Others in Kyrgyzstan in the Early 20th Century

Struggle for Power Among Individual Exploitative Groups With the overthrow of Tsarism (according...

Osh. City Management

Police Administration in the City City management particularly vividly reflects the discriminatory...

Osh. Events in Southern Kyrgyzstan in February 1917

February Bourgeois-Democratic Revolution of 1917 in Osh. The overthrow of the tsarist autocracy on...

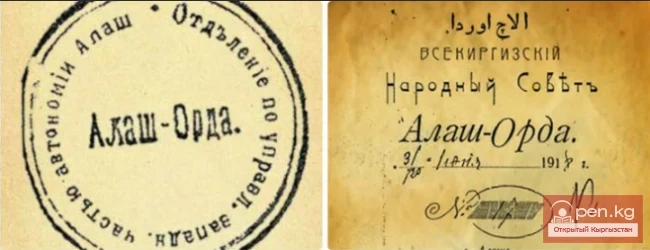

Establishment of the Pishpek Branch of the Kazakh-Kyrgyz Party "Alash-Orda"

Soon A. Sydykov resigned, as the Provisional Government disappointed the expectations of the...

Administration in Kyrgyzstan within the USSR (1917-1991)

The establishment of Soviet power and statehood in Kyrgyzstan began after the October Revolution...

Establishment of Military Administration in Fergana Region

Military-Police Administration As we can see, the ancient city at the beginning of Russian rule...

The Overthrow of Autocracy and the Establishment of Soviet Power in Kyrgyzstan

The Tsar is Overthrown. The life of the people did not improve. In early 1917, the news spread...

The Penetration of Revolutionary Ideas into the Masses of Turkestan

Propaganda of proletarian ideas in Turkestan by political exiles Political exiles, especially...

Rebellion Against the Colonial Foundations of Tsarist Autocracy

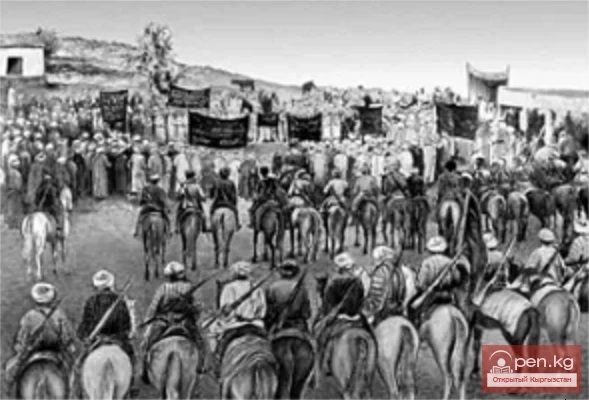

National Liberation Uprising The uprising we are interested in took on a religious guise; however,...

Outcomes of Popular Movements in Central Asia in the 19th Century

The uprisings and revolts that took place in Kyrgyzstan, as well as in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and...

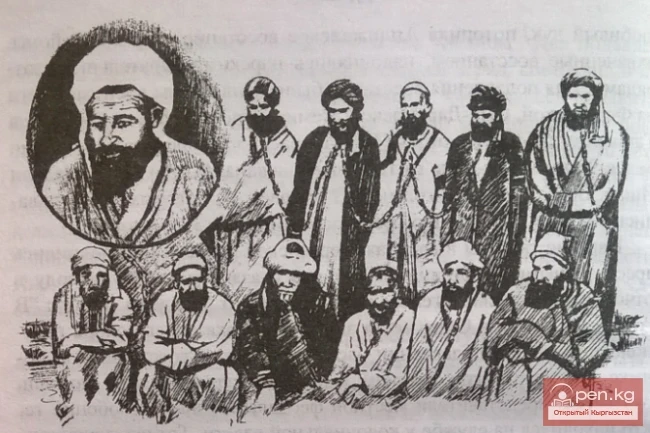

The Execution of Madali Ishan and His Associates

Madali Ishan and other participants of the uprising before execution Colonial Authority Against...

Colonial Policy of Tsarism towards the Kyrgyz

Administration. Russia introduced its own system of administrative governance in Kyrgyzstan....

Strengthening the New State. The Constitution of Kyrgyzstan

Adoption of the New Constitution With the acquisition of independence, the renewal of the state...

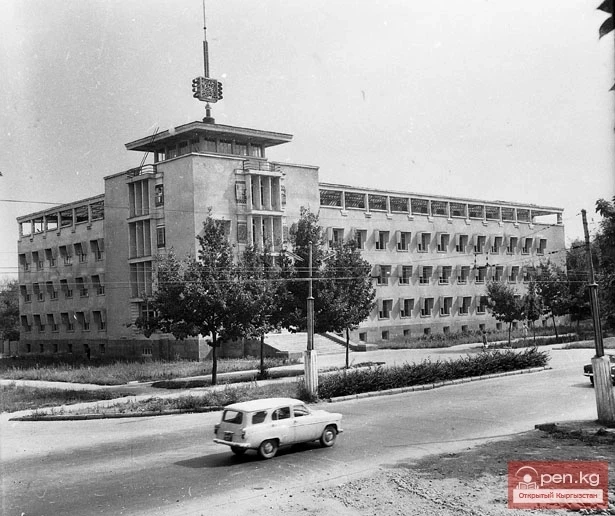

Development of Science in Kyrgyzstan during the Soviet Period

1960-1966. Academy of Sciences of the Kyrgyz SSR Certain successes were achieved in science. In...

My Dear (The Mayor)

Zharkynaiym. In the political life of the Kokand Khanate, an interesting role was played by the...

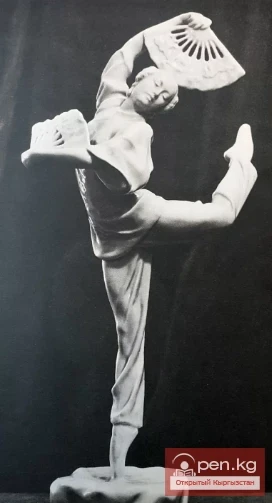

B. Beishenaliev in the ballet "Red Poppy" by R. M. Glière

B. Beishenalieva as Tao Hoa For a long time, B. Beishenalieva had to perform in ballet productions...

Strengthening the Administrative-Command System of Kyrgyzstan

Establishment of Autocracy. The Soviet power had many enemies—both external and internal. They...

Kyrgyzstan in the 1920s. Introduction. Part 1

Kyrgyzstan in the 1920s. Introduction With the establishment of Soviet power, a political culture...

Esin-Buka and Other Emirs

Esan-Buka Esan-Buka, his ulusbek (Seiid Ali), and his court continued to pursue the supporters of...

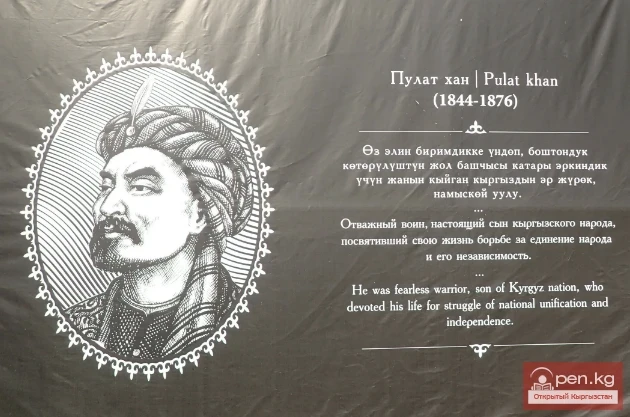

Support for the Rebels and Participation of the Local Population in the Uprising

Support for the Rebels by the Local Population The uprising of 1873-1876 began and unfolded as an...

Kyrgyzstan on the Path to an Open Society

Kyrgyzstan today is a sovereign independent state building an open society. An open society is one...

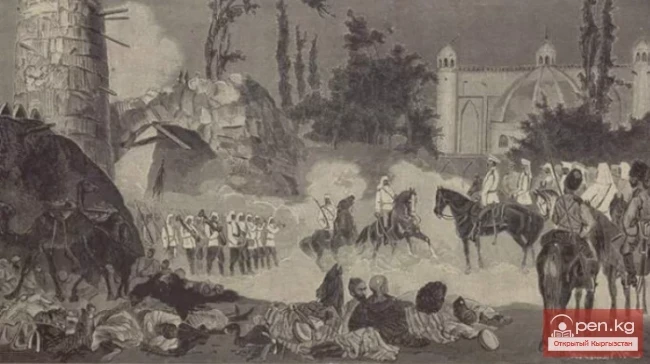

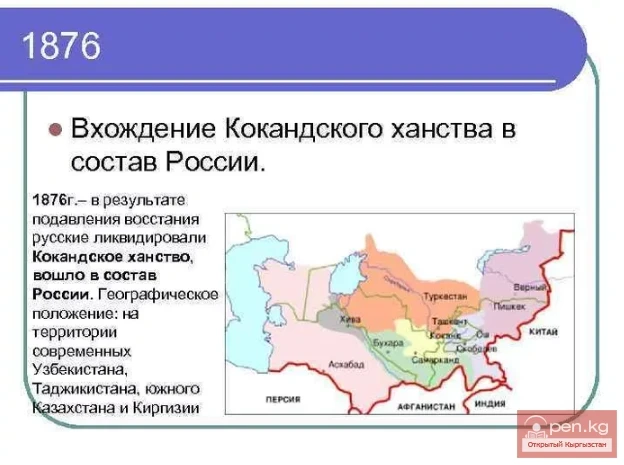

Preconditions for the Liquidation of the Kokand Khanate

Forced Liquidation of the Kokand Khanate The tsarism, the patron of the Kokand khans, failed to...

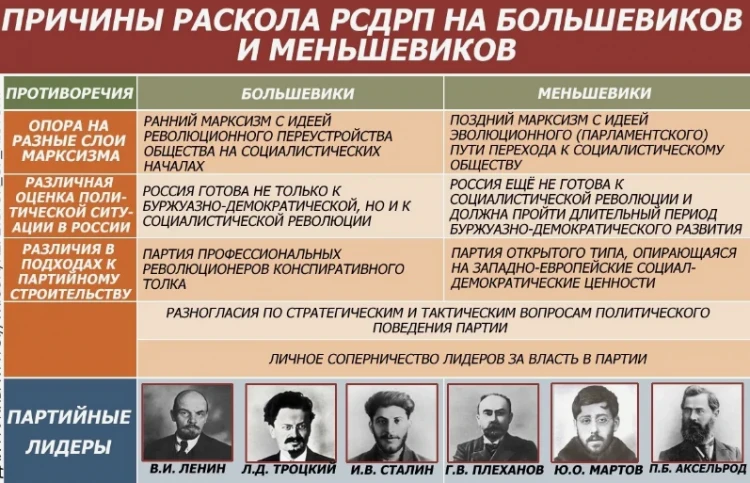

Formation of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party (SRs)

The Socialist-Revolutionary Party (SRs) was formed in Russia in 1902 and made a loud statement...

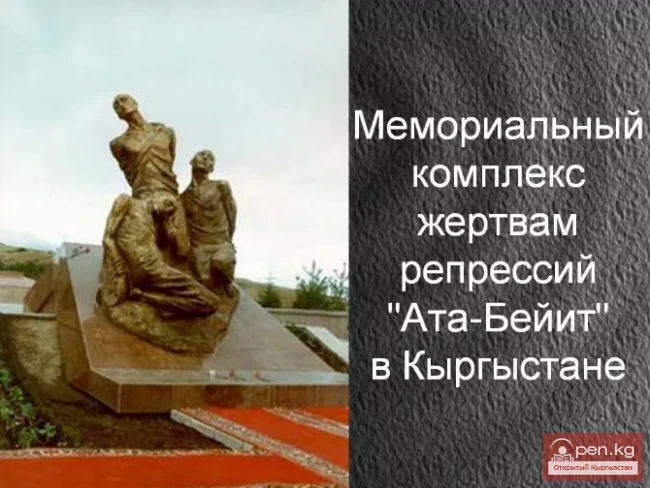

The Thirty-Seventh Year in Kyrgyzstan

1937... For almost everyone alive today, this period in our history evokes a heavy sense of...

New Authorities - New Money

After the victory of the February bourgeois-democratic revolution, power in Russia passed into the...

Osh. Revolutionary Events of 1905-1907.

The revolutionary protests of workers, townspeople, and peasants in southern Kyrgyzstan in...

Privileged Kyrgyz Estates Between the Past and the Future

“Who is not with us is against us” The traditional way of life of the Kyrgyz tribal society began...

Manapism and Russian Reforms

Bureaucratic Apparatus of Management among Southern Kyrgyz Tribes The social and property...

Political Exiles in Turkestan

Turkestan - A Place of Exile for Political Prisoners The penetration and spread of revolutionary...

Program of the Alash Party

A. Bukeykhanov, M. Tynyshpayev, Zh. Seydalin, M. Dulatov, and others played a significant role in...

The Role of the Individual in History

"When creative people cease to appear, revolution is inevitable." The concept of A....

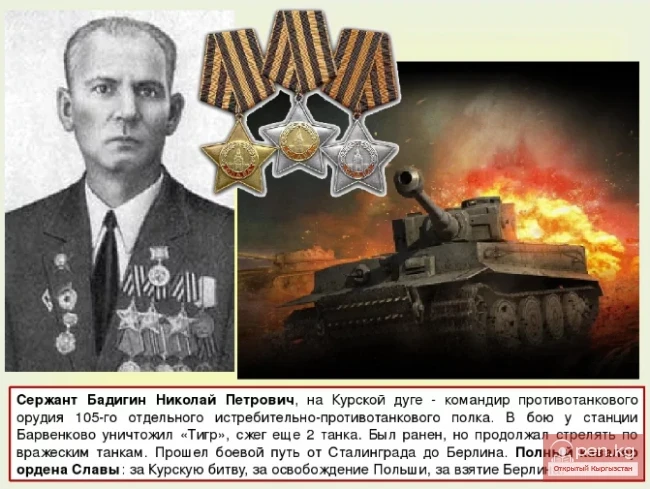

Deserved People of the City of Osh

People of Osh Who Earned Respect In the city of Osh, there have been a number of honorary and...

Formation and Development of the National Statehood of Kyrgyzstan

National Policy of Soviet Power Among the main points of the Bolshevik party program, led by V. I....

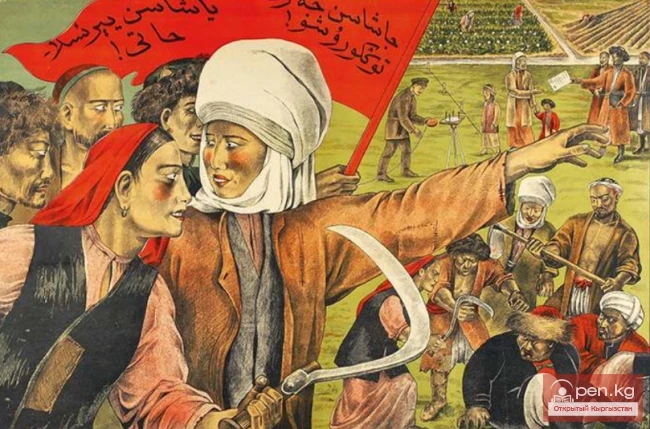

Socialist Transformations in the Economy of Kyrgyzstan

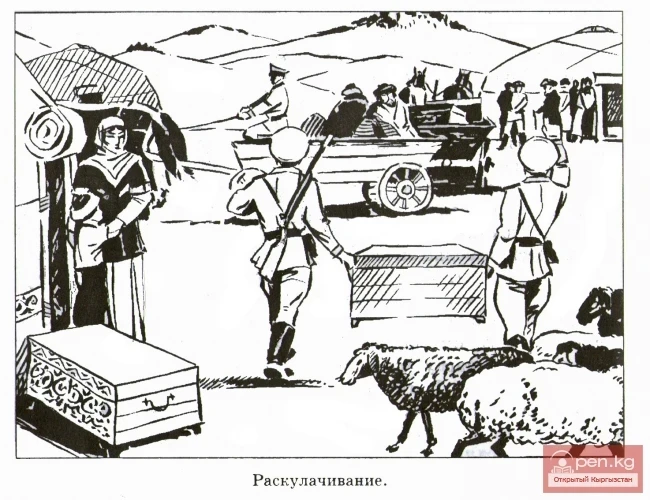

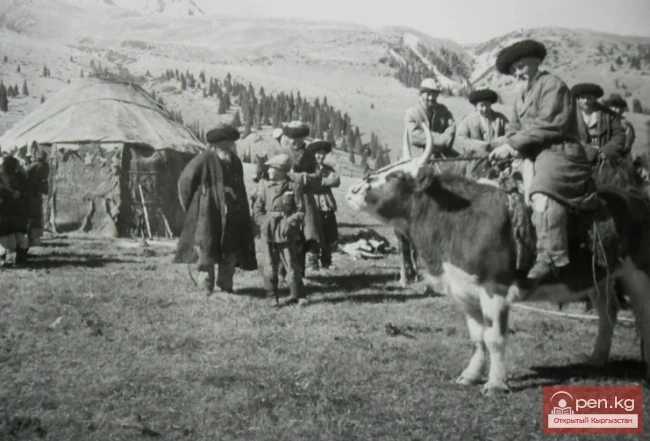

Land Redistribution. One of the main issues that the revolution had to address was the question of...

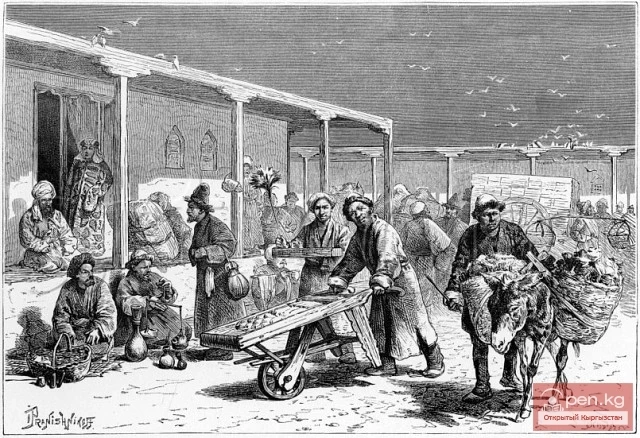

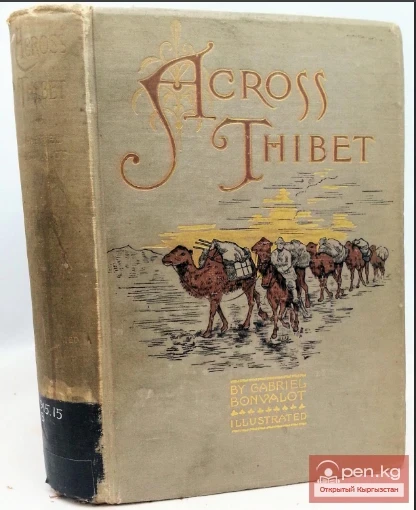

Asia Through the Eyes of the Traveler G. Bonvalot

ALIEN FROM ANOTHER WORLD However, the Russian reader was informed about some of the...

Popular Uprisings Involving Kyrgyz People

CLUSTERS OF WRATH For a researcher, it is not easy to classify the protests against the...

Administrative System of Governance in Turkestan

Administrative Policy. The organization of governance in Turkestan, including the Kyrgyz lands,...

The Foreign Policy of the Kyrgyz during the Soviet Period

The foreign policy of the Kyrgyz SSR was built in accordance with the foreign policy course of the...

The Path of Nomadism - Pasture Committees in Kyrgyzstan

The film tells about the life and work of shepherds in the highlands of Kyrgyzstan and how new...

Results of the Uprising Led by Pulat Khan in 1873 - 1876

The clan leaders of many southern Kyrgyz tribes, not connected with the court clique, began to...

Establishment of Kyrgyz National Statehood

The coup of August 19, 1991. The course of deepening democratic changes in the USSR, conducted by...

Kyrgyz Special Services Continue the Fight Against the Opposition

The investigation into the opposition conspiracy to overthrow the government continues in...

The First Attempt at Political Discrediting of A. Sydykov and the Left Socialist Revolutionary Movement in Turkestan

One episode from the life of A. Sydykov is associated with his membership in the Left...

Population of Kyrgyzstan as of January 1, 2013

Population of Kyrgyzstan Thanks to the fundamental changes that occurred in Kyrgyzstan after the...