Land Redistribution.

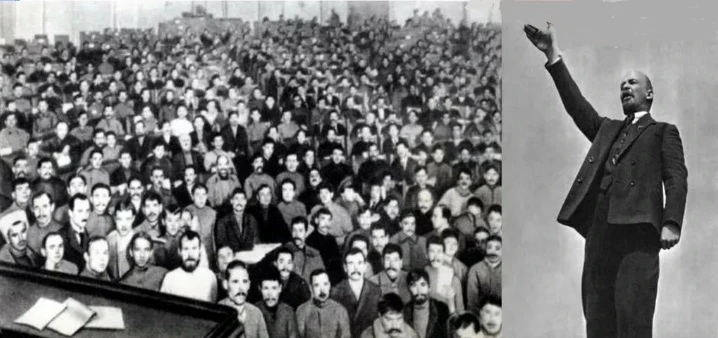

One of the main issues that the revolution had to address was the question of land distribution to the peasants, who made up the majority of the population in Russia and its outskirts. To win the support of the peasantry, the Soviet government adopted the Decree on Land, which outlined the main directions of the new government's agrarian policy. According to this decree, all imperial, landlord, church, and monastery lands were confiscated along with their inventory and buildings and transferred to peasant committees and councils for distribution among the peasants. Peasants were granted land, and their debts were canceled. To help them establish their own farms, peasants were provided with financial and material-technical assistance. These measures received widespread approval and support from the peasantry.

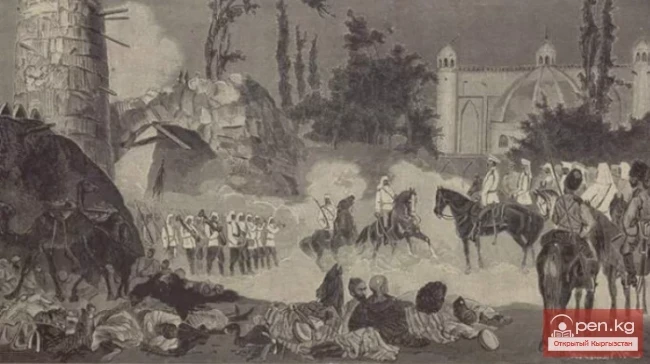

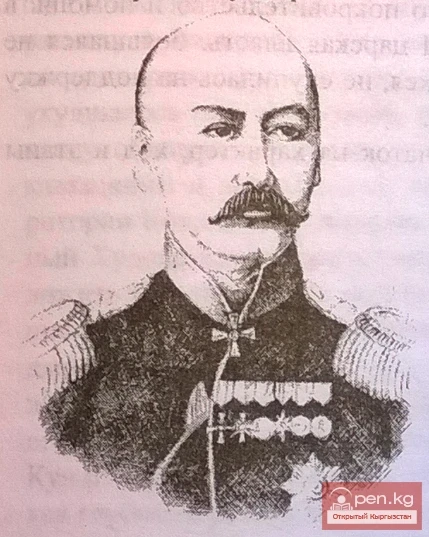

The land question in Kyrgyzstan was particularly acute because, under the tsarist regime, all the best lands had been given away or seized by settlers coming from Russia. Without the redistribution of these lands, the Kyrgyz could have been left completely landless.

The state confiscated lands from large landowners. In 1918, property was confiscated from the Issyk-Kul Monastery in the Przhevalsk district, and its lands were distributed among landless peasants, orphanages, and an agricultural school. Lands that had been seized by tsarist officials were also confiscated and distributed among the peasants.

Land-Water Reform. To eliminate inequality in the use of land and water between Kyrgyz peasants and Russian settlers, the Soviet government conducted land-water reform in 1921-1922.

Under this reform, excess land from Russian kulaks and Kyrgyz bai and manap was confiscated and transferred to landless peasants. Russian settlements, hamlets, and farms that hindered the free use of land and water by Kyrgyz peasants and the grazing of livestock were to be liquidated. The reform was primarily carried out in areas densely populated by Russian settlers.

As a result of the land-water reform, most Kyrgyz peasants received land. Their expectations and hopes were fulfilled.

However, mistakes were made during the reform. The amount of arable land in Kyrgyzstan was not taken into account, and there was no record of landless or land-poor peasants. Settlements of Russian settlers that had been illegally built on lands seized from the Kyrgyz were liquidated, and these places were settled by Kyrgyz people. This led to a deterioration in the situation of the Russian poor and an increase in their discontent.

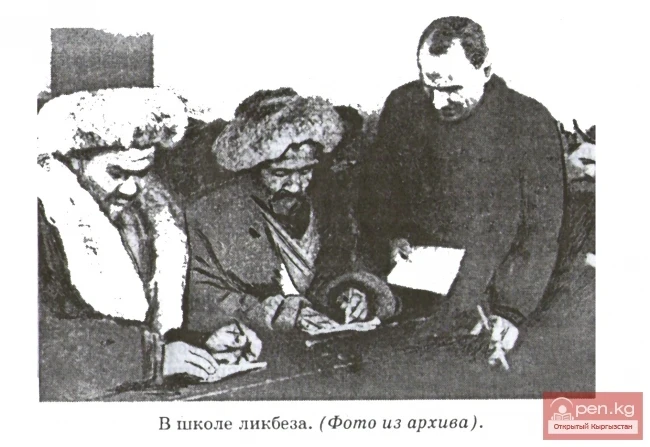

Transition to Sedentarism. In 1923-1926, the second stage of the land-water reform began. The Soviet government aimed to unite fragmented private peasant farms into collective ones with public ownership. But for this, it was first necessary to transition the nomadic Kyrgyz to settled farming.

To encourage people and speed up the transition to settled farming, they were provided with agricultural tools for land cultivation and seeds for planting. In addition, they were exempted from paying taxes for five years. Settling peasants were given free access to forests for establishing their farms and building housing.

In 1927-1928, the land-water reform was carried out in southern Kyrgyzstan. Thousands of peasants received land.

Thus, gradually, the Kyrgyz, who had led a nomadic lifestyle for centuries, transitioned to a new type of farming. The question of consolidating private farms now arose.

The first collective associations appeared in the Chui Valley — the farm “Alamudun” and at Issyk-Kul — “Toktoyan.” The economic results of their activities were higher compared to private farms. Members of these farms began to earn more income and live better. Their successes positively influenced other peasants. The simplest forms of cooperation began to emerge — communes and artels.

Having received land, peasants worked it with great dedication, increasing the sown areas and improving soil cultivation. The results were quick to show: the yield of peasant allotments increased, and the number of livestock grew. Agriculture began to rise.

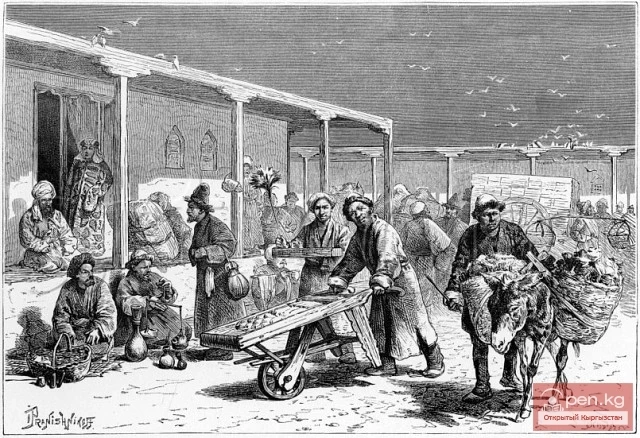

Industry. By the time Soviet power was established, the industrial development of Kyrgyzstan was very weak: there were only a few cotton ginning, leather, and food enterprises. There were also very few workers.

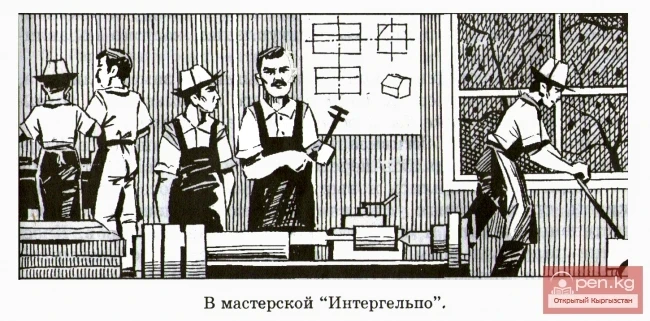

In 1925, workers arrived from Czechoslovakia to assist in socialist construction, founding the cooperative “Intergelpo” (“Mutual Aid”). In a relatively short time, the collective, which included representatives of 14 nationalities, built a brick factory, sawmill, leather factory, power station, wool factory, and several mechanized workshops, which significantly impacted the economic development of the country.

In Kyrgyzstan, small enterprises began to be established and gain strength. However, it continued to remain an agrarian country, as agriculture and animal husbandry formed the basis of its national economy.

To implement socialist transformations in the economy, it was necessary to radically change the situation in industry. The Soviet government allocated significant funds to Kyrgyzstan. This allowed for the commissioning of large factories and plants and the beginning of oil field development. Coal production increased. Heavy industry, the production of non-ferrous metals, construction materials, and machine engineering gained strength, and electricity generation increased. If in 1926, industry accounted for only 2 percent of the total production in the republic, by 1940 it had risen to 50 percent. This was a significant achievement for the economy of Kyrgyzstan.

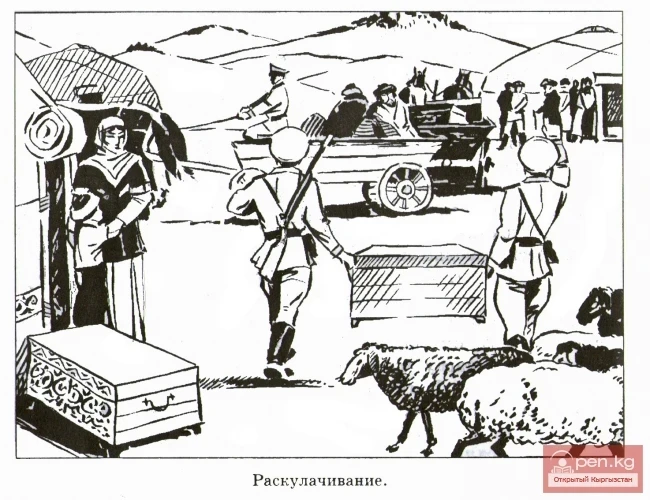

Collectivization. The overwhelming majority of peasants who received land operated individual farms. However, there were already collective farms. Thus, peasants could choose between two types of farming, the one that was more beneficial for them. However, this did not happen. The Soviet government began a policy of forced collectivization of peasants — uniting them into collective farms. In 1929, Stalin proclaimed a course for “complete collectivization” of agriculture, even setting deadlines for its implementation. The entire power of the state administrative-command system was dedicated to fulfilling this task.

Local party and Soviet bodies in Kyrgyzstan sought to report their successes as quickly as possible. Competition began for the early completion of collectivization.

However, in reality, not all peasants were ready to unite into collective farms. Initially, the poorest peasants joined them. The more prosperous did not want to join the collective farm and give their hard-earned property and livestock for common use. Such peasants were declared kulaks, stripped of their voting rights, and expelled from Kyrgyzstan. There were cases when collective farms created by force collapsed a few days later. To avoid giving their own livestock to the collective farm, peasants sold or slaughtered it. Others migrated to China, taking their livestock with them. As a result, the livestock population in Kyrgyzstan significantly decreased. In some places, peasants resisted forced collectivization with arms in hand. Their uprisings were brutally suppressed.

But the pace of collectivization did not slow down; on the contrary, it accelerated. By 1940, all peasant farms in Kyrgyzstan were united into collective farms.

The collectivization of agriculture in Kyrgyzstan was accompanied by the transition of the nomadic part of the Kyrgyz to a settled lifestyle. New villages appeared. The settled way of life, work under new conditions in collective farms gradually changed the social consciousness of the Kyrgyz. Peasants gained the opportunity to engage with the achievements of culture and civilization. An economic upturn in agriculture began.

The agrarian reform was supported by large-scale activities to create a system of artificial irrigation, which was very important for agriculture. In every region, small and large irrigation networks — ditches and canals — were being constructed. In 1934, the Chumyshev Dam with a reservoir was built. By 1939, the total area of irrigated land reached 732 thousand hectares. In March 1940, a decision was made to construct the Orto-Tokoy Reservoir and the Big Chui Canal. The construction of these facilities, which began in 1941, involved large masses of the local population, who demonstrated true labor heroism.