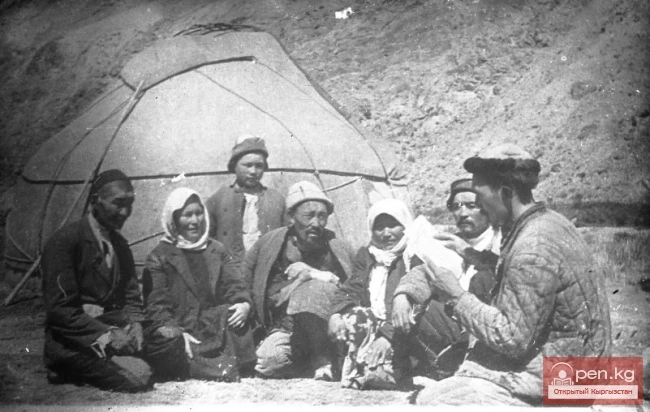

Pressure on Peasantry through Collectivization

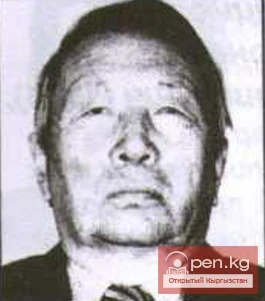

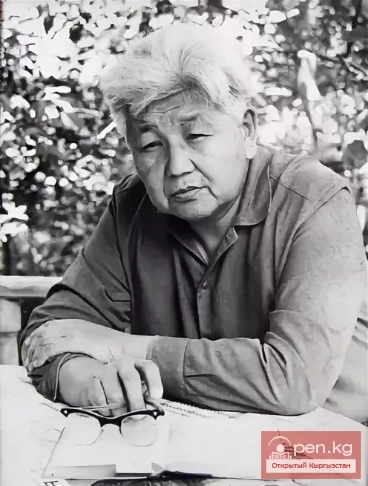

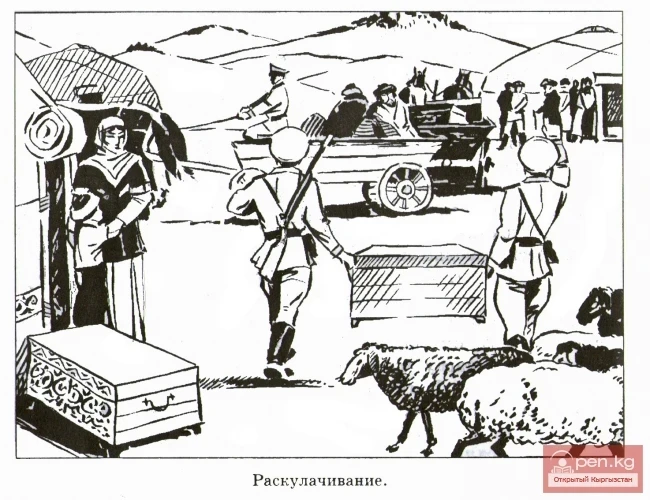

Y. Abdrakhmanov was a staunch opponent of administrative arbitrariness towards the peasantry. At the regional party conference in June 1930, when the negative consequences of collectivization "Stalin-style" became evident, especially in the outskirts of the country, in Kyrgyzstan, in the livestock zone, he said: "Cooperation is the highway to socialism... But how we have treated this highway, how we help

cooperation to truly become what it should be according to the definition of Vladimir Ilyich. In this regard, there are significant shortcomings; it is not strengthened by good Bolsheviks. As a result of underestimating cooperation as a transitional stage to collective farming, we set such paces for the creation of collective farms in some areas this year that led to a leapfrogging in our cooperative system.

The regional committee must especially emphasize the role of cooperation in the conditions of Kyrgyzstan and give a strict directive to shift the center of gravity in a number of regions of Kyrgyzstan towards the use of all the simplest forms of production cooperation for the transition from fragmented peasant farms.

Regarding the rough pressure on the peasantry to implement the Stalinist line of completing collectivization "by the autumn of 1931 or at the latest by the spring of 1932," he noted the following: "During my absence (while I was on a business trip), Kyrgyzstan experienced several unpleasant events: Issyk-Kul, Naryn, At-Bashi, Balakchi had something akin to Tambov (peasant uprisings). However, the explanation is that all this is the result of the intensification of class struggle. A strange theory gained citizenship — if the population organizes a rebellion, it means the line is correct."

Let us present some lesser-known facts reflecting his reaction to the curtailment of the NEP at the end of the 1920s, to the acceleration of production cooperation through administrative pressure methods, which, in his opinion, could only undermine the trust of the peasantry in Soviet power.

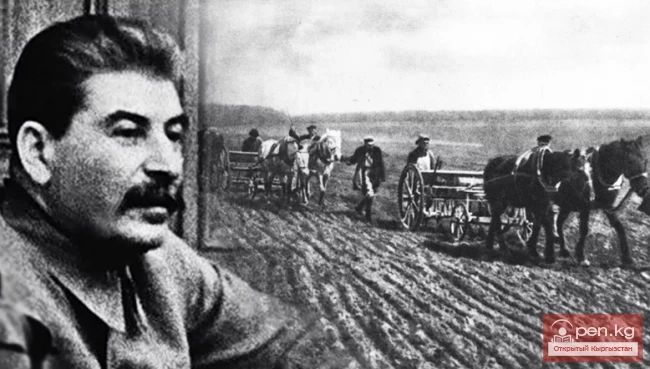

In the autumn of 1930, Stalin, Molotov, and Kaganovich sent the following telegram to the Central Asian Bureau of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) to Zelensky, Ikramov, and Bauman: "We consider your plan of 26 million poods (of cotton) for Central Asia completely unacceptable.

We believe that Central Asia must provide no less than 28 million poods. The remaining cotton should come from other regions of the USSR.

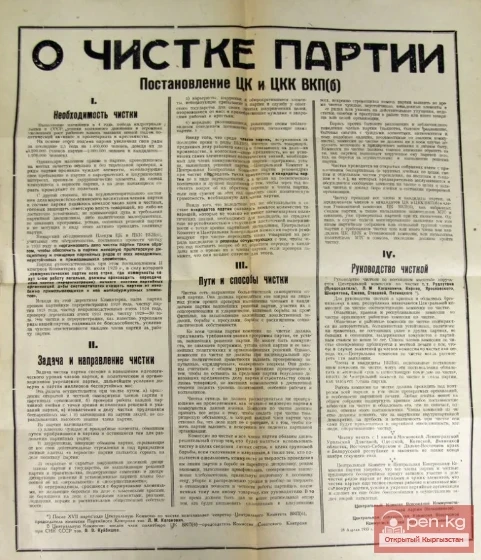

We insist that all measures be taken, including the mobilization of Komsomol members, party members, and non-party workers, to ensure the plan of 28 million poods is fulfilled. We propose to remove from their posts and expel all whiners and pessimists. Those who disrupt the plan should be excluded from the party."

The leadership of the Central Asian Bureau was put in a difficult position. The third cotton harvest was coming to an end. I. Zelensky, who undoubtedly understood to whom the words "expel the whiners and pessimists" referred, reported in a response telegram to I.V. Stalin on December 19, 1930, that his directive was being implemented. At the same time, he considered it necessary to inform that "the first and second harvests have been fully collected from the fields. A negligible amount remains in the fields from the third... Exceeding the plan beyond twenty-six and a half million poods may come at the expense of extracting cotton fiber that has settled with the population over the previous years and used for household needs, for robes and blankets, which may lead in some places to administration and excesses regarding the middle peasant..."

Abdrakhmanov's Approach to the Problems of Economic Construction in the Republic