A Turn in Social and Political Life. By the mid-1980s, a deep crisis had emerged in all spheres of public life in the USSR. Its international prestige had fallen. The existing administrative-command system of governance no longer corresponded to the conditions of the changing times.

In 1982, after the death of L. Brezhnev, Y. Andropov took the helm of the country. He made considerable efforts to correct the distortions and mistakes of the party-state management and to improve the situation in the country. He paid special attention to strengthening labor discipline. However, he could not complete his initiatives: he died in 1984. Power returned to a representative of the Brezhnev-era conservative leadership — K. Chernenko. As a result, everything reverted to its previous state.

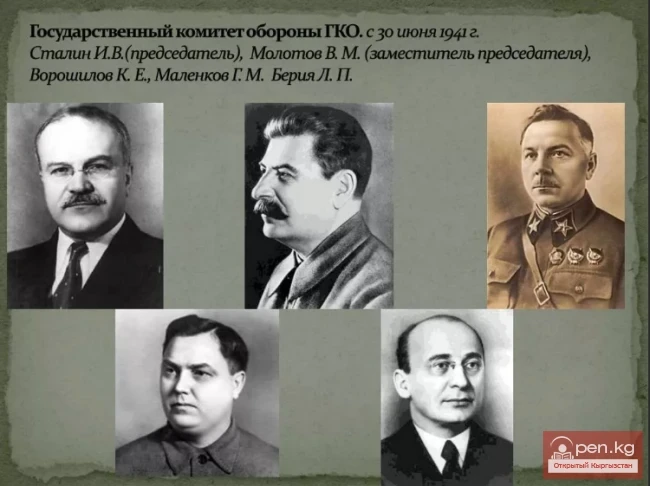

However, within the upper echelons of power, there was already a group of people who understood that radical changes were needed in the thinking and psychology, organization, style, and methods of work of both the party and the state apparatus, as well as the country’s leadership. In 1985, they took power into their own hands. Thus, the new leader of the country became M. Gorbachev.

To implement management reforms, personnel changes were made at all levels: several individuals particularly loyal to Brezhnev's policies were removed from their positions. They were replaced by people who built plans to lead the country out of the crisis based on new ideas and perspectives.

In 1985, the head of the Communist Party of the republic, T. Usubaliev, who had led Kyrgyzstan for a quarter of a century, was removed from his position, and A. Masaliev was elected in his place. The leaders of district and regional committees changed. Key positions in the party-state apparatus of the republic were occupied by individuals appointed by Moscow. Similar personnel changes occurred in other republics. The removal of D. Kunaev, who had led Kazakhstan for many years, and the appointment of G. Kolbin in his place led to national unrest in Almaty, which had tragic consequences. Force was used against the protesting youth.

The new leadership of the country proclaimed a new policy — the policy of perestroika and acceleration. Perestroika aimed to renew all aspects of social life, decisively overcome stagnation processes, and create conditions for accelerating the socio-economic development of the country.

Society began to move. People started to express their opinions more boldly and participate more actively in solving public problems. Glasnost intensified. The mass media began to respond more sharply and promptly to negative facts, highlighting the shortcomings of public life. Society saw how serious the mistakes made in socialist construction were. Opinions were expressed that the crisis of society was a result of the retreat from and violation of Leninist norms of party life, which needed to be restored, etc. Therefore, the 70th anniversary of the October Revolution in 1987 was held in an anti-Stalinist spirit. A course was set for building a humane, democratic socialism.

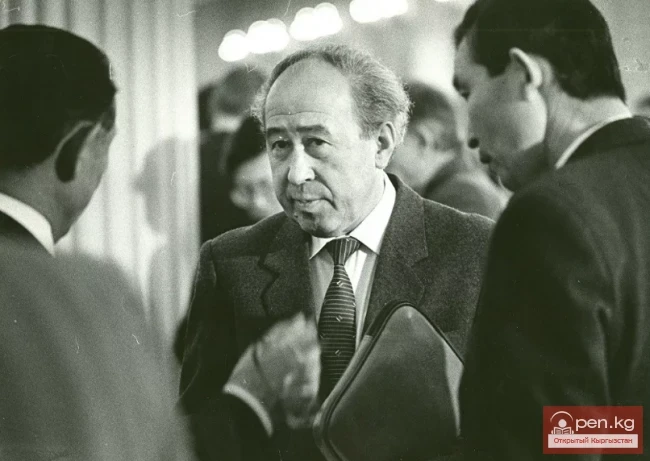

Democratic changes also occurred in Kyrgyzstan, with the creative intelligentsia led by C. Aitmatov becoming the herald of new transformations. The rehabilitation of those unjustly repressed in the past began. In 1989, Moldoo Kylch and Kasym Tynystanov were rehabilitated.

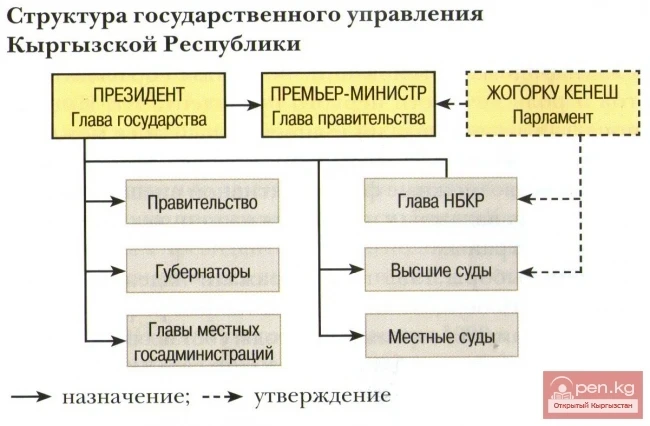

In 1989, amendments and additions were made to the Constitution (Fundamental Law) of the USSR aimed at improving the electoral system and the system of state governance. The highest body of power became the Congress of People's Deputies of the USSR.

The new election law introduced a new procedure for electing deputies. Now deputies were elected for five years. The number of candidates for deputies was not limited. They could be nominated at meetings at their place of work or residence.

New Elections. In February 1990, elections were held for the Supreme and local councils of the Kyrgyz SSR — the first democratic elections in Kyrgyzstan. In many electoral districts, several candidates for deputies were nominated. Democratic organizations also actively participated in the elections.

Democratic elections contributed to a qualitative change in the composition of the deputy corps. Many educated state figures who understood the needs and aspirations of the people entered it. The activity of local councils increased. Party organs could no longer impose their directives on them as they had before.

In April 1990, at the first session of the Supreme Council of the Kyrgyz SSR, Absamat Masaliev was elected Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Kyrgyz SSR and became the head of state.

In March 1990, an event of great historical significance for all citizens of the Union occurred: the III Congress of People's Deputies of the USSR abolished the article of the Constitution regarding the leading role of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In Kyrgyzstan, the supremacy of party organs was also abolished. Thus, a wide road was opened in the country to the main feature of a democratic society — multi-partyism.

Perestroika in the Economy. Perestroika in the economy began with a transition to new economic management methods. The conservatively inclined leadership of Kyrgyzstan approached the introduction of new economic mechanisms very cautiously. However, enterprises began to adopt methods such as full economic accountability, self-sufficiency, self-financing, and others in their operations. The provision of greater economic freedoms than before allowed enterprises and their workers to develop entrepreneurial skills, conduct elections for enterprise and farm leaders on an alternative basis within labor collectives.

However, on the other hand, the path for the existence of other forms of ownership — collective, cooperative, private, communal — besides state ownership was not opened. Without this, there could be no interest from workers and collectives in the results of labor. Without this, economic perestroika was impossible.

Transition of Agriculture to Market Relations. From 1986 to 1990, laws on land, lease, land ownership rights, and land use were adopted. Based on these, reforms in the agriculture of the republic were to be conducted.

Thus, conditions were created for the operation alongside kolkhozes and sovkhozes of new forms of management, such as peasant farms, rental and cooperative enterprises, as well as brigades applying methods of economic accountability and self-financing. Competition in production and sales of products increased.

As a result of the reforms, the economic situation of kolkhozes and sovkhozes improved somewhat. From 1986 to 1989, their incomes increased by 47 percent, and labor efficiency improved. Most importantly, the population of the republic was sufficiently provided with food.

In 1990, Kyrgyzstan had over 1 million head of cattle, about 10 million sheep and goats, 400 thousand pigs, more than 300 thousand horses, and 14 million chickens. However, the increase in livestock numbers worsened the condition of pastures, some of which became unsuitable for grazing. In the pursuit of quantity, the quality of agricultural products was neglected, leading to increased production costs.

To rectify the situation in agriculture, it was decided in 1986-1990 to double the purchase prices for products produced beyond the state plan. Farms were allowed to keep and sell one-third of the produced products freely. In addition, rural residents were given the right to create independent family farms.

In 1993, a law on cooperation was adopted, creating a legal framework for those wishing to organize their own farms. The first peasant and farmer households began to emerge.

Initially, only the most initiative individuals took up the creation of peasant farms. They received fertile lands, equipment, and preferential long-term loans for rent. As of January 1, 1991, 4,500 peasant and farmer households had been established in the republic. On average, each household had 2 cows, more than 140 sheep and goats, and 3 horses.

Nevertheless, the people, having become unaccustomed to independence and initiative over the years of the administrative management system, were slow to organize their own farms, while the chairmen of kolkhozes, in turn, sought to prevent the fragmentation of their farms. The process of economic transformation in the countryside was very slow. In the conditions of the prevailing dominance of the planned socialist system of management, neither the cooperative movement nor peasant and farmer households could develop successfully.