The Institute of the Presidency in the Kyrgyz Republic

Since 1991, the institute of the presidency has gained significant authority in the Kyrgyz Republic. In modern Kyrgyzstan, it is one of the key components in the system of state power. Its rational structure and functioning are important conditions for ensuring constitutionalism in the state.

In the early years of independence, a presidential-parliamentary governance system emerged based on the Constitution of the KR of 1993. It gradually drifted towards strengthening presidential power through constitutional amendments and additions made during referendums (1994, 1996, 1998).

The institute of the presidency in the Kyrgyz Republic was established before gaining independence. As early as 1990, the country's parliament, represented by the Supreme Council of the Kyrgyz SSR, elected the first president of the country.

The establishment of the institute of the presidency in Kyrgyzstan, as in other Central Asian republics on the brink of the disintegration of the USSR, was a logical step in the political development of the country. Firstly, it marked the end of the stage of a one-party political system of the Soviet type, where the party nomenclature exercised both direct and indirect control over the executive, judicial, and legislative branches of power.

Secondly, the introduction of the institute of the presidency initiated the process of popular voting and the election of leaders in Central Asia. And thirdly, the institute of the presidency filled a peculiar political and ideological vacuum that emerged during the transitional phase — the Communist Party lost its dominant positions in the political, ideological, and social spheres, while new political parties and institutions had not yet been formed.

In October 1991, the first nationwide elections took place. They legitimized and confirmed the president of independent Kyrgyzstan. This tradition of direct presidential elections replaced the process of electing the president through parliament and later became enshrined on a permanent constitutional basis.

The transformation of the country into the Kyrgyz Republic occurred more or less democratically, avoiding various clashes and open conflicts between opposing sides. This process in other CIS countries (Azerbaijan, Moldova, Georgia, Tajikistan) was much harsher, sometimes escalating into bloody confrontations.

The established structure of presidential power in Kyrgyzstan responded to the situation of real threats and risks of development that arose with the country's unexpectedly gained independence:

• The republic did not have equipped state borders and an established system of contractual and national security, making it open to all forms of expansion, including economic pressure from countries through stable currency;

• The country lacked its own sources of fuel, gas, and means for profitable exploitation of mineral deposits;

• The division of the country by mountain ranges fostered economic regional and clan disunity, fragmenting public life;

• Objective processes were complicated by the immaturity of civil society, underdevelopment of a democratic tolerant political culture, weakness of the legal framework, and, most importantly, periodically escalating processes of property redistribution during privatization and the introduction of private land ownership;

• There remained a threat of external and internal expansion by organized groups of internal and external crime, formed on the basis of drug trafficking, religious extremism, and international terrorism;

• There were potential dangers of interethnic conflicts erupting in a multinational and multi-confessional country;

• A central threat to state governance emerged — the dualism of development (the existence of two directions of development — state independence and national statehood with the possibility of declaring two goals — national and popular).

For these and other reasons, the evolution of the institute of the presidency in the country shows signs of several basic models:

• Signs of pure presidential power (American model): the president is the head of the executive power, the supreme commander-in-chief, and the head of international relations; he receives a mandate to govern from all citizens, not from parliament;

• Signs of centralization (Asian model): the president performs the functions of head of state and head of government, parliament can be dissolved at the president's discretion, the president appoints the prime minister and can dismiss any minister;

• Signs of presidential-parliamentary power (Euro-French model): the president is the head of state but not the head of government; he has the right to approve resolutions adopted by the government and can return them for reconsideration in case of disagreement; the president has the right to "veto" laws passed by parliament and supported by the government; under certain circumstances, he can dissolve parliament and call new elections, declare a state of emergency, and hold a nationwide referendum.

In the Kyrgyz model of presidential governance, there are differences from the French and generally from the European approach.

There, the president is the head of government, while the government itself is accountable not to the president but to parliament. This means that in a semi-presidential form of governance, there is a potential conflict both between the president and parliament and between the president and the prime minister.

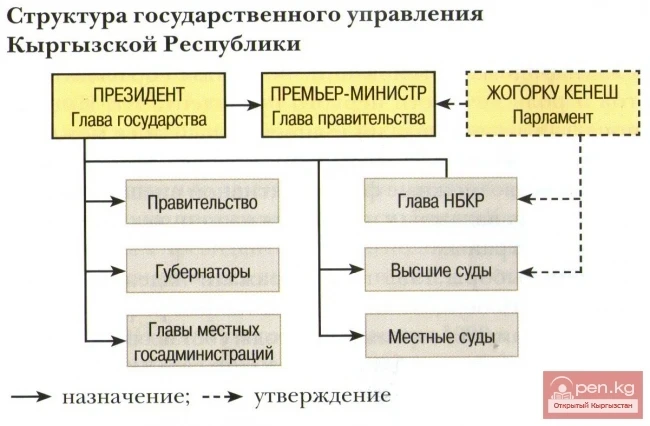

These possible contradictions are taken into account in the Constitution of the KR (1993). The president is empowered to appoint the prime minister (with the consent of parliament) and members of the government. The structure of the government is determined not by parliament but ultimately by the president. The president controls the work of the government and has the right to preside over its meetings. The president appoints heads of territorial state administrations, dismisses them, forms and heads the Security Council, determines the main directions of foreign policy, and takes measures to ensure the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country. The president is the supreme commander of the armed forces of the country, appoints, with the consent of parliament, a number of key positions in the republic — the attorney general, the chairman of the National Bank, and presents candidates to parliament for the positions of chairman of the Constitutional Court, chairman of the Supreme Court, and chairman of the Arbitration Court of the Kyrgyz Republic.

As for relations with parliament, the Constitution of the KR endowed the president with some legislative powers. The president submits bills to the Jogorku Kenesh, signs laws or returns them for revision, issues decrees and orders that have the force of law in the given territory.

The emerging presidential-parliamentary form of governance initially leaned heavily towards a predominantly presidential model. A number of experts on new independent states refer to this model as mixed.

For it, according to experts, is characterized by a certain reduction in the role of government and parliament; a centralization similar to that of the first secretaries of the Central Committees of the Communist Parties in the new structures of state governance.

The diminishing significance of corporate forms of governance reduced the president's accountability for the results of governing the country.

A noticeable desire to strengthen presidential power was intensified by adherence to certain historical traditions and the inertia of political culture. This is particularly evident in the establishment of the administrative powers of the president's administration, which, while formally an auxiliary body for the president, effectively exercised comprehensive control functions over the government.

The president's administration, not being a constitutional body, was less transparent compared to the government. Formally, it assisted the president in carrying out his functions, but in practice, without accountability, it held tools of personnel policy, control over the government and regional power (according to the "On the Administration of the President of the KR" from July 8, 1994), often ensuring the economic and administrative functioning of both parliament and government.

The centralization of power was formally dictated by the objective necessity to overcome the threats and risks of the transitional period to market relations, striving to make this period less painful for the population. In fact, it led to management failures. The greatest negative effect was caused by the growing corruption. According to the Accounts Chamber of the KR, the officially recognized damage to the state from corruption for 1997 and 1998 amounted to over one billion soms per year.