Animal Husbandry in the 20th - Early 21st Century

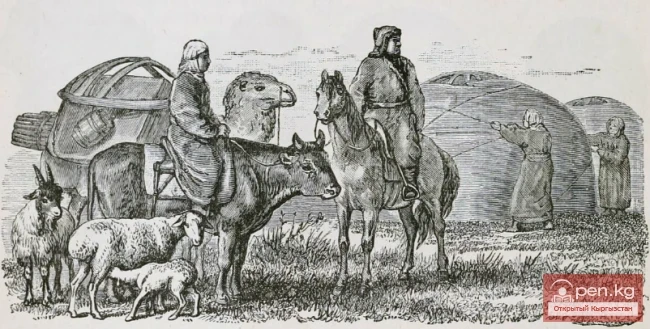

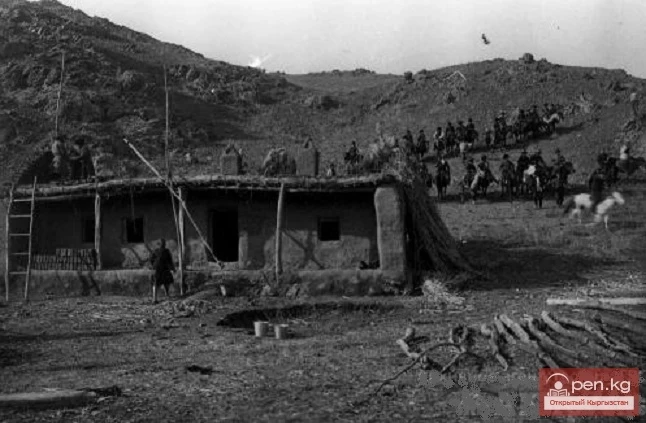

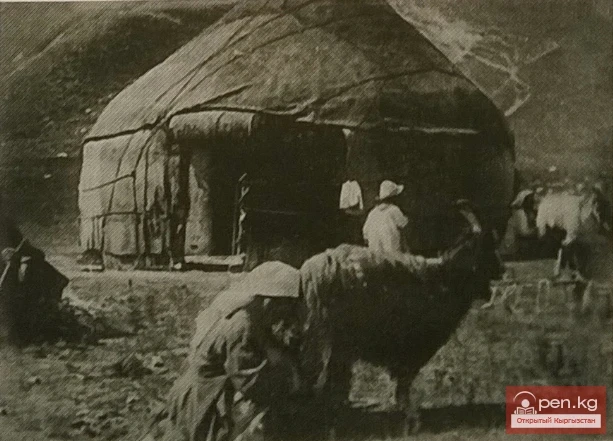

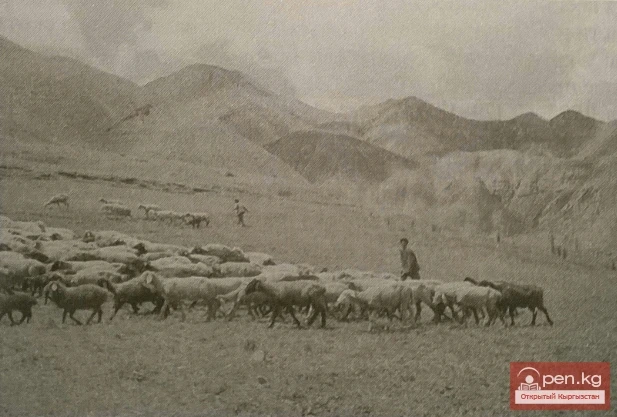

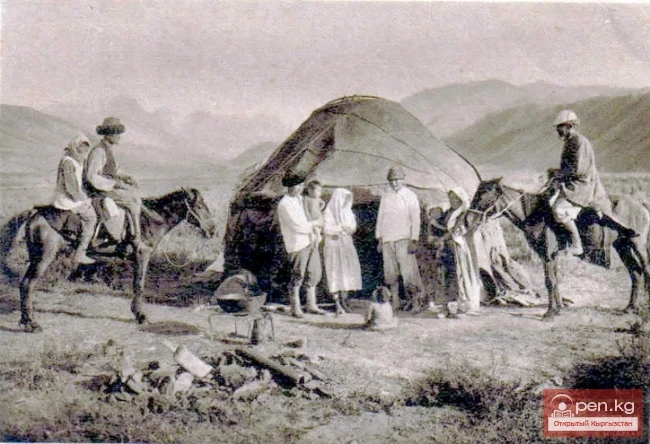

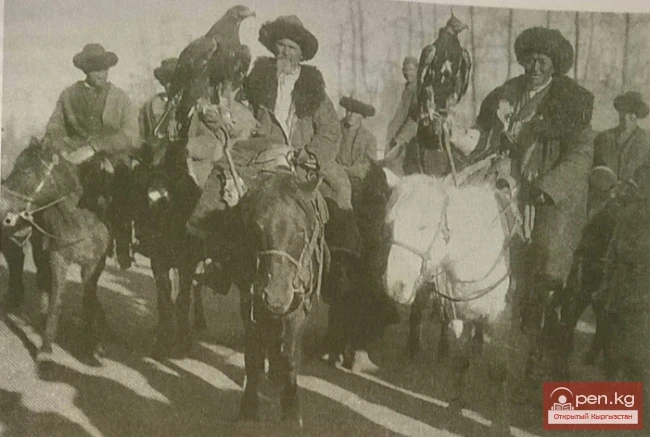

By the beginning of the 20th century, animal husbandry continued to be the leading sector of the economy among the Kyrgyz. According to various sources, the number of settled households by 1914-1916 ranged from 15 to 30% in the Pishpek, Przhevalsk, and Namangan districts (in particular, in the Talas Valley, their share was especially small in the adjacent mountainous areas, as well as in the high-altitude southern regions (Dzhamgerchinov, 1963, p. 49). In the Osh, Margilan (Skobelev), and Kokand districts, semi-nomadic herders made up 65% of the total population, while in the Andijan district - more than 50% (History of the Kyrgyz SSR, 1986, pp. 114, 115). By 1914, 22.4% of the Kyrgyz led a completely settled lifestyle {Tursunbaev, 1934).

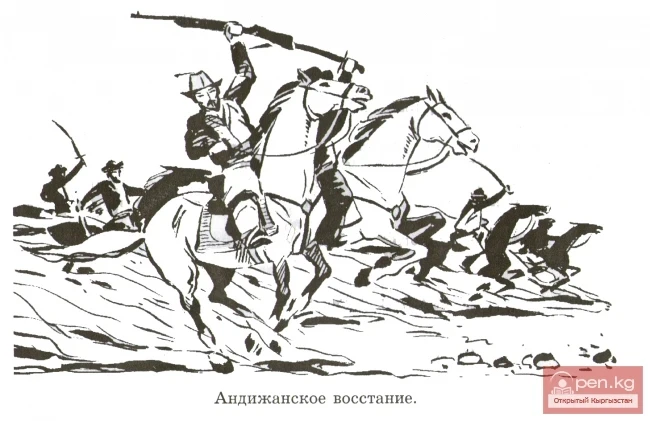

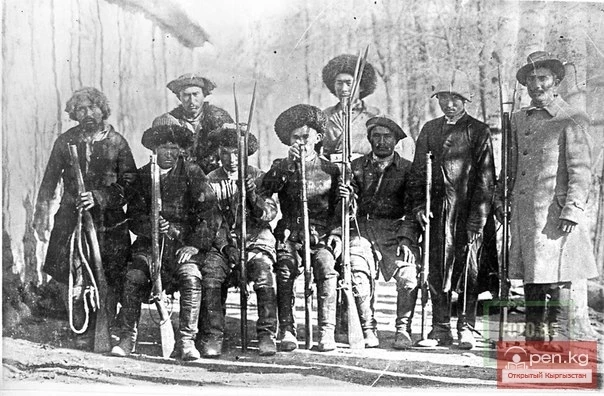

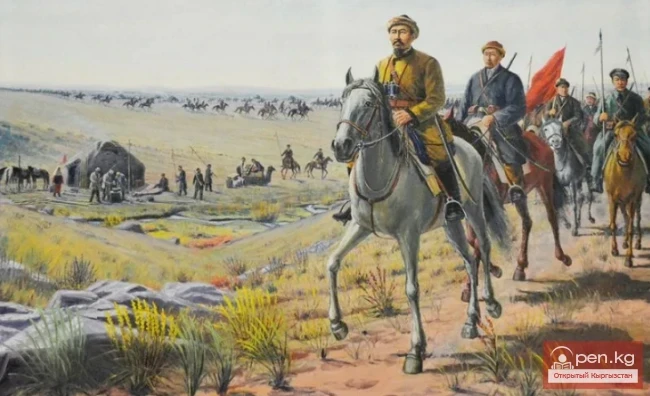

The violent measures undertaken in the first decades of Soviet power, related to the transition to new forms of economy, the collectivization of livestock and means of production, sedentarization, and the policy of collectivization and dispossession provoked protests among the population. Small terrorist acts were organized against officials, and people slaughtered livestock en masse, unwilling to hand it over to the collective farms, fleeing beyond the republic.

Despite the difficulties associated with breaking the traditional way of life, the consequences for the Kyrgyz, due to their higher share of sedentariness, turned out to be less tragic than in neighboring Kazakhstan.

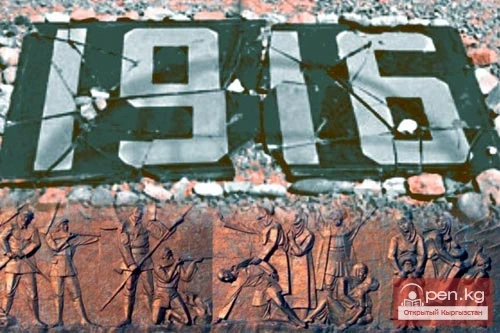

The tragic events of 1916-1934 - the uprising of 1916, the Civil War, collectivization - led to a significant reduction in livestock in the republic (from 1913 to 1934, from 4.2 million heads to 1.6 million (Altyshbaev, 1959, pp. 49-51; Domestic Animals... Vol. 2, p. 29). This circumstance had a favorable consequence - for some time, ecological problems associated with excessive pressure on pastures, which had occurred in the previous period, were alleviated.

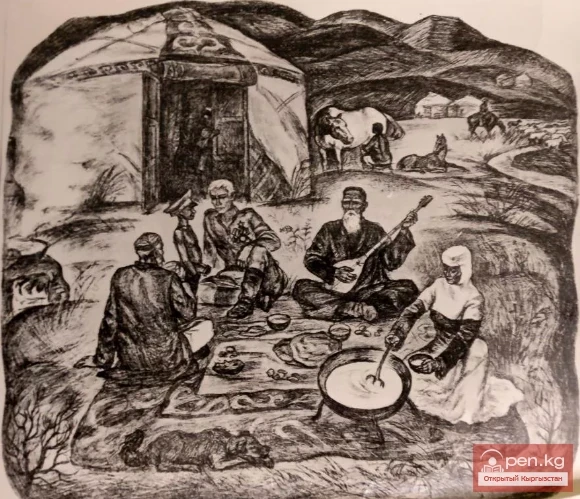

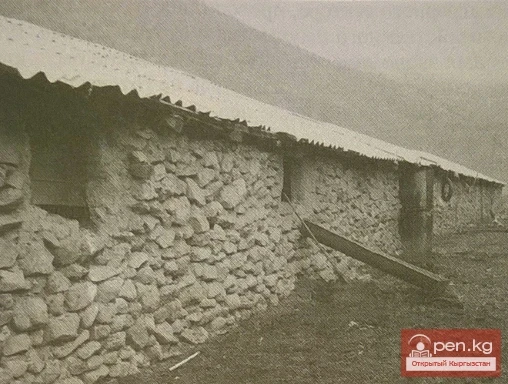

Herders went through the school of collective farming within the framework of TOZ (artels), which were later transformed into collective and state farms. Thanks to state material and financial support, the infrastructure of the livestock sector was created, which was given great importance within the framework of the economic division of labor in the USSR. Roads were built to remote summer pastures, electricity was brought to wintering sites, technically equipped livestock complexes were constructed - sheep commodity farms (OTF), dairy commodity farms (MTF), shearing points, and others, centralized processing and marketing of livestock products were organized. At the same time, state ideology provided for the creation of a prestigious image of the professions of shepherd, horse herder, and milkmaid.

The Soviet economic system, on a planned basis, did not foresee any significant entrepreneurial initiative from collective and state farm workers, which fostered paternalistic attitudes.

At the same time, the share of the private sector decreased.

A significant blow to traditional animal husbandry was dealt during the rule of N. S. Khrushchev, in the period of struggle against the personal subsidiary farms of collective farmers. Previously, Kazakh and Kyrgyz collective farmers were allowed to keep up to 100 sheep, 8-10 heads of cattle, and horses, and 3-5 camels for personal use (Baibulatov, 1969, p. 98), but from the early 1960s, it was prohibited to have more than 10 sheep and one cow, or instead a horse; this ban remained in effect until 1988. Since the overwhelming majority of the rural population preferred to have a cow, the share of horses sharply decreased: while the number of sheep increased fourfold overall from 1940 to 1985 (for private farmers - just over twofold), and cattle - doubled (for private farmers - by 15%), the number of horses not only did not increase but decreased by 1.5 times (for private farmers - by about 25-30%). By 1985, the situation had somewhat improved compared to the period of "second collectivization" in the early 1960s, when the number of private sheep decreased by 1.7 times compared to 1940, horses - by almost 5 times, and cattle - by 1.5 times (People's Economy, 1987, p. 103), however, the disproportion with too small a number of horses was not corrected by the end of the Soviet period.

The consolidation of collective farms in the 1960s-1970s also had negative consequences. Back in the 1930s, the optimal size of a Kyrgyz collective farm was determined to be 50-100 households (Belousov, 1935, p. 42), however, even then the average sizes of collective farms varied from 63 households in the Frunze canton to 197 in the Naryn region (History, 1989, pp. 216, 217; Kushner, 1929, p. 16), in the 1960s the average size of a collective farm was 542 households, and in the 1970s - 710 households (Sitnyansky, 1998, p. 104).

Far from always did the rational organization of animal husbandry give rise to serious ecological problems.

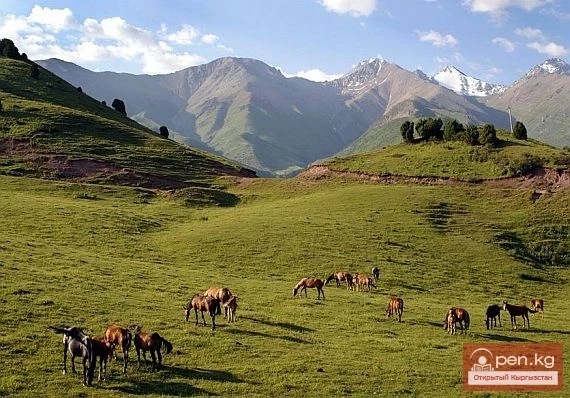

Excessive pressure on natural resources due to the unrestrained increase in livestock (by the late 1980s, according to official data - 10-11 million, and in fact - up to 13-14 million sheep alone) led to the degradation of pastures, including high-altitude alpine zones. More than 1.3 million hectares were overgrown with non-feed plants and bushy, 1.7 million hectares were degraded, of which 170 thousand hectares were in a severe state (Dzholdoshev, 1997, pp. 168, 169; Klyashtorny, 1999, p. 7). According to Kyrgyz specialists' opinions expressed in the early 1990s, if such pressure on pastures continued, there was a threat of irreversible degradation within the next 5-15 years (PM G. Yu. Sitnyansky, early 1990s).

By the time of the collapse of the USSR, the livestock sector was already beginning to enter a crisis. In accordance with the policy of independent Kyrgyzstan aimed at reforming the agricultural sector, the denationalization and privatization of agricultural property and livestock were carried out (Jumaev, 1997; Jacquesson, 2003).

However, the overall economic situation in the country was extremely difficult. Former members of collective and state farms were not prepared to maintain privatized livestock without losses.

Due to insufficient feed, lack of proper zootechnical and veterinary care with the use of medicines and vaccinations, and poor-quality pastures, there was a mass die-off of livestock. The number of sheep, for example, decreased from 10-11 million to 4 million (according to unofficial data, in the 1990s there were periods when it fell to 1 million).

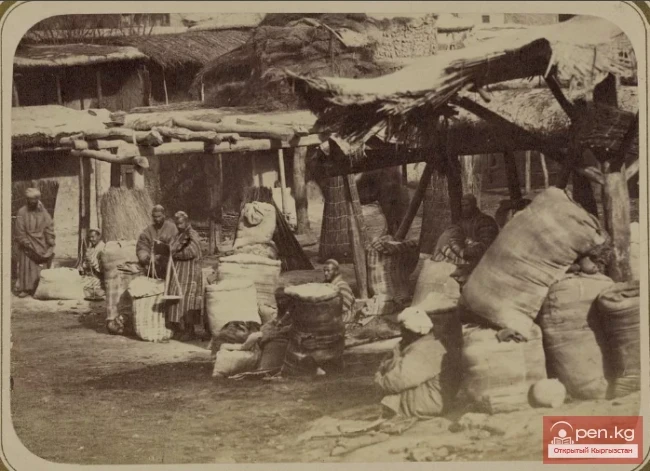

The purchasing power of rural residents was very low. The value of livestock depreciated, which for several years became a unit of trade exchange. Small cooperatives, farms, and peasant households exchanged livestock for spare parts for agricultural machinery, fuel, and lubricants. In families, it became common to acquire food, clothing, and everyday goods through barter transactions, with the livestock owner typically at a disadvantage. This economic situation negatively affected the development of animal husbandry, and the prestige of the profession steadily declined. Many hereditary herders sought new ways to earn a living, and the number of people moving to cities, especially en masse to the capital, Bishkek, increased.

The decline in livestock numbers in the 1990s once again, after 1916-1934, alleviated the urgency of the ecological problem, reducing the pressure on pasture lands. Currently, livestock numbers are growing again, and this circumstance necessitates the intensification of traditional animal husbandry.

Some Kyrgyz herders, despite economic difficulties, showed persistence, were not afraid to take risks, developed their production, and achieved certain results (Naumova, 2004; Naumova, Sagnaeva, 2006). Villagers, well aware of the natural and climatic conditions and the basics of animal husbandry, managed to increase their herd size and accumulate material resources. Modern herders use both traditional experience and modern knowledge. Despite the loss of some traditional skills in livestock breeding (Sitnyansky, 1997, pp. 76-89), the current generation of rural residents strives to continue the work of their fathers and grandfathers. Today, animal husbandry remains an important area of economic activity for the Kyrgyz and one of their sources of income.

Agriculture